Civilizations Without A Written Trace

Long before Europeans arrived, people lived across North America for thousands of years. They built homes and shaped the land. We call this “prehistoric” because they left no written records—only traces uncovered by digging into the earth.

The First Footsteps In The Americas

Archaeologists believe the first arrivals of humans came over 15,000 years ago from Asia. Some likely crossed a land bridge where Alaska and Siberia once connected, while others traveled by boat along the Pacific coast. Their stone tools prove they reached far into the continent.

Rakshitha bhat, Wikimedia Commons

Rakshitha bhat, Wikimedia Commons

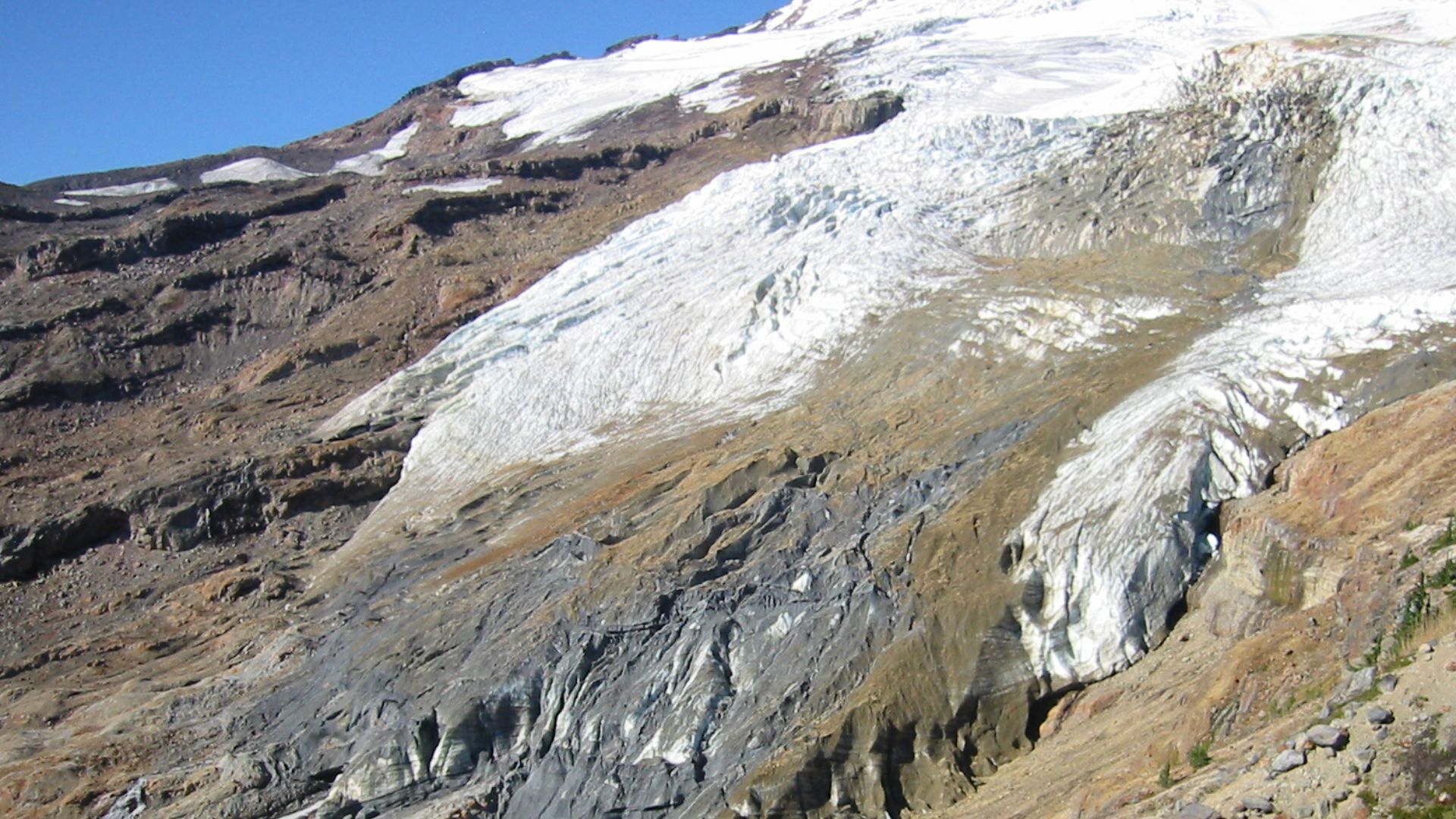

Terrains Of The Ice Age

When those first people arrived, the world looked very different. Massive glaciers covered much of the north, and grasslands stretched across what is now the central United States. Strange animals like mammoths and giant sloths roamed. Scientists have reconstructed these environments by studying ancient pollen and animal remains.

Walter Siegmund, Wikimedia Commons

Walter Siegmund, Wikimedia Commons

Hunting The Megafauna

Early families faced creatures much larger than anything alive today. They crafted sharp stone spear points, known as Clovis points, to take down mammoths and other giants. Sites in places like New Mexico still reveal piles of bones, showing how dangerous yet rewarding these hunts were.

Mauricio Antón, Wikimedia Commons

Mauricio Antón, Wikimedia Commons

Life After The Extinctions

Over time, many of those giant animals died out. People had to adapt. Instead of hunting mammoths, they turned to deer, rabbits, fish, nuts, and seeds. Archaeologists even found grinding stones coated with traces of ancient plants—evidence of new ways to feed communities.

Stone Tools And New Technologies

However, not every tool was made for hunting. Clothing was stitched using tools made from bone. Antler was sometimes carved into tools for gathering food, while sharp flakes of volcanic glass became cutting edges. These materials fulfilled everyday needs in ways that were both practical and resourceful.

Fire As A Tool Of Survival

Fire gave warmth, light, and cooked meals, but it also reshaped the land. Charcoal layers in ancient soils show that deliberate fires were set to clear vegetation. Controlled fire encouraged fresh plants to sprout, which in turn drew grazing animals back into hunting range. It’s now known as slash-and-burn agriculture.

Kenneth Hawes, Wikimedia Commons

Kenneth Hawes, Wikimedia Commons

Shelters Of Early North America

Living outdoors year-round wasn’t practical, so shelters were built. In some places, they used caves or rock overhangs. Elsewhere, they dug pit houses into the ground, which stayed warmer in winter. These outlines of posts and hearths remind us that housing solutions varied as widely as the climates people faced.

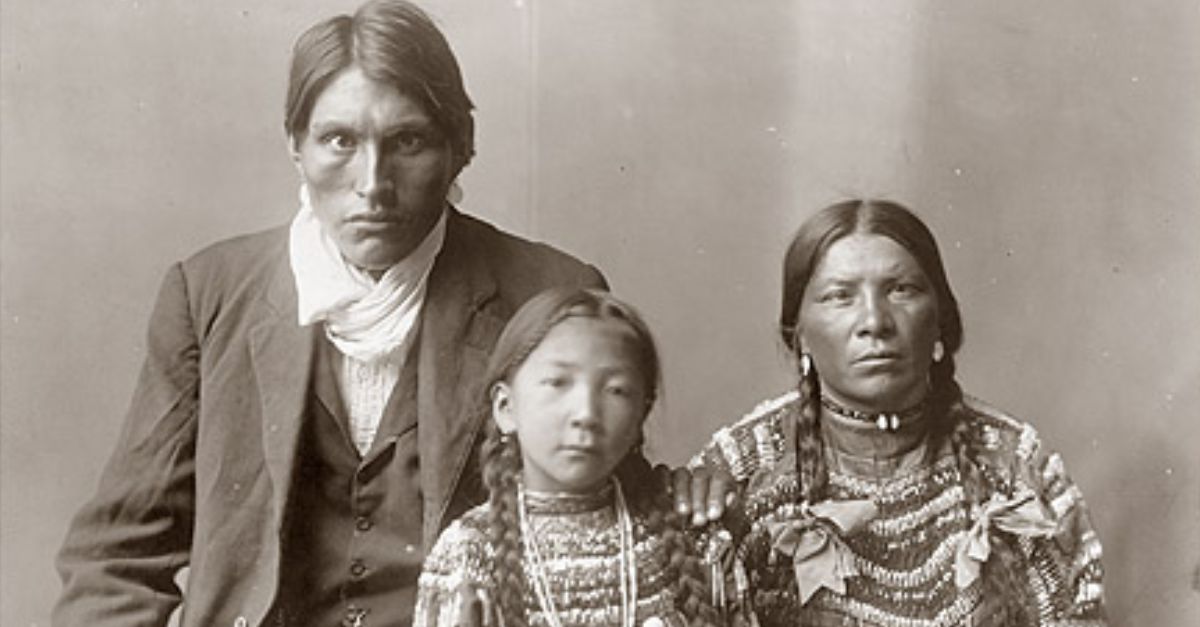

Rudolf Cronau, Wikimedia Commons

Rudolf Cronau, Wikimedia Commons

Rivers And Seas As Highways

Waterways were essential to survival. Rivers and coastlines provided everything from food to easy travel routes. Canoe fragments and shell middens—huge piles of discarded shells—prove how important these environments were. They acted like highways, linking different groups and supporting life for thousands of years.

Cleveland Museum of Art, CC0, Wikimedia Commons

Cleveland Museum of Art, CC0, Wikimedia Commons

The Beginnings Of Plant Domestication

Wild plants slowly became crops. Excavations have found ancient garden plots and charred seeds that still held their shape even after thousands of years in the ground. In the eastern woodlands, sunflower and goosefoot were cultivated for food long before maize arrived from Mexico.

Bruce Fritz, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Wikimedia Commons

Bruce Fritz, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Wikimedia Commons

Farming Villages Take Shape

With crops came permanence. Families no longer moved seasonally but clustered in villages with fields nearby. Storage pits dug into the ground preserved harvests through winter. One site in Illinois held hundreds of these pits, each carefully sealed against rodents and moisture.

The Archaic Period In Transition

In North American Archaeology, the term “Archaic Period” is used for the era after the Ice Age, roughly 8000 to 1000 BCE. During this era, people experimented with many strategies—hunting smaller animals, fishing, and planting crops. Artifacts from this time also reveal increasing diversity in daily life across the continent.

Brian Stansberry (photographer), Wikimedia Commons

Brian Stansberry (photographer), Wikimedia Commons

Mounds And Monuments Of Earth

Some communities built huge mounds from basket after basket of soil. Poverty Point is one of the largest and most complex earthworks of its time in North America. These weren’t just homesites—they served ceremonial and social functions, where thousands of people gathered for rituals.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/15308454@N06/ Kniemla, Wikimedia Commons

https://www.flickr.com/photos/15308454@N06/ Kniemla, Wikimedia Commons

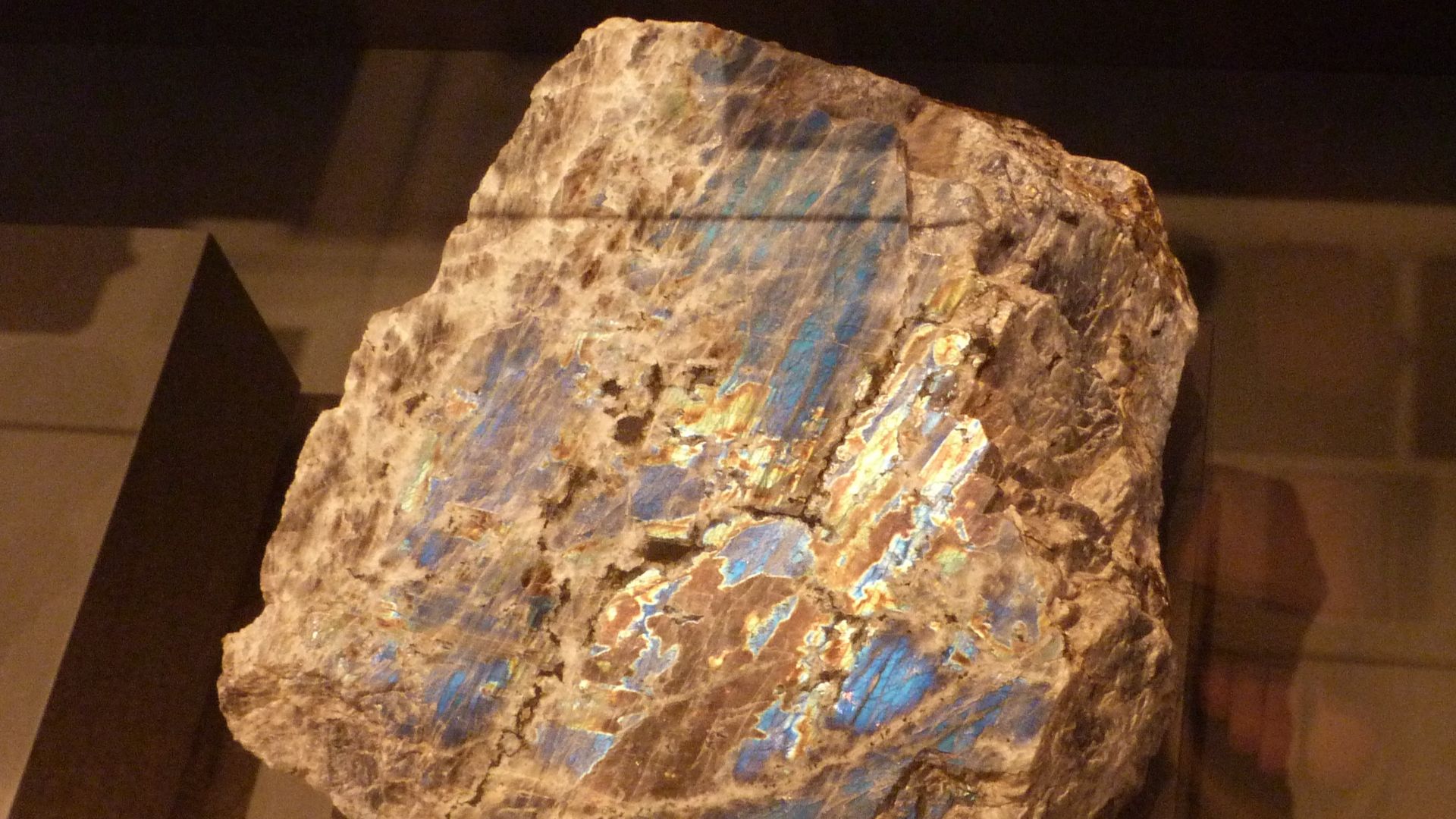

Networks Of Trade Without Wheels

Trading copper from the Great Lakes for shells from the Gulf Coast happened without carts or wagons. These trade routes are matched by the mineral “fingerprints” of artifacts to their exact geological sources. Such networks connected groups across North America and spread cultural traditions.

S. Rae from Scotland, UK, Wikimedia Commons

S. Rae from Scotland, UK, Wikimedia Commons

Puebloan Architecture And Roads

In the American Southwest, ancestral Puebloans built multi-room towns from stone and adobe. Chaco Canyon became a central hub, with long, straight roads connecting far-off communities. At the center of village life were kivas, underground rooms used for all sorts of gatherings.

National Park Service (United States), Wikimedia Commons

National Park Service (United States), Wikimedia Commons

Life On The Plains Before Horses

Long before horses arrived, inhabitants on the Great Plains relied on bison. Families used clever drive lines of stone or brush to funnel herds toward hunters. The remains of tipis—circles of stones left from tent bases—still mark where these mobile groups once lived.

Mississippian Cities And Cahokia

Cahokia, near present-day St. Louis, was the largest city north of Mexico a thousand years ago. It held tens of thousands of people and enormous mounds, including one taller than a ten-story building. Excavations reveal houses and complex farming that supported urban life.

Thank You (24 Millions ) views, Wikimedia Commons

Thank You (24 Millions ) views, Wikimedia Commons

Arctic Survival In Ice And Snow

Life in the Arctic demanded special skills. The ancestors of modern Inuit peoples developed sophisticated technologies like snow houses and skin boats to survive the harsh Arctic environment. Even umiaks, large open boats made of skins, allowed families to travel the icy seas. These inventions made survival possible.

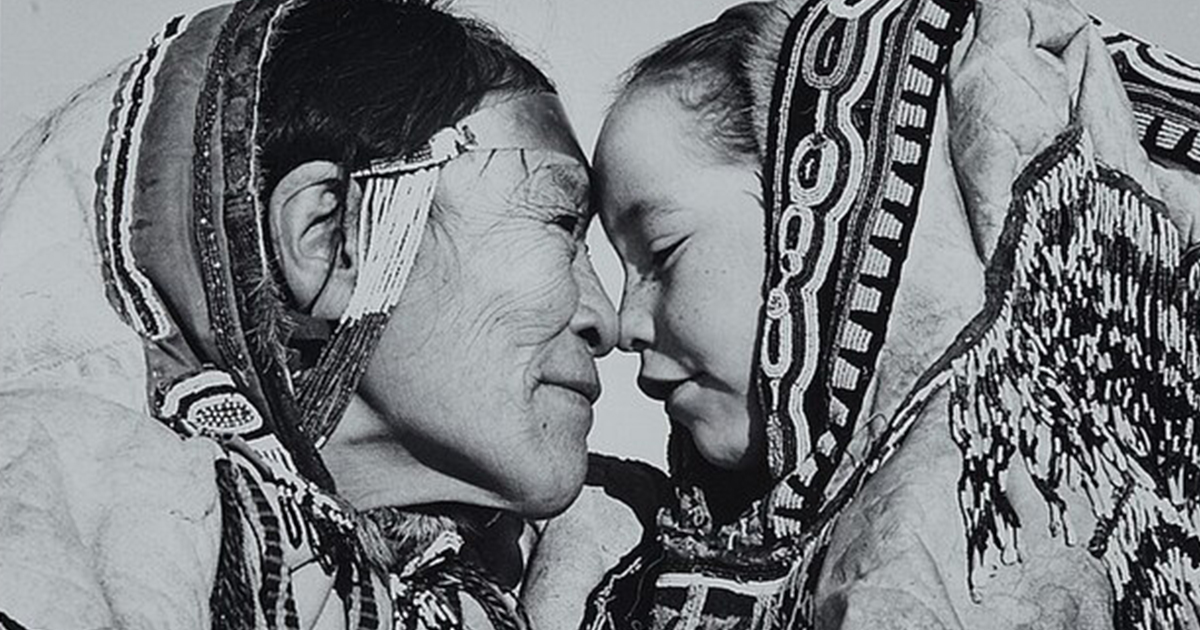

Asahel Curtis, Wikimedia Commons

Asahel Curtis, Wikimedia Commons

Northwest Coast Societies Of Salmon And Totems

Along the Pacific Northwest coast, salmon runs were so plentiful that communities built permanent wooden villages. Totem poles carved with animals told stories of families and ancestors. Archaeologists found huge cedar plank houses, some large enough to hold dozens of people under one roof.

Jeremy Keith from Brighton & Hove, United Kingdom, Wikimedia Commons

Jeremy Keith from Brighton & Hove, United Kingdom, Wikimedia Commons

Resilient Foragers Of The Great Basin

The desert may look empty, but ancient families made it work. They moved with the seasons, gathering what the land offered. In dry caves, baskets and sandals have been seen that are so well preserved that you can still see the woven patterns and faint fingerprints.

Earth's beauty internet site, Wikimedia Commons

Earth's beauty internet site, Wikimedia Commons

Desert Farmers And Hohokam Canals

In the Sonoran Desert, the Hohokam created hundreds of miles of irrigation canals. These channels watered crops from maize to squash fields. Traces of the canals still run across Arizona today, showing how farming thrived in places where rain rarely reached the soil.

Art On Stone Walls

Across deserts and canyons, carvings and paintings on the rocks show animals, abstract symbols, and more. These petroglyphs and pictographs may have marked hunting grounds or told stories. Their exact meanings remain unknown, but they prove creativity flourished long before written language.

The original uploader was Camerafiend at English Wikipedia., Wikimedia Commons

The original uploader was Camerafiend at English Wikipedia., Wikimedia Commons

Burials And Memory Of The Dead

The belief system can be found through burials. Some communities built large mounds to cover the dead (some with jewelry), while others cremated remains. These practices suggest death was never just an ending for them—it carried social and spiritual importance within each community.

Nabokov (talk) Required attribution is:

Nabokov (talk) Required attribution is:

Cultural Traditions That Still Continue Today

Practices that began in prehistoric times never fully disappeared. Farming methods, basket weaving, and ceremonial gatherings still exist in many Indigenous communities. Archaeology helps connect ancient tools and structures to living traditions that carry it forward in daily life.

Chukwukajustice, Wikimedia Commons

Chukwukajustice, Wikimedia Commons

A World Thriving Without Writing

Everything we’ve uncovered—from tools to cities—shows that prehistoric North Americans shaped complex lives without writing anything down. Their achievements weren’t recorded in books, but they’re written into the land itself. What survives in the ground tells just part of the story.

Profberger (talk) (Uploads), Wikimedia Commons

Profberger (talk) (Uploads), Wikimedia Commons