The Planet’s Safety Net Is Unraveling

A new global map has revealed a startling truth—over half of Earth’s land is now operating outside the planet’s “safe zone” for maintaining life-supporting ecosystems. Scientists describe it as a breach of what they call functional biosphere integrity—a threshold that marks when natural systems stop working the way they’re supposed to.

A Planet Under Strain

Published in One Earth and led by researchers from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), the study found that roughly 60% of global land has already crossed this boundary, with 38% of it classified as high risk.

H. Raab (User:Vesta), Wikimedia Commons

H. Raab (User:Vesta), Wikimedia Commons

What That Means for Us

In simple terms, most of the land we rely on to grow food, store carbon, and regulate water is now under severe ecological stress. These systems are still functioning—but only barely.

What Does “Functional Biosphere Integrity” Mean?

This scientific term essentially refers to the planet’s ability to keep its ecosystems functioning. It’s about whether forests still regulate carbon, soils can hold nutrients, and wetlands still filter water. When this integrity is lost, ecosystems may still exist, but they no longer function in ways that sustain the planet—or us.

Filipefrazao, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Filipefrazao, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

A Global Danger Zone

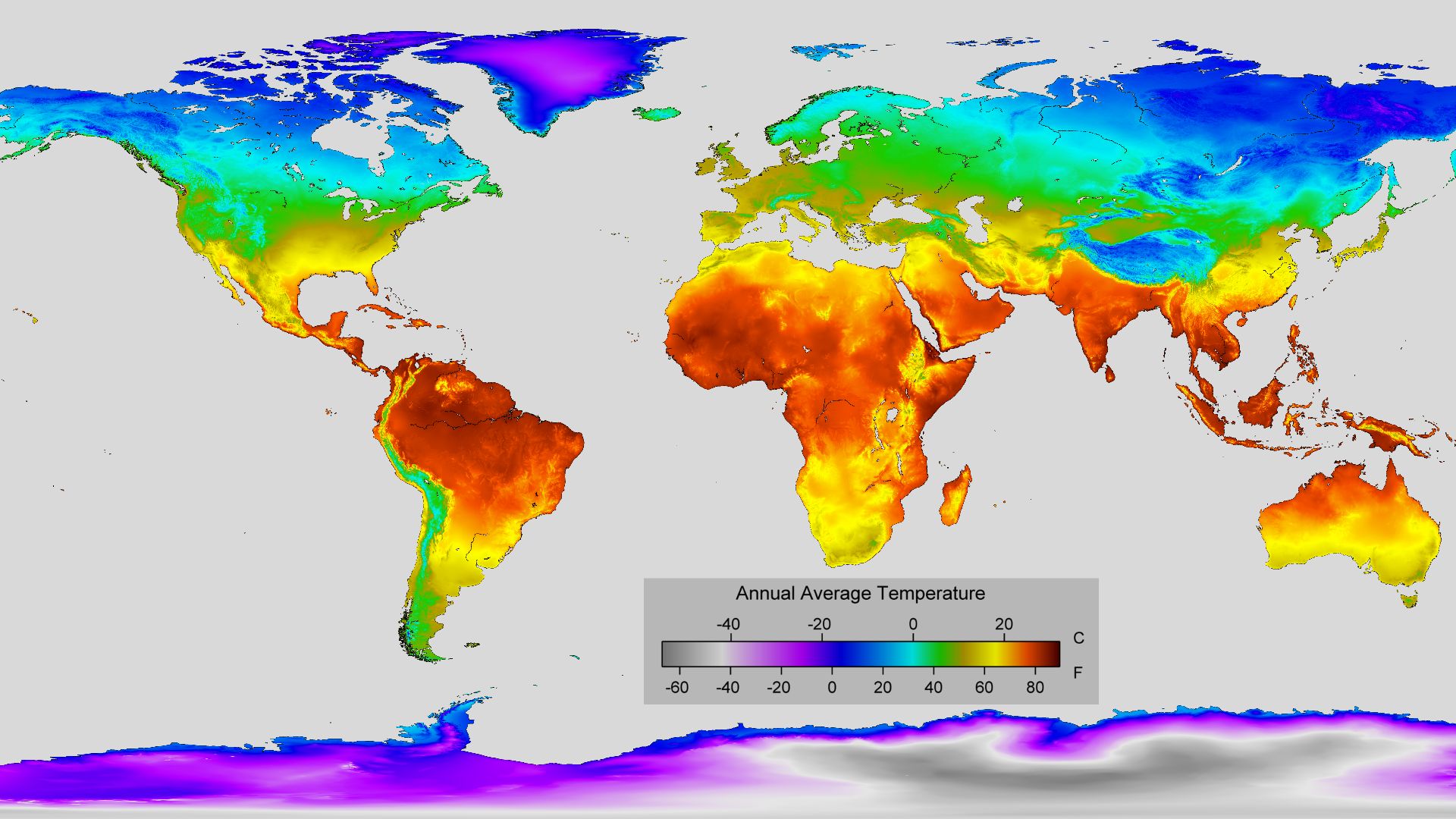

The research team created the first global map of biosphere integrity, showing where ecosystems have shifted beyond stability. By their estimates, the safe operating space has been surpassed on 60% of land surfaces worldwide. As co-author Dr. Wolfgang Lucht of PIK explained, “The framework now squarely puts energy flows from photosynthesis in the world’s vegetation at the centre of those processes that co-regulate planetary stability… humans are now diverting a sizeable fraction of them.”

How Scientists Mapped It

The study combined two main measurements:

- HANPP (Human Appropriation of Net Primary Production): how much natural plant growth and biomass humans harvest or destroy.

- EcoRisk: how changes in vegetation, carbon, and water cycles indicate ecosystem stress or collapse.

Modeling the Planet’s Vital Signs

Researchers used the LPJmL biosphere model at half-degree resolution to classify each region as Safe, Increasing Risk, or High Risk. This method helped scientists identify where ecosystems are failing—and how far they’ve drifted from safe conditions.

Art & Figures, Potsdam, Germany., Wikimedia Commons

Art & Figures, Potsdam, Germany., Wikimedia Commons

It’s Been Happening for Centuries

This isn’t a sudden collapse. According to the study, by 1900, about 37% of land had already crossed local ecological thresholds. That number has nearly doubled in the modern era, largely due to agriculture, deforestation, and industrialization.

IndoMet in the Heart of Borneo, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

IndoMet in the Heart of Borneo, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Where the Planet Is Hurting Most

The map shows Europe, Asia, and North America among the most heavily degraded regions. Centuries of farming, logging, and development have left little ecological buffer. Tropical zones in South America and Africa are also under pressure as forests are cleared and climate patterns shift.

It’s Not Just About Losing Species

Unlike traditional biodiversity metrics, this study isn’t simply counting species—it’s measuring function. A forest can look lush yet still be failing if it no longer regulates water or stores carbon effectively. It’s like a car with a shiny exterior but a broken engine.

A Map That Redefines Risk

What makes this research unique is its scale and specificity. Instead of vague global warnings, scientists now have a detailed map showing exactly where ecosystems are most at risk. It’s a sobering visual—entire continents shaded in red, signaling lands where nature is stretched thin.

Robert A. Rohde / Berkeley Earth, Wikimedia Commons

Robert A. Rohde / Berkeley Earth, Wikimedia Commons

Earth’s Life Systems Are Losing Their Safety Net

Across vast regions, the natural systems that make life stable and abundant are beginning to fail. Forests, wetlands, and grasslands are losing their ability to buffer heat, retain water, and regenerate after shocks. The very mechanisms that once kept our planet resilient are now faltering under relentless human pressure and a changing climate.

Quantifying the Strain on the Biosphere

As lead author Dr. Fabian Stenzel explained, “There is an enormous need for civilisation to utilise the biosphere… It is therefore becoming even more important to quantify the strain we’re already putting on the biosphere, and to identify overloads.” In that sense, much of the planet has truly become unsafe for life as we’ve known it—not lifeless, but far less capable of sustaining balance and abundance.

Human Demand Is Driving the Breach

Humanity currently diverts about one-quarter of all global biomass production—essentially hijacking photosynthesis to feed, clothe, and fuel ourselves. When we take too much, the systems that replenish that biomass begin to fail. Over time, that can trigger cascading feedback loops: soil erosion, drought, wildfires, and crop losses.

The Feedback Loop Problem

Once ecosystems are degraded, they can worsen climate change. Degraded soils release carbon instead of storing it, and reduced vegetation means less natural cooling.

When Nature Stops Protecting Us

The more we weaken the biosphere, the less it can protect us from heat waves, storms, and food insecurity. These feedbacks are why scientists warn that losing functional integrity isn’t just environmental—it’s existential.

Regional Examples

In parts of Europe, centuries of cultivation have left soils nutrient-poor and carbon-depleted. In the Amazon, deforestation has pushed sections of the rainforest toward a “savanna state.” Across the U.S. Midwest, intensive agriculture has drained wetlands and eroded topsoil. Each case reflects a different route to the same outcome: ecological instability.

Ibama from Brasil, Wikimedia Commons

Ibama from Brasil, Wikimedia Commons

A Warning

The study’s authors stress that these risks aren’t irreversible. “The framework now allows us to map where and when the safe operating space for humanity has been transgressed,” noted Dr. Lucht. “But it also helps identify where recovery is still possible.”

What Can Be Done?

Restoration and rewilding projects can help bring some areas back within safe limits. Reducing biomass extraction, expanding protected areas, and managing agriculture more sustainably are key steps. But time is short—the longer ecosystems stay in the red, the harder recovery becomes.

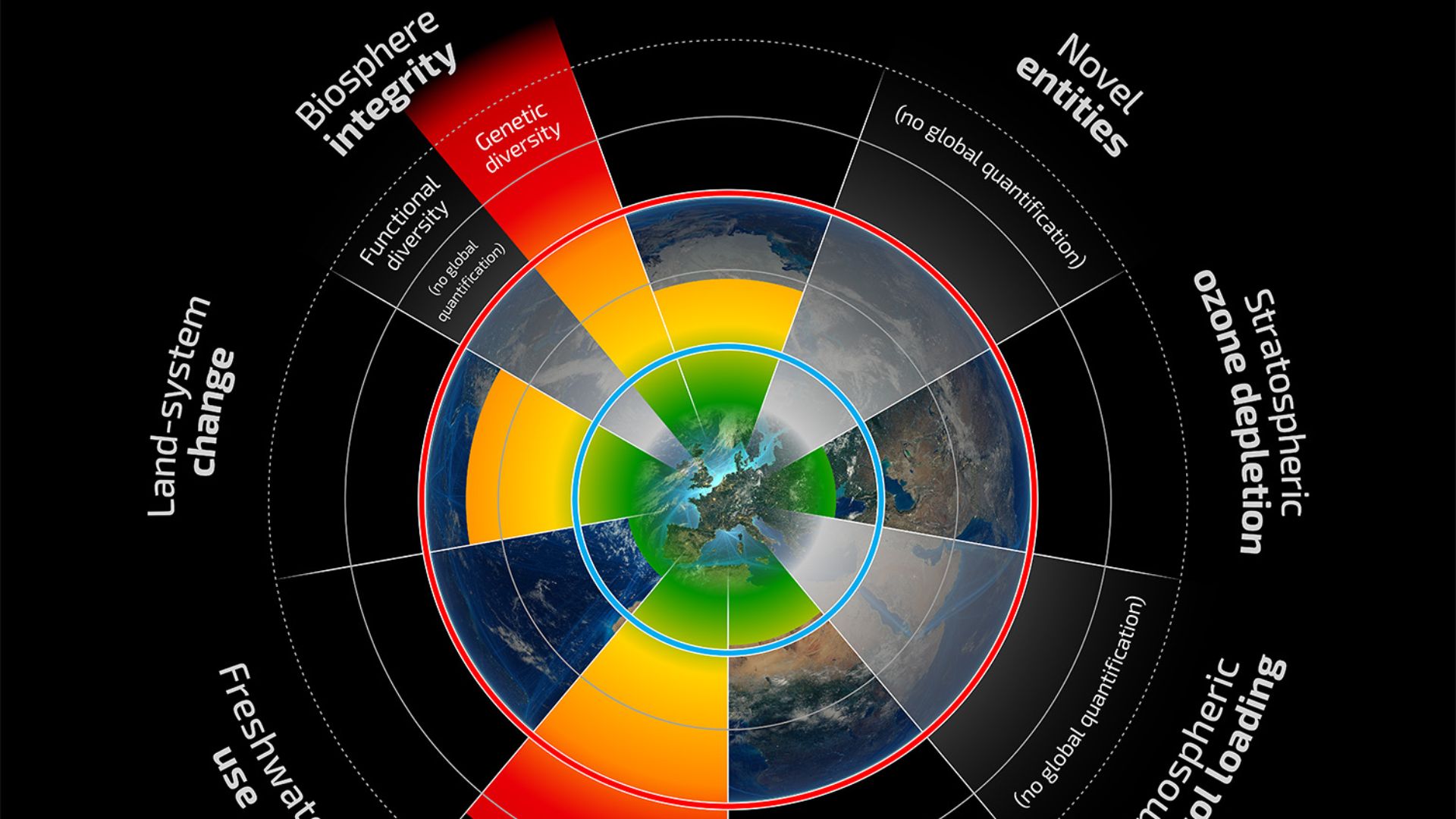

A Call for Joined-Up Thinking

The researchers argue that climate policy and biosphere policy can’t be separate. Protecting forests, soils, and vegetation isn’t a side issue—it’s core climate action. As Johan Rockström emphasized, “Governments must treat it as a single overarching issue: comprehensive biosphere protection together with strong climate action.”

Stefanie Loos / re:publica from Germany, Wikimedia Commons

Stefanie Loos / re:publica from Germany, Wikimedia Commons

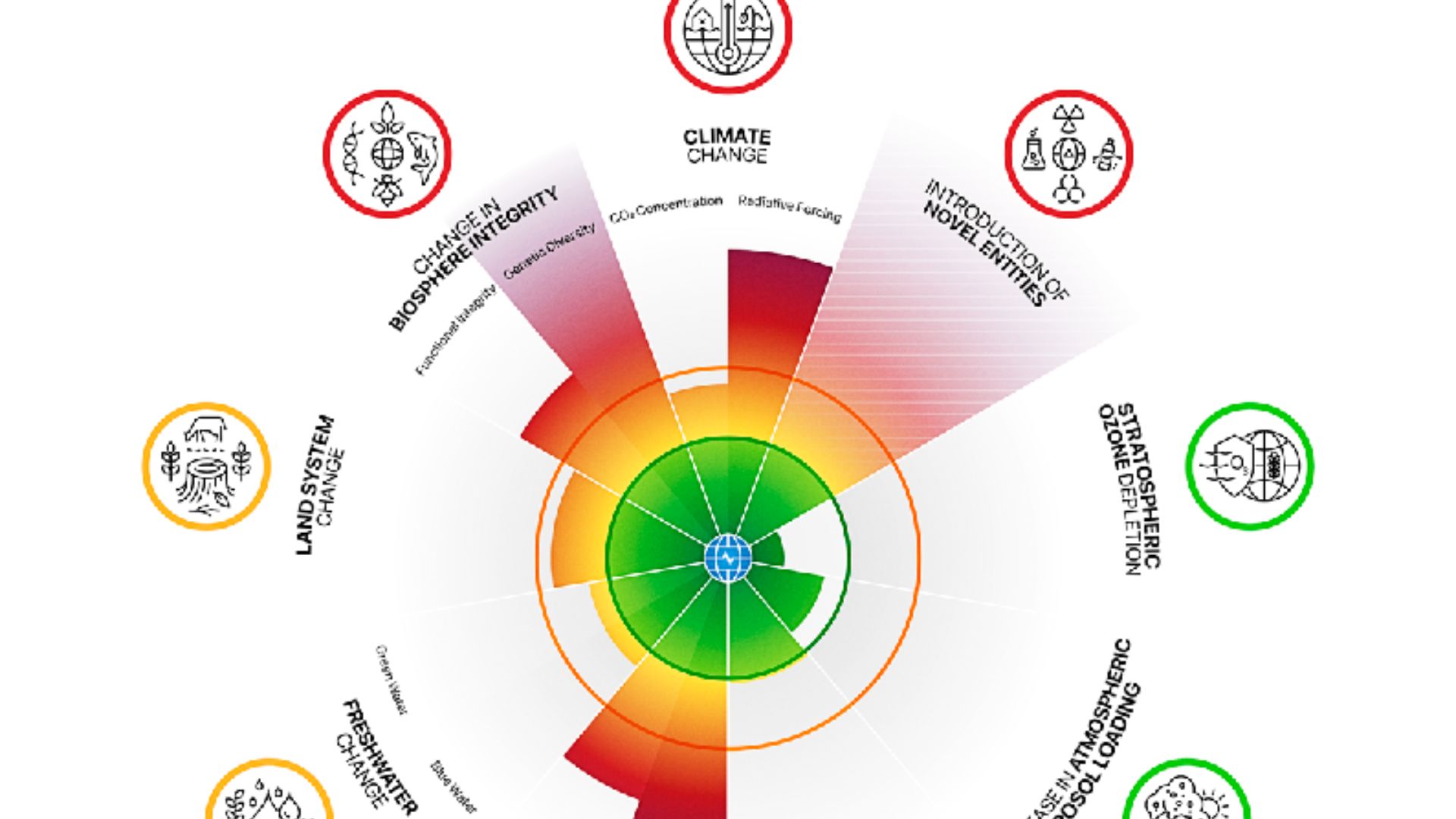

A Look Back to the Planetary Boundaries Framework

This new study builds on the influential Planetary Boundaries model introduced by Johan Rockström and colleagues in 2009, which defined nine essential systems (like climate, freshwater, and biodiversity). Functional biosphere integrity is one of the most critical—and one of the most breached.

Owenmgaffney, Wikimedia Commons

Owenmgaffney, Wikimedia Commons

The Human Factor

It’s easy to imagine this as a distant scientific problem, but it’s directly linked to how we live: our diets, consumption patterns, and land use. The boundary isn’t just a number—it’s a reflection of how deeply our species has reshaped the planet’s biology.

The Bottom Line

Earth’s systems aren’t collapsing overnight—but the margin of safety is gone. The biosphere is still functioning, but in many places, it’s doing so on borrowed time. Unless humanity restores balance, the map showing “unsafe zones” may become the new normal.

You Might Also Like: