Japan’s First People

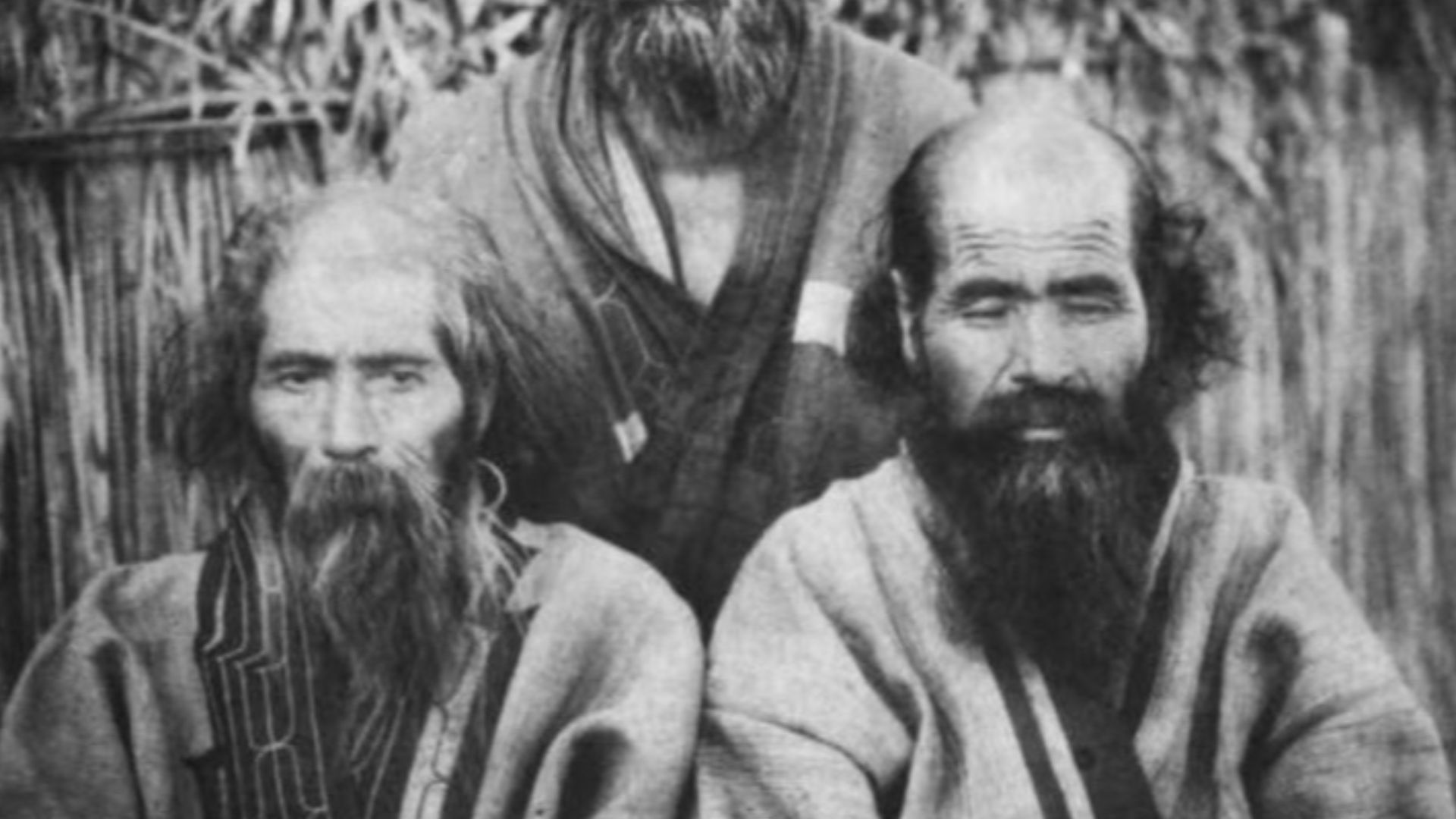

The Ainu are an Indigenous people who have lived for centuries in northern Japan and parts of eastern Russia, especially Hokkaido, Sakhalin, and the Kuril Islands. Known for their rich traditions, animist beliefs, and resilience in the face of assimilation, they are one of Japan's most distinct ethnic groups.

The Meaning Behind The Name Ainu

In the Ainu language, the word "Ainu" simply means “human,” especially in contrast to divine beings known as kamuy. Historically, Ainu people also referred to themselves as “Utari”, meaning "comrades”. The term “Ainu” became commonly used in the 19th century, but its roots appear in 16th-century European records.

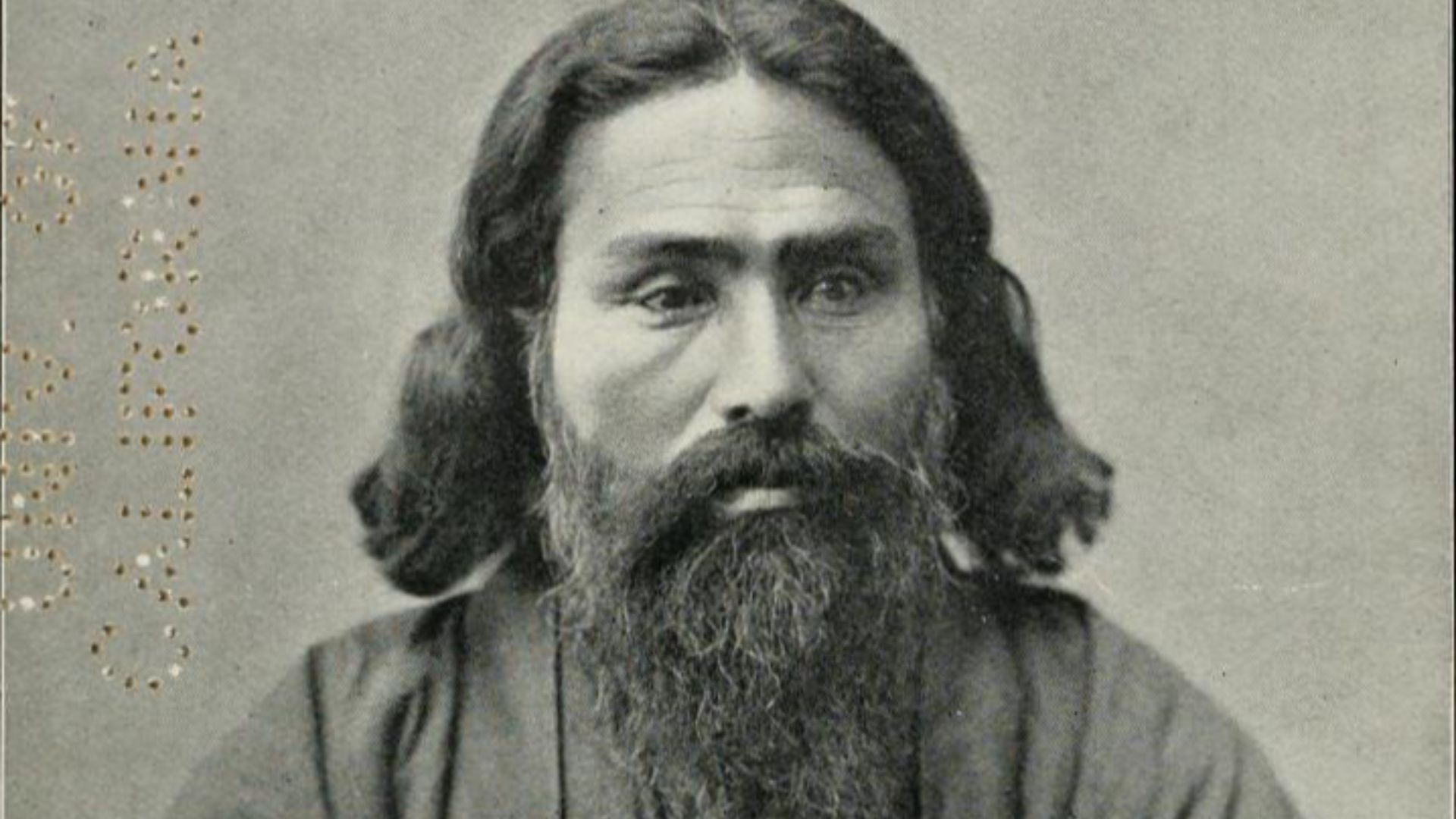

Murase Yoshinori, Wikimedia Commons

Murase Yoshinori, Wikimedia Commons

Ancestral Homeland Of Ainu Mosir

The Ainu call their traditional homeland “Ainu Mosir,” which translates to “land of the Ainu”. This includes parts of modern-day Hokkaido, Sakhalin, and the Kuril Islands. Historically, this area was referred to as “Ezochi” in Japanese texts.

Adrien-Hubert Brue, Wikimedia Commons

Adrien-Hubert Brue, Wikimedia Commons

Once Known As The Emishi

Before being called Ainu, their ancestors were known to the Japanese as “Emishi”. These people lived in northern Honshu and resisted Yamato expansion during the early centuries CE. Over time, they were pushed further north into Hokkaido and beyond.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Related To Other Indigenous Cultures

The Ainu are genetically and culturally linked to the ancient Jomon peoples of Japan. They also share cultural and linguistic ties with the Nivkh and Uilta peoples of Sakhalin.

Forced Assimilation Policies

From the 18th century onward, Japanese governments imposed assimilation policies on the Ainu. These included bans on the Ainu language and religious practices, and the forced relocation of Ainu from ancestral lands.

Torbenbrinker, Wikimedia Commons

Torbenbrinker, Wikimedia Commons

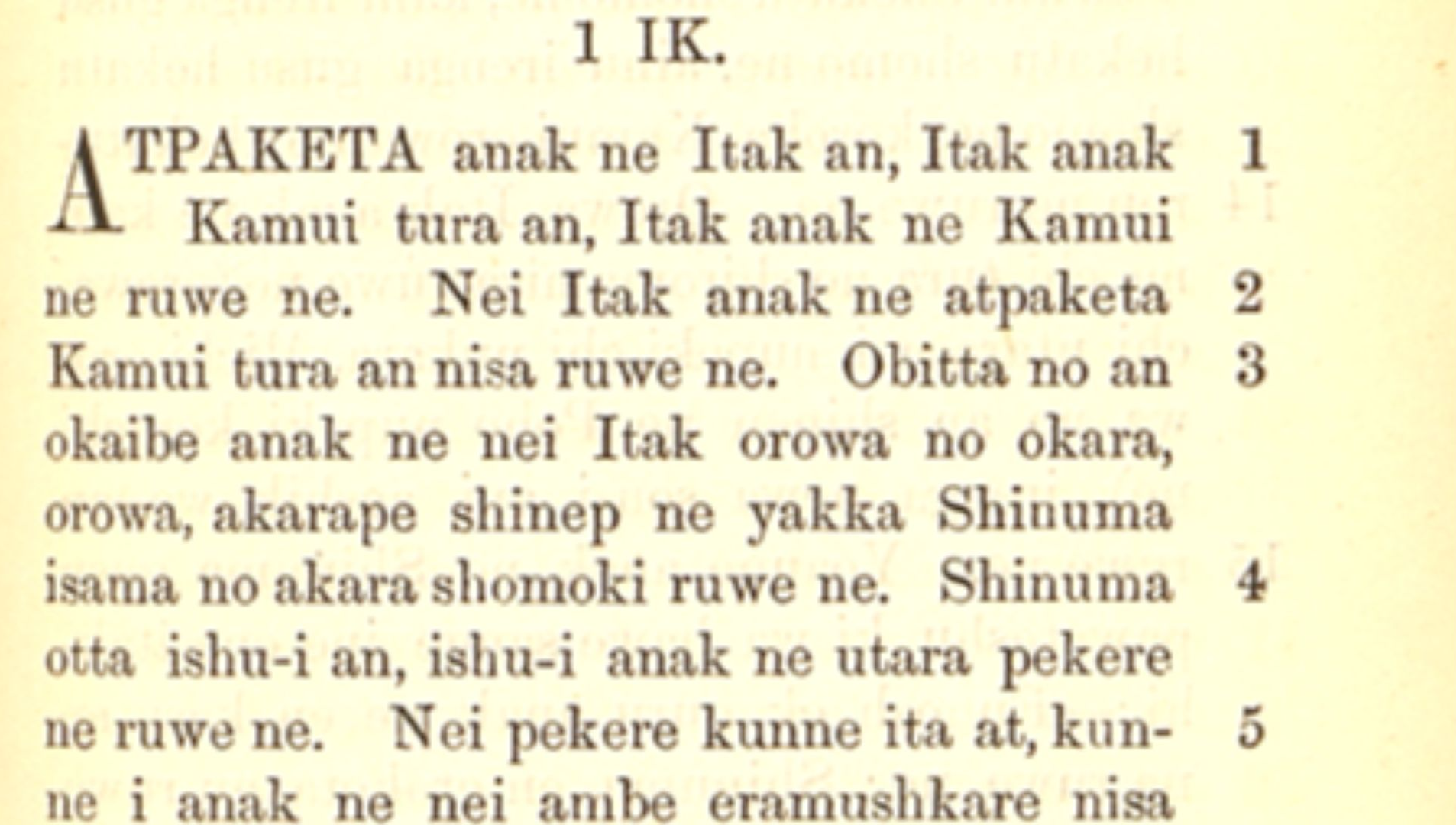

The Ainu Language Is Nearly Extinct

The Ainu language is a language isolate with no known relatives. By 2008, fewer than 100 native speakers remained, though revitalization efforts are ongoing. The language has traditionally been passed down orally, especially through epic poetry called yukar.

John Batchelor (missionary), Wikimedia Commons

John Batchelor (missionary), Wikimedia Commons

A Unique Religion Centered On Nature

Traditional Ainu belief is animist, with spirits called kamuy believed to inhabit all things in nature. Key deities include the hearth goddess Kamuy-huci and the mountain god Kim-un-kamuy. Ceremonies often involve offerings, ritual dancing, and the use of sacred shaved sticks called inau.

National Museum of Denmark from Denmark, Wikimedia Commons

National Museum of Denmark from Denmark, Wikimedia Commons

The Bear Is Sacred

Bears hold a special place in Ainu belief, and are seen as messengers from the gods. The Ainu raised bear cubs in their homes before sacrificing them in the Iomante ceremony to release their spirits. This ritual symbolized respect and ensured the return of the bear’s spirit to the divine world.

Traditional Homes Called “Chise”

The Ainu lived in houses called chise, constructed from natural materials like bark and grass. These homes had a sacred eastern window, the rorun-puyar, through which spirits were believed to travel.

Organized Into Villages Called Kotan

Ainu communities were traditionally small and organized into villages called kotan. Each kotan was often situated near rivers to ensure access to salmon, their staple food. In the modern era, forced relocations disrupted this traditional structure.

663highland, Wikimedia Commons

663highland, Wikimedia Commons

Rich Oral Traditions

Without a written language, the Ainu developed a strong oral culture. They passed down epic tales (yukar) and folktales (uwepeker) through generations. These were performed at community gatherings that could last hours or even days.

David Ooms from Belgium, Wikimedia Commons

David Ooms from Belgium, Wikimedia Commons

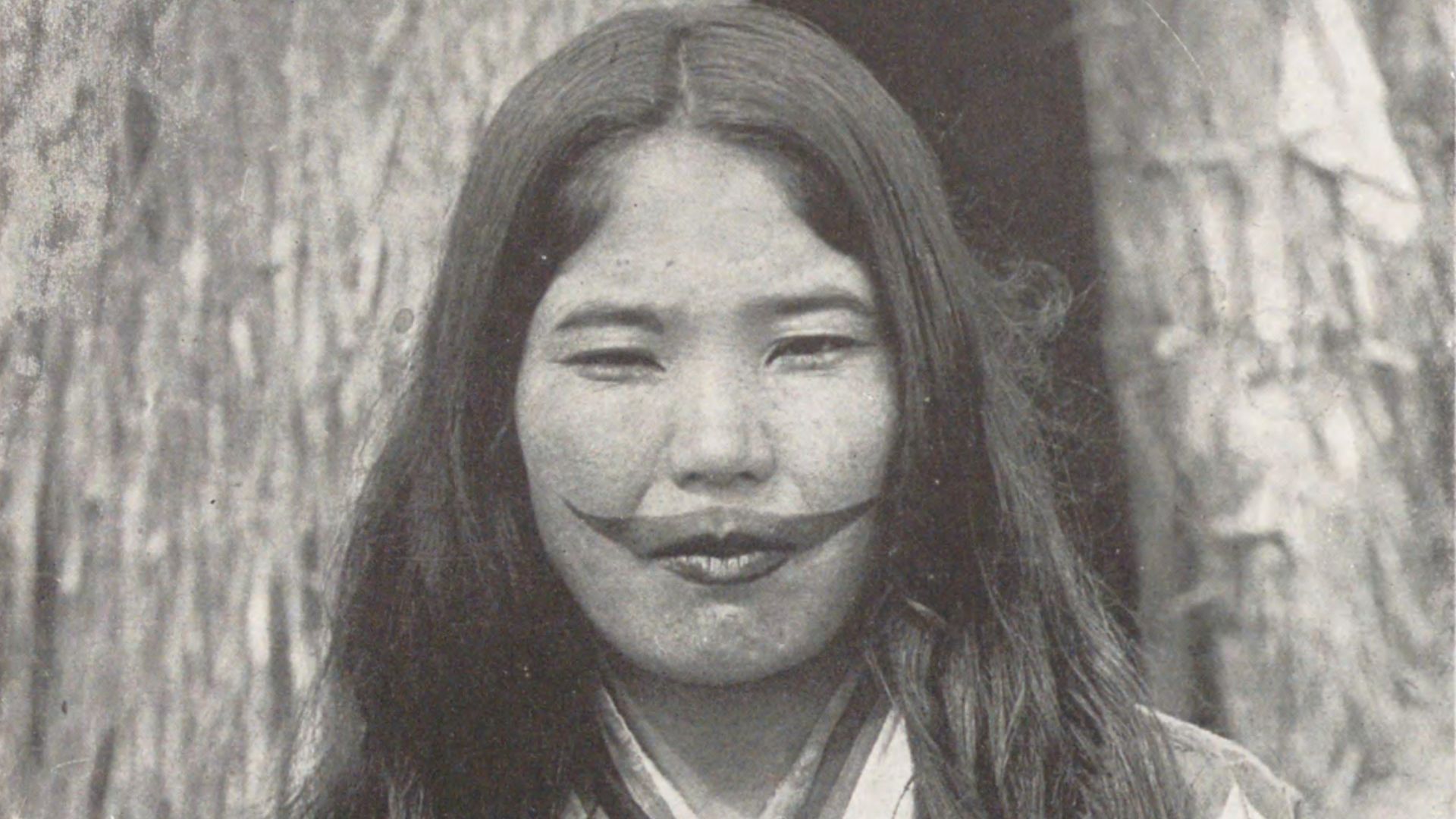

Distinctive Clothing And Tattoos

Traditional Ainu clothing was made from elm bark fiber and embroidered with unique patterns. Women also adorned themselves with mouth and arm tattoos, believed to protect against evil spirits. Both men and women valued earrings and beaded necklaces as important cultural items.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unique Marriage Customs

Marriage arrangements were often made by parents or go-betweens. A traditional engagement proposal involved a man presenting a bowl of rice to a woman. If she ate from the bowl, the proposal was accepted.

munechika tanaka, Wikimedia Commons

munechika tanaka, Wikimedia Commons

Birth And Naming Rituals

Ainu babies were initially given “dirty” temporary names like “small excrement” to ward off negative spirits. Permanent names were assigned later, often based on personality or events. Babies were also given herbal decoctions before nursing to purge impurities.

Charles Carpenter (Field Museum), Wikimedia Commons

Charles Carpenter (Field Museum), Wikimedia Commons

Coming Of Age With Tattoos

Girls received mouth tattoos starting around age 12, completed by age 15 or 16. Tattoos marked adulthood and readiness for marriage. Boys underwent rituals including proper hair styling and wearing specific clothing.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

A Cuisine Rooted In Survival

Ainu cuisine relied on hunted animals, gathered roots, and cultivated millet. Salmon, known as kamuy chep, or "god’s fish," was especially significant. Dishes were typically boiled or roasted, as raw food was traditionally avoided.

Expert Hunters And Fishermen

The Ainu hunted bears, deer, and foxes using poisoned arrows and spears. They also trapped animals with spring-loaded devices and used dogs during hunts. Fishing was done with spears, nets, and traps in family- or village-owned river territories.

Hans Drijer, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Hans Drijer, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Poisoned Arrows Were Traditional

The Ainu used aconite root to create a harmful poison called surku. This poison was applied to arrow tips and made more potent with secret family recipes. The arrows were used for hunting large game like bears and deer.

Sacred Dance And Song

Ritual dances and songs were central to Ainu ceremonies. Dances often mimicked the movements of animals, including the bear. Music and storytelling reinforced spiritual beliefs and were also used in festivals and daily life.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Ceremonial Rituals Honored Nature

The Ainu held seasonal rituals to honor and send back kamuy spirits. Sacred altars called nusa were decorated with inau and animal skulls. These ceremonies emphasized gratitude for nature’s gifts and promoted balance between the human and spiritual worlds.

Japanexperterna.se, Wikimedia Commons

Japanexperterna.se, Wikimedia Commons

The Iomante Bear Ceremony

The Iomante, or bear-sending ceremony, involved raising a cub like a family member. Once matured, it was sacrificed with great ritual to release its spirit. This controversial practice was banned in 1955 but later revived as a cultural festival.

Fire Was Spiritually Central

The hearth and its deity, Kamuy Fuchi, played a vital role in everyday life. Prayers and offerings were made through the fire, especially in funerals. The hearth also served as a bridge between the living and the spiritual world.

Funerary Traditions Reflected Spiritual Beliefs

The Ainu buried those who passed with personal items broken to release their spirits. Funeral rites included prayers, fire offerings, and laments to aid the soul’s journey. In cases of unnatural unaliving, villagers openly scolded the gods.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Orientation Of Homes And Graves Had Meaning

Traditional chise homes and graves were oriented toward the rising sun or rivers. This practice reflected spiritual symbolism, such as respect for deities entering through sacred eastern windows. Grave orientation varied by region, suggesting local beliefs.

No machine-readable author provided. Hno3 assumed (based on copyright claims)., Wikimedia Commons

No machine-readable author provided. Hno3 assumed (based on copyright claims)., Wikimedia Commons

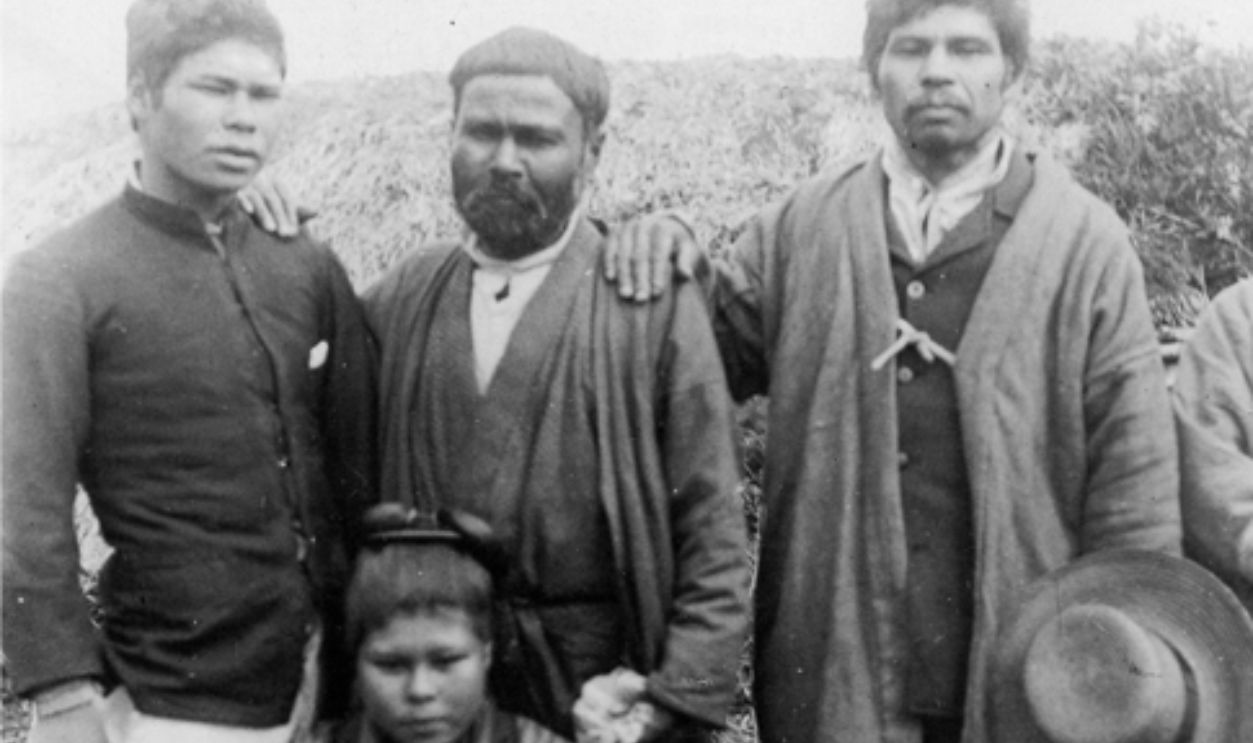

Japanese Colonization Impacted Ainu Life

During the Meiji era, the Japanese government took Ainu land for development and settlement. Traditional hunting and fishing were restricted, and religious practices like tattooing were banned. The Ainu were labeled "former aborigines" and denied Indigenous rights.

Uchida Kuichi, Wikimedia Commons

Uchida Kuichi, Wikimedia Commons

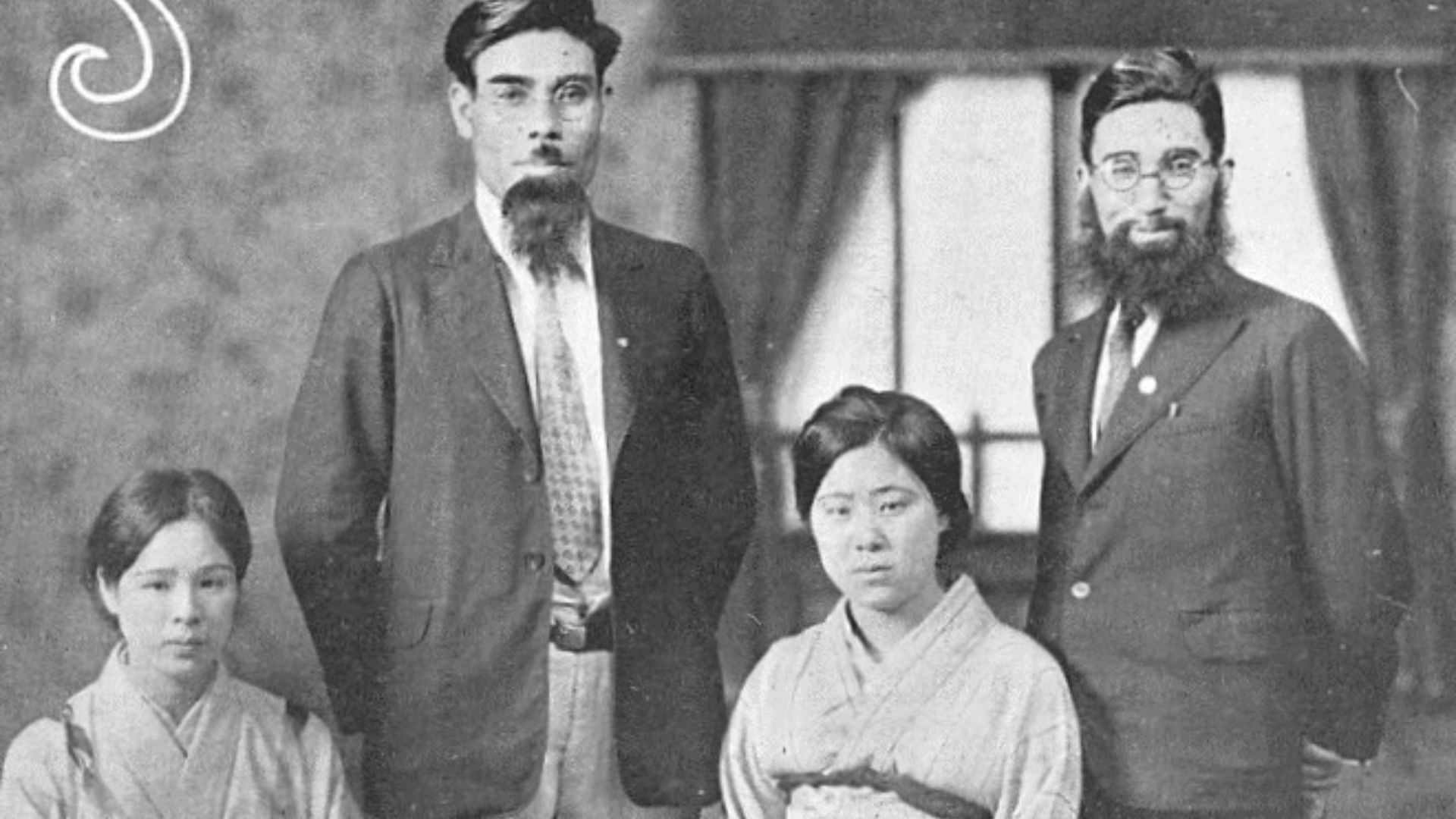

Legal Recognition Came Slowly

In 1997, the Japanese government officially recognized the Ainu as an Indigenous people. A 2008 resolution and a 2019 law further reinforced their status. However, cultural discrimination and economic inequality remain ongoing challenges.

Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney, Wikimedia Commons

Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney, Wikimedia Commons

The Nibutani Dam Case Was Pivotal

A court case in the 1990s centered on land seized for the Nibutani Dam. Two Ainu men, Tadashi Kaizawa and Shigeru Kayano, challenged the expropriation. The court recognized the Ainu as an Indigenous people and acknowledged historical injustices.

Private First Class Hechuan, Wikimedia Commons

Private First Class Hechuan, Wikimedia Commons

Museums Now Promote Ainu Heritage

Institutions like the National Ainu Museum in Shiraoi preserve and promote Ainu culture. Exhibits include traditional crafts, music, language, and ceremonial practices.

The Language Is Being Revitalized

Though nearly extinct, the Ainu language is being taught again through schools and community centers. Activists like Shigeru Kayano led early efforts to document and revive it.

Ainu Religion Is Animist And Polytheistic

The Ainu recognize many gods in nature, from bears to sea creatures to fire. There are no formal priests; village leaders conduct rituals. Offerings include sake, food, and inau, crafted sticks with spiritual significance.

Torii Ryuzo (Torii Ryuzo)(1870-1953, Wikimedia Commons

Torii Ryuzo (Torii Ryuzo)(1870-1953, Wikimedia Commons

Political Advocacy Has Grown

In 2012, activists launched the Ainu Party to push for equal rights. The group seeks greater inclusion in national policy and protections for Ainu culture. Their emergence marks a political shift toward Indigenous representation in Japan.

Torii Ryuzo (1870-1953, Wikimedia Commons

Torii Ryuzo (1870-1953, Wikimedia Commons

Ainu Crafts Hold Spiritual Value

Ainu artisans create garments, tools, and jewelry believed to carry spiritual power. Patterns on robes and carvings often represent protection or blessings. Traditional items are made with deep respect, as they are thought to embody kamuy spirits.

Tokyo National Museum, Wikimedia Commons

Tokyo National Museum, Wikimedia Commons

The Role Of Women Was Vital

Ainu women were tattoo artists, spiritual caretakers, and oral historians. They prepared medicinal herbs, sang epic poems, and cared for bear cubs in rituals. Despite assimilation, many modern Ainu women continue to revive these traditions.

Japanexperterna.se, Wikimedia Commons

Japanexperterna.se, Wikimedia Commons

Intermarriage Was A Strategy

Many Ainu encouraged intermarriage with Japanese people to reduce discrimination. As a result, many Japanese people today have Ainu ancestry but are unaware of it. This makes population estimates difficult and has led to cultural invisibility.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Discrimination Still Persists

Even today, Ainu people face economic and social inequality. They have lower average incomes, higher welfare rates, and lower educational attainment than the general Japanese population. Activists continue to press for policy change and recognition.

See page for author, Wikimedia Commons

See page for author, Wikimedia Commons

Regional Differences Shaped Culture

Different subgroups of Ainu existed in Sakhalin, Hokkaido, and the Kuril Islands. Some maintained distinct dialects and traditions shaped by local environments. Many of these communities are now extinct due to battles, relocation, and assimilation.

Lyakhovets Sergey, Wikimedia Commons

Lyakhovets Sergey, Wikimedia Commons

Ainu Populations Live Across Japan And Russia

As of 2023, around 11,450 Ainu were officially surveyed in Hokkaido, with unofficial estimates much higher. About 300 Ainu live in parts of eastern Russia. Tokyo is also home to a growing urban Ainu community.

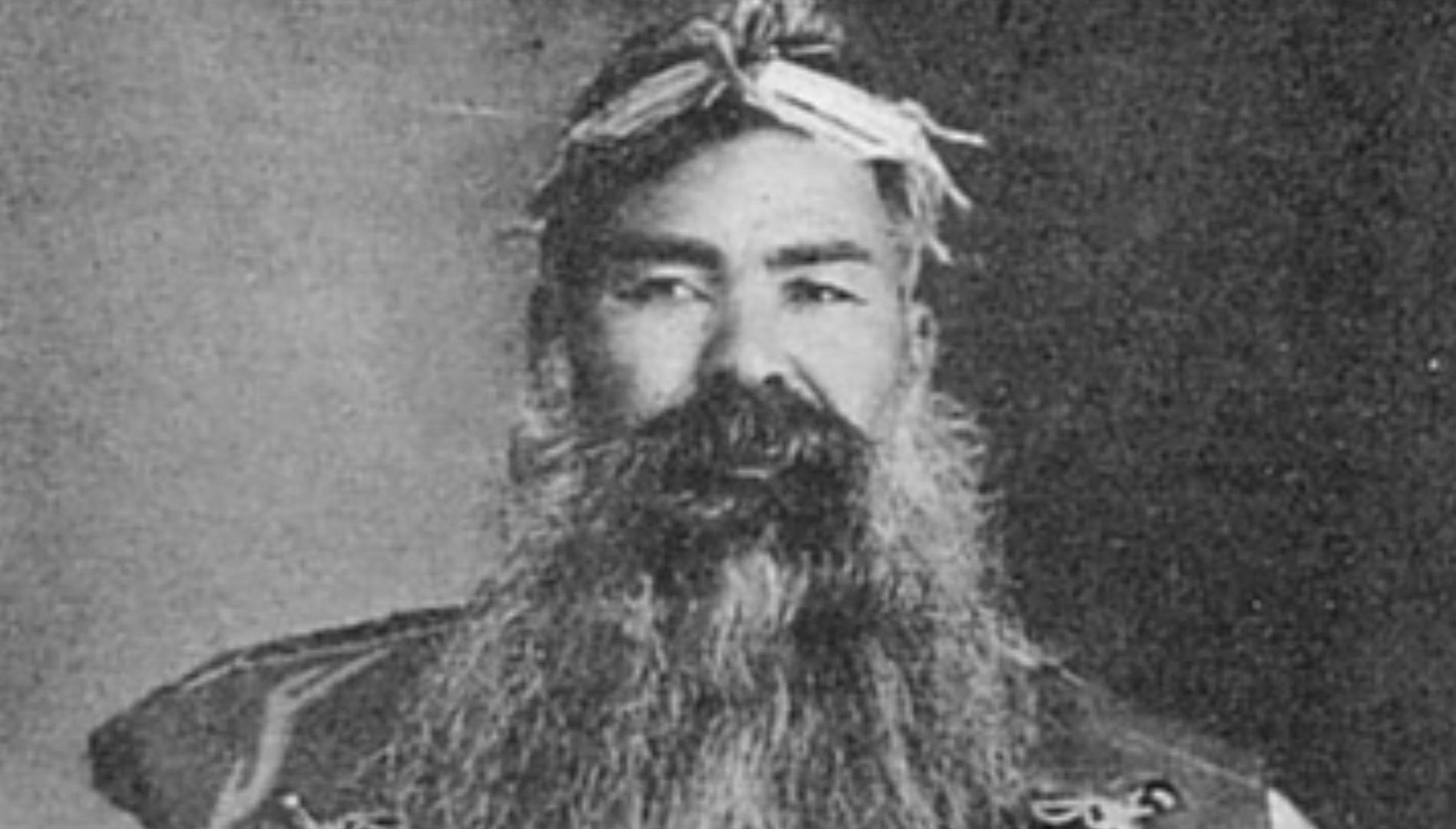

John Batchelor (1854-1944), Wikimedia Commons

John Batchelor (1854-1944), Wikimedia Commons

Ainu Inspired Art Appears In Pop Culture

Ainu culture has inspired films, anime, and video games like Golden Kamuy and Ōkami. While sometimes romanticized, these portrayals have helped raise awareness.

Yves Tennevin, Wikimedia Commons

Yves Tennevin, Wikimedia Commons

International Partnerships Are Emerging

Ainu leaders have formed connections with other Indigenous groups, including the Sámi of northern Europe. They share experiences of colonization, revitalization, and cultural diplomacy.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

You May Also Like:

Photos Of The Sámi, The Only Indigenous Tribe In Europe

Things Americans Might Find Strange In Japan

Life Inside Japan’s Eerie Doll Village

Source: 1