Teeth That Changed Everything

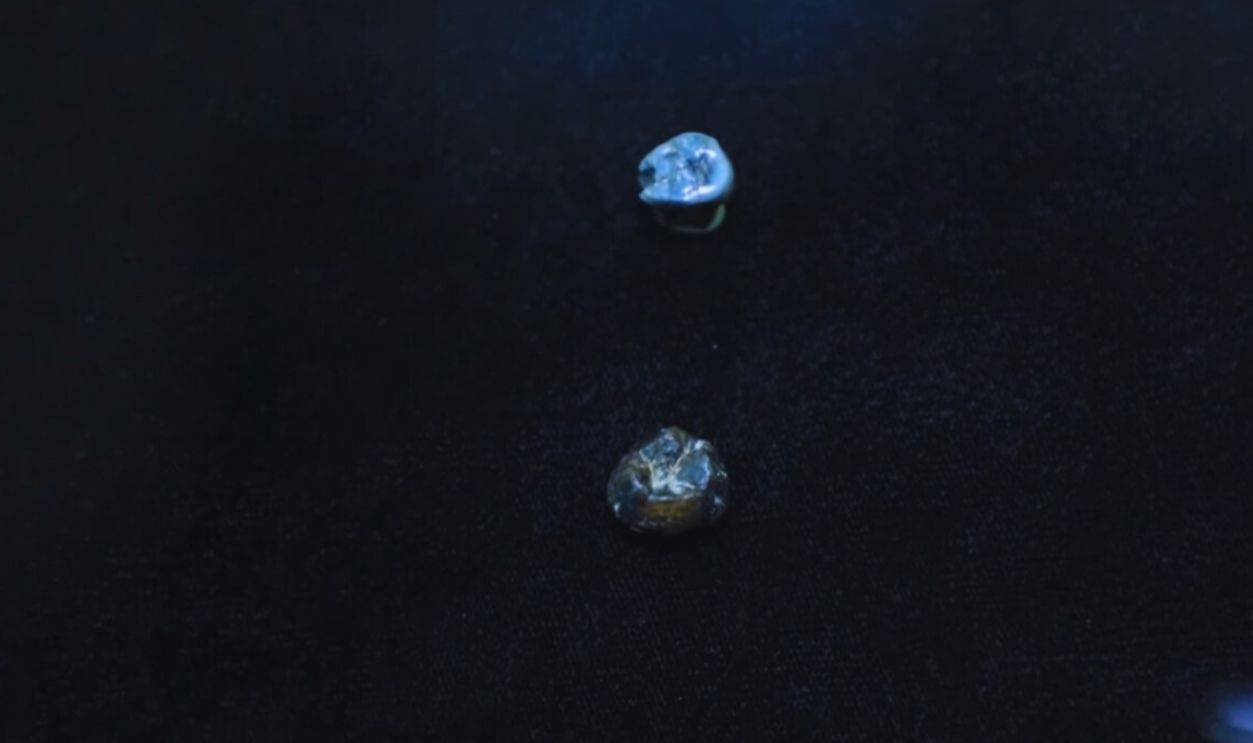

Deep in Ethiopia, scientists have uncovered fossil teeth. But these aren’t just any old teeth. This tiny find is shaking up everything we thought we knew about human evolution—pointing to a brand-new species of Australopithecus that lived side by side with the very first humans nearly 2.6 million years ago. A small discovery with big—no, huge—consequences.

The Textbook Version

The Textbook Version

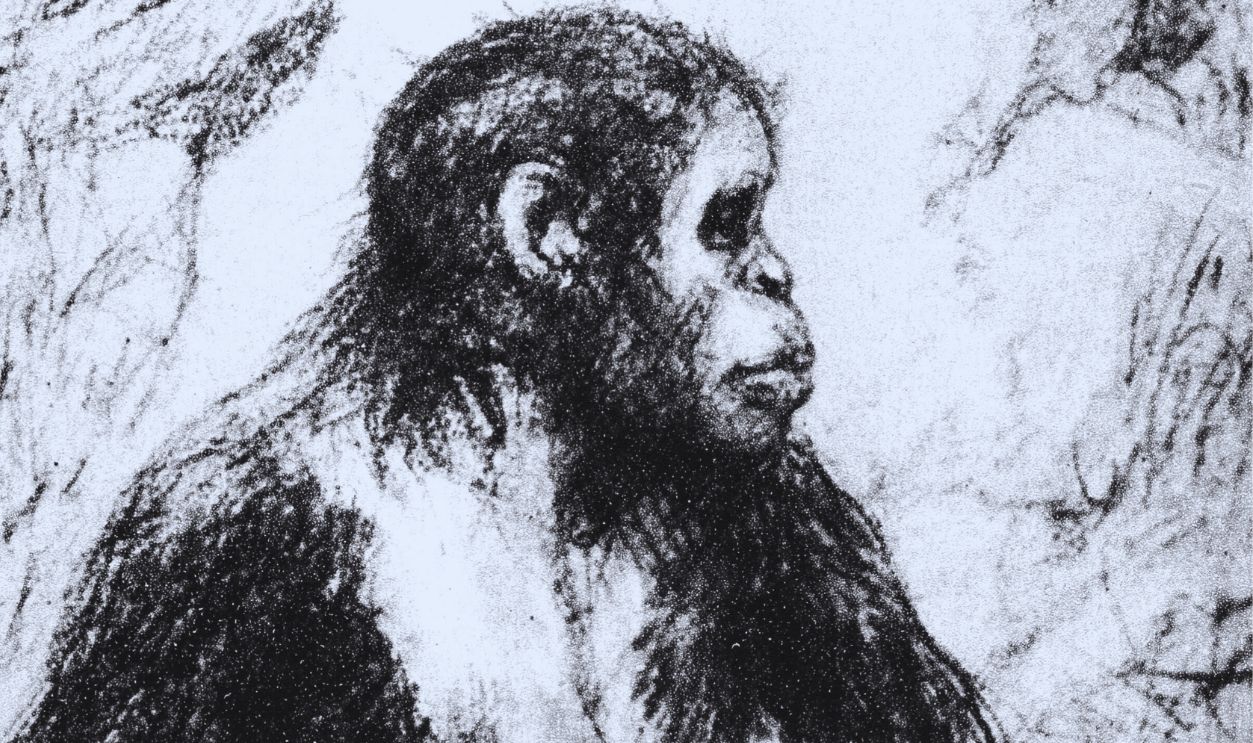

For decades, we pictured human evolution like a neat ladder: ape to australopithecine to Homo to us. Simple, straight, inevitable. But nature rarely works in straight lines. These fossils suggest the story was more complicated, with different species overlapping and living at the same time. Overearth, Getty Images

Overearth, Getty Images

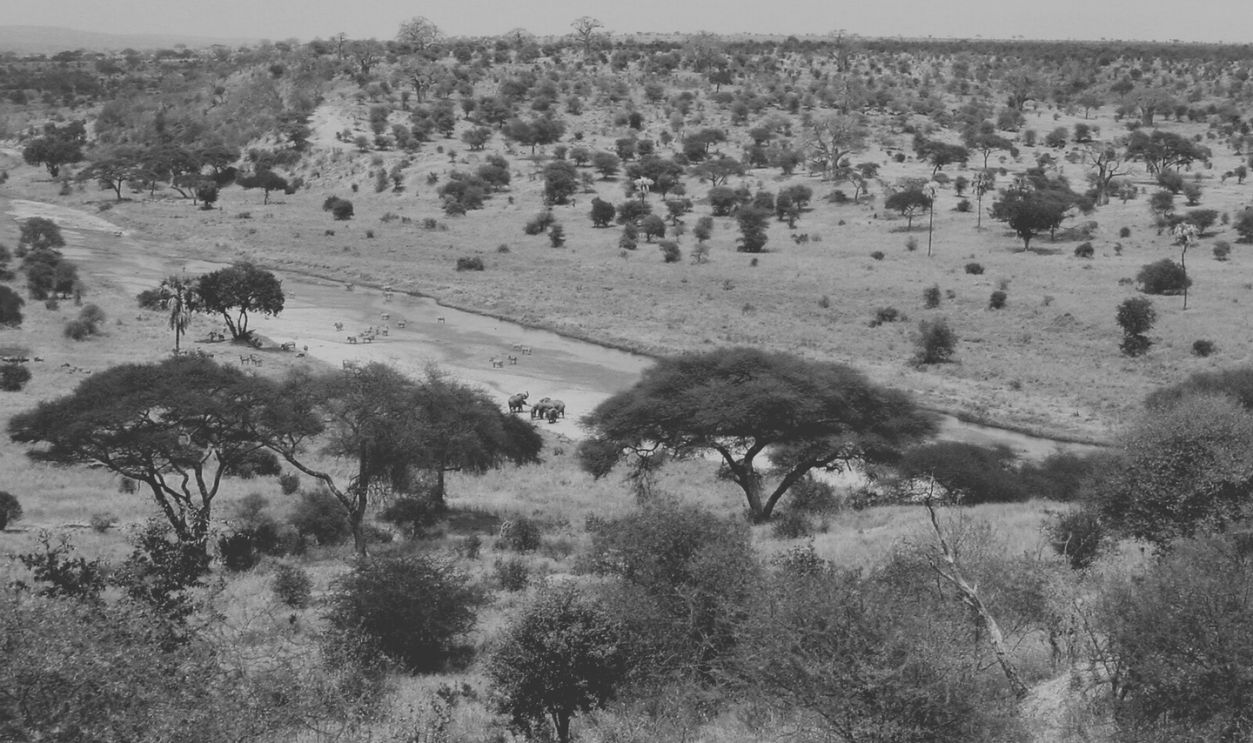

Welcome to Ledi-Geraru

In Ethiopia’s Afar region lies Ledi-Geraru, a treasure chest of ancient bones. Just a stone’s throw from where Lucy (Australopithecus afarensis) was found, this site preserves the crucial window between 3 and 2 million years ago—exactly when humans were first emerging. And this isn’t the first time it’s made headlines either.

The Jaw That Rocked the World

Back in 2013, researchers discovered LD 350-1, a jawbone dating to about 2.78 million years ago. It was hailed as the earliest Homo fossil ever found and instantly made the site famous. That jawbone suggested the dawn of our genus began earlier than expected—but the bigger surprise came later with a set of teeth.

Brian Villmoare, Wikimedia Commons

Brian Villmoare, Wikimedia Commons

Unearthed Between 2015 and 2018

During field surveys from 2015 to 2018, scientists spotted 13 fossil teeth eroding out of the ground. At the time, they carefully logged and stored them for study. No headlines yet—just dusty fragments in a field notebook. But after years of studying and comparing the teeth...

Teeth of new human ancestor discovered in Ethiopia, AP Archive

Teeth of new human ancestor discovered in Ethiopia, AP Archive

Announced in 2025

A decade after the first teeth were found, the research team finally published their findings in August 2025. And it was then that the world learned these weren’t ordinary teeth—that they pointed to a brand-new species of Australopithecus.

And here’s why that matters.

13 Teeth, Two Lineages

The collection turned out to be split: ten of the teeth looked like Australopithecus, while three clearly matched early Homo. Both came from the same layers of rock. That means these lineages weren’t separated by time or geography—they lived in the same place, at the same time, in the same environment.

Clocking the Age

Dating was possible thanks to volcanic ash layers that sandwiched the fossils. Radiometric analysis pinned the teeth between 2.6 and 2.8 million years old. Fossils from that era are incredibly rare, which makes these teeth some of the most valuable evidence for this period in human origins.

Teeth Unlike Any Other

When scientists compared the Australopithecus teeth with known species like Lucy’s A. afarensis and the younger A. garhi, the differences stood out. Enamel thickness, cusp patterns, and dimensions didn’t fit any category. That was enough for researchers to propose a new species—an ancient cousin now added to the family tree.

A Crowded Family Tree

This discovery adds yet another branch to a lineup that already included early Homo, Paranthropus, and A. garhi. Instead of one species replacing another, multiple types of hominins were coexisting in East Africa during this period. Imagine four close relatives, each trying a slightly different way of surviving in the same environment.

Life on the Drying Plains

The late Pliocene was a time of environmental change. Africa was becoming drier, with forests shrinking and grassy plains expanding. Fossilized grazing animals confirm this shift. These conditions likely forced hominins to adjust their diets and behaviors. Adaptability was critical, and species that couldn’t adapt eventually disappeared.

Who Made the First Tools?

Stone flakes and cores have been reported from the Bokol Dora 1 (BD-1) site in the Ledi-Geraru region, dating to about 2.6 million years ago. They are contenders for the earliest Oldowan tools, though the dating and interpretation are still debated. Early Homo is the strongest candidate for their maker, but some researchers suggest an Australopithecus could have made them as well.

Didier Descouens, Wikimedia Commons

Didier Descouens, Wikimedia Commons

Survival Strategies in Teeth

Teeth hold clues to diet. The wear and enamel patterns in these fossils suggest tougher, possibly more varied food choices than Lucy’s kind. Maybe roots, seeds, or gritty vegetation. Each group had its own way of surviving, which may have reduced direct conflict but also created competition in overlapping areas.

Coexistence or Showdown?

What did it mean to have multiple hominins living in the same place? Did they compete for resources, or occupy different niches? We don’t know for sure. What we do know: only Homo’s branch survived. This cousin eventually vanished, leaving only teeth as evidence of its existence.

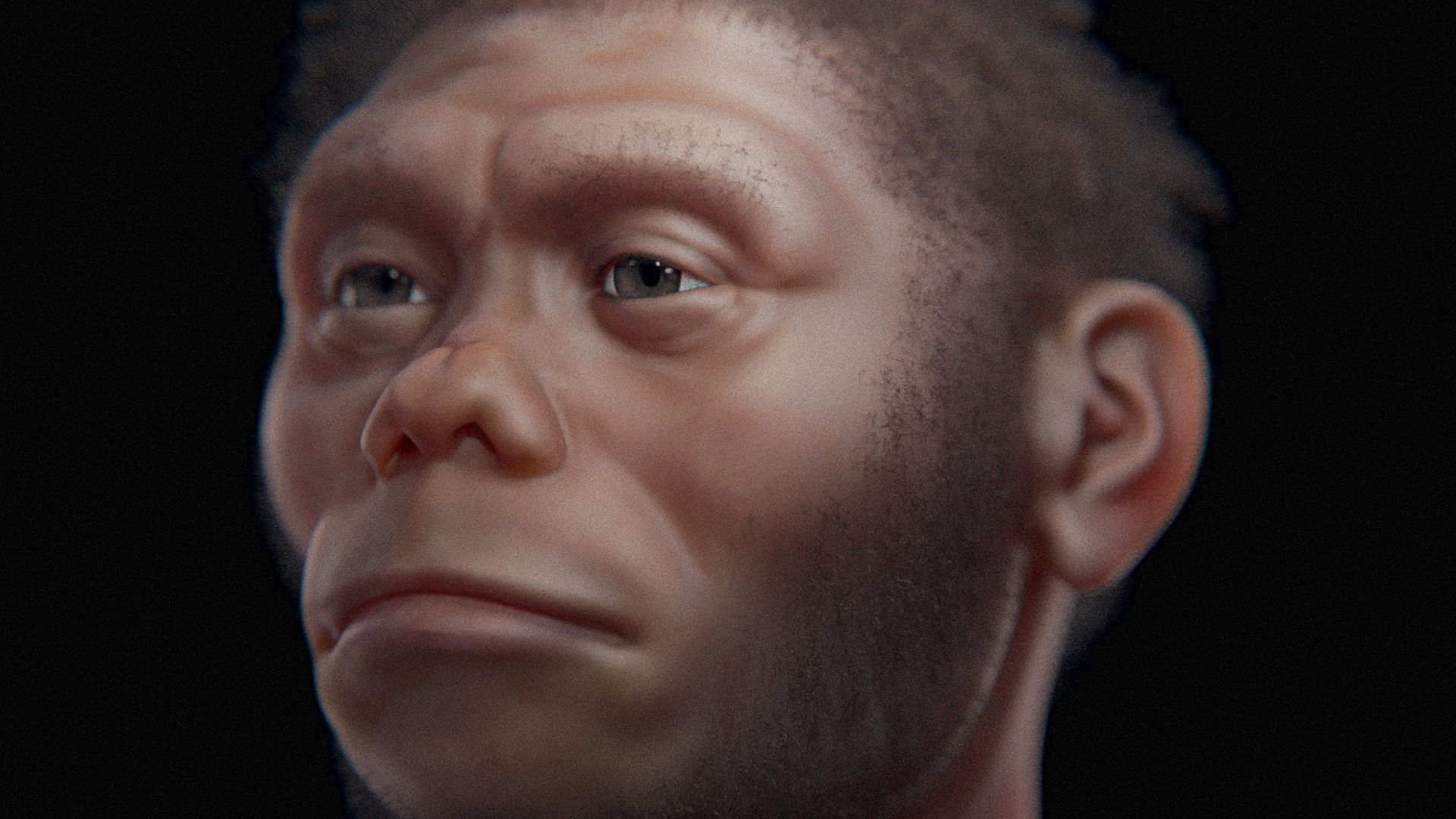

Cicero Moraes, Wikimedia Commons

Cicero Moraes, Wikimedia Commons

Quotes from the Field

Lead researcher Brian Villmoare explained: “The new finds of Homo teeth from 2.6- to 2.8-million-year-old sediments — reported in this paper — confirms the antiquity of our lineage.”

Co-director Kaye Reed added perspective: “Human evolution is not linear — it’s a bushy tree; there are life forms that go extinct.”

Skeptics Speak Up

Not everyone is ready to call this a new species. Some scientists argue that teeth alone aren’t enough—they could just represent variation within a known group. Until more fossils like jaws or skulls are found, the claim stays cautious. But most agree the evidence points to something unusual.

A Tangled Bush, Not a Ladder

Even skeptics agree the bigger picture has shifted. These fossils prove that multiple species of hominins were around at the dawn of Homo. The idea of a straight evolutionary ladder doesn’t hold up. Instead, it looks more like a tree with many branches, most of which ended long before reaching us.

Tim Evanson, Wikimedia Commons

Tim Evanson, Wikimedia Commons

Why This Cousin Matters

This newly proposed Australopithecus species may not connect directly to us, but its presence shows how many different evolutionary options were being tested. Dozens of possibilities existed, but only one line continued. Our existence comes down to which branch happened to last, not inevitability.

Wolfgang Sauber, Wikimedia Commons

Wolfgang Sauber, Wikimedia Commons

Meet the Scientists

The discovery comes from the Ledi-Geraru Research Project, co-directed by paleoanthropologist Kaye Reed. Her team has been working in the region since the early 2000s, carefully piecing together a picture of this key time period. The 2025 publication represents the culmination of years of painstaking work.

What We Still Don’t Know

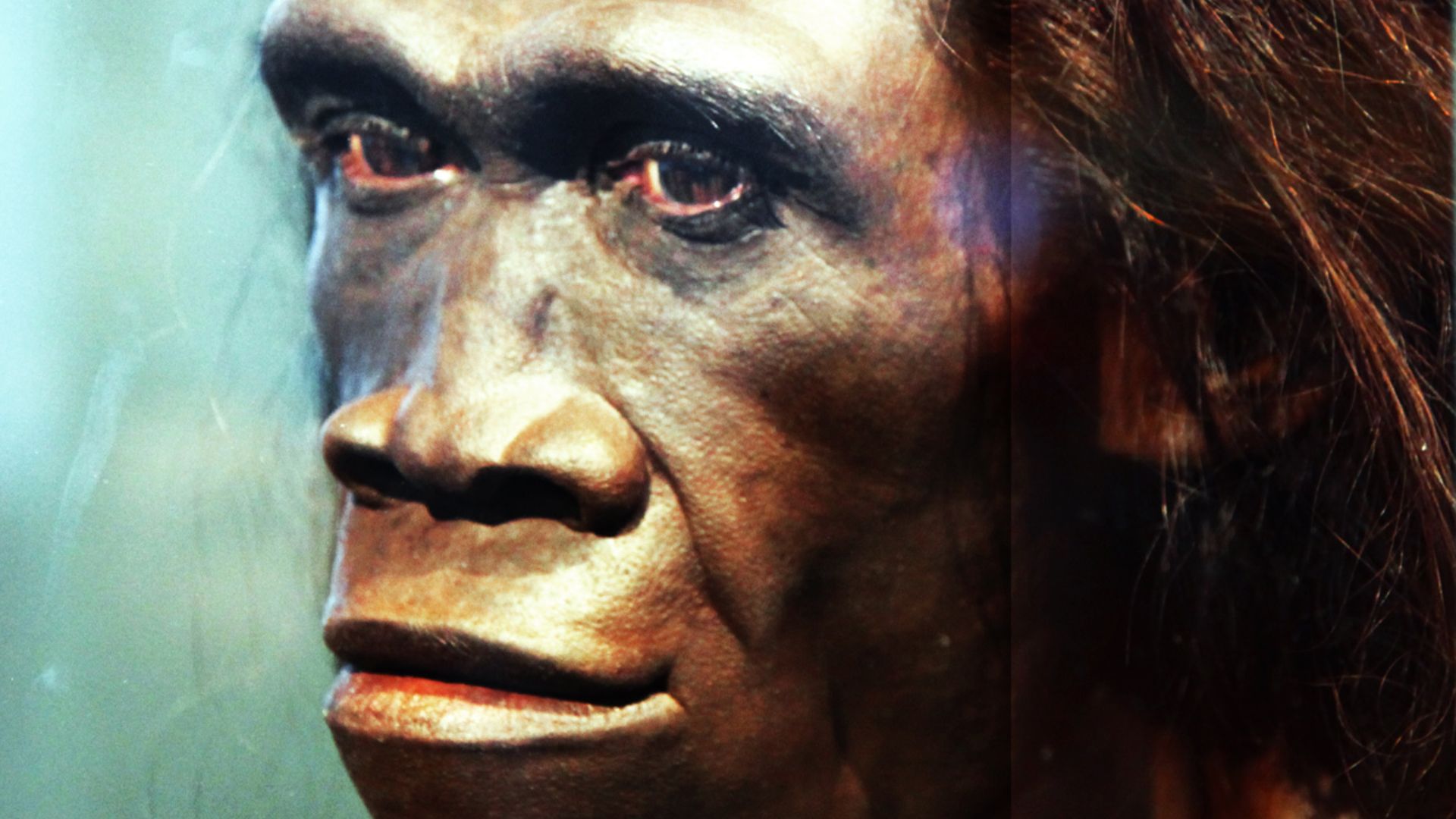

Without a skull, jawbone, or skeleton, the identity of this species is still uncertain. Was it tall or short? More ape-like or human-like? Did it walk upright, or use tools? The teeth provide some information, but most of the story is still hidden in the ground.

UniversalImagesGroup, Getty Images

UniversalImagesGroup, Getty Images

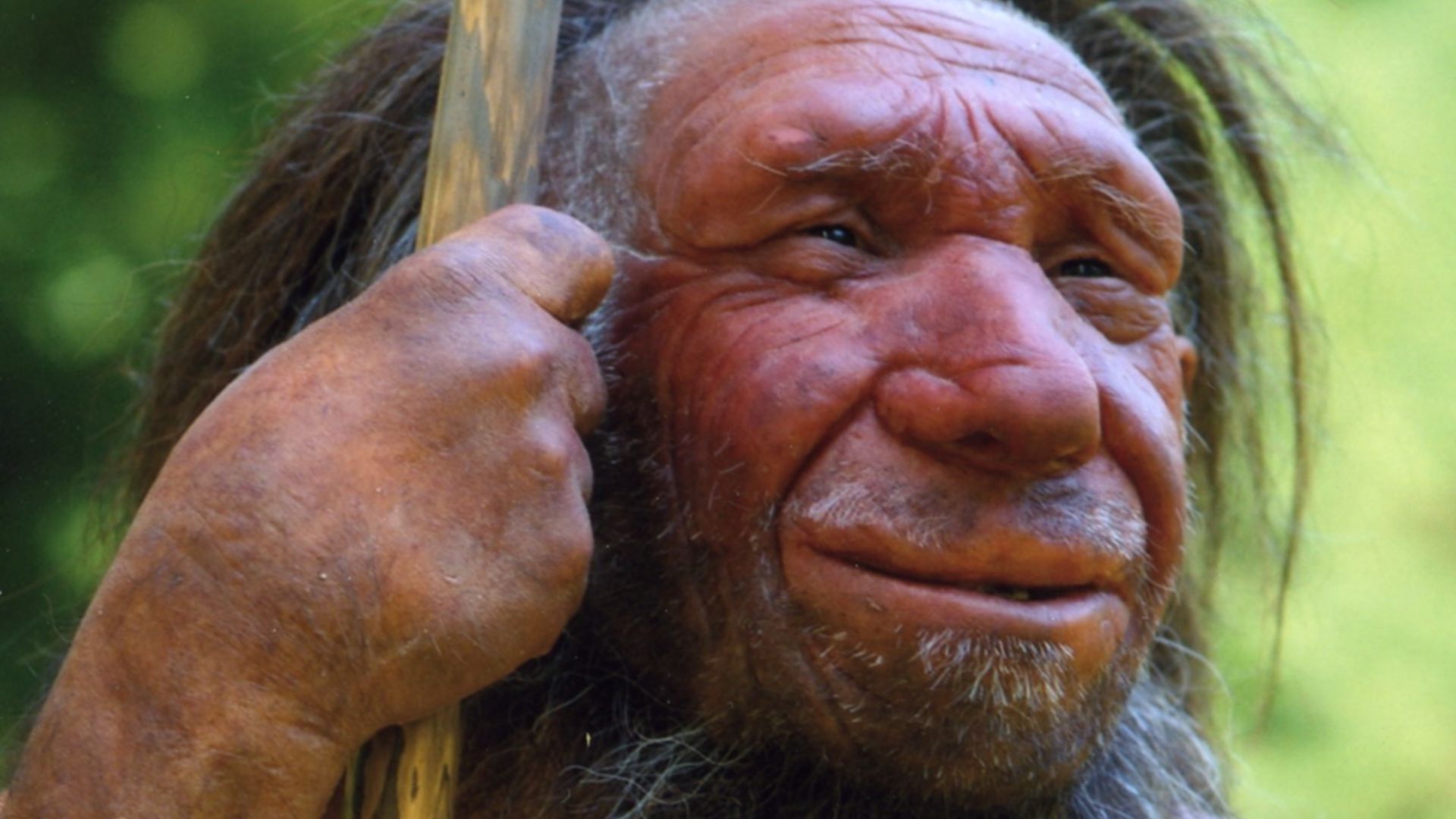

Echoes Around the World

Other finds back up this pattern. Homo naledi in South Africa and Homo floresiensis in Indonesia also challenged assumptions about who lived when and where. The Ledi-Geraru teeth now sit alongside these discoveries as reminders that evolution is less predictable than we used to believe.

Cicero Moraes, Wikimedia Commons

Cicero Moraes, Wikimedia Commons

The Hunt Continues

Excavations at Ledi-Geraru are ongoing. The team hopes to find a skull, a jaw, or even limb bones that could give this species a clearer identity. Until then, these teeth remain a glimpse into a hidden branch of our family tree, waiting for more pieces to fall into place.

Rethinking the March of Progress

That famous “ape-to-man” museum poster has always been misleading. Evolution wasn’t a single file of species replacing one another. It was a set of overlapping groups, some thriving while others faded away. These teeth underline that reality more clearly than ever.

A Humbling Reminder

The survival of Homo wasn’t inevitable. Many lineages once lived, adapted, and disappeared. We’re only here because one of them lasted. These fossils remind us that survival is fragile, and our place in this story is not guaranteed—it was just one possible outcome.

Neanderthal-Museum, Mettmann, Wikimedia Commons

Neanderthal-Museum, Mettmann, Wikimedia Commons

You Might Also Like:

Sources: 1, 2, 3