A Discovery That Sat Quietly for Decades

Some of the most important archaeological discoveries don’t make headlines right away. This story begins with bones uncovered nearly a century ago, quietly stored, studied, and debated. Only recently did new technology allow scientists to revisit them—and realize they may be telling a much bigger story about our ancient past.

The Child at the Center of the Mystery

The remains belong to a young child, estimated to have died around age five. The bones were discovered in Skhul Cave in present-day Israel, a site already known for early human fossils. At first glance, nothing about the skeleton seemed revolutionary. That changed with closer inspection.

Why Scientists Took Another Look

For decades, the fossil resisted easy classification. Some traits looked distinctly human. Others didn’t. Advances in imaging technology finally gave researchers a reason to return to the remains, hoping modern tools could answer questions older methods couldn’t.

Technology Changed Everything

Using high-resolution CT scans and 3D modeling, researchers were able to examine the skull, jaw, and inner ear without damaging the fossil. These tools revealed details invisible to earlier scientists—and those details didn’t point to just one human lineage.

A Mix That Shouldn’t Exist—But Does

Parts of the skull resemble early Homo sapiens. Other features, especially in the inner ear and jaw, align more closely with Neanderthals. According to researchers, this unusual combination forms a mosaic pattern—something rarely seen unless populations have mixed.

Neanderthal-Museum, Mettmann, Wikimedia Commons

Neanderthal-Museum, Mettmann, Wikimedia Commons

Why the Age of the Fossil Matters

The child lived roughly 140,000 years ago. That’s the shock. Until now, most physical evidence of human–Neanderthal interbreeding dated to tens of thousands of years later. This pushes that interaction much further back in time than scientists expected.

What “Inbreeding” Means Here

In this context, inbreeding doesn’t imply isolation or dysfunction. It simply refers to repeated interbreeding between closely related human populations over generations. Scientists say this kind of genetic mixing would have been common as groups overlapped and migrated.

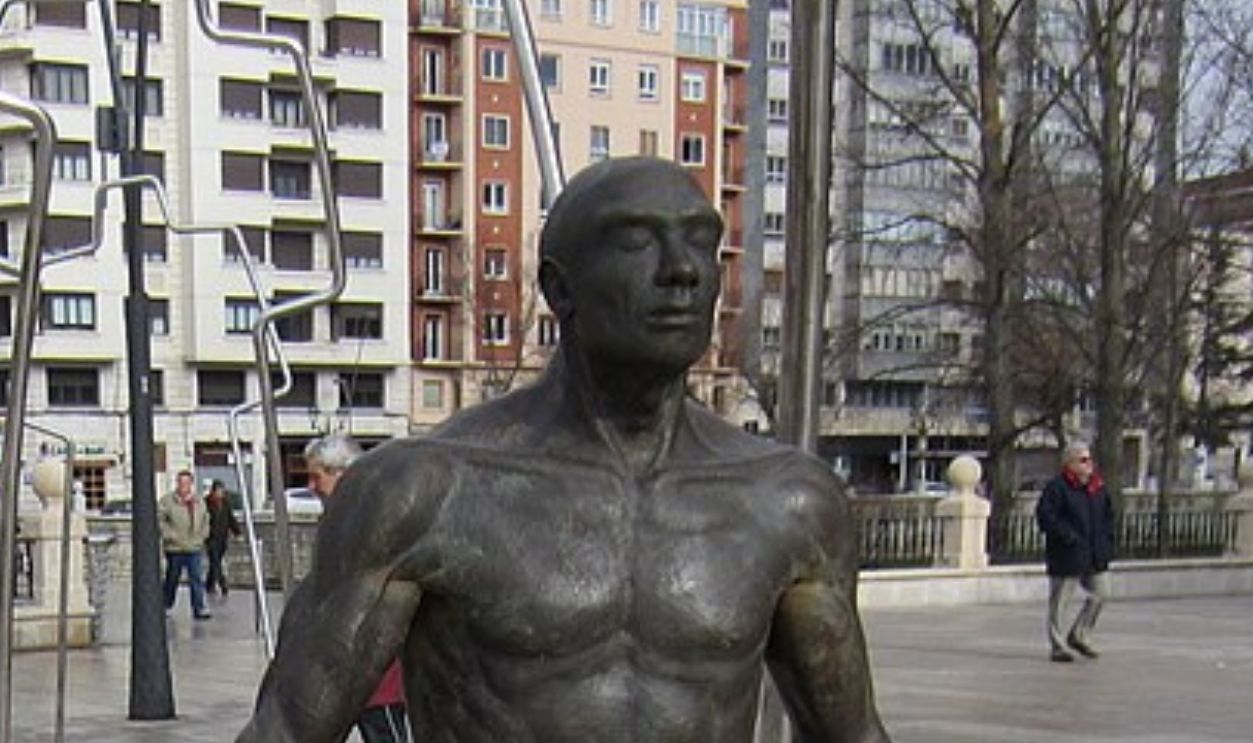

Ausejo1000, CC BY-SA 3.0 ES, Wikimedia Commons

Ausejo1000, CC BY-SA 3.0 ES, Wikimedia Commons

Scientists Are Careful—but Clear

We are looking at a population that cannot be neatly categorized, said one researcher involved in the study. The team stresses they’re not claiming a single event—but evidence of long-term interaction between humans and Neanderthals in the region.

Why Skhul Cave Keeps Reappearing

Skhul Cave has long puzzled archaeologists. Fossils from the site show a blend of traits even in adults. This child strengthens the idea that the area was a crossroads where different human groups met, lived nearby, and possibly formed families.

No DNA—But Strong Clues

Ancient DNA has not yet been recovered from the bones, which limits absolute proof. Still, experts say skeletal anatomy can be just as revealing. As one anthropologist put it, Bones preserve behavior when DNA does not.

This Isn’t the First Hybrid Hint

The famous Lapedo child from Portugal—dating to about 28,000 years ago—also showed mixed features. That discovery was controversial at first but later accepted. Scientists now see the Skhul child as evidence that such mixing happened much earlier.

National Cancer Institute, Unsplash

National Cancer Institute, Unsplash

Rethinking Human Separation

For years, humans and Neanderthals were portrayed as separate species that barely interacted. Discoveries like this suggest something far more complex—shared landscapes, shared tools, and shared bloodlines spanning thousands of years.

Neanderthal-Museum, Mettmann, Wikimedia Commons

Neanderthal-Museum, Mettmann, Wikimedia Commons

Neanderthal DNA Is Still With Us

Modern genetic studies show that most people outside Africa carry between 2 and 6 percent Neanderthal DNA. That genetic legacy supports the idea that interbreeding wasn’t rare—and that some ancient mixing had lasting effects.

Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Wikimedia Commons

Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Wikimedia Commons

Why a Child Fossil Is Especially Important

Children’s bones preserve growth patterns that adults don’t. Those patterns can reveal inherited traits more clearly. Researchers say that makes this fossil especially valuable for identifying blended ancestry in ancient populations.

OpenStax Anatomy and Physiology, Wikimedia Commons

OpenStax Anatomy and Physiology, Wikimedia Commons

Not a One-Off Encounter

The researchers emphasize this wasn’t likely a single accidental pairing. The anatomy suggests repeated contact over time—possibly generations—between neighboring human groups who didn’t see themselves as fundamentally different.

Neanderthal-Museum, Mettmann, Wikimedia Commons

Neanderthal-Museum, Mettmann, Wikimedia Commons

What This Means for Human Evolution

Rather than a clean evolutionary tree, scientists now describe human history as a braided stream—branches separating, reconnecting, and influencing one another. This fossil fits neatly into that emerging picture.

Human_evolution_scheme.svg: M. Garde derivative work: Gerbil (talk), Wikimedia Commons

Human_evolution_scheme.svg: M. Garde derivative work: Gerbil (talk), Wikimedia Commons

Why This Discovery Took So Long

The bones were always there. What changed was perspective. New tools, new questions, and a willingness to challenge old assumptions allowed scientists to see what earlier generations couldn’t—or weren’t ready to accept.

John Day Fossil Beds National Monument staff (National Park Service), Wikimedia Commons

John Day Fossil Beds National Monument staff (National Park Service), Wikimedia Commons

Caution Without Dismissal

Researchers stop short of absolute claims, but they’re confident about the implications. As one scientist noted, This find forces us to reconsider how early and how often human groups interacted.

A Story Still Unfolding

Future discoveries—or even recovered DNA—could confirm these conclusions or refine them further. For now, the Skhul child stands as one of the strongest signs yet that humans and Neanderthals were connected far earlier than believed.

A Shared Past Written in Bone

This child lived and died long before recorded history, but their remains continue to inform how we understand our origins. The distinction between “us” and “them” may not be as clear-cut as once assumed.

You Might Also Like: