Echoes Of Forgotten Ancestors

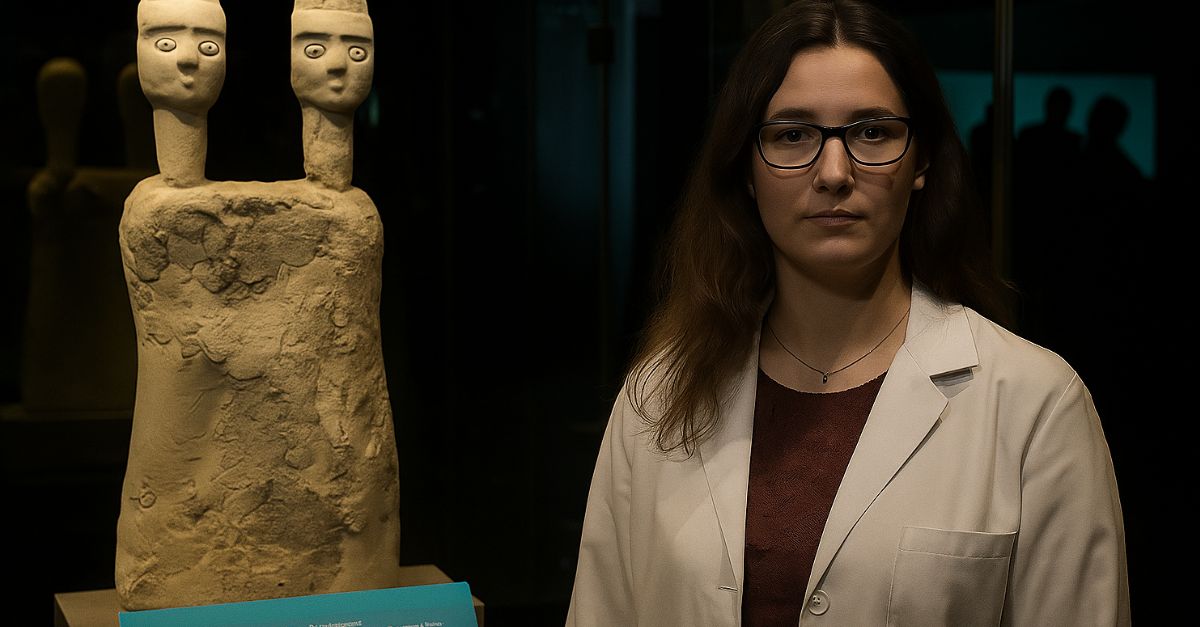

In the hills near Amman, Jordan, archaeologists uncovered statues unlike anything the ancient world had ever seen. With eyes that seem alive and an unsettling presence, these figures may hold answers about belief and identity.

A Bulldozer Uncovers History By Accident

In 1974, construction teams laying a new road between Amman and Zarqa accidentally exposed the Neolithic site of Ain Ghazal in Jordan. This unexpected discovery brought to light a sprawling prehistoric village and, later, astonishing statues buried beneath its surface, reshaping our understanding of early human society in the Levant.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Wikimedia Commons

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Wikimedia Commons

What Lay Beneath The Soil Of Amman In 1983

A decade after the road-building discovery, archaeologists digging near Amman in 1983 encountered a deep pit about 8 feet down. Inside lay exquisitely preserved caches of lime plaster statues intentionally buried under the floors of ancient homes—an archaeological revelation that stunned scholars worldwide.

David Bjorgen, Wikimedia Commons

David Bjorgen, Wikimedia Commons

A Prehistoric City Hidden In Plain Sight

Ain Ghazal thrived between roughly 7250 BCE and 5000 BCE as a major pre-Pottery-Neolithic settlement covering 10–15 hectares. Home to as many as 3,000 people at its peak, it was four to five times larger than contemporary Jericho—yet this metropolis lay unrecognized for millennia beneath modern Jordan.

Jared Sluyter jaredsluyter, Wikimedia Commons

Jared Sluyter jaredsluyter, Wikimedia Commons

Among The Largest Settlements Of Its Time

At its zenith around 7000 BCE, Ain Ghazal encompassed as much as 15 hectares, which is a remarkable scale for the era. This size explains its importance as a central hub of early agriculture, community life, and complex social organization in the Neolithic Levant.

Bashar Tabbah, Wikimedia Commons

Bashar Tabbah, Wikimedia Commons

Why Did Archaeologists Call It A World-Changing Find?

This discovery of Ain Ghazal rewrote the narrative of Neolithic society. The statues rank among the oldest large-scale human representations, and their details and concealment challenged prevailing assumptions about prehistoric art and social complexity in the ancient Near East.

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

Discovering Figures That Defy Expectations

When archaeologists in 1983–1985 discovered 15 full statues and 15 busts buried beneath abandoned houses at Ain Ghazal, the artistry and preservation stunned experts. These large lime plaster figures, unlike the era’s small clay or stone figurines, introduced a bold new scale to prehistoric art.

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

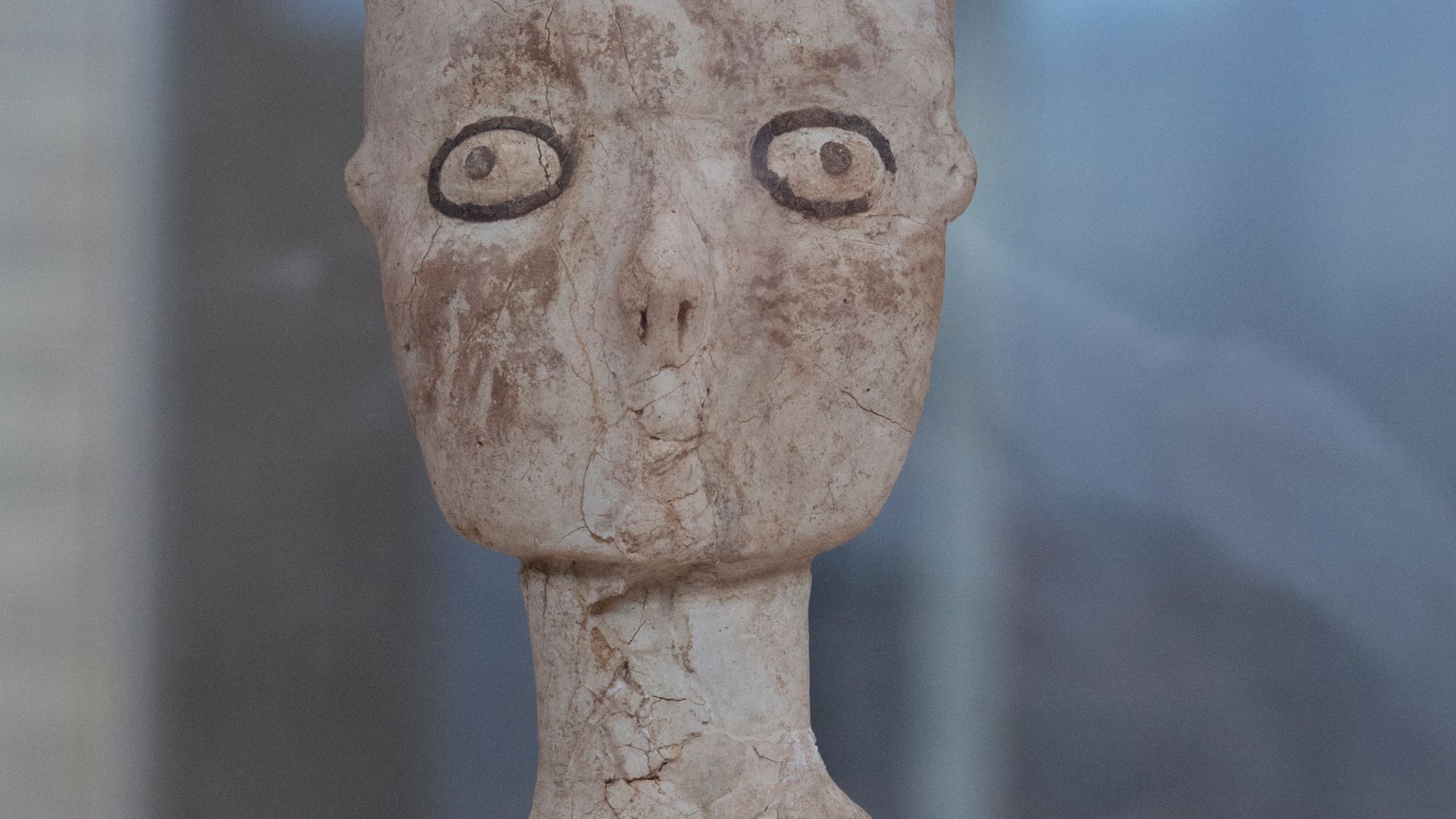

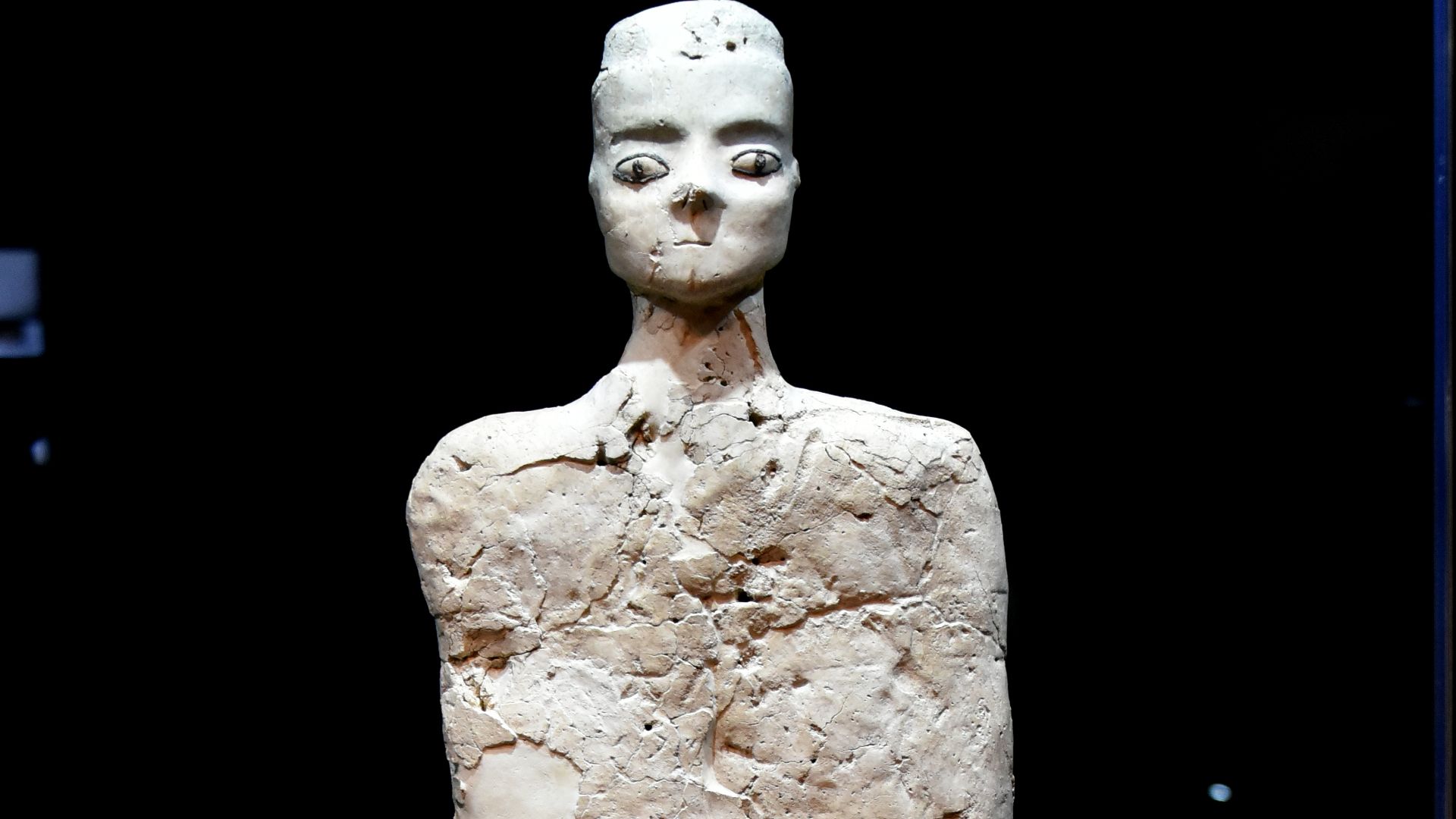

Eyes That Seem Alive Across Millennia

The heads of the statues feature disproportionately large eyes, created with a bitumen outline that emphasizes their gaze. They appear hauntingly lifelike even today. This striking feature suggests an intentional design choice, focused on presence and perhaps spiritual resonance, not merely physical depiction.

Realistic Faces Paired With Abstract Bodies

At Ain Ghazal, the figures’ heads are beautifully detailed, while the torsos are simplified, flat, and abstract. The sharp contrast between expressive facial features and minimalistic bodies highlights that identity or presence that was captured through the face was paramount in their creation.

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

Giants In A World Of Miniature Ritual Objects

At roughly 3 feet tall, the statues tower over the miniature figurines of their time. These monumental figures mark a bold leap in scale and considerable human labor. With likely ritual significance, these details are unseen in the small household tokens common at other Neolithic sites.

Were These Haunting Faces Portraits Of Real People?

While some faces appear individualized, particularly in the earlier cache, scholars debate whether the statues represent actual individuals or archetypal figures. Their funerary placement, stylistic uniformity in the later cache, and abstracted bodies hint at symbolic or communal representations rather than literal portraits.

Jean Housen, Wikimedia Commons

Jean Housen, Wikimedia Commons

The Secret Lives Of Reeds, Plaster, And Tar

The statues were crafted from lime plaster applied over reed and twine cores, materials readily available near the Zarqa River. Artisans formed heads, torsos, and limbs separately, then assembled them before modeling. They sometimes finished them with ochre and bitumen to define irises, which shows impressive material ingenuity for 7,200–6,250 BCE.

Mastering Fire Without Metal Tools

To create lime plaster, Neolithic artisans heated limestone to 1112–1652 °F, likely using simple kilns fueled by wood. Without metal tools, this achievement required precise control of temperature and fire. The whole process highlights remarkable technical knowledge and resource coordination over nine millennia ago.

Secretlondon, Wikimedia Commons

Secretlondon, Wikimedia Commons

Sculpting Layer By Painstaking Layer

Artists applied wet plaster in stages onto reed frameworks, building figures layer by layer. Joints were carefully fused during assembly. This delicate process, still visible in CT scans and reconstructions, demonstrates deliberate craftsmanship rather than hurried mass production.

Repairs That Hint At Long-Term Reverence

Evidence of restoration—such as patched cracks or reapplication of finishing materials—suggests the statues held more significance than mere offerings. Their repeated care implies sustained value, perhaps as revered ancestral icons or ceremonial objects maintained over years or generations.

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

Colors Lost To Time

Red ochre for the face and black bitumen outlining eyes created vivid, lifelike expressions that made these statues stand out among other discoveries. Over thousands of years, exposure and burial obscured these colors and left behind haunting hollow shells in archaeological records.

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

Why The Statues Were Not Displayed

These statues were intentionally interred in two subterranean caches beneath abandoned house floors. Scholars suggest they were never meant for long-term display, but rather crafted expressly for burial—possibly as a ceremonial act.

Ludwig Deutsch, Wikimedia Commons

Ludwig Deutsch, Wikimedia Commons

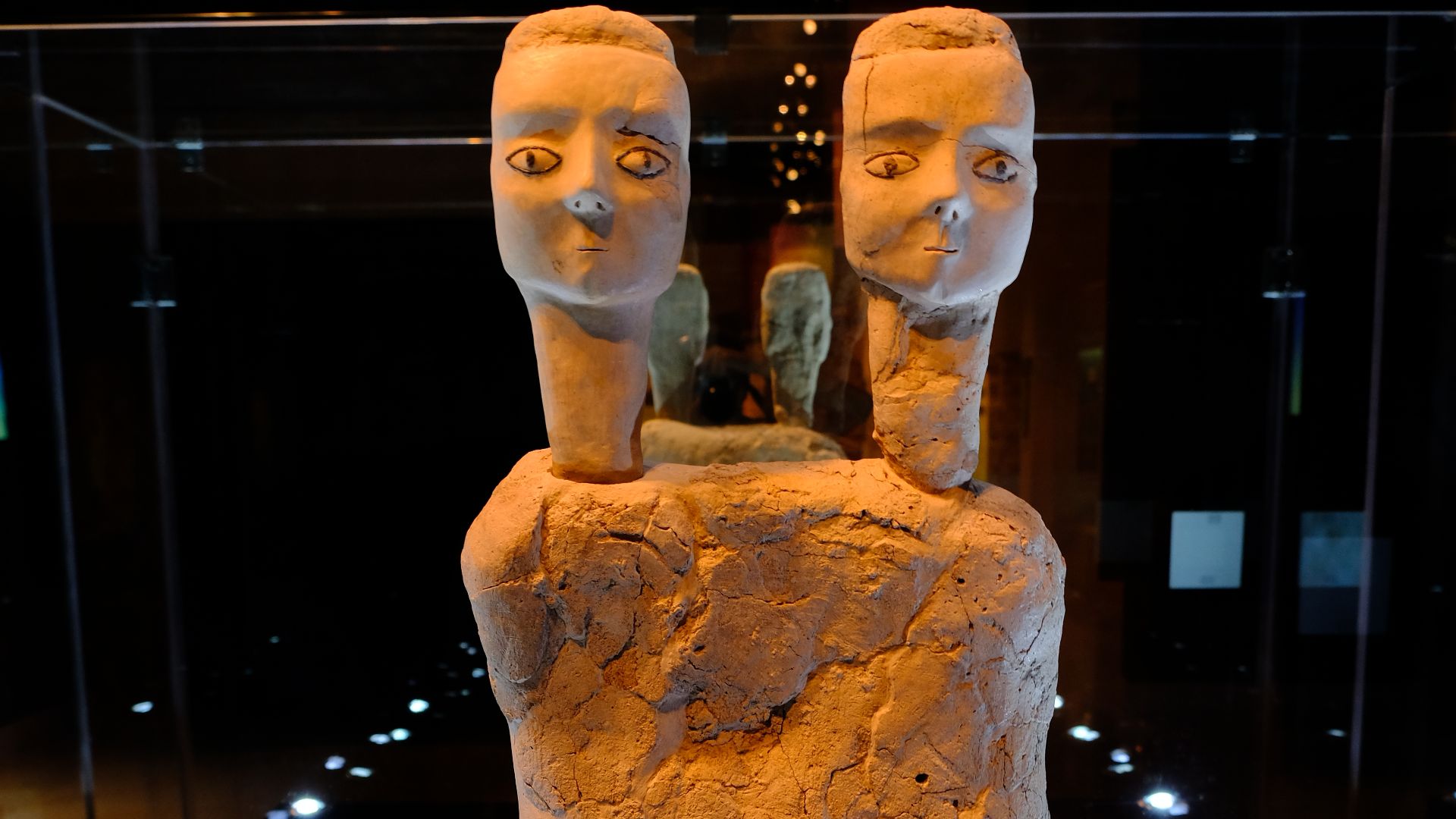

Always In Groups And Never Alone

They appeared in tightly arranged groups: one cache contained 25 items (13 full figures, 12 busts), while the second had seven, including two-headed busts. Their collective deposition hints at a shared ritual context rather than individual expression.

Jean Housen, Wikimedia Commons

Jean Housen, Wikimedia Commons

The Puzzle Of The Two-Headed Figures

Among the later cache’s statues were three enigmatic two-headed busts, an uncommon feature in prehistoric art. Their dual faces may symbolize dualities such as life and death, multiple ancestors, or spiritual transition, but archaeologists remain divided.

Ancestors Or Forgotten Deities

Interpretations of these statues range widely: some scholars propose ancestor veneration, others suggest spiritual guardians or even deities. Their burial mirrored mortuary practices that refer to symbolic life cycles or transitional power.

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

What Deliberate Burial Reveals About Belief

Deliberately burying finely crafted figures indicates complex ideological concepts. The act couples ritual closure with respect, implying these statues were once animate or spiritually potent objects. They perhaps represented a presence that required ceremonial ‘retirement’ through burial.

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

A Society Of Specialists

By around 6500 BCE, Ain Ghazal had evolved beyond a simple agrarian village. Excavation findings of elaborate art, plaster use, and ritual burial suggest the community supported artisans and ritual practitioners. It hints at specialized roles uncommon in early settled societies.

Early Evidence Of Organized Labor And Planning

Creating monumental statues required considerable coordination, from quarrying limestone to firing plaster and assembling reeds. The scale and precision of these tasks indicate planning and group labor, and they point toward organized communal effort that helped this settlement thrive.

AmiraAdel93, Wikimedia Commons

AmiraAdel93, Wikimedia Commons

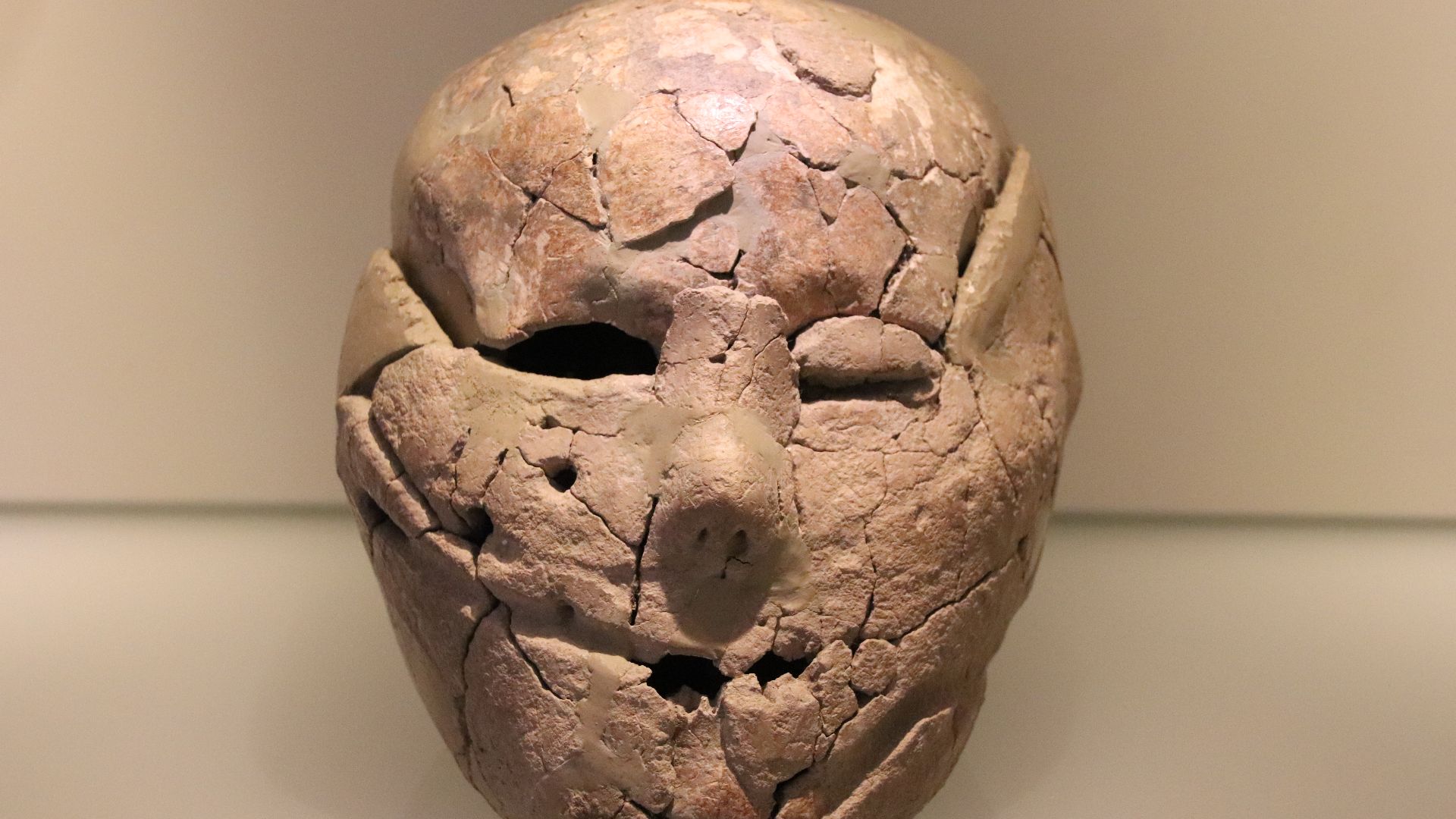

The Possible Rise Of Spiritual Leaders

The ritual interment of statues and plastered skulls suggests individuals may have mediated between the living and supernatural realms. This points to roles akin to priests or spiritual custodians guiding ceremonial life within prehistoric Ain Ghazal. However, more studies are needed to confirm this.

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

Art As Proof Of Social Complexity

Ain Ghazal’s elaborate plaster statues with their diverse symbolic significance and coordinated architectural changes constitute strong evidence of cultural sophistication. These innovations point to a sophisticated society capable of collective expression and symbolic depth far earlier than often assumed.

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

What Do These Creations Say About Identity?

The personalized faces and strategic burial of Ain Ghazal’s statues reflect a social identity rooted in lineage and shared ideology. They shed light on a community consciously defining itself through visual and ceremonial art that still impresses us today.

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

A Shared Tradition Across The Levant

It’s quite astonishing that the Ain Ghazal statues mirror stylistic traits found in contemporary Levantine sites, which suggests a shared visual language or ritual tradition. These echoes point to cultural exchange or common symbolic systems, perhaps as part of growing social networks and spiritual commonalities.

A. Sobkowski, Wikimedia Commons

A. Sobkowski, Wikimedia Commons

Parallels With Jericho’s Plastered Skulls

Preceding the statues by centuries, plastered skulls discovered in nearby Jericho reflect mortuary customs honoring the dead through lifelike modeling. The Ain Ghazal statues seem a further manifestation of this tradition, expanding from skulls to full figures and suggesting evolving rituals around memory and ancestral presence.

Were Ideas Carried Along Ancient Trade Routes?

Material analysis shows Ain Ghazal’s access to non-local resources, including exotic pigments or shells. This implies trade connections, as the community likely participated in broad Neolithic exchange networks. Such networks not only delivered goods but also ideas that shaped ritual and social practices.

Publisher New York Ward, Lock, Wikimedia Commons

Publisher New York Ward, Lock, Wikimedia Commons

Ain Ghazal May Have Been A Spiritual Center

With its burial complexity and ritual structures, Ain Ghazal likely served as a focal ritual hub in the region. It appears to have attracted diverse groups, which signifies an emerging communal identity and spiritual leadership. The location was perhaps a centralized place for worship and ceremonial artistry.

A Community Connected To The Wider Neolithic World

Ain Ghazal’s scale and evidence of mixed origins suggest it was both a magnet for migrants and a central point in regional development. DNA studies and cultural parallels affirm its role in forging communal bonds and bridging Neolithic networks across the Fertile Crescent.

Sarah Murray from Palo Alto, CA, Wikimedia Commons

Sarah Murray from Palo Alto, CA, Wikimedia Commons

Climate Shifts That Reshaped Early Life

Around 6200 BCE, rapid climate change struck the Levant, destabilizing rainfall and agricultural productivity. This shift coincided with the abandonment of many Neolithic settlements, including a dramatic population drop at Ain Ghazal. Environmental stress reshaped prehistoric life and settlement patterns in the region.

Rituals As Desperate Responses To Scarcity

As environmental pressures mounted, communities like Ain Ghazal may have intensified ritual practices and buried statues purposefully to appeal to ancestral or spiritual forces. These acts likely served collective psychological and social needs during periods of resource uncertainty and dwindling agricultural yields.

Struggles Of A Growing Prehistoric Metropolis

At its height (~7000 BCE), Ain Ghazal housed around 3,000 people. However, by ~6500 BCE, the population collapsed to roughly one-sixth its peak within a few generations. The shifting environment and economic collapse left the metropolis vulnerable to disruption.

The Organized Farewell To Ain Ghazal

Rather than abandoned in chaos, the statues and symbol-rich objects were ritually buried in caches—suggesting a ceremonial closure. Such structured final acts signal cultural respect and organized transition, and possibly the end of a societal epoch before the settlement’s glow faded.

Berthold Werner, Wikimedia Commons

Berthold Werner, Wikimedia Commons

A Warning Carved Into Prehistory

The rapid decline of a major Neolithic hub like Ain Ghazal offers a cautionary tale: environmental change can swiftly unravel complex societies. Understanding their collapse accentuates resilience lessons relevant to modern civilization in the face of ecological stress.

Uncovering Hidden Construction Stages

Modern imaging, such as CT scanning, has shown hidden layers of reed cores and plaster joins. These scans enable researchers to map the statues’ internal structure and clarify the builders’ step-by-step sculpting methods. This will help preserve fragile forms and shed light on ancient artistry with modern tools.

Michael Gunther, Wikimedia Commons

Michael Gunther, Wikimedia Commons

Fingerprints Left By Long-Forgotten Sculptors

Analysis of minute details on plaster surfaces suggests individual fingerprints may be embedded in the figures. These tactile marks personalize the statues by linking them directly to their creators. While confirmation is rare, this evidence adds a human connection across 9,000 years by providing glimpses of details from a vanished society.

DNA Revealing Ties To Today’s Populations

Genetic studies at Ain Ghazal show that agricultural practices, including early farming and pottery use, emerged indigenously rather than from invading groups. DNA evidence demonstrates continuity between its inhabitants and later Levantine populations. It highlights cultural development within an enduring ancestral lineage.

jcookfisher, Wikimedia Commons

jcookfisher, Wikimedia Commons

Radar Hints At More Statues Still Underground

Geophysical surveys, especially ground-penetrating radar, suggest the possibility of undiscovered artifacts beneath Ain Ghazal’s surface. Though not yet confirmed, subsurface imaging offers exciting prospects: there may be more statues hidden, waiting to rewrite what we know about Neolithic ritual and art.

The Fragile Battle To Preserve Them

The statues’ lime plaster composition is fragile, sensitive to temperature and humidity changes. After excavation, they needed precise, long-term conservation. They had to be block-lifted and transferred to the Smithsonian to be placed in controlled museum environments. These efforts are essential to maintain their integrity and study their secrets for generations.

Thaler Tamas, Wikimedia Commons

Thaler Tamas, Wikimedia Commons

Were These Statues Art Or Spiritual Technology?

The Ain Ghazal statues blend artistry with ritual. Their crafted faces and monumental scale represent technological mastery and spiritual expression, acting as lasting tools for ceremony or what some scholars term “spiritual technology”. They bridge creative skill and cultural belief, while offering insight into the Neolithic worldview and purposeful symbolism.

Davide Mauro, Wikimedia Commons

Davide Mauro, Wikimedia Commons

How Their Mystery Continues Without Written Records

Without written documentation, the Ain Ghazal statues’ meanings remain speculative. Their monumentality and context spark long-lasting fascination, challenging modern minds to interpret belief systems through symbolic forms alone. The mysteries persist not because they’re unchanged, but because they provoke curiosity across millennia.

Daniel Case, Wikimedia Commons

Daniel Case, Wikimedia Commons

Lessons For Our Own Age Of Environmental Strain

The decline of Ain Ghazal amid the 7,000 BCE climate upheaval highlights an old lesson: societal resilience matters. These ancient burial rituals and collapse show how environmental stress can disrupt even the most complex communities. Their story resonates today and reminds us that adaptation and respect for limits are vital.

Why Ain Ghazal’s Statues Still Speak To Us Today

Nine thousand years later, these statues still show humanity’s eternal urge to memorialize and ask profound questions. They connect contemporary audiences with distant ancestors by bridging past and present through emblematic art and shared human curiosity.

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons