The Roman Empire Might Have Made It To Texas

Walk into a Goodwill on Far West Boulevard in Austin, Texas, and you expect bric-a-brac—not the marble gaze of ancient Rome. Yet that’s exactly what confronted Austin antiques hunter Laura Young in 2018: a 52-pound marble head resting under a table, a yellow sticker on its cheek that read $34.99. She bought it, buckled it into her car, and drove home stunned.

First Impressions: “Clearly Antique—Clearly Old”

Young deals in vintage objects; patina and tool marks speak to her. The bust’s weathered surface, chisel traces, and weight screamed marble, not plaster. At home, a quick image search for “Roman bust” confirmed her hunch: stylistically, “they look a lot like my guy.” The mystery had begun—and with it, a modern odyssey through museums and archives.

Woman buys a 2000-year-old roman bust for $35 at thrift shop, WFAA

Woman buys a 2000-year-old roman bust for $35 at thrift shop, WFAA

The Price Tag Versus The Provenance

The absurdity of a millennia-old sculpture marked at $34.99 hints at the chaotic afterlives of ancient art. Objects slip from palaces to private homes, from battlefields to basements, and sometimes—astonishingly—onto thrift-store shelves. In this case, that sticker masked a backstory stretching from a 19th-century Bavarian prince’s collection to the devastation of World War II.

Woman buys a 2000-year-old roman bust for $35 at thrift shop, WFAA

Woman buys a 2000-year-old roman bust for $35 at thrift shop, WFAA

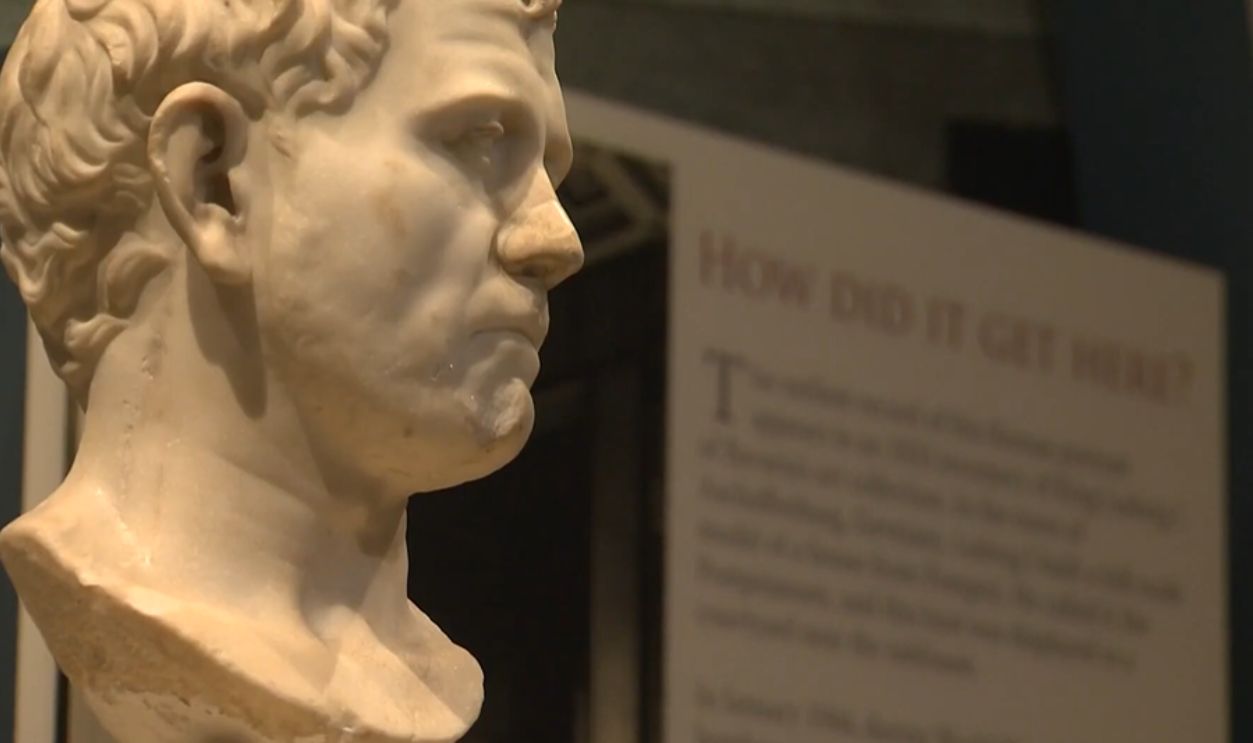

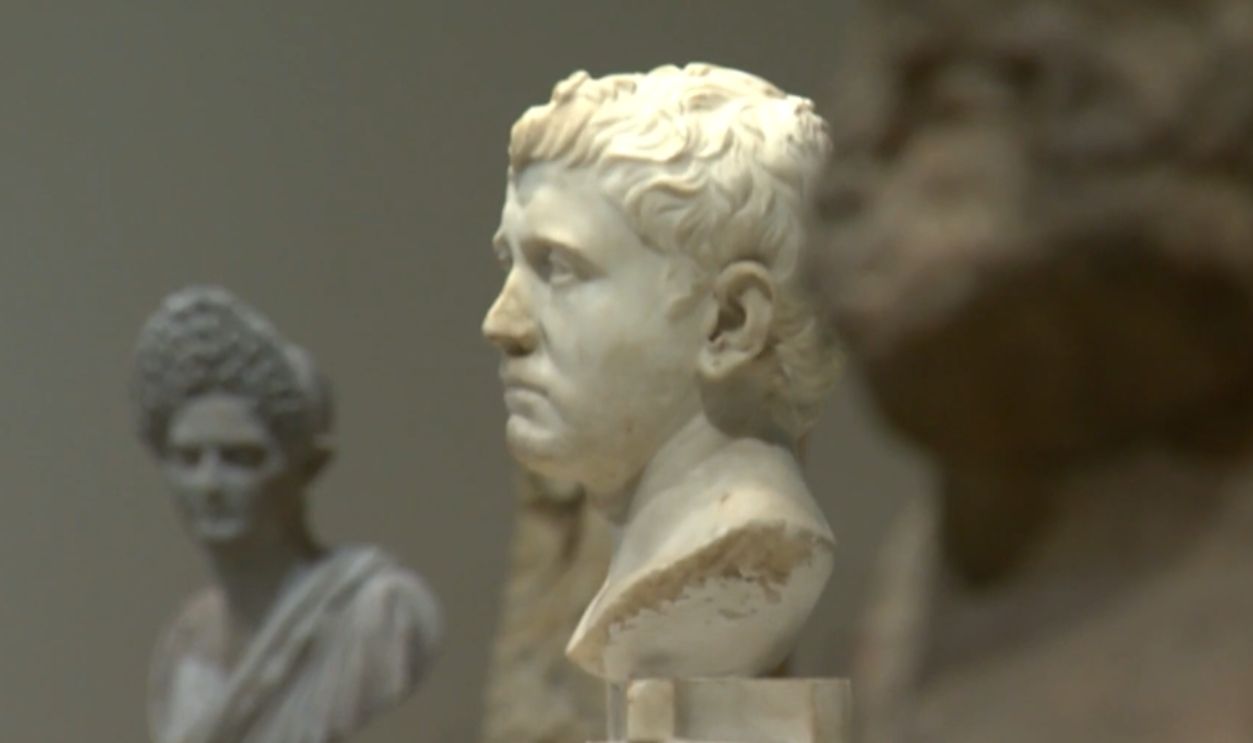

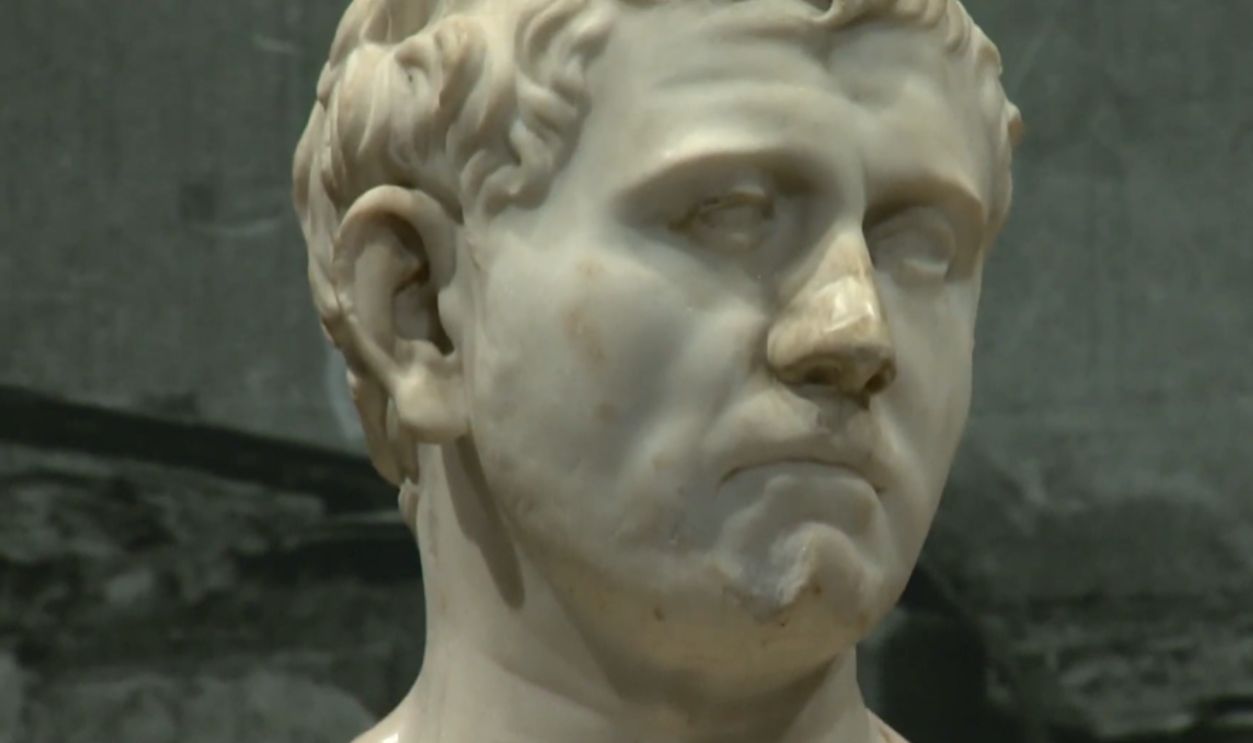

A Closer Look At The Stone

Marble reveals age in subtle ways: softened edges, micro-pitting, and an idealized yet individualized Roman portrait style. Experts would later date the head to the late 1st century BCE or early 1st century CE—exactly the era when Roman portraiture prized realism (verism) balanced with august gravitas.

Woman buys a 2000-year-old roman bust for $35 at thrift shop, WFAA

Woman buys a 2000-year-old roman bust for $35 at thrift shop, WFAA

Phone Calls, Emails, And A Hush-Hush Investigation

Young began contacting auction houses and scholars. Sotheby’s specialists advised caution: if the bust was ancient, it might also be culturally sensitive. Over months, photos, measurements, and stylistic analyses circulated privately while provenance researchers combed archives. An extraordinary conclusion emerged: this wasn’t just Roman—it was missing museum property.

From Bavaria To Texas: A Museum’s Lost Treasure

Archival photographs and records pointed to the Pompejanum in Aschaffenburg, Germany—a 19th-century idealized Roman villa created by King Ludwig I of Bavaria to house classical art. The bust had been part of that collection before vanishing in the turmoil surrounding World War II.

After Joseph Karl Stieler, Wikimedia Commons

After Joseph Karl Stieler, Wikimedia Commons

The Pompejanum’s Wartime Ordeal

The Pompejanum suffered severe damage during the war. In the conflict’s aftermath, works disappeared from the site. Decades later, Germany restored the building, but some objects—including this portrait head—remained missing, their fate unknown. Until Austin.

A Nickname And A New Life On A Credenza

While the paperwork churned, the bust acquired a household role. Young placed it on a credenza near the door, where its face reflected faintly in the TV screen at night. She even nicknamed him “Dennis,” a wry nod to his inscrutable stare and mysterious past.

Who Is He? The Identity Debate

Scholars floated candidates: perhaps Drusus Germanicus (Nero Claudius Drusus), perhaps another elite Roman. Identifying anonymous Roman portraits is notoriously tricky; hair, beard, and physiognomy were fashion as much as likeness. For now, experts agree on era and quality—but not a definitive name.

Ethics First: Returning What Was Lost

Once German authorities and the San Antonio Museum of Art (SAMA) confirmed the object’s provenance, Young agreed to a lawful path forward. Because the piece had not been legally deaccessioned or sold, it remained Bavarian state property. The priority shifted from appraisal to restitution.

Cohee at English Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

Cohee at English Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

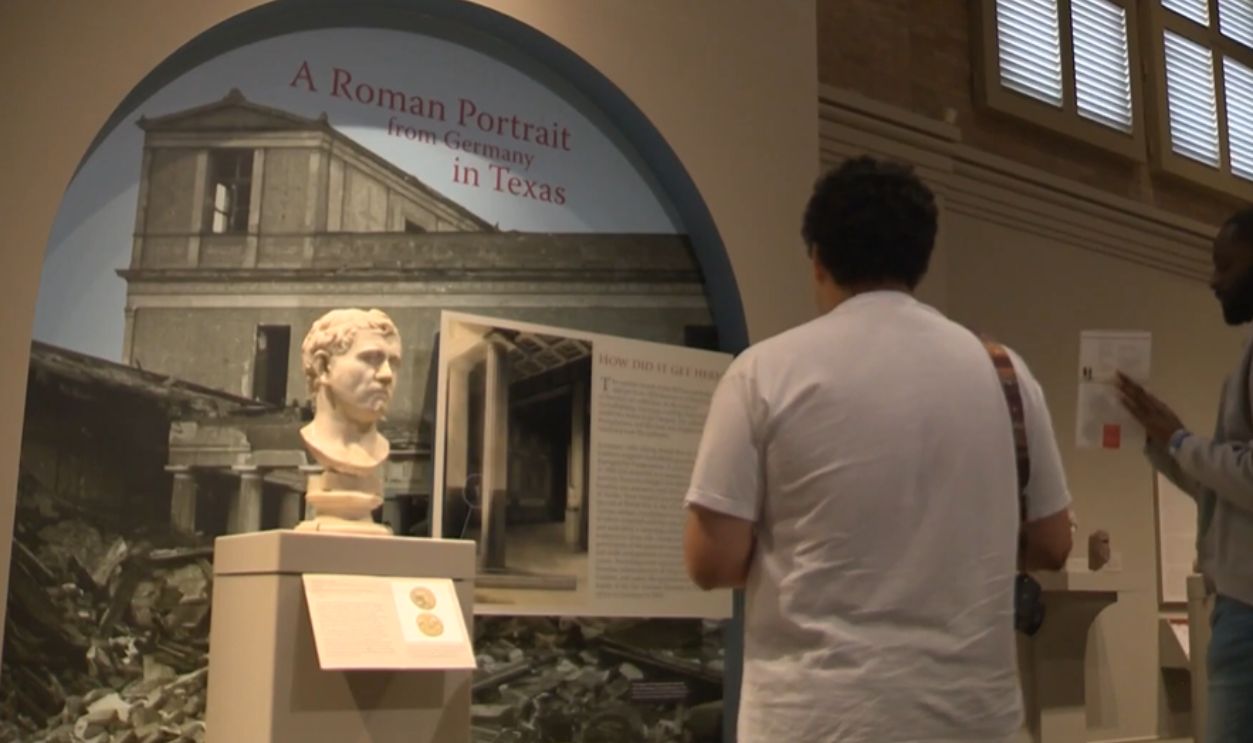

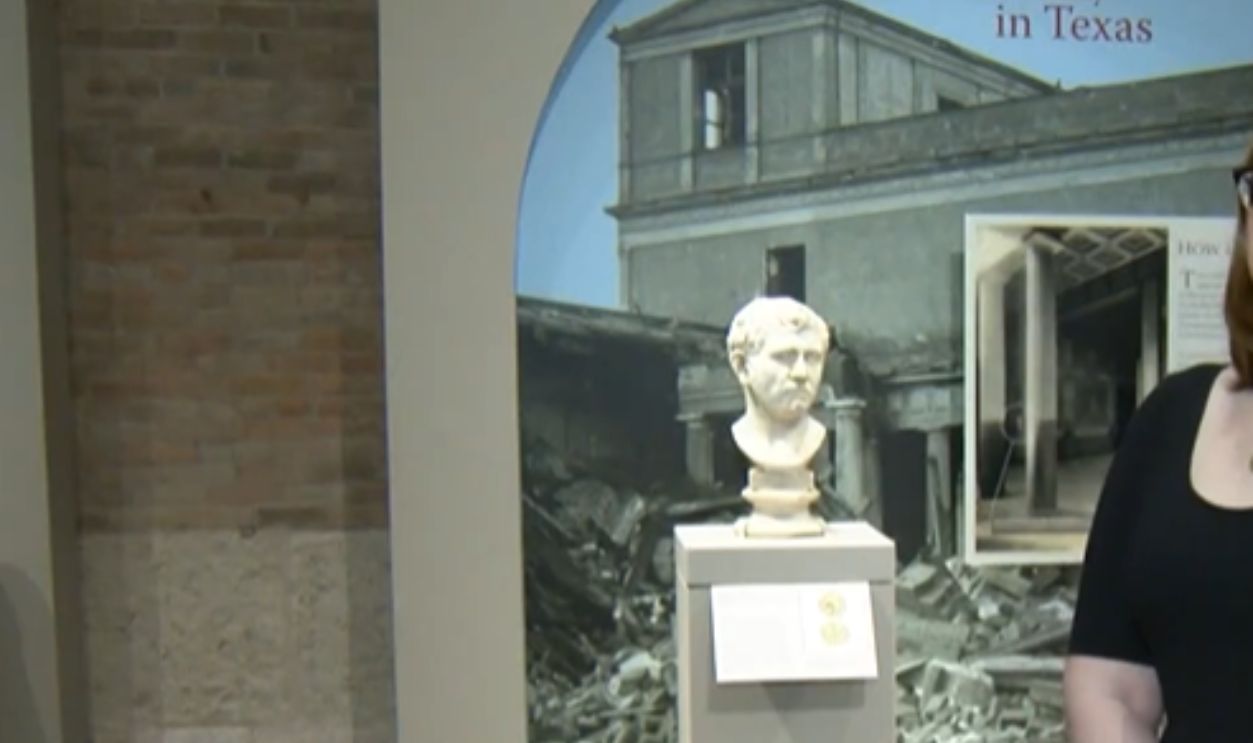

A Museum Steps In To Help

SAMA helped evaluate, display, and coordinate the sculpture’s repatriation. As SAMA announced in May 2022, the bust would be exhibited for Texans to see before traveling back to Germany, an arrangement reached with the Bavarian Administration of State-Owned Palaces, Gardens, and Lakes.

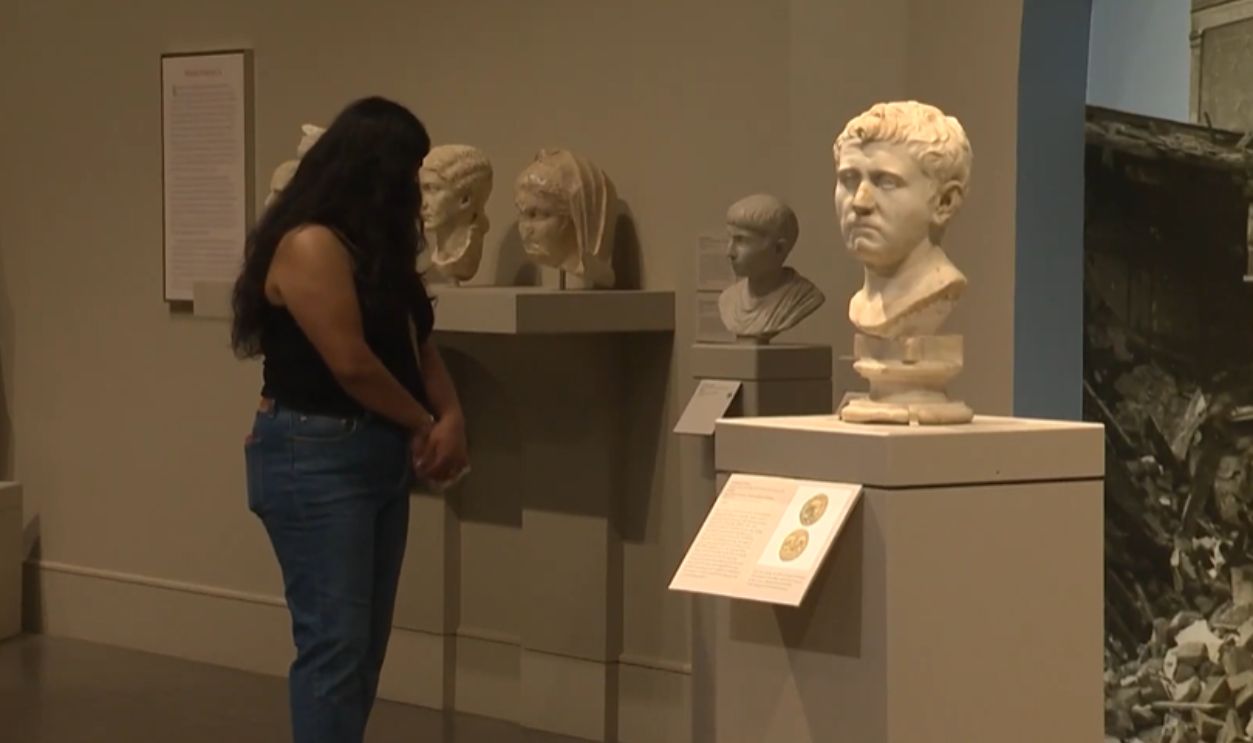

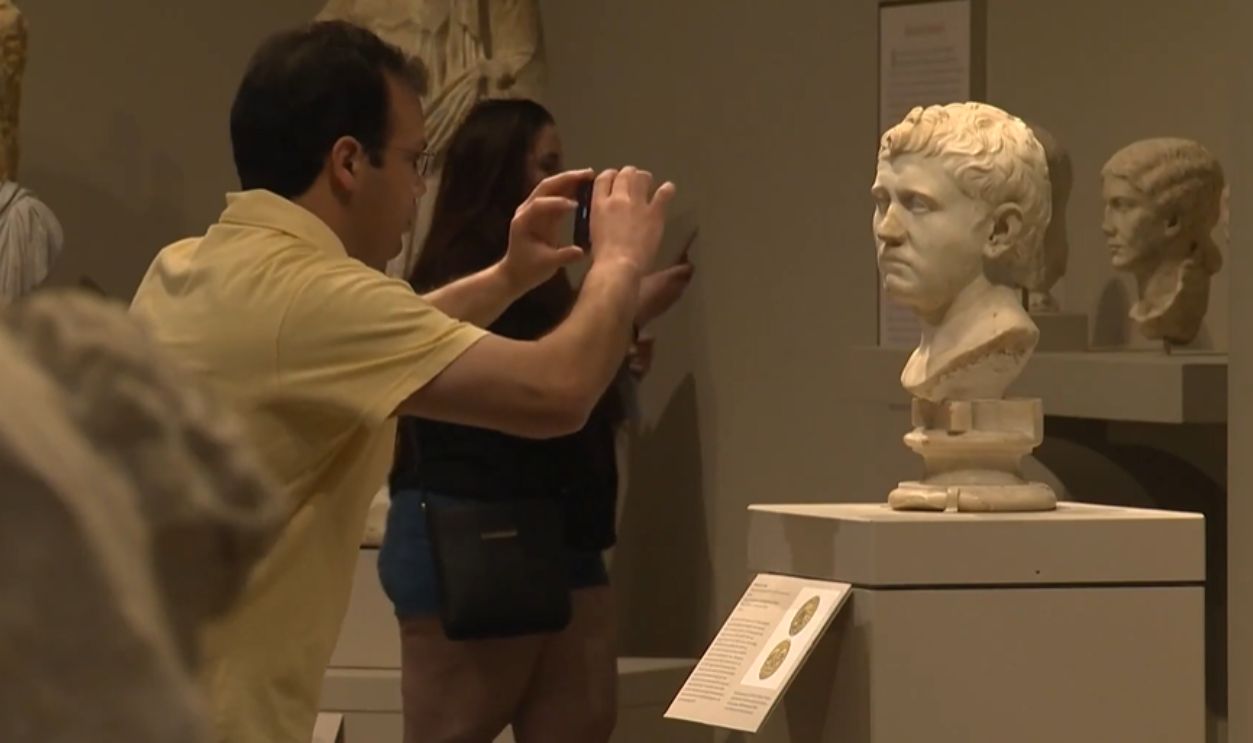

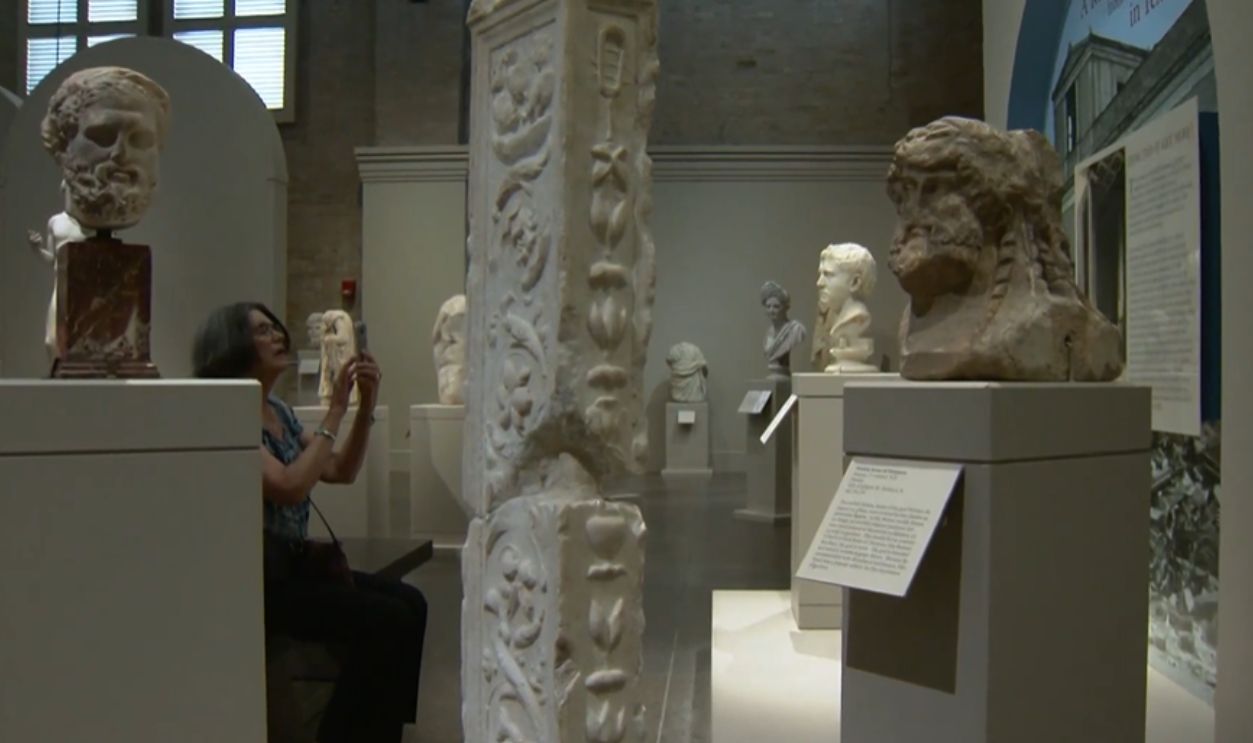

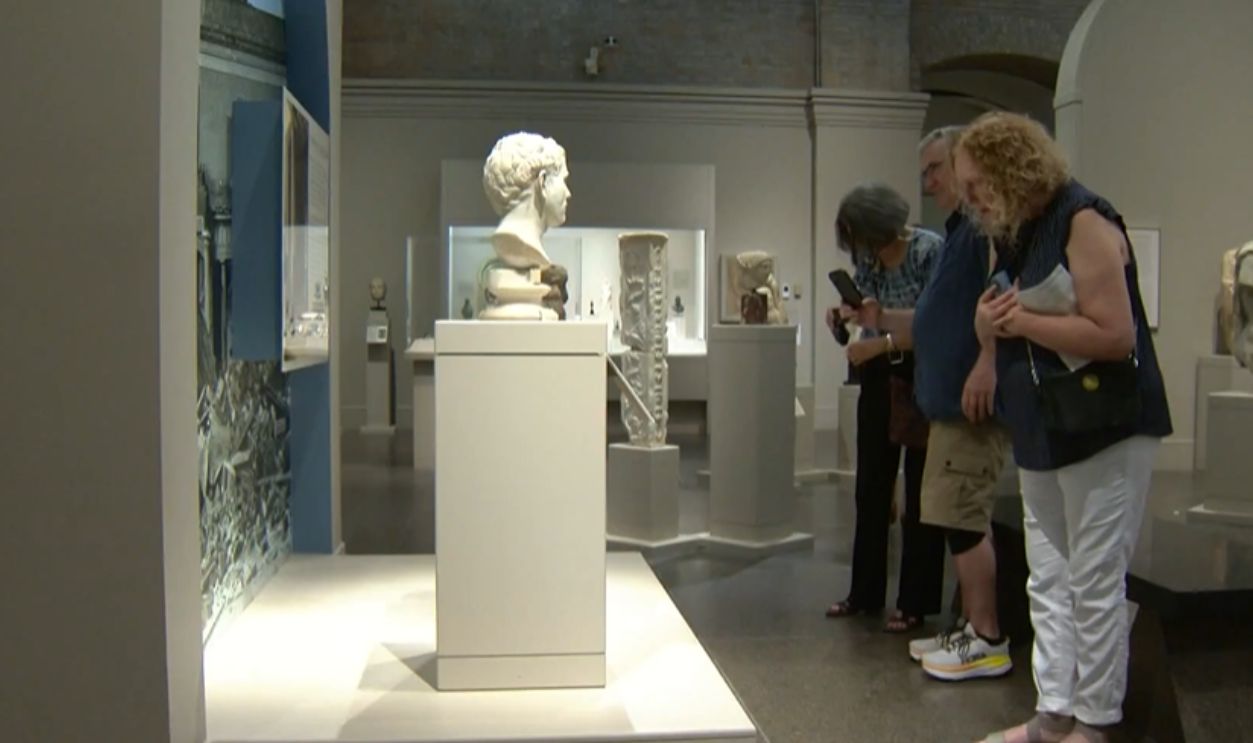

On View In San Antonio: A Farewell Tour

From 2022 into 2023, visitors to SAMA encountered the unlikely celebrity from the Austin Goodwill—a pristine lesson in Roman portraiture and cultural stewardship. The display interpreted the object’s artistic value and its tangled journey across continents and centuries.

Dating The Bust: Late Republic To Early Empire

Stylistic markers—cut of the beard, short hair, and sober expression—fit the transition between Republic and Empire. Portraits from this period often project austere virtues prized by Rome’s elite, making exact identifications challenging but the historical window clear.

Woman buys a 2000-year-old roman bust for $35 at thrift shop, WFAA

Woman buys a 2000-year-old roman bust for $35 at thrift shop, WFAA

The King Behind The Collection

King Ludwig I’s 19th-century passion for antiquity shaped Bavaria’s classical holdings, including the Pompejanum. The villa was both museum and manifesto, celebrating Roman art and domestic life with galleries of portraits, statuary, and decorative marbles. Our Goodwill bust once stood among them.

Johann Lorenz Kreul, Wikimedia Commons

Johann Lorenz Kreul, Wikimedia Commons

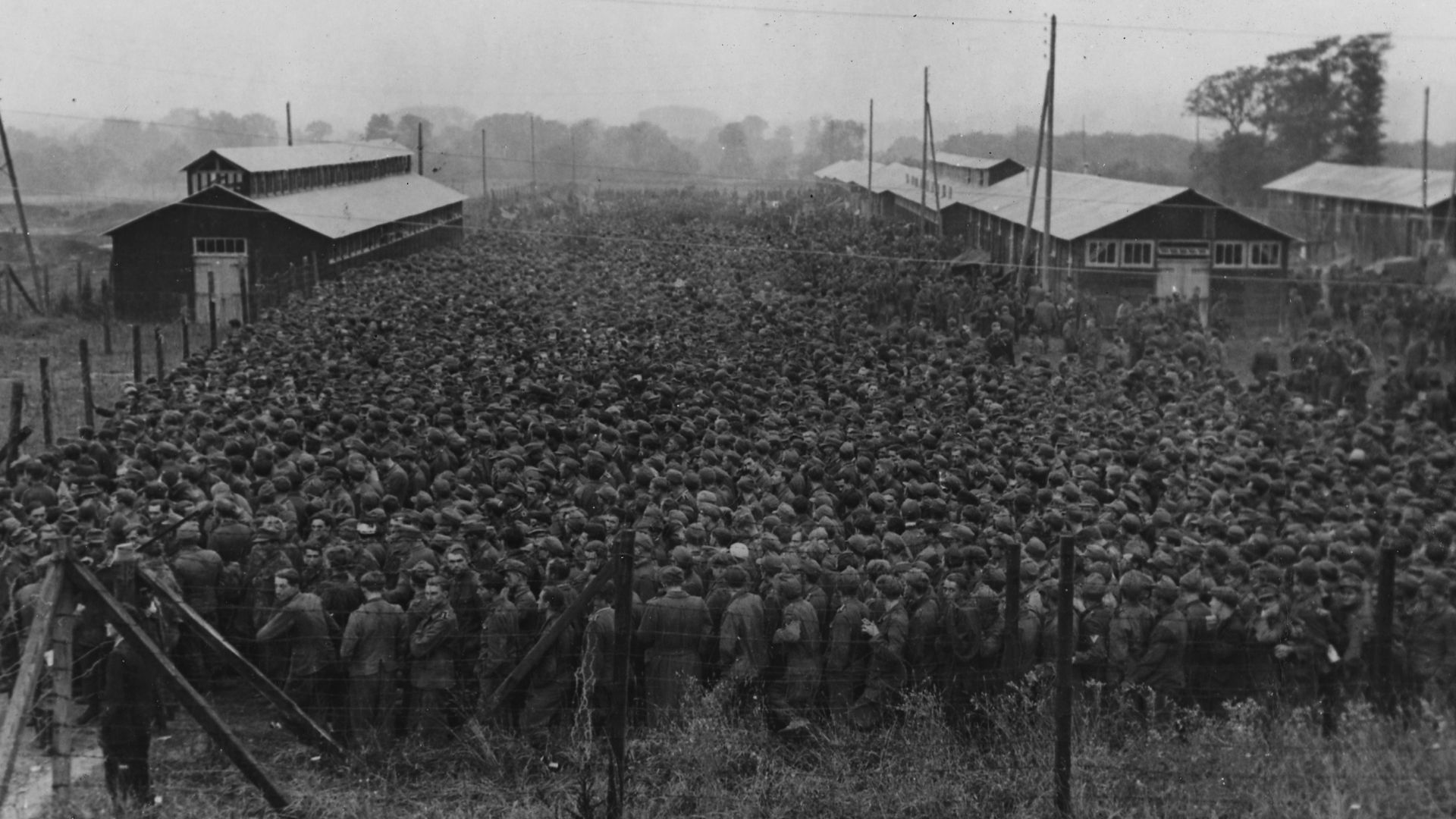

World War II And The Dispersal Of Art

The chaos of war displaced millions of artworks. Some were destroyed, others looted or simply “went missing.” The Pompejanum’s losses fit a wider pattern in which objects detached from documentation drifted into private hands, sometimes for generations.

Unknown authorUnknown author or not provided, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author or not provided, Wikimedia Commons

How Did It Cross The Atlantic?

No paper trail survives. A plausible scenario—favored by journalists and some officials—is that a U.S. service member brought the bust stateside after the war. Decades later, with heirs unaware of its significance, it may have been donated with household goods to Goodwill. It’s informed speculation, but it fits the known gaps.

Wacky Windjammer, Wikimedia Commons

Wacky Windjammer, Wikimedia Commons

Conservation Clues: Why The Bust Endured

Marble’s durability, plus the relative shelter of indoor display at the Pompejanum, helped the head survive. Its worn surfaces suggest age rather than modern fakery; its fractures and chips are consistent with historical handling and wartime disruption. Museum scholars weighed these clues alongside archival photos.

The Goodwill Moment That Changed Everything

Stories like this thrive on a single decision. Young spotted the piece beneath a table and trusted her eye. For archaeologically minded readers, it’s a reminder that context can collapse in the modern market—and that connoisseurship still matters in recognizing the ancient in the everyday.

Law, Loans, And Letters Of Agreement

The path from living-room credenza to museum vitrine runs through law. Because Bavaria maintained title, the bust couldn’t be sold. Instead, parties negotiated a temporary U.S. display followed by repatriation. It’s a textbook example of collaborative restitution rather than courtroom combat.

Why Identification Is Harder Than It Looks

Roman portrait heads were often recut; hairstyles updated; inscriptions lost. Without a base or ancient label, scholars triangulate with typologies and comparanda. That’s why opinions range from Drusus Germanicus to “unknown elite youth,” even as consensus solidifies around the date.

StarTrekker, Wikimedia Commons

StarTrekker, Wikimedia Commons

Public History Done Right

The SAMA presentation didn’t just display a trophy; it told a story of provenance research, ethics, and international cooperation—an approach museum professionals increasingly deem essential. Visitors left with art-historical context and a clear roadmap of why the bust was going home.

From Viral Sensation To Teaching Tool

Media attention turned “Dennis” into a global headline. But the coverage also amplified a practical lesson: if you stumble on something that looks authentically ancient, consult experts and check databases before selling or exporting. Cultural heritage law is intricate—and it matters.

The Homecoming To Aschaffenburg

In July 2023, Germany celebrated the bust’s return to the Pompejanum with public fanfare. After roughly 70 years, the marble head again met the light of the Main River city—a poignant reunion of object and place.

Woman buys a 2000-year-old roman bust for $35 at thrift shop, WFAA

Woman buys a 2000-year-old roman bust for $35 at thrift shop, WFAA

A Plaque For The Finder

Bavarian officials acknowledged Young’s role in the sculpture’s safe return. Reports noted she would be recognized on site—an enduring nod to a private citizen who chose stewardship over profit and helped close a long-open wartime chapter.

The $35 Goodwill Find of the Century | Laura Young | Tiny Talks Austin, Tiny Talks

The $35 Goodwill Find of the Century | Laura Young | Tiny Talks Austin, Tiny Talks

What $34.99 Really Bought

The thrift-store price didn’t purchase ownership; it bought responsibility. Young acquired custody of a displaced artifact and, with it, an ethical duty. By embracing transparency and partnering with institutions, she ensured that scholarship and the public—not secrecy—benefited.

The $35 Goodwill Find of the Century | Laura Young | Tiny Talks Austin, Tiny Talks

The $35 Goodwill Find of the Century | Laura Young | Tiny Talks Austin, Tiny Talks

Why This Story Resonates With Archaeology Fans

Archaeology is ultimately about context. Here, the context was shattered—war, dispersal, donation. Yet through research and collaboration, context was partially rebuilt: original location, collection history, and cultural significance now accompany the object anew.

Woman buys a 2000-year-old roman bust for $35 at thrift shop, WFAA

Woman buys a 2000-year-old roman bust for $35 at thrift shop, WFAA

Lessons For Collectors And Curators

Document everything; verify before you buy; and when history gets complicated, bring in professionals. Museums can serve as partners, not adversaries, in resolving provenance issues—especially when all sides commit to the public good.

The Enduring Allure Of Roman Portraiture

Beyond the headline, the bust itself captivates: the cool marble, the stern youthfulness, the compression of personality across 2,000 years. Even stripped of a name, it reflects the Roman obsession with memory and status—and our own craving to meet the past face-to-face.

Woman buys a 2000-year-old roman bust for $35 at thrift shop, WFAA

Woman buys a 2000-year-old roman bust for $35 at thrift shop, WFAA

Back On Its Plinth, Back In The Narrative

Today the head stands once again in a Roman-style villa, thousands of miles from Texas, yet indelibly tied to it by a detour through American thrift culture. Its absence is now part of its story—interpreted, not hidden—and that transparency strengthens the collection it rejoined.

Woman buys a 2000-year-old roman bust for $35 at thrift shop, WFAA

Woman buys a 2000-year-old roman bust for $35 at thrift shop, WFAA

A Modern Odyssey With An Ancient Soul

This saga began with a yellow price tag and an inquisitive eye; it ends with a homecoming and a richer public record. Between those poles stretched meticulous provenance work, ethical decision-making, and museum collaboration. For archaeology enthusiasts, the lesson is timeless: context can be lost, but with care, scholarship, and goodwill—sometimes literally—it can be found again.

Woman buys a 2000-year-old roman bust for $35 at thrift shop, WFAA

Woman buys a 2000-year-old roman bust for $35 at thrift shop, WFAA

You May Also Like:

Sorry California—These States All Have A Better Quality Of Life Than The Golden State