The Discovery That Shouldn’t Exist

In December 2025, scientists announced a finding that instantly sent shockwaves through archaeology. It hinted that our ancient ancestors were doing something astonishingly advanced… at a point in history when they weren’t supposed to know how to do it at all. And suddenly, the story of human technology may need to be rewritten from the ground up.

The Crucial Distinction: Using Fire vs. Making Fire

Early humans using natural fire? That’s old news—evidence of that stretches back nearly a million years. But making fire on demand, striking sparks, building controlled hearths? That leap has always been placed much later on the timeline. This brand-new 2025 discovery suggests ancient humans weren’t just tending flames… they were creating them long before science thought possible.

Vincent_AF from Rotterdam, Netherlands, Wikimedia Commons

Vincent_AF from Rotterdam, Netherlands, Wikimedia Commons

A Closer Look at What Was Found

Researchers didn’t stumble on a dramatic fossil. Instead, they uncovered subtle but unmistakable traces—burn patterns, fractured stone, and chemical signatures—revealed through cutting-edge analysis. The deeper they looked, the clearer it became: this wasn’t wildfire. It was deliberate, repeated, intentional fire-making from hundreds of thousands of years earlier than expected.

Grand Canyon National Park, Wikimedia Commons

Grand Canyon National Park, Wikimedia Commons

The Breakthrough Site in England

At Beeches Pit in Suffolk—the site now at the center of 2025’s biggest archaeological shake-up—scientists found heat-altered clay, intensely fractured flint, and fragments of iron pyrite, a mineral used specifically for striking sparks. These weren’t signs of borrowed flames. They were the tools of people who knew how to start fire from scratch.

Kent County Council, Jessica Bryan, 2011-04-13 16:17:15, Wikimedia Commons

Kent County Council, Jessica Bryan, 2011-04-13 16:17:15, Wikimedia Commons

Why This Discovery Changes Everything

Fire-making is a cognitive milestone: it requires planning, material knowledge, repeated practice, and cultural teaching. The 2025 findings show ancient humans wielded this knowledge far earlier than expected, suggesting they were more sophisticated than past timelines ever allowed.

None, Adam Daubney, 2008-07-07 10:22:28, Wikimedia Commons

None, Adam Daubney, 2008-07-07 10:22:28, Wikimedia Commons

The Stone That Proves It: Iron Pyrite

Iron pyrite doesn’t ignite naturally—it must be deliberately struck against flint to create sparks. The pyrite fragments at Beeches Pit showed distinctive wear patterns, which archaeologist Dr. Filipe Natalio described as “the first unambiguous proof of fire production by ancient humans,” underscoring just how intentional this behavior was.

James Petts from London, England, Wikimedia Commons

James Petts from London, England, Wikimedia Commons

AI Helped Uncover Invisible Evidence

Using machine-learning techniques, researchers detected microscopic thermal signatures on tools—patterns too subtle for the human eye. This technology allows scientists to identify ancient fires even when visible ash has long disappeared, turning old artifacts into brand-new evidence.

Dr John Wells, Wikimedia Commons

Dr John Wells, Wikimedia Commons

These Weren’t Accidental Fires

Thermal testing revealed temperatures above 700°C, far hotter than natural brush fires. The repeated heating of the same spot shows this was a purpose-built hearth used over and over, not a one-time event.

Kent County Council, Walter (Jo) Ahmet, 2017-02-13 16:28:33, Wikimedia Commons

Kent County Council, Walter (Jo) Ahmet, 2017-02-13 16:28:33, Wikimedia Commons

Early Neanderthals Were the Fire-Makers

Around 400,000 years ago, Britain was home to early Neanderthals. This discovery reveals they weren’t just opportunistic fire-users—they were capable, knowledgeable fire-makers. As one researcher put it, “They weren’t simply gathering fire. They knew how to make it.”

Jakub Hałun, Wikimedia Commons

Jakub Hałun, Wikimedia Commons

Fire-Making vs. Fire-Using

Humans may have used naturally occurring fire far earlier—but creating fire on demand is the true technological leap. The 2025 findings push that leap dramatically earlier, reshaping our understanding of early human innovation.

Bristol City Council, Kurt Adams, 2005-12-02 17:02:34, Wikimedia Commons

Bristol City Council, Kurt Adams, 2005-12-02 17:02:34, Wikimedia Commons

Evidence From Israel Adds Support

At Gesher Benot Ya’aqov, archaeologists found burned seeds, charred wood, and tools dating back 780,000 years—suggesting repeated, controlled fire use but not definitive fire-making.

Benno Rothenberg, Wikimedia Commons

Benno Rothenberg, Wikimedia Commons

South Africa’s One-Million-Year Clue

Inside Wonderwerk Cave, burned bones and ash date to nearly 1 million years ago. Paleoanthropologist Dr. Francesco Berna noted that the burning occurred “deep inside the cave, which is strongly indicative of controlled fire,” suggesting early humans were managing flames—but still not making them like those at Beeches Pit.

user:omarshehab, Wikimedia Commons

user:omarshehab, Wikimedia Commons

The Missing Link Has Finally Emerged

For years, scientists had evidence of controlled fire scattered across continents but lacked solid proof of how early humans obtained it. The Beeches Pit pyrite fragments close that gap, offering the first direct evidence of ancient spark-making tools.

Phyzome is Tim McCormack, Wikimedia Commons

Phyzome is Tim McCormack, Wikimedia Commons

Why This Changes Human Behavior Models

Deliberate fire-making implies advanced behaviors: planning, teaching, cooperation, experimentation, and tool specialization. This wasn’t improvisation—it was early technology.

Sussex Archaeological Society, Stephanie Smith, 2016-04-03 19:17:45, Wikimedia Commons

Sussex Archaeological Society, Stephanie Smith, 2016-04-03 19:17:45, Wikimedia Commons

Fire May Have Transformed Diet Much Earlier

Cooking softens food, boosts caloric extraction, and supports larger brains—an idea captured by anthropologist Dr. Richard Wrangham, who famously said that “cooking made us human.” If fire-making dates back this far, it implies cooking may have shaped ancient human life far earlier than previously assumed.

Bengt Oberger, Wikimedia Commons

Bengt Oberger, Wikimedia Commons

Safer Nights and Organized Living

Fire didn’t just warm early humans—it reshaped how they lived. A controlled flame kept predators at bay, made cold nights survivable, and created a central gathering point. The Beeches Pit hearth may be one of the earliest intentionally organized living spaces, showing ancient humans were already shaping their environment with purpose.

Godfrey Emmanuel, Wikimedia Commons

Godfrey Emmanuel, Wikimedia Commons

Firelight Reshaped Social Life

Once groups gathered around a steady fire, evenings became opportunities for connection. Firelight extended waking hours, encouraged teaching and storytelling, and helped bond communities. Researchers believe these nightly gatherings played a major role in early cultural development, turning the hearth into one of humanity’s first shared social spaces.

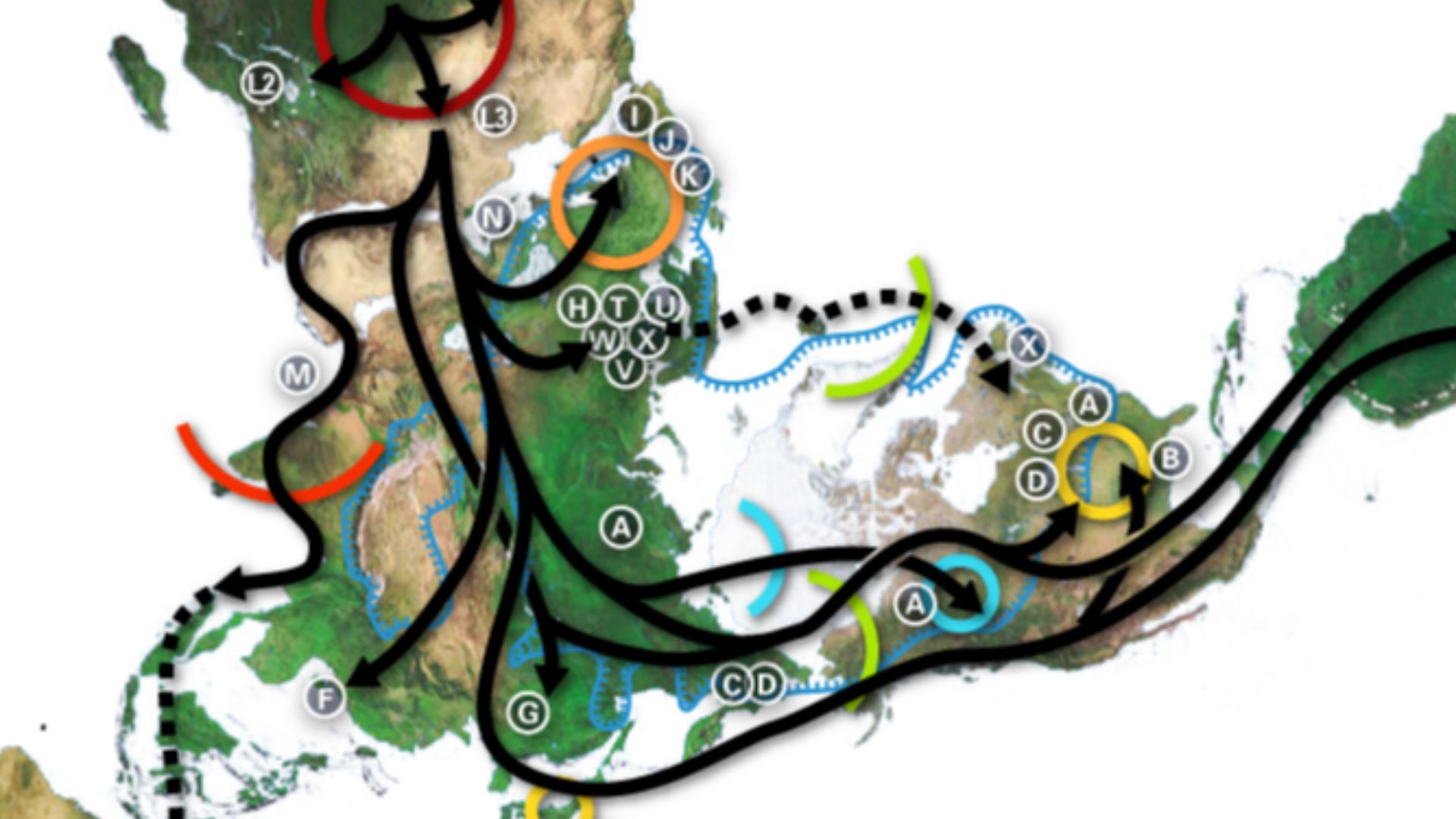

Migration Made Possible

Reliable fire-making let early humans push into colder regions once thought too harsh to inhabit. Warmth, cooked food, and protection allowed them to endure unfamiliar landscapes. This capability likely supported early movements across Ice Age Europe.

WI resident, Wikimedia Commons

WI resident, Wikimedia Commons

Heat-Treated Tools Suggest Deeper Knowledge

Some flint pieces show fractures caused by controlled heating, suggesting early humans were intentionally manipulating materials to create sharper, more effective tools—another sign of technological sophistication.

Copyright retained by illustrator, Graham Hill, 2012-08-30 13:39:34, Wikimedia Commons

Copyright retained by illustrator, Graham Hill, 2012-08-30 13:39:34, Wikimedia Commons

Machine Learning Is Rewriting Archaeology

AI can detect tiny thermal changes on stone artifacts, transforming seemingly ordinary objects into historical breakthroughs. Researchers expect many museum collections to reveal new evidence when reexamined with these tools.

Baoquan Song, Wikimedia Commons

Baoquan Song, Wikimedia Commons

Other Sites May Soon Fall Into Line

Scientists now suspect multiple sites in Europe, Africa, and the Middle East may hold similar thermal signatures. Beeches Pit is likely the first of many major reinterpretations.

Experts Call It a Landmark Discovery

Researchers described the find as a “milestone” that challenges long-held assumptions about human innovation. Scientific American noted the results may require a full rewrite of early technology timelines.

Cotswold Archaeology, Wikimedia Commons

Cotswold Archaeology, Wikimedia Commons

What Remains Unknown

Questions remain: Which hominin groups mastered fire-making first? How widely was the technique shared? How quickly did it spread across regions? The 2025 findings open the door to answers long out of reach.

A New Story of Fire

Fire wasn’t a late invention—it was a skill ancient humans mastered astonishingly early. And thanks to new technology, we’re finally seeing our ancestors not as passive survivors, but as innovators who learned to engineer their world long before history began recording them.

You Might Also Like: