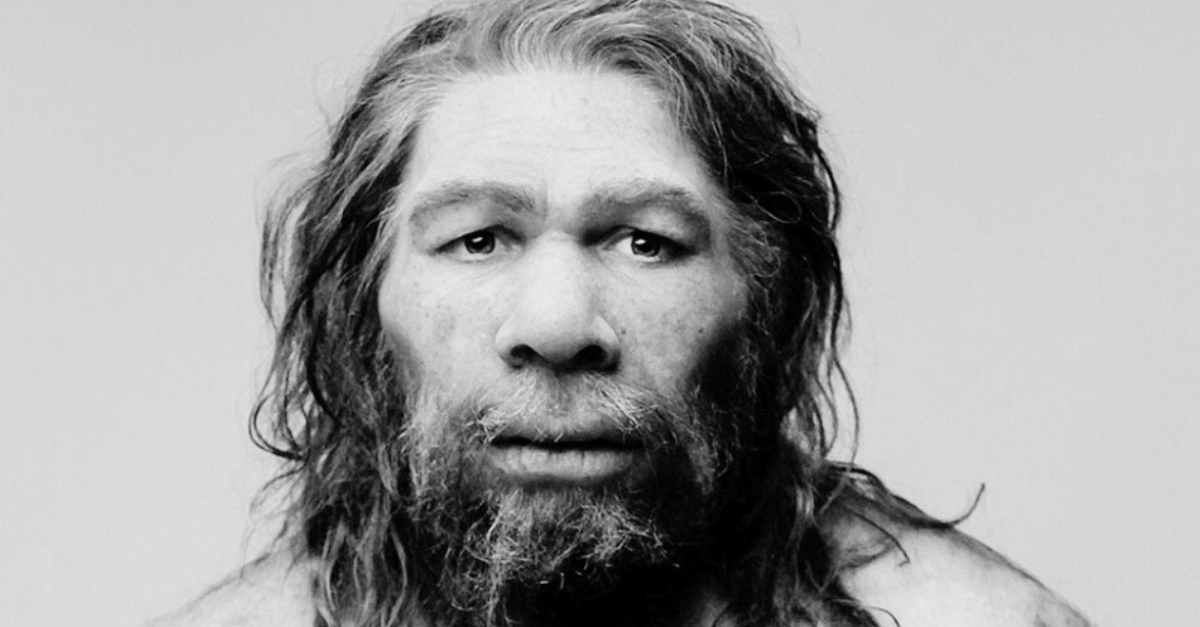

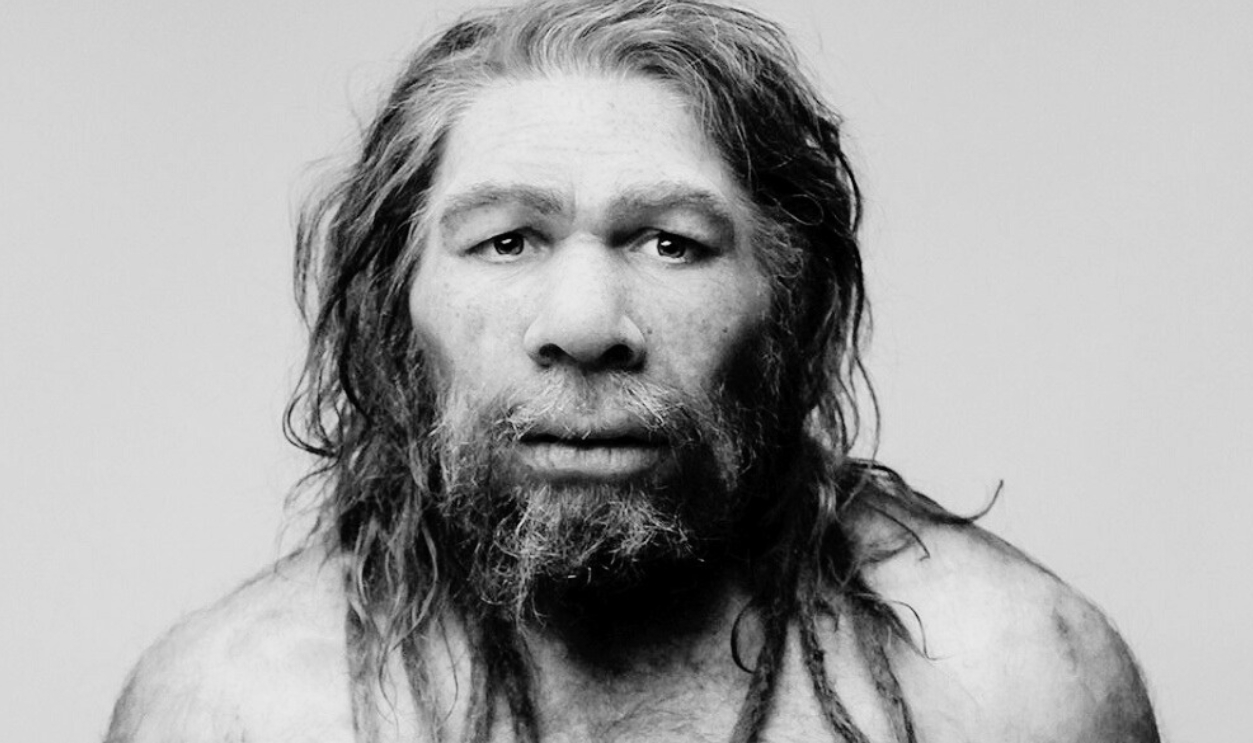

Who Were The Neanderthals

Neanderthals lived across Europe and western Asia from about 400,000 to 40,000 years ago. Their bodies handled cold weather, and their shelters relied on steady fires. Evidence from caves shows they used simple tools and cooked meals depending on the food available on nearby land.

Why Researchers Recreated Their Cooking

A recent project published through Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology tried to copy how Neanderthals cooked. The research team built open fires and handled wild game with stone flakes. Their goal was to see how heat shaped bone texture, food safety, and chemical traces.

Neanderthal-Museum, Mettmann, Wikimedia Commons

Neanderthal-Museum, Mettmann, Wikimedia Commons

What Sparked The Experiment

Hardy’s PNAS work revealed cooked plant starches and smoke particles locked in Neanderthal dental calculus. Those tiny fragments raised questions about how their meals looked in real life. It encouraged researchers to recreate fires and foods under controlled conditions to study hidden risks.

Neanderthal-Museum, Mettmann, Wikimedia Commons

Neanderthal-Museum, Mettmann, Wikimedia Commons

How The Fire Was Recreated

The team shaped shallow hearths based on cave findings. Scavenged wood types matched those identified in ancient layers. A basic flame was all they used. No modern tools entered the setup, allowing the heat and smoke to behave in a way Neanderthals would recognize.

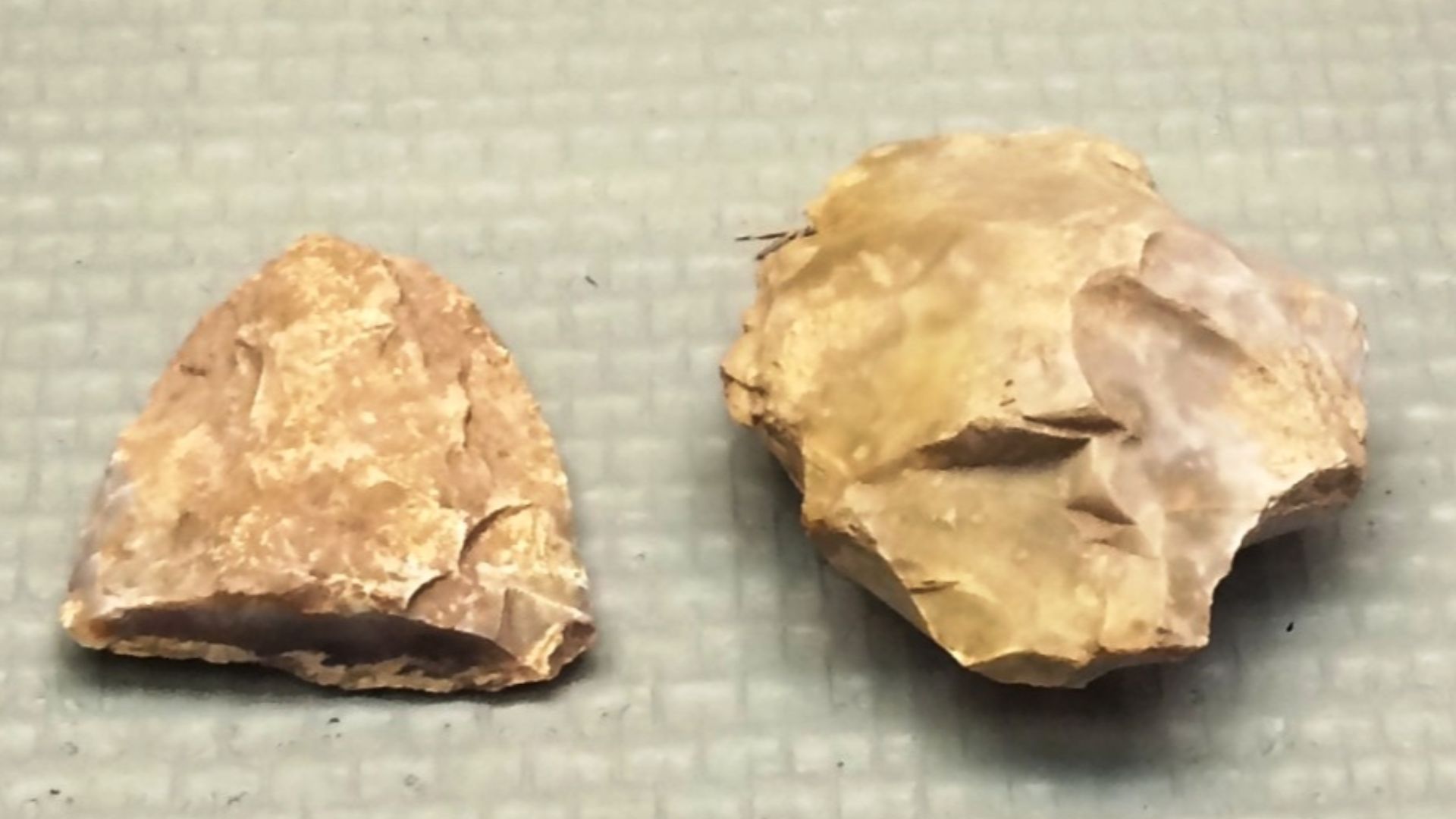

The Tools Used In The Trial

Stone flakes replaced knives. Each flake was shaped to match edges found in Neanderthal sites. The team used these sharp pieces to cut tough meat and roots. Their goal was to see how those edges changed the food and left marks on the bone.

Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, Wikimedia Commons

Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, Wikimedia Commons

Why The Ingredients Mattered

The food list came directly from confirmed evidence. Roots, seeds, and meat types found in Neanderthal teeth guided every choice. Using exact ingredients allowed the team to test whether certain plants held toxins and whether specific cuts of meat carried extra safety challenges.

Cathal Mac an Bheatha, Unsplash

Cathal Mac an Bheatha, Unsplash

What The Fire Did To The Food

Heat spread unevenly across the simple hearth. Some pieces softened quickly while others barely reacted. The cooking trials showed that Neanderthals probably dealt with unpredictable flames. That uneven heat made it easy for food to stay undercooked or grow unsafe in certain spots.

A First Clear Warning Sign

Certain wild roots turned risky if they didn’t stay near strong flames long enough. Tough fibers trapped natural toxins that needed steady heat to break down. The experiment showed that even a small drop in temperature created a meal that strained the body.

Hidden Dangers Inside Wild Meat

Wild animals carried parasites and microbes that survived in cool sections of thick cuts. The cooking trials showed how uneven heat let those threats remain active. Archaeologists link this problem to signs of digestive stress in some Neanderthal remains, which point to real health consequences from their meals.

Smoke And Firewood Created A Serious Hazard

Certain woods used in ancient hearths released heavy resins that filled enclosed caves with dense smoke. The cooking trials showed how quickly soot settled on food. Hardy’s dental evidence supports this, revealing long-term exposure to those particles inside Neanderthal mouths and lungs.

Signs Of Long-Term Strain In Their Bodies

Skeletal studies show Neanderthals carried marks linked to repeated stress and infection. Some ribs and limb bones display patterns that fit chronic inflammation. These clues suggest their daily meals, fire smoke, and frequent exposure to raw animal material placed steady pressure on the body.

Evidence Of Nutritional Stress In Certain Groups

Several Neanderthal remains contain growth interruptions in teeth and bones. Those interruptions appear during periods of poor nutrition. Researchers view these markers as signs that food shortages struck some groups, especially in colder seasons when safe plants and large animals were harder to find.

Foraging Demands Shaped Their Survival

Gathering edible plants required constant searching through rough terrain. Some regions produced only a few safe roots at certain times of year. The limited range of dependable foods forced Neanderthals to spend long hours outdoors, which increased the risk of injury and exposure.

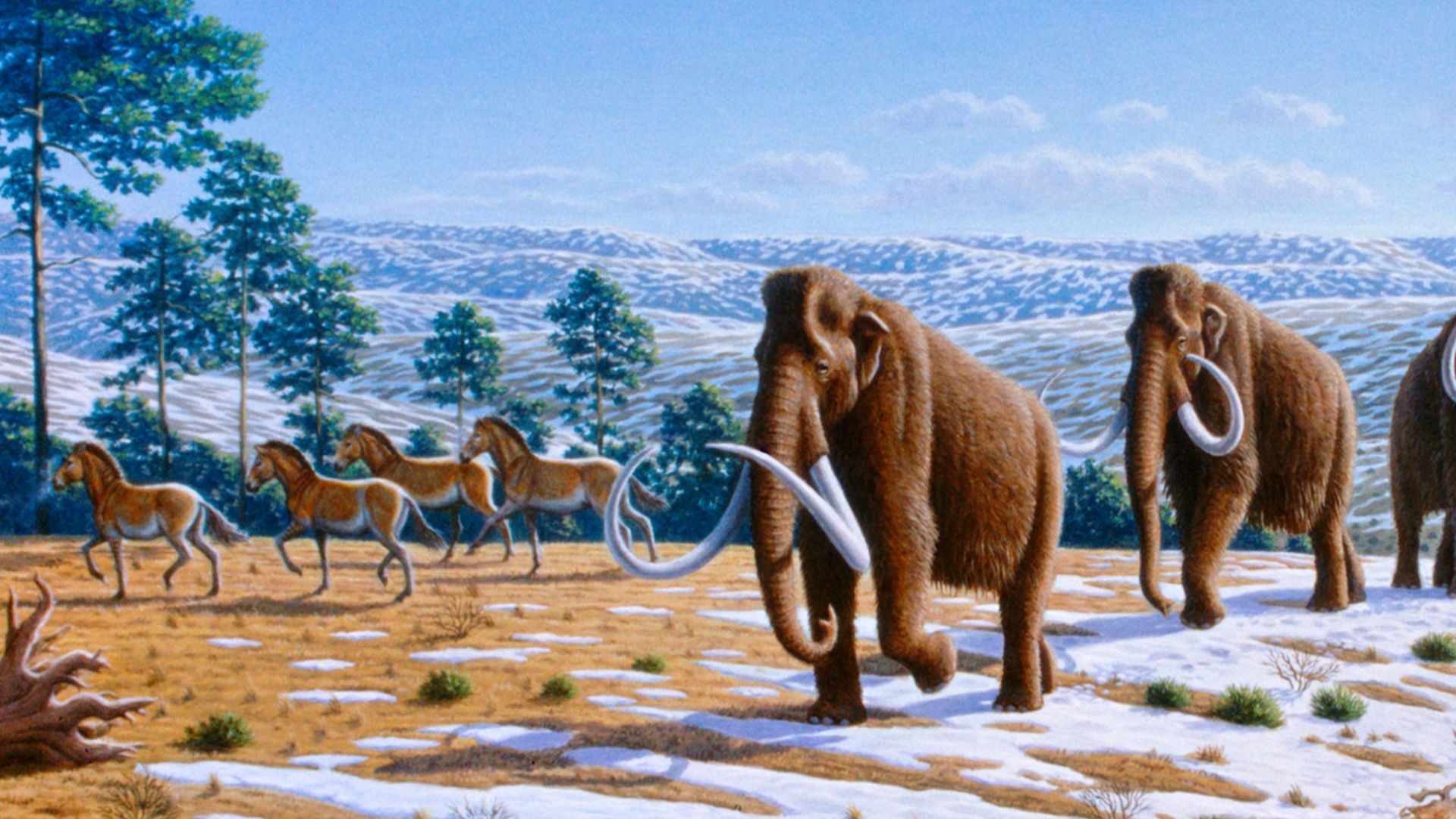

Bone Evidence Shows Shifts In Food Availability

Cuts on animal bones from different layers of cave floors show changing hunting patterns. Some layers have large herbivores, while others include smaller game. These shifts reveal how Neanderthals adjusted their meals as local herds moved, declined, or became too hard to reach.

Ian Cunliffe, Wikimedia Commons

Ian Cunliffe, Wikimedia Commons

Ecosystems Felt The Pressure Of Their Hunting

Large Ice Age animals did not rebound quickly after heavy hunting. Research on regional deposits shows slow herd recovery. Neanderthal groups relying on the same hunting grounds year after year likely faced shrinking resources, pushing them into harsher lands with fewer reliable food sources.

Mauricio Antón, Wikimedia Commons

Mauricio Antón, Wikimedia Commons

Energy Costs Didn’t Always Match The Reward

A single large animal delivered a huge meal, but reaching it demanded immense effort. Tracking, cutting, and hauling came with steep energy costs. Experiments with stone tools highlight how much work was lost to slow butchering, leaving Neanderthals with less usable food than expected from each hunt.

Cooking Methods Shaped Their Survival Odds

The open-hearth style tested in the Frontiers experiment produced useful heat but offered little control. Food safety depended on luck as much as skill. That reality meant every meal carried risks, and those risks likely influenced how long groups could remain in certain environments.

Neanderthal-Museum, Mettmann, Wikimedia Commons

Neanderthal-Museum, Mettmann, Wikimedia Commons

Food Shortages Forced Constant Movement

Some Neanderthal sites show short-term occupations with few food remains, suggesting groups left quickly once resources thinned out. This pattern hints at a cycle of moving, hunting, and moving again, driven by shrinking supplies rather than preference. Their mobility often reflected pressure, not choice.

Trougnouf (Benoit Brummer), Wikimedia Commons

Trougnouf (Benoit Brummer), Wikimedia Commons

Water Sources Added Their Own Hazards

The sediment near certain cave entrances reveals water that carried soil microbes and animal waste. Neanderthals relied on these streams without purification. Drinking from these spots increased exposure to bacteria that modern systems can easily remove.

Seasonal Climate Swings Controlled Their Options

Colder months reduced the availability of edible plants and pushed animals into harder terrain. Neanderthal sites reveal thinner food layers during these periods. Groups depended heavily on whatever they could catch, creating sharp contrasts between seasons of abundance and seasons marked by real scarcity.

Stone Tools Wore Down Faster Than Expected

Microscopic studies of tool edges reveal heavy wear from processing meat, scraping hides, and shaping wood. Each task dulled the stone quickly. Frequent reshaping reduced tool size over time, which forced Neanderthals to make new flakes again and again, often during periods of food pressure.

Shelters Offered Little Protection From Elements

Rock shelters and shallow caves shielded Neanderthals from wind, but temperatures inside dropped sharply at night. Sediment layers show repeated attempts to rebuild hearths in the same areas, suggesting constant effort to keep living spaces warm. Limited insulation made long stays physically demanding.

Their World Left Little Room For Error

Neanderthals lived in environments where a single mistake carried real consequences. A weak fire, a spoiled cut of meat, or smoke trapped in a cave could shape their health for weeks. These conditions framed survival as a delicate balance rather than a steady routine.

Experiments Offer A Window Into Their Reality

Modern cooking tests reveal details that archaeology alone can’t show. A small shift in heat changes how bones react, and smoke settles in ways that linger inside a closed shelter. Each outcome helps researchers understand how difficult ordinary tasks became for Neanderthals trying to prepare a simple meal.

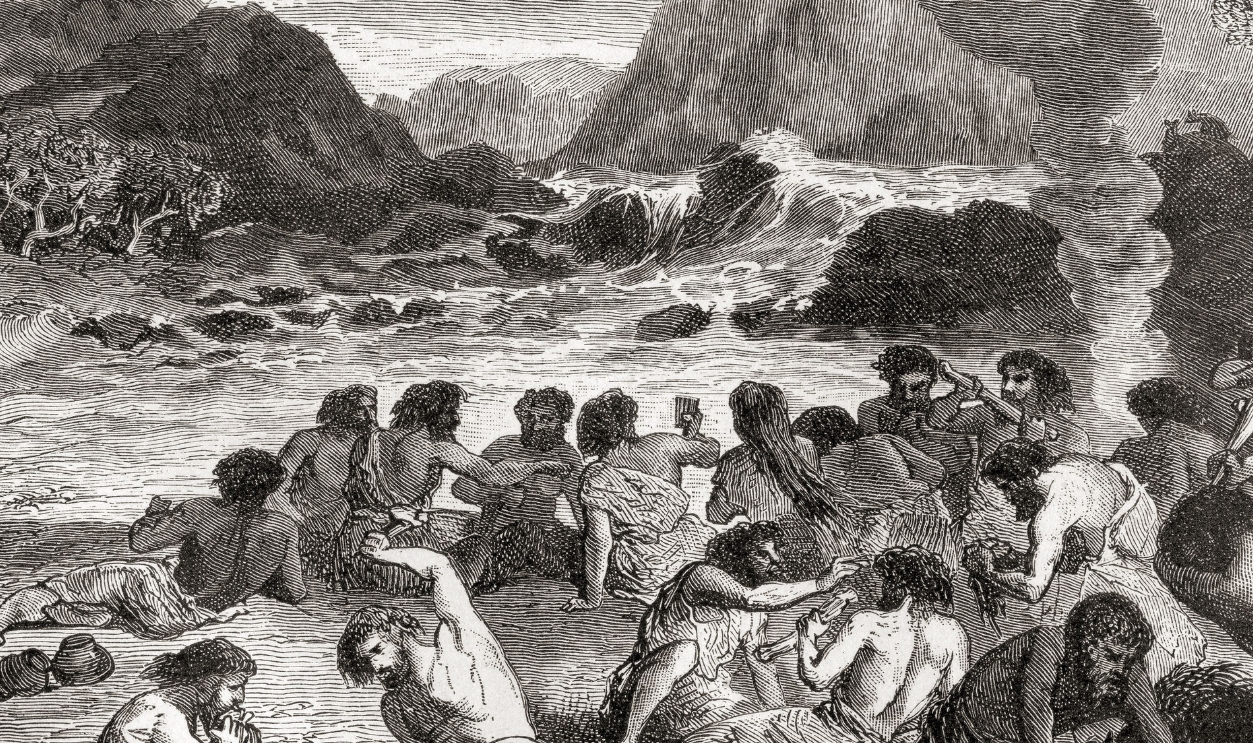

Universal History Archive, Getty Images

Universal History Archive, Getty Images

Why The Findings Still Matter

Understanding these risks helps shape modern ideas about early human resilience. Neanderthals adapted to scarce food and unpredictable fires. Their struggles highlight how far human cooking and safety have progressed and how fragile daily life once felt beneath ancient rock shelters.