The Lake Built For Spectacle

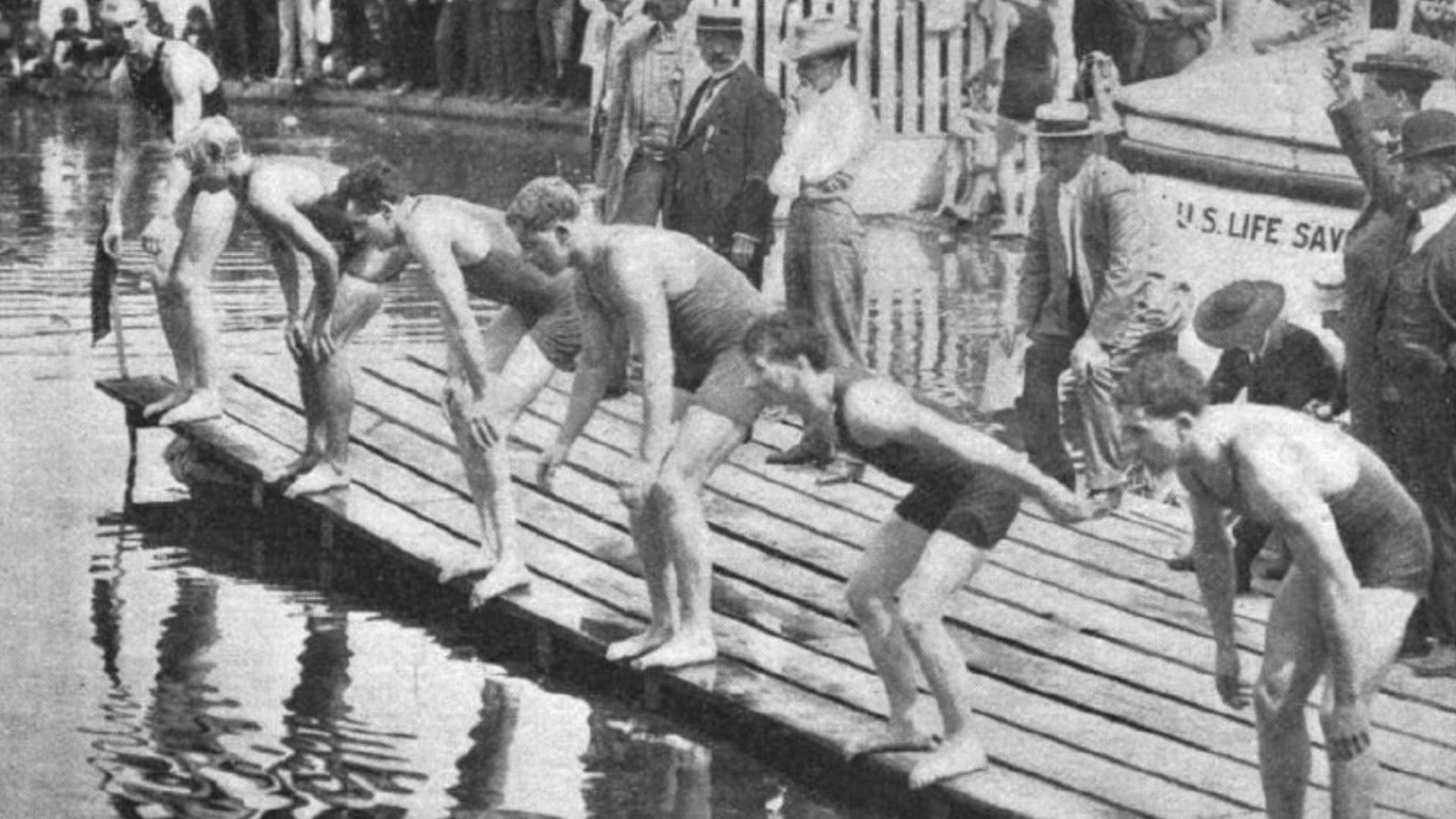

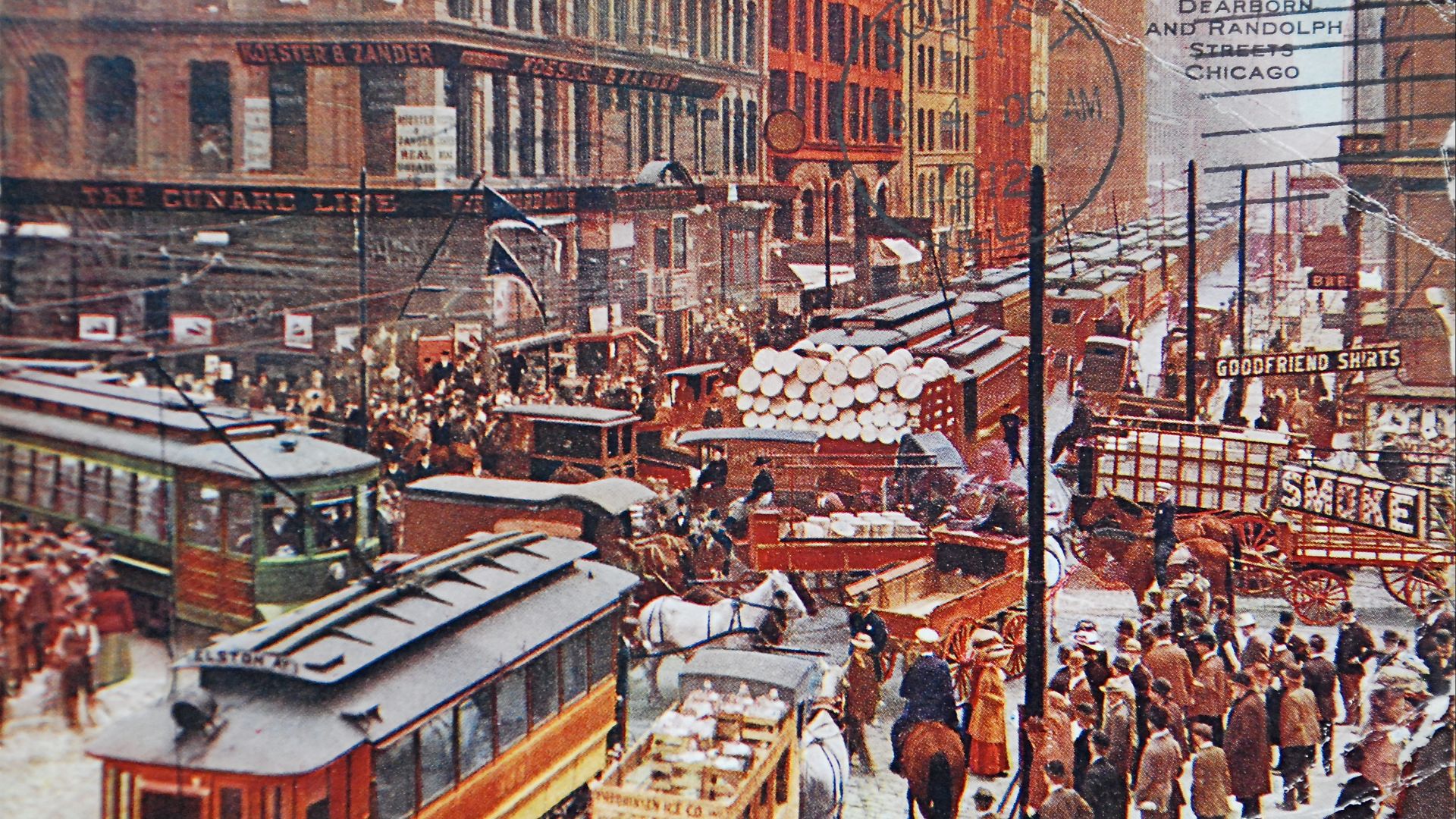

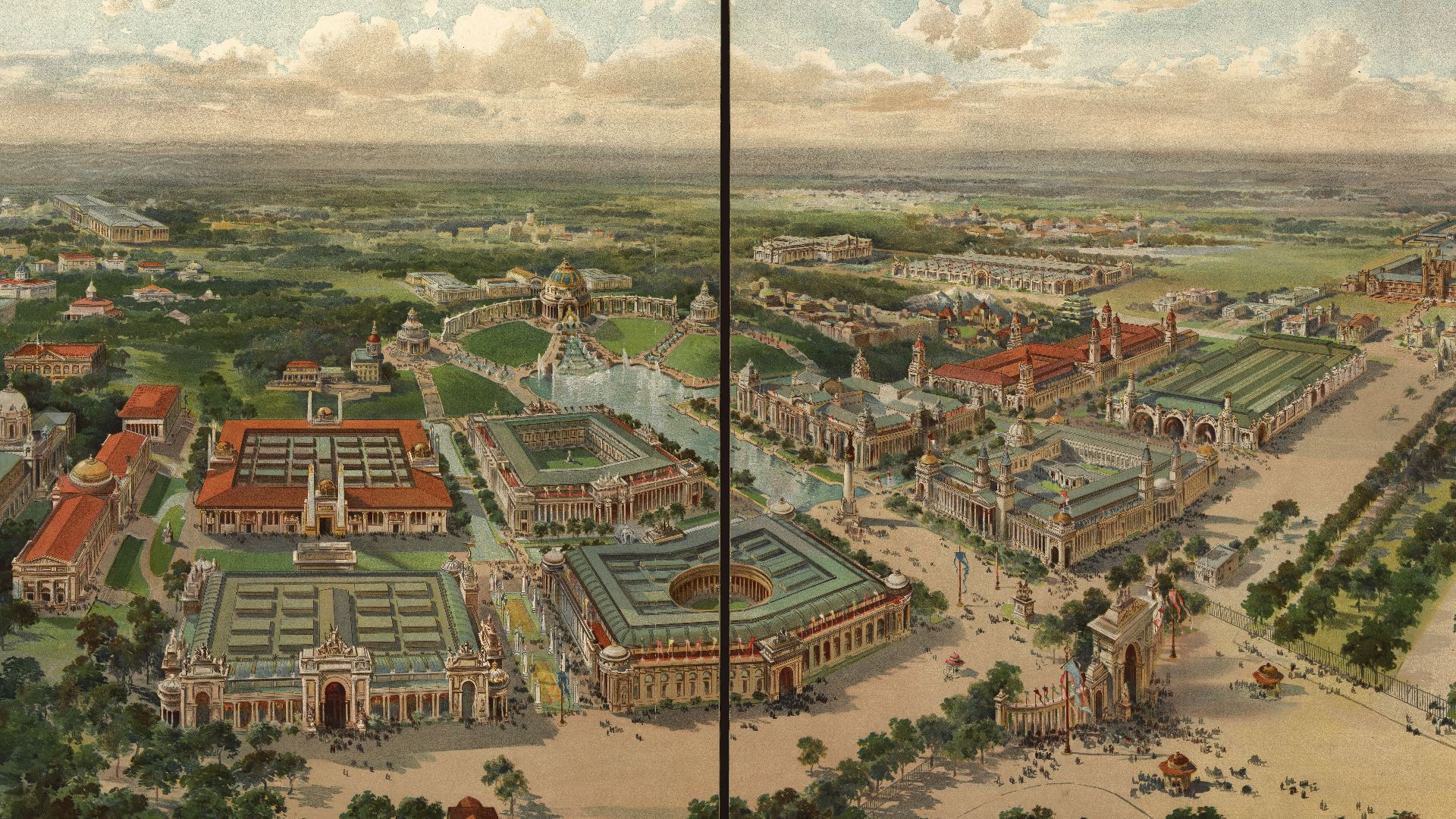

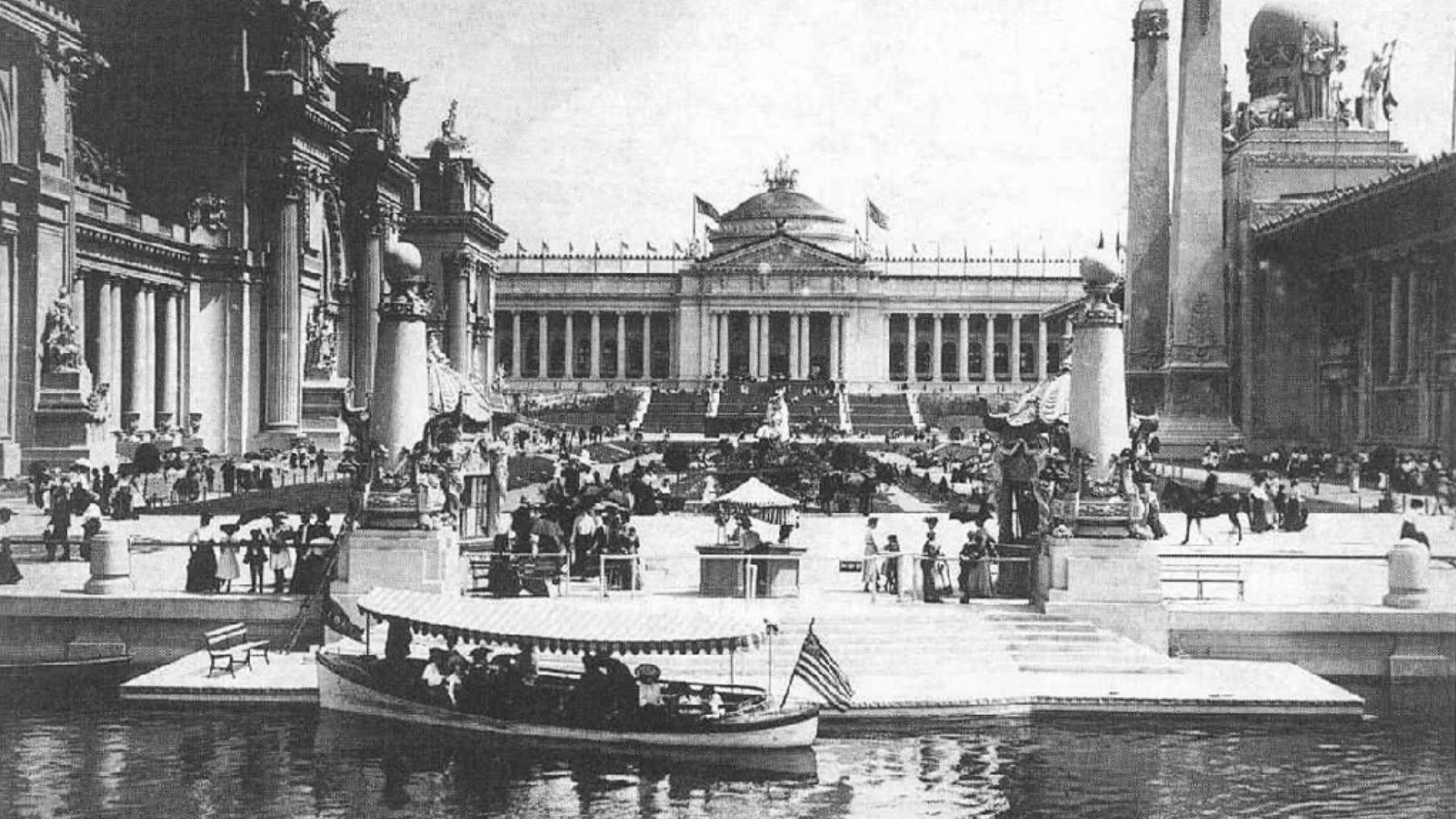

St. Louis in 1904 sold itself as a wonderland: the Louisiana Purchase Exposition—better remembered as the St. Louis World’s Fair—promised modern marvels, crowds, and a kind of curated progress. The Olympic Games were folded into that fairground energy, staged as part of a larger entertainment machine. And for the aquatic events, organizers chose a venue that looked the part: an oval, man-made body of water called the United States Life Saving Exhibition Lake. It was a lake built for demonstration and display. What it wasn’t built for was safety.

A Summer-Olympics Tragedy In A “Winter” Beat

If you cover Olympic tragedy for a living, you learn quickly that the season doesn’t matter. Summer or Winter, the throughline is the same: when sport gets bolted onto spectacle, corners get cut—and bodies pay the bill. The deaths of David Bratton and George Van Cleaf sit in that uncomfortable category: not a collapse on the field of play, not a single catastrophic accident, but a slow, punishing illness whose roots trace back to a choice that should never have been made.

After Camille N. Drie, Wikimedia Commons

After Camille N. Drie, Wikimedia Commons

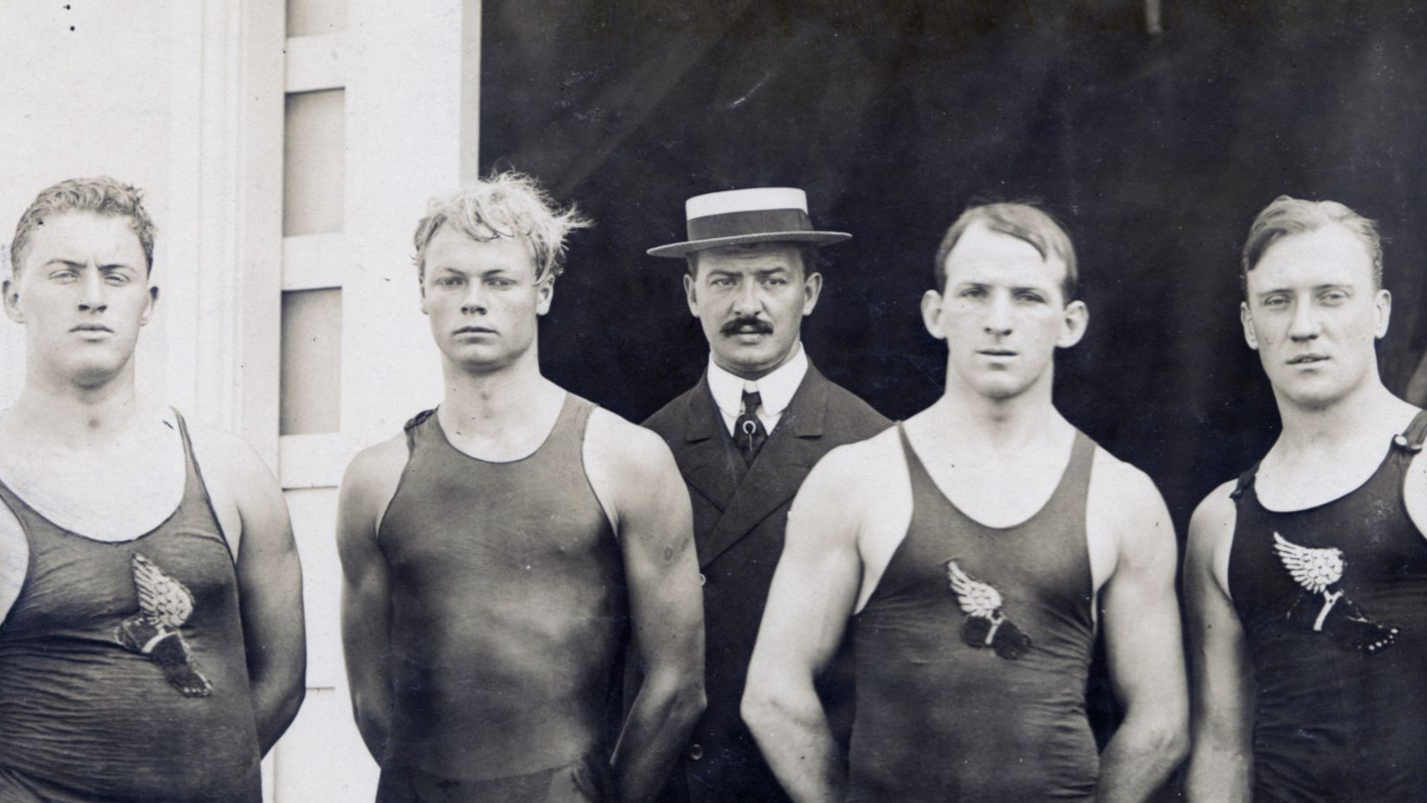

The Athletes Behind The Headlines

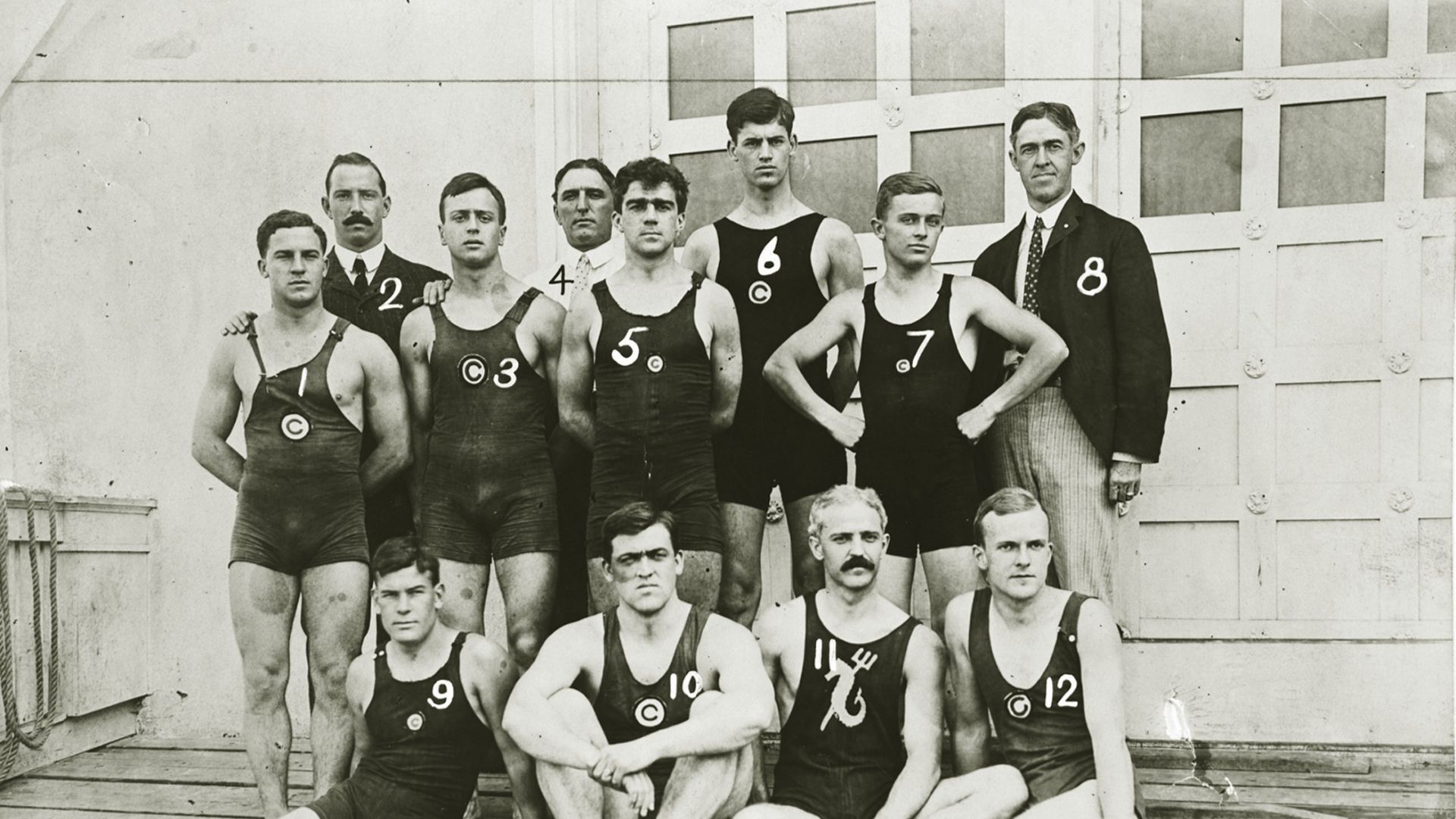

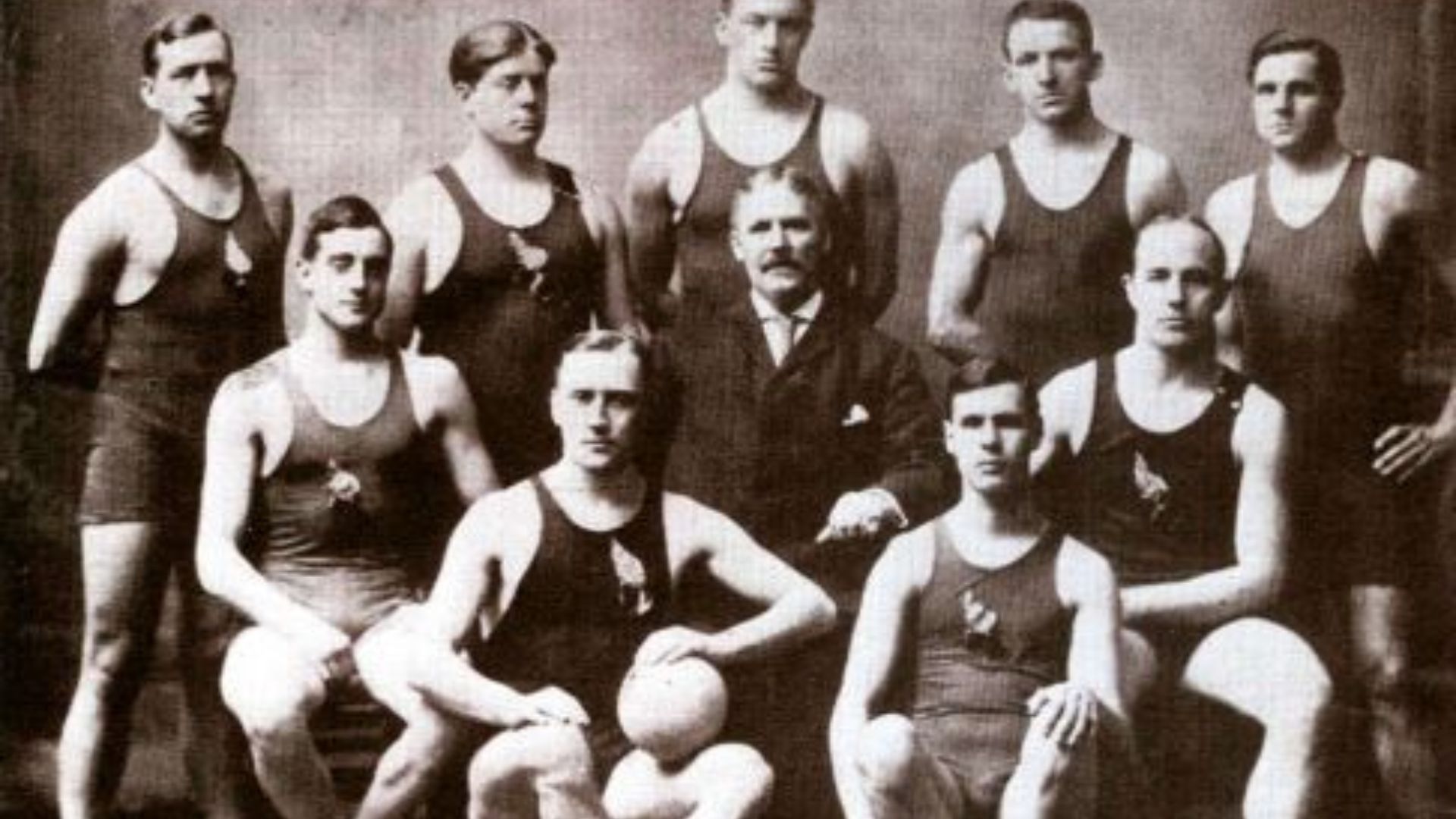

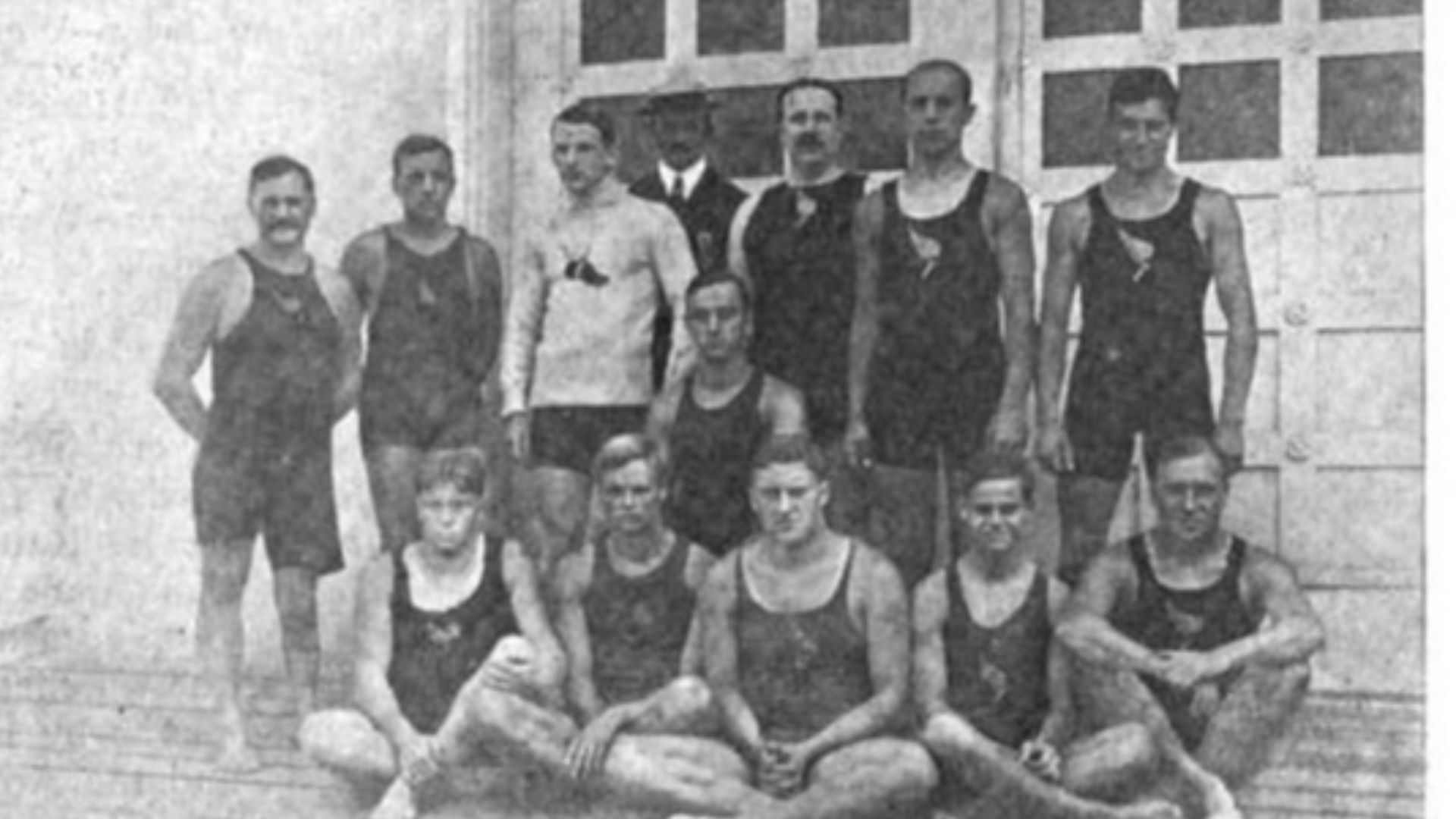

David Hey Bratton and George W. Van Cleaf were not fringe participants passing through. Both were associated with the New York Athletic Club, both competed in the 1904 Olympic water polo tournament, and both were part of the club’s 4x50-yard freestyle relay team. In an era when the United States dominated the medal table largely because the Games were local, they were still legitimate standouts in their aquatic circle—strong enough to make an Olympic roster, proud enough to treat it as a pinnacle.

St. Louis 1904 Was A Different Olympic Planet

No lanes. No starting blocks. No standardized pool. The aquatic program was held in open water, with a floating pontoon dock serving as the start, and a rope line across the water functioning as a finish for some races. The staging was improvised, and the fairgrounds were the real star. The Olympics, at times, felt like a side attraction that happened to include medals. That context matters, because it shaped the most fateful decision of all: where the athletes would swim.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

The “Life Saving Exhibition Lake” Origin Story

The lake had been created to host life-saving demonstrations—practical drills turned into public theater. It sat near major exposition buildings and attractions, positioned for foot traffic and attention. It was, essentially, a prop that could be re-purposed: today a showcase for rescue techniques, tomorrow a stage for Olympic racing. The problem: the lake was stagnant, shallow in the ways that matter, and never engineered as a hygienic athletic venue.

Official Photograph Company, Wikimedia Commons

Official Photograph Company, Wikimedia Commons

An Artificial Lake With Real-World Consequences

By the time the aquatic events began in early September, the fair had been open for months. In that span, accounts describe the lake’s water becoming contaminated by a “variety of toxins,” including manure residues from livestock kept near the Agricultural Building. With no filtration and no purification, the lake functioned like a basin that held onto whatever was introduced into it—sediment, runoff, waste, and heat. For swimmers, that meant repeated immersion, mouthfuls of water, open cuts, and exhaustion—exactly the conditions that turn a bad choice into a health disaster.

Official Photographic Company, Wikimedia Commons

Official Photographic Company, Wikimedia Commons

Livestock Nearby, Sanitation Far Behind

It’s easy to read “manure residues” and picture a simple cause-and-effect: animals nearby, lake polluted, swimmers sick. The reality is more complicated—and arguably worse. Typhoid fever is typically spread through food or water contaminated with feces from infected humans. So livestock waste alone doesn’t neatly explain typhoid outbreaks. But livestock presence can still be part of a broader sanitation breakdown: more waste on site, more runoff risk, more flies, more crowding, more opportunities for contaminated material—human or otherwise—to end up where it shouldn’t.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

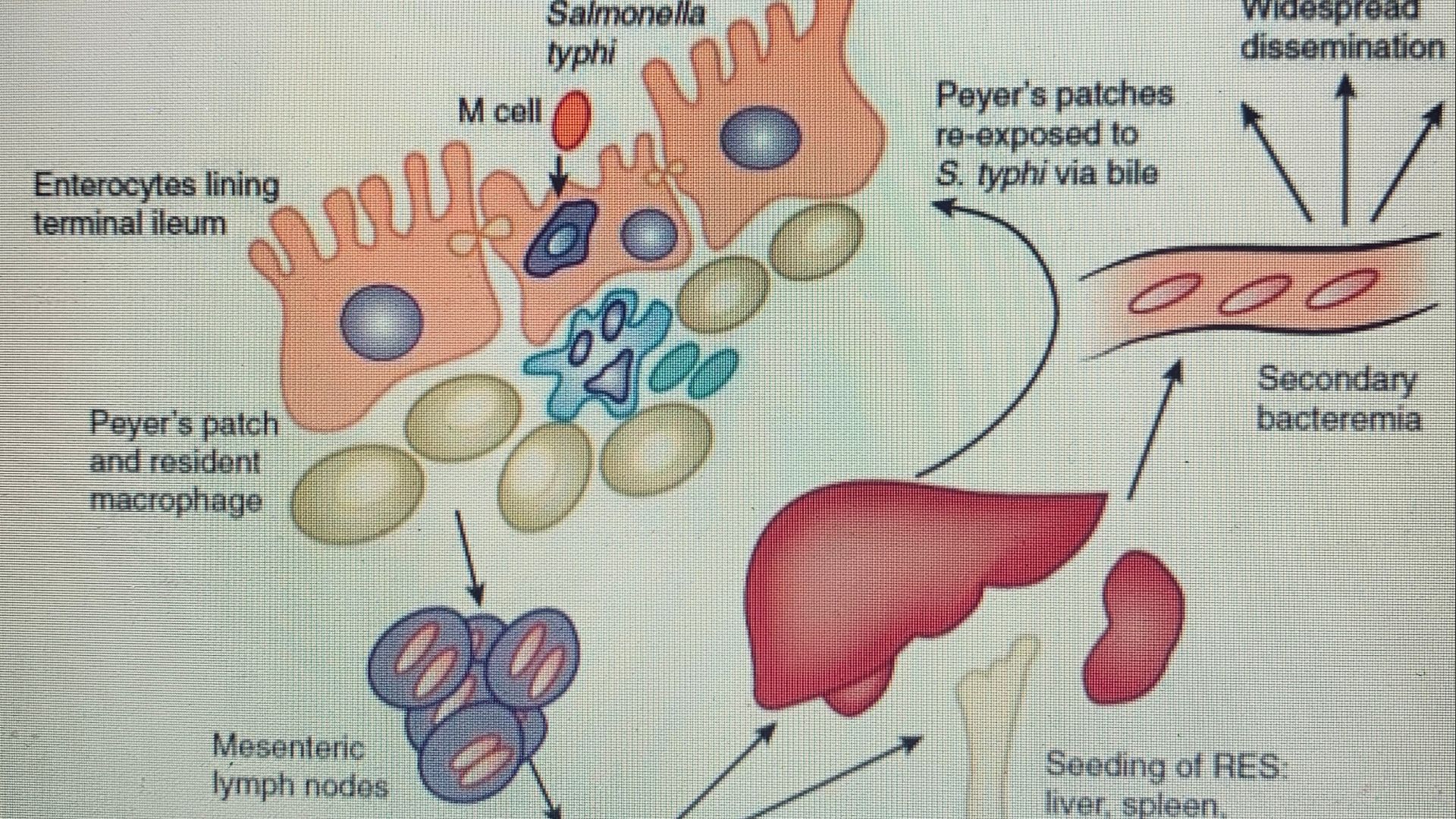

What Typhoid Does To A Body

Typhoid fever is not a dramatic, instant killer. It’s a grind—high fever, weakness, abdominal symptoms, and systemic infection that can spiral into severe complications without effective treatment. In 1904, medicine was transitioning but still limited; antibiotics were decades away, and outcomes could depend on the course of disease, supportive care, and sheer luck. When the infection takes hold, it can feel like the body is being quietly dismantled from the inside.

Microbewriter, Wikimedia Commons

Microbewriter, Wikimedia Commons

The Races Went On Anyway

The athletes swam. They wrestled through water polo matches. They climbed onto that pontoon dock heat after heat. They dove into a lake that looked acceptable from the stands and felt—at least at first—like any other open-water venue. The fair needed its show; the Olympic program needed to be completed; the schedule moved forward. This is the most haunting part of many sports tragedies: nobody has to be malicious for the outcome to be catastrophic. They only have to be willing to proceed.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Illness After The Applause

Reports from historical research describe numerous aquatic participants becoming ill during and after the competitions. That cluster is the signal flare. When multiple athletes fall sick after exposure to a shared environment, the story is no longer about individual misfortune—it’s about systemic failure. And for Bratton and Van Cleaf, the timeline turned from worrying to fatal.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

David Bratton’s Olympic Moment

Bratton left St. Louis as an Olympic gold medalist in water polo. He was also part of the New York Athletic Club relay team that finished fourth. In modern terms, he’d be the kind of athlete celebrated in club halls and local papers—an elite amateur in the era when amateur sport still meant something close to civic pride. He was 35 years old when he died later that year.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

The Speed Of The Decline

Accounts place Bratton’s death in Chicago on December 3, 1904—roughly three months after the St. Louis competitions. That gap matters. It means the Games weren’t just a dangerous afternoon; they were a possible starting gun for an illness that followed him home, took time to bloom, and then overwhelmed him. When people talk about “Olympic legacy,” they don’t usually mean that.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

A Club In Mourning

Bratton’s death didn’t pass quietly inside his athletic community. The New York Athletic Club reportedly cancelled a scheduled swim meet in his honor. It’s a small detail, but it lands hard: a place built around physical prowess forced into the helpless rituals of grief, acknowledging that the champion body can still be fragile—especially when institutions gamble with basic safety.

George Van Cleaf’s Reputation In The Water

Van Cleaf was younger—born in 1879—and by reputation he swam with the kind of hardy bravado that early-century athletes loved to mythologize. Accounts describe him as someone who would get into the water early in the season, as soon as ice cleared. He was, in that sense, built for discomfort, built to endure. That toughness, however, is meaningless against a pathogen.

Jessie Tarbox Beals (attributed), Wikimedia Commons

Jessie Tarbox Beals (attributed), Wikimedia Commons

The Same Team, The Same Lake, The Same Risk

Van Cleaf won Olympic gold in water polo as a member of the New York Athletic Club team, and he, too, was part of the club’s fourth-place relay squad. That overlap with Bratton is the connective tissue of this tragedy: shared club, shared event, shared venue. Not two isolated deaths—two points on the same grim line.

New York Athletic Club, Wikimedia Commons

New York Athletic Club, Wikimedia Commons

Death In January

Van Cleaf died on January 6, 1905. The calendar flipped, the fairgrounds shut down, and the world moved on to the next thing. But typhoid doesn’t care about the page turning. The infection can linger, worsen, and then suddenly end the story. For Van Cleaf, it ended in the winter after his Olympic triumph—months after the lake had been drained of attention, if not of consequence.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

The Phrase “Poisoned Lake” And What It Really Means

It’s tempting—especially in magazine storytelling—to label the venue a “poisoned lake” and stop there. But the more unsettling truth is that “poison” can be mundane. It can be a stagnant basin without filtration. It can be waste management that collapses under crowds and animals and summer heat. It can be officials treating athletes as durable props rather than humans who ingest water and carry microbes home.

The poison, in other words, can be the decision-making.

Official Photographic Company, Wikimedia Commons

Official Photographic Company, Wikimedia Commons

Why This Would Never Fly Today

Modern Olympic aquatic venues are heavily regulated: tested water, controlled circulation, disinfection systems, medical surveillance, and layers of liability that force organizers to take contamination seriously. None of that guarantees safety—nothing does—but it drastically reduces the odds that a venue becomes a disease multiplier.

St. Louis 1904 existed before that learning was paid for in full.

Doma-w (talk), Wikimedia Commons

Doma-w (talk), Wikimedia Commons

The Uncomfortable Role Of Spectacle

World’s Fairs were designed to impress. The Olympics were still finding their identity. Put them together, and you get a strange hierarchy: the fairgrounds’ needs first, the sport second. The lake’s primary purpose wasn’t athlete welfare; it was exhibition value. The athletes, by stepping into that environment, inherited all the invisible compromises baked into the site.

David R. Francis (book author), Wikimedia Commons

David R. Francis (book author), Wikimedia Commons

When Records Burn, Myths Grow

A frustrating footnote of the era is how much documentation has been lost over time, including the destruction of certain records in later years. That loss creates space for mythmaking and simplification—exactly the conditions where tragedy gets reduced to a spooky anecdote rather than a preventable outcome with identifiable causes.

But enough survives to say this much plainly: the venue was contaminated, athletes got sick, and two Olympians died.

Official Photographic Company, Wikimedia Commons

Official Photographic Company, Wikimedia Commons

The Human Cost Of “Good Enough”

Bratton and Van Cleaf didn’t die in the water. They died after. That distance can make the story easier to ignore—until you remember that cause and effect don’t require the same ZIP code. Sometimes “good enough” planning produces “close enough” safety, and the bill arrives later, in a hospital room far from the applause.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

How Their Deaths Changed The Way People Talked

Even if no single policy snapped into place the moment these men died, the narrative of 1904 accumulated into something like a warning label. Historians, Olympic researchers, and sporting bodies have revisited the St. Louis aquatic events precisely because the venue choice reads, now, as indefensible.

Their deaths became part of the evidence file.

New York Athletic Club, Wikimedia Commons

New York Athletic Club, Wikimedia Commons

The Broader Lesson For Olympic Hosts

Every host city insists it can do both: put on a show and protect the people inside it. Often, they can. But when budgets tighten, schedules compress, or leadership is chasing headlines, risk migrates toward those with the least power to object—athletes, workers, and spectators who trust that someone else has checked the water.

St. Louis 1904 is what happens when that trust is misplaced.

Official Photographic Company, Wikimedia Commons

Official Photographic Company, Wikimedia Commons

Remembering Bratton And Van Cleaf As More Than A Footnote

It’s easy to let early-Olympic athletes blur into sepia silhouettes: names in a database, medals in a list, dates on a page. But Bratton and Van Cleaf were living competitors with teammates, training partners, rivalries, and future plans—until an avoidable exposure changed the trajectory.

They deserve to be remembered not only as medalists, but as a case study in what sport owes the people who make it possible.

The Last Image: A Quiet Lake & A Loud Warning

Picture the scene without the crowd: the fairgrounds after hours, the lake’s surface calm, the pontoon dock rocking gently. It looks harmless. That’s the trap. The most dangerous choices in sports history often come dressed as ordinary logistics—just a venue, just water, just a convenient solution. And then two men go home, fall ill, and never recover.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Tragedy Measured In Months, Not Minutes

David Bratton died on December 3, 1904. George Van Cleaf died on January 6, 1905. Their Olympic victories came first; the illness came later; the consequences arrived last—slow enough for denial, fast enough for grief. If you cover Olympic tragedies—Winter, Summer, any season—this story stands out because it isn’t a lightning strike. It’s a chain of preventable decisions, linked together by spectacle, neglect, and a contaminated lake that should never have hosted competition. Their deaths remain a reminder that the Games are never only about what happens on the day of the event, but also about what organizers decide is acceptable risk long before the first whistle blows.

Jessie Tarbox Beals (attributed), Wikimedia Commons

Jessie Tarbox Beals (attributed), Wikimedia Commons

You May Also Like: