Sunken Secrets In The Nile Delta

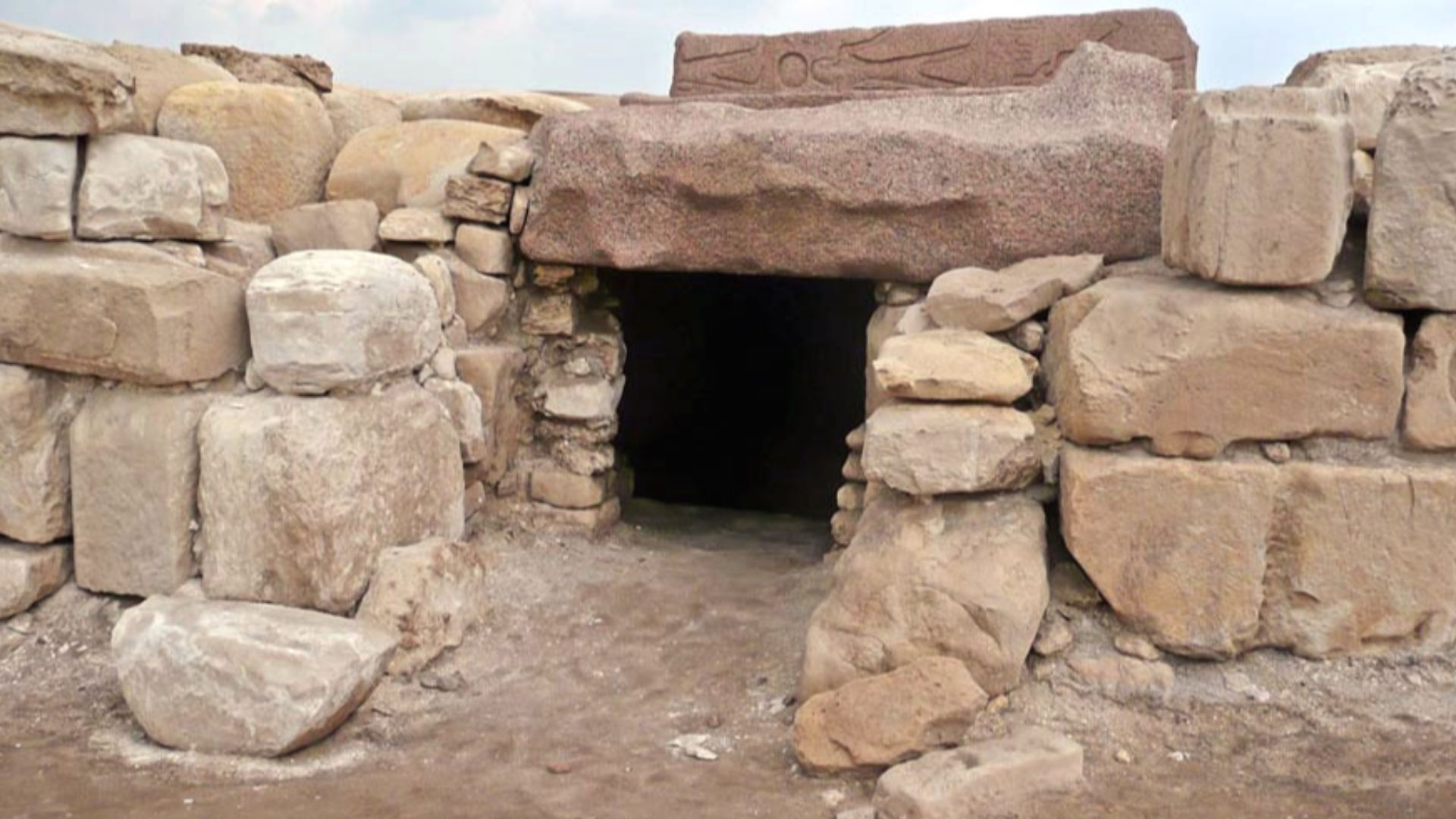

In the sprawling deserts of northern Egypt, where the sun bleaches ancient stone and the Nile’s old branches once flowed, there’s a city of secrets buried beneath millennia of sand. Tanis, once a powerful Delta capital, has long fascinated archaeologists. Its royal necropolis yielded treasures nearly as famous as those from the Valley of the Kings, but a new discovery has flipped ancient burial customs on their head—and possibly revealed a royal cover-up.

The Tomb That Didn’t Add Up

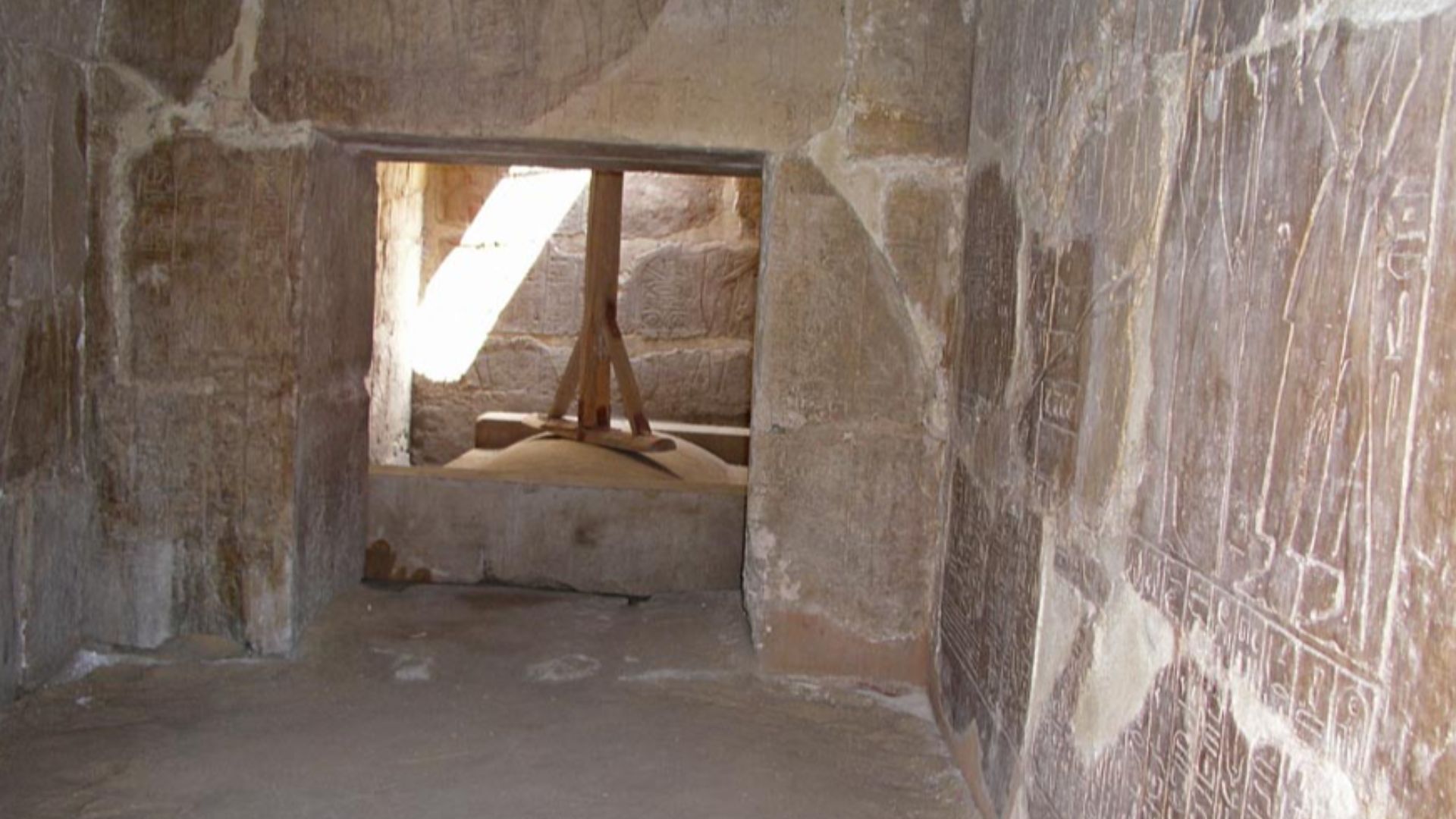

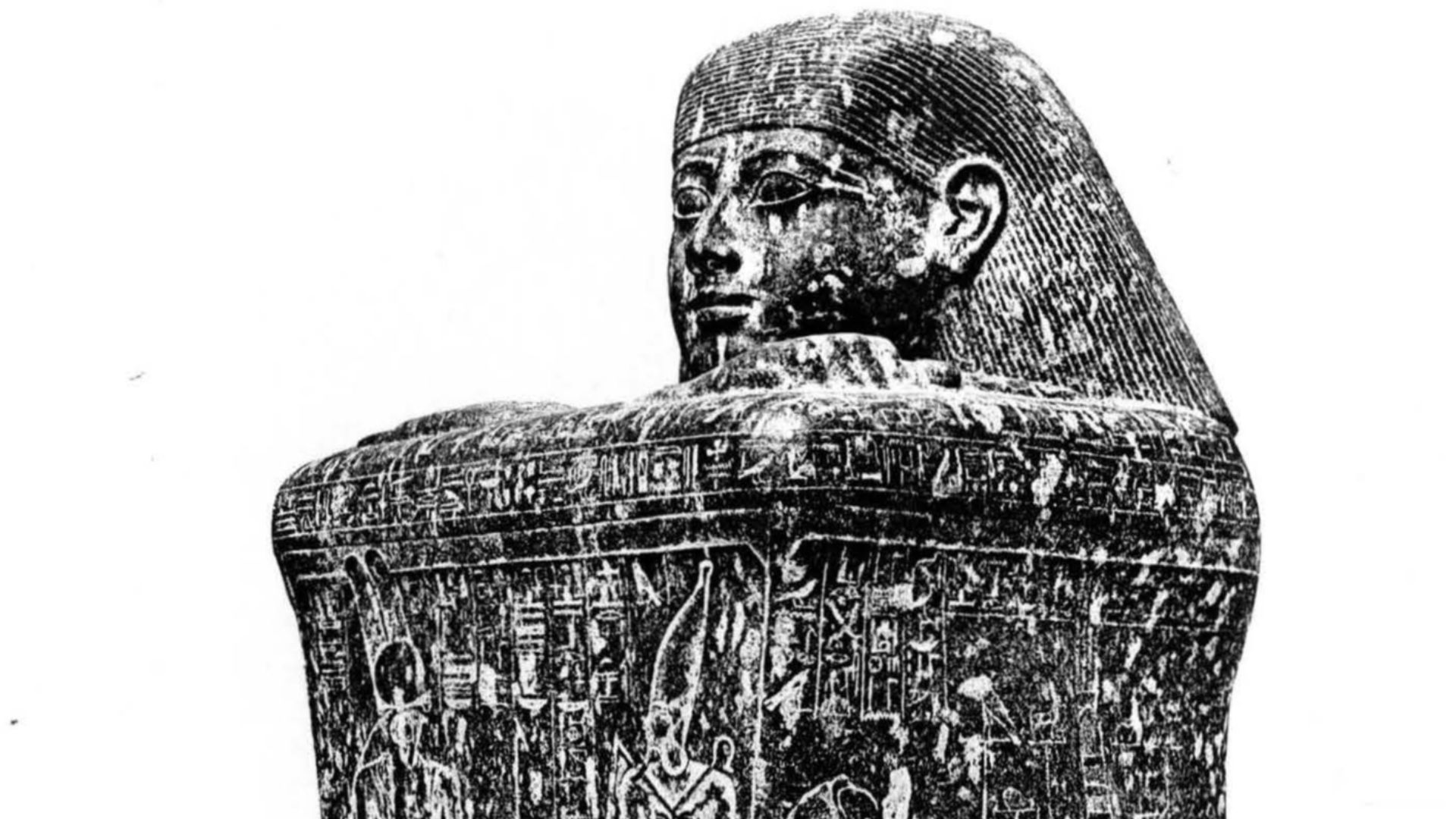

For decades, researchers knew about a large granite sarcophagus lying deep inside the royal tomb of Pharaoh Osorkon II, a ruler from Egypt’s 22nd Dynasty. But the sarcophagus was uninscribed and the chamber seemed oddly empty of expected funerary goods. That is, until recent cleaning and conservation work uncovered something extraordinary.

Osorkon_IIa.jpg: Jon Bodsworth derivative work: JMCC1 (talk), Wikimedia Commons

Osorkon_IIa.jpg: Jon Bodsworth derivative work: JMCC1 (talk), Wikimedia Commons

Ushabti Figurines With A Story To Tell

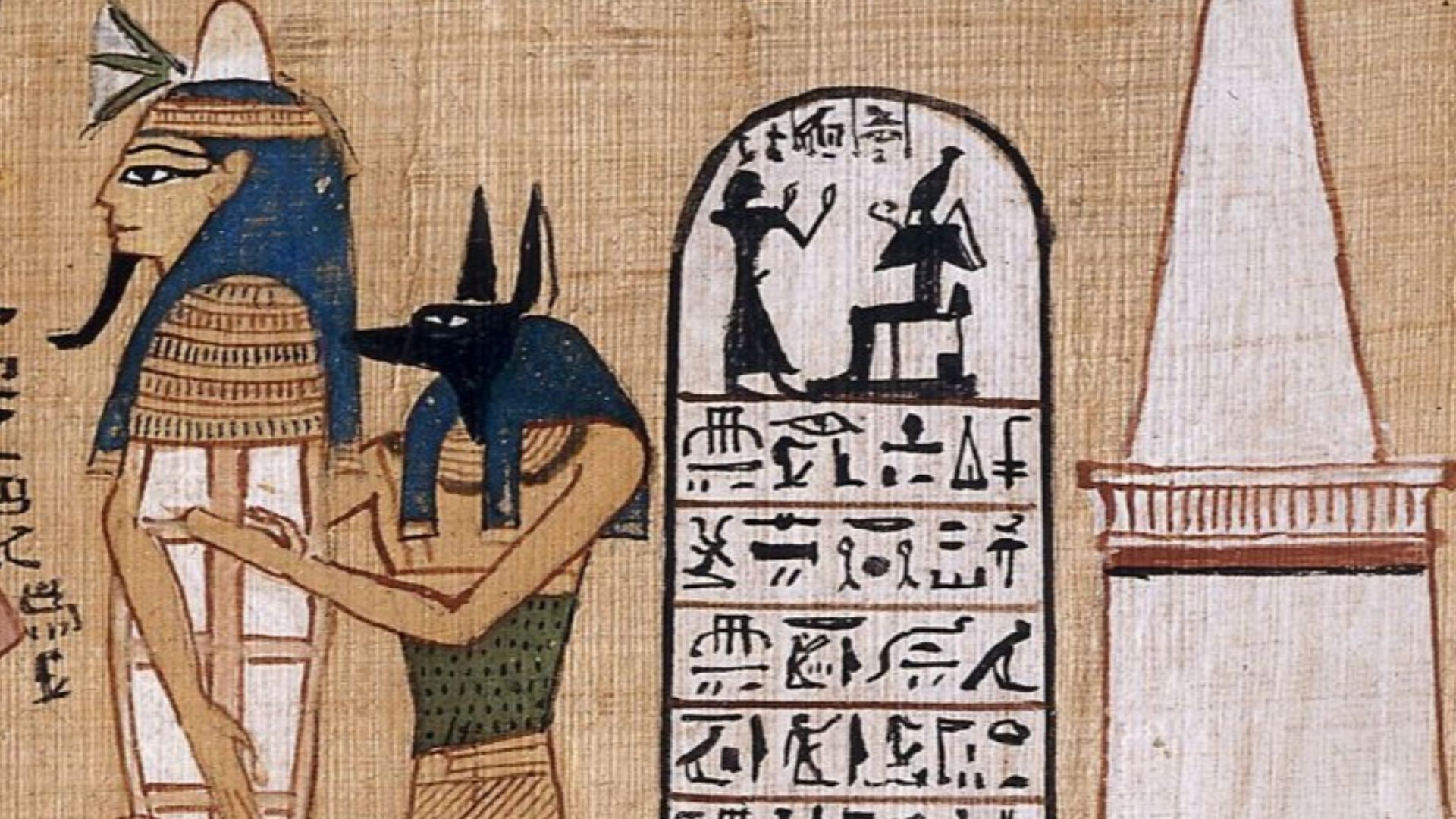

During a French-Egyptian archaeological mission’s cleanup of Osorkon II’s northern burial chamber, workers uncovered 225 ushabti figurines. The figurines were seen as small faience servants meant to accompany a pharaoh into the afterlife. These weren’t ordinary figures. Each one bore inscriptions identifying them as the funerary servants of Pharaoh Shoshenq III, another king who reigned decades after Osorkon II.

What On Earth Were These Figurines Doing Here?

Finding Shoshenq III’s ushabtis among the burial goods was a shock. Ushabtis were typically dedicated only to the tomb’s owner, so their clear association with Shoshenq III—and their original placement directly beside that unmarked sarcophagus—suggested something unusual was afoot.

Juan R. Lazaro, Wikimedia Commons

Juan R. Lazaro, Wikimedia Commons

A Pharaoh Out Of Place

Egyptologists had long puzzled over the anonymous sarcophagus inside Osorkon II’s tomb. Now it seems that the coffin, and by extension the burial, may actually belong to Shoshenq III, not Osorkon II. In other words, a pharaoh might be buried in a tomb built for another, centuries apart.

Exclusive to The Times, Wikimedia Commons

Exclusive to The Times, Wikimedia Commons

Shoshenq III: A Long Reign With Troubled Times

Shoshenq III ruled Egypt from around 830 to 791 BCE, a long reign marked by internal strife and political instability during the Third Intermediate Period. This was a time when Egypt was not a unified kingdom but an array of power centers often competing for control.

me ... hesham farouk ragab, Wikimedia Commons

me ... hesham farouk ragab, Wikimedia Commons

Osorkon II: The Predecessor With A Grand Tomb

Osorkon II, who reigned earlier in the same dynasty, had built a magnificent tomb for himself at Tanis, one whose riches and scale were considerable even after ancient looting. But if Osorkon II’s tomb was so splendid, why would Shoshenq III end up buried there?

Unknown authorUnknown author , Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author , Wikimedia Commons

A Case Of Royal Reuse Or A Cover-Up?

In ancient Egypt, reuse of tombs and burial goods was not unheard of, especially during periods of political change or crisis when resources were strained or priorities shifted. However, archaeologists suggest that what happened at Tanis goes beyond simple reuse.

Einsamer Schütze, Wikimedia Commons

Einsamer Schütze, Wikimedia Commons

The Cover-Up Hypothesis

Some researchers think Shoshenq III was intentionally buried in Osorkon II’s tomb as a political decision. Why? It could be tied to succession disputes, regional conflicts, or a desire by later rulers to associate themselves with an esteemed predecessor. But explanations vary, and the full story is still tangled in ancient power plays.

Jon Bodsworth, Wikimedia Commons

Jon Bodsworth, Wikimedia Commons

Shoshenq IV’s Shadow

Another intriguing idea involves Shoshenq IV, a successor who may have come to power after Shoshenq III. Some artifacts from the period bear Shoshenq IV’s name, and it’s possible that he claimed Shoshenq III’s original tomb, leaving the deceased king’s ushabti and burial goods in Osorkon II’s tomb to protect them from looters or to repurpose the grander burial for his own.

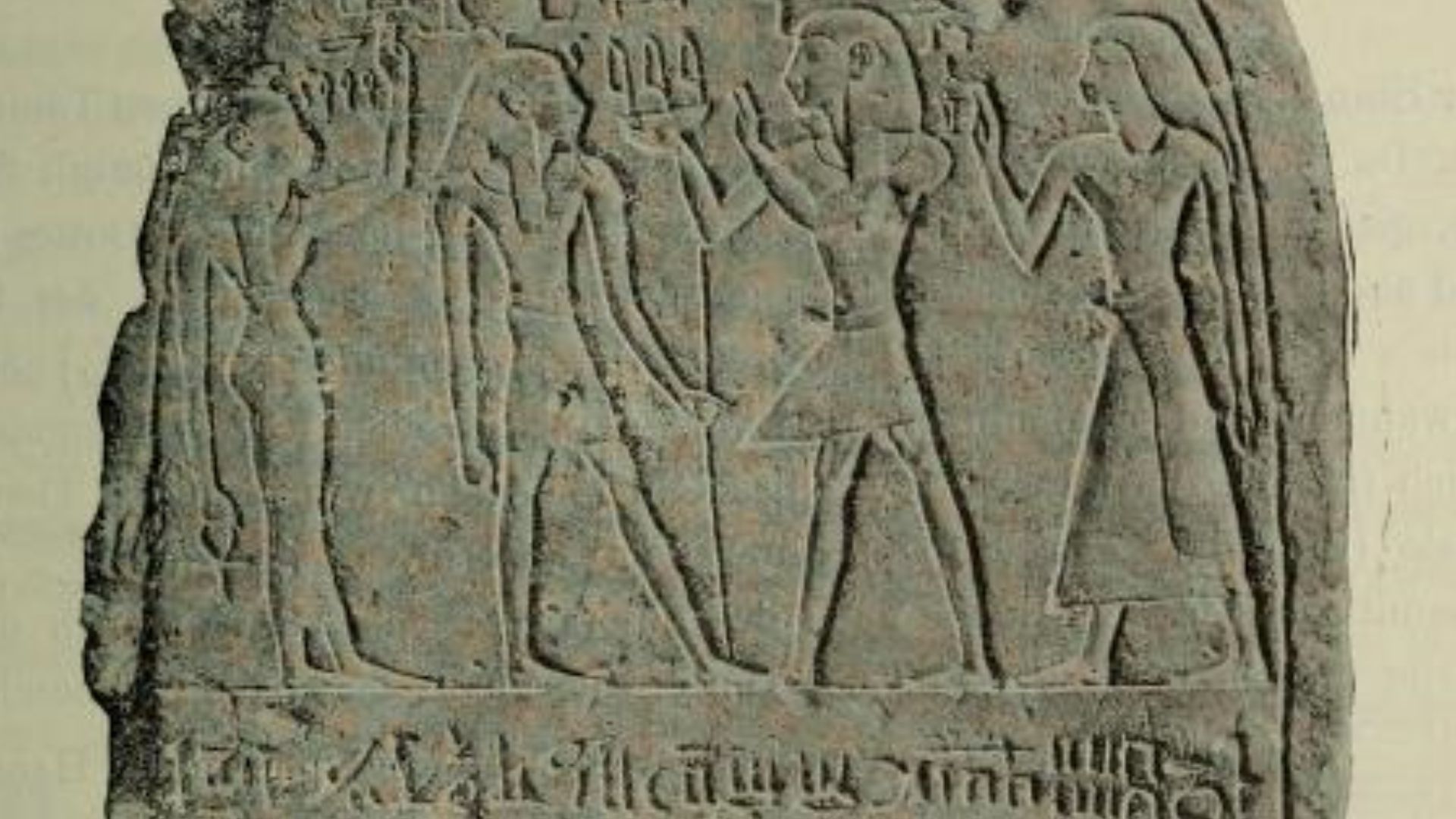

Georges Legrain (1865-1917), Wikimedia Commons

Georges Legrain (1865-1917), Wikimedia Commons

Tomb Robbers, Politics, And Protection

Tomb robbery was a constant threat in ancient Egypt, so moving a burial’s contents to a more secure location wouldn’t have been unprecedented. But moving a pharaoh’s burial from his own tomb into another king’s? Now that’s a dramatic twist. The silted context of the ushabti suggests they had not been disturbed since burial, adding weight to the idea that the shift happened long ago rather than recently.

Thayne Tuason, Wikimedia Commons

Thayne Tuason, Wikimedia Commons

The Significance Of The Ushabti Context

The fact that hundreds of ushabti were found carefully placed beside the sarcophagus, rather than scattered or looted, suggests this was an intentional placement. It wasn’t random or accidental debris. Their position reinforces the idea that Shoshenq III’s burial was considered legitimate, even if unusual.

Serge Ottaviani, Wikimedia Commons

Serge Ottaviani, Wikimedia Commons

A Tomb Cloaked In Silence For Decades

The sarcophagus itself had remained a mystery for years because it carried no inscriptions identifying its owner. Thanks to the ushabti discovery, that silence has been broken—and it tells a story of identity, power, and possibly crisis.

Jon Bodsworth, Wikimedia Commons

Jon Bodsworth, Wikimedia Commons

Rethinking Royal Burial Practices

This unusual case challenges long-held assumptions about Egyptian burial practice. Traditionally, pharaohs were entombed in monuments bearing their names, titles, and iconography. But if a king could be buried in someone else’s tomb for reasons other than robbery, it points to political, religious, or dynastic strategies we are only beginning to understand.

Tanis: A City Of Dynastic Drama

Tanis was the capital of Egypt during the 21st and 22nd Dynasties, periods of weakened central power and fragmented rule. Multiple rulers often held sway over different regions simultaneously, and shifts in leadership could lead to unconventional burial arrangements like this one.

Original uploader was Markh at en.wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

Original uploader was Markh at en.wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

Could Shoshenq III Have Been Buried Intentionally Here?

Some scholars argue that Shoshenq III might have been buried directly in Osorkon II’s tomb as a deliberate dynastic strategy, perhaps to invoke Osorkon’s legacy, authority, or religious favor. In eras of uncertainty, aligning oneself with powerful predecessors could have strong political value.

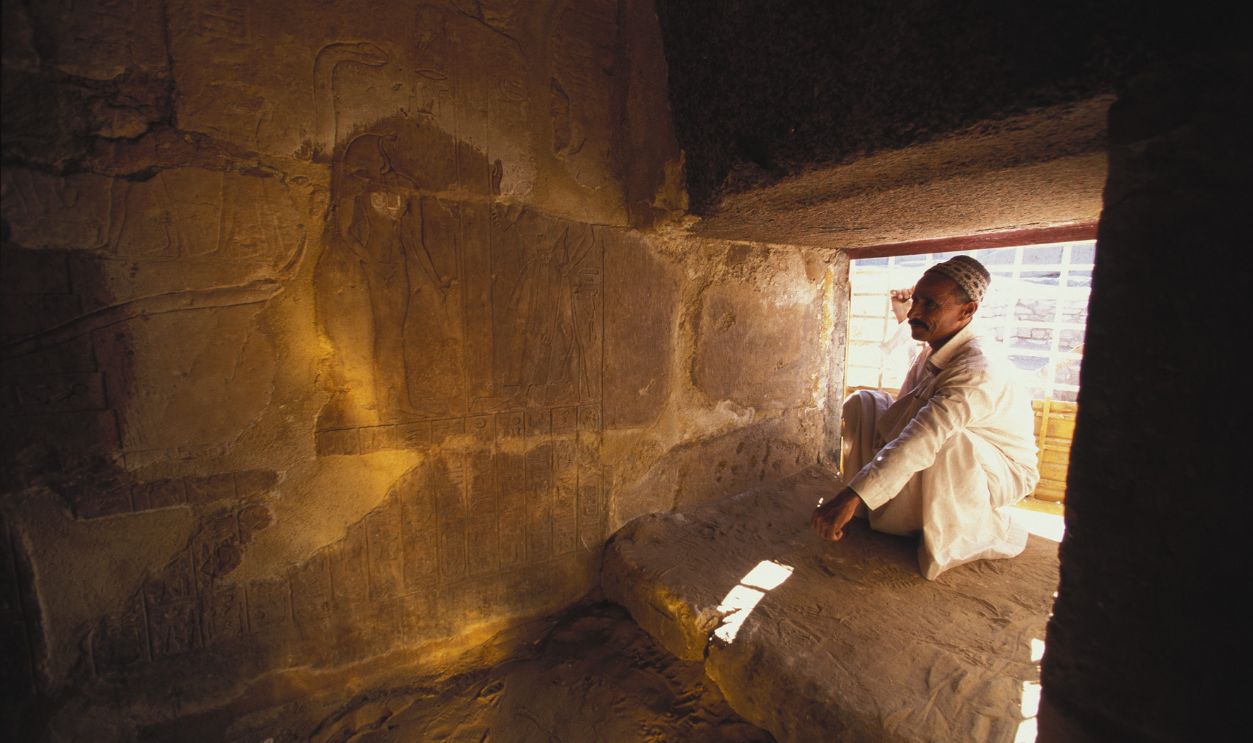

Patrick AVENTURIER, Getty Images

Patrick AVENTURIER, Getty Images

Or Were His Remains Moved Later?

Another possibility is that Shoshenq III was originally buried elsewhere (perhaps in the tomb he commissioned) and that later rulers moved his burial goods into Osorkon II’s tomb to protect them from looters or during political upheaval. Both scenarios are being explored by archaeologists.

Jon Bodsworth, Wikimedia Commons

Jon Bodsworth, Wikimedia Commons

What This Says About Third Intermediate Period Politics

The Third Intermediate Period was a time of internal conflict and shifting alliances. Royal tombs, once secure signs of eternal kingship, became vulnerable to reuse, repurposing, and political interference. The Tanis discovery brings that reality into sharp relief.

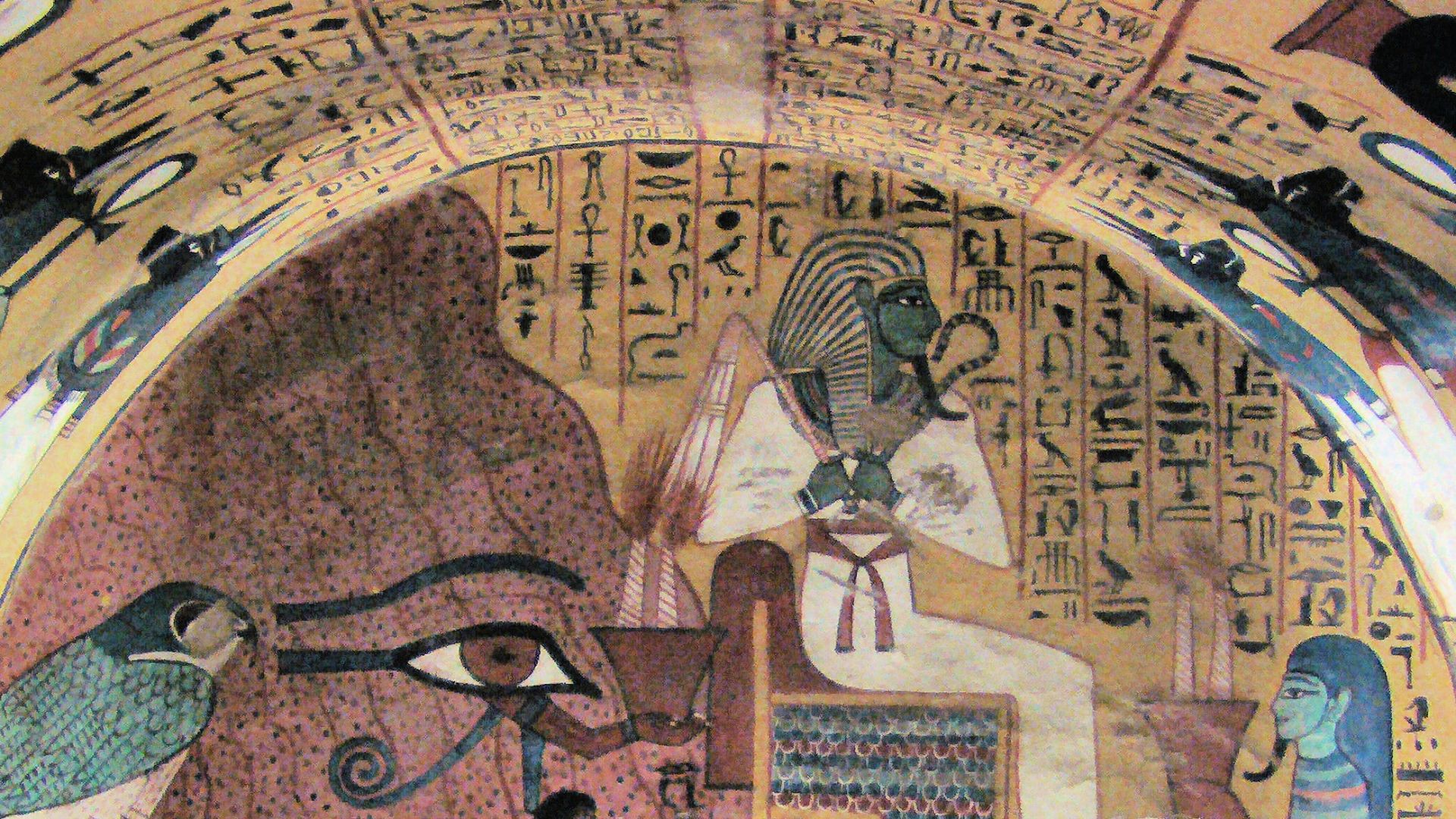

kairoinfo4u, Wikimedia Commons

kairoinfo4u, Wikimedia Commons

New Clues From Old Stones

As researchers continue to analyze the ushabti, sarcophagus, and associated inscriptions, they hope to refine their understanding of what exactly happened. Were we witnessing a deliberate cover-up, a calculated dynastic statement, or a pragmatic response to looting threats? Each possibility opens new windows into ancient Egyptian power dynamics.

Wilhelm Spiegelberg (1870 – 1930), Wikimedia Commons

Wilhelm Spiegelberg (1870 – 1930), Wikimedia Commons

Beyond Tanis: Broader Implications

This discovery doesn’t just reshape our understanding of one pharaoh’s burial. It also challenges how historians view royal burial customs across troubled eras, especially when political unity was weak and dynastic legitimacy was in flux.

Final Thoughts

The story of Shoshenq III’s burial under the name of another king could be one of political maneuvering, dynastic strategy, or even ancient crisis management. Whatever the true explanation, this remarkable find at Tanis offers a rare glimpse into the messy, complex, and deeply human side of ancient Egyptian royalty—where death, honor, ambition, and legacy intersected in stone, silt, and silence.

Juan R. Lazaro, Wikimedia Commons

Juan R. Lazaro, Wikimedia Commons

You May Also Like: