A Great Idea

If you looked down on Los Angeles’ largest reservoir, you might think a giant pit of black marbles had swallowed it whole. But those millions of floating balls are no accident—they’re part of a clever solution to a very real problem.

The First Impression

When photos of the “sea of black balls” surfaced online, many assumed it was some kind of art installation. Others joked it looked like a scene from a sci-fi movie. In reality, it’s one of the most unusual public works projects in the U.S.

LA throws 96 million 'shade balls' at its water shortage — and it's mesmerizing | Mashable, Mashable

LA throws 96 million 'shade balls' at its water shortage — and it's mesmerizing | Mashable, Mashable

Meet The Shade Balls

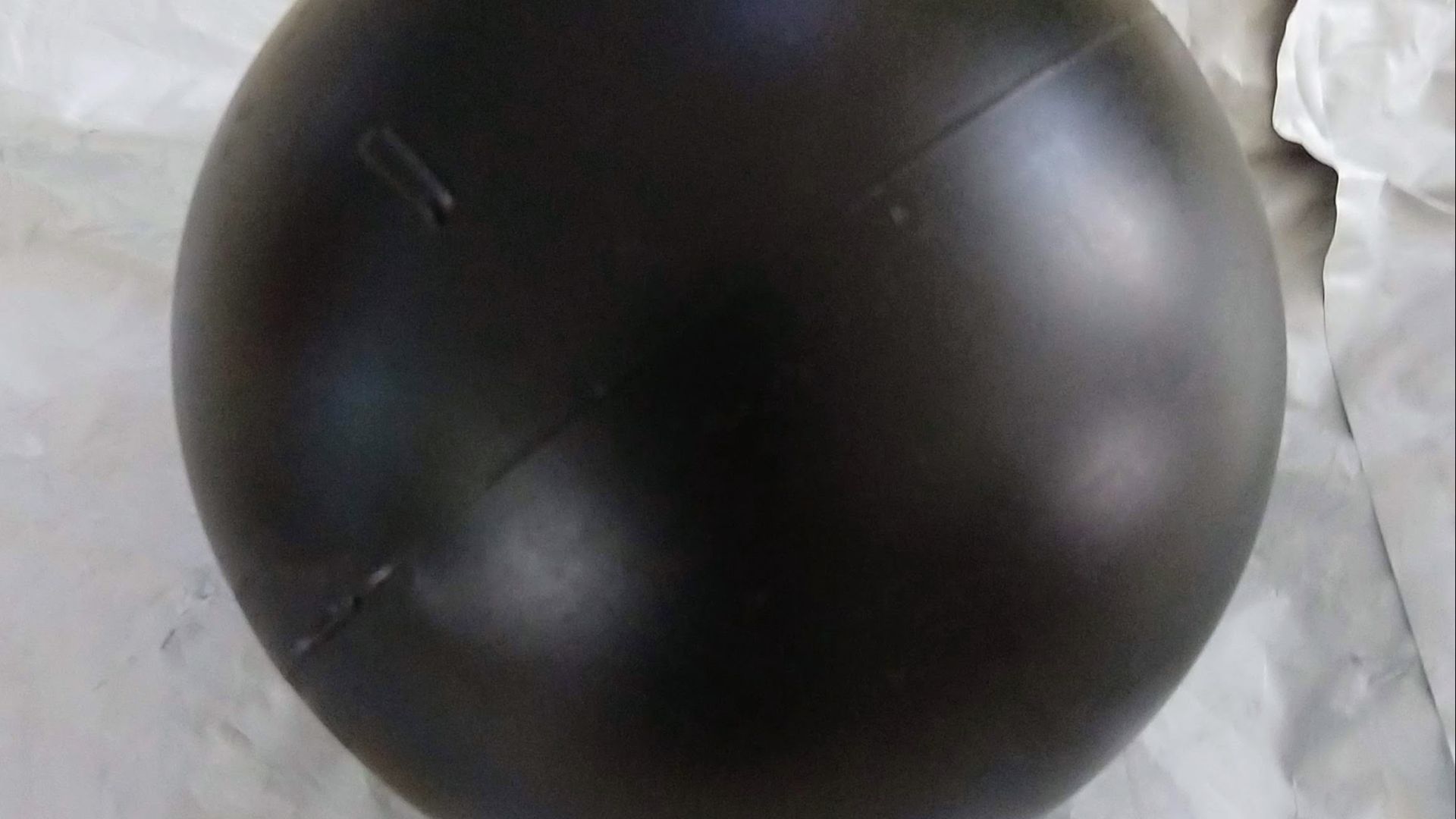

These spheres are called shade balls. They aren’t toys, and they’re not made of rubber—they’re actually crafted from high-density polyethylene (HDPE), a safe, UV-resistant plastic designed to sit in water for years without breaking down.

Harald Bischoff, Wikimedia Commons

Harald Bischoff, Wikimedia Commons

The Chemistry Problem

Back in 2008, Los Angeles officials found a serious issue: sunlight was reacting with chlorine and naturally occurring bromide in open reservoirs. That reaction created bromate, a chemical linked to cancer—and the city needed a fix fast.

Junkyardsparkle, Wikimedia Commons

Junkyardsparkle, Wikimedia Commons

Why Bromate Matters

Bromate is a potential carcinogen, and the EPA sets strict limits in drinking water. By 2008, L.A. was already under pressure to cut levels. As one LADWP official said at the time: “You can’t serve water with bromate in it. End of story.”

Testing At Ivanhoe Reservoir

The first experiment came at Ivanhoe Reservoir in Silver Lake in 2008–2009, when LADWP floated about 400,000 shade balls to reduce bromate. It worked—levels dropped quickly—and the city realized this quirky solution could be scaled up.

Junkyardsparkle, Wikimedia Commons

Junkyardsparkle, Wikimedia Commons

When Covers Cost Too Much

Regulators demanded protection for reservoirs, but traditional covers—like concrete lids or floating membranes—would have cost hundreds of millions and taken years to build. Shade balls, by contrast, could be dumped in by truck and start working overnight.

Junkyardsparkle, Wikimedia Commons

Junkyardsparkle, Wikimedia Commons

How The Balls Work

The concept is simple: cover the water so the sun can’t reach it. No sunlight means no bromate. One water engineer put it memorably: “It’s basically sunscreen for the reservoir.”

Junkyardsparkle, Wikimedia Commons

Junkyardsparkle, Wikimedia Commons

Bonus: Fighting Evaporation

By 2014, California was in a historic drought. Shade balls suddenly gained a second job—cutting evaporation. Los Angeles estimated they saved up to 300 million gallons a year. Some scientists later noted that manufacturing the balls consumed water too, but LADWP argued the savings still outweighed the costs.

AnonymousEditor95, Wikimedia Commons

AnonymousEditor95, Wikimedia Commons

Smart Design Tricks

Each ball is partly filled with water so it won’t blow away. That tiny tweak makes them stable even in strong winds. At about four inches across, they fit together like puzzle pieces, covering 90% of the surface.

Eric Garcetti, Wikimedia Commons

Eric Garcetti, Wikimedia Commons

Made To Outlast The Sun

The balls are coated with carbon black, giving them UV resistance. LADWP estimated a lifespan of 10 years or more, with some claiming up to 25 under ideal conditions. “These are not going to crumble into your drinking water,” the utility reassured the public.

Richard Thomas, Wikimedia Commons

Richard Thomas, Wikimedia Commons

A Bargain Fix

The final rollout cost about $34.5 million, or 36 cents per ball. Pricey, yes—but compared to alternatives costing hundreds of millions, it was a bargain. And the water savings, plus cleaner supply, added to the payoff.

A Mind-Bending Scale

By 2014–2015, Los Angeles had ordered nearly 96 million shade balls to cover 175 acres of water. From the air, it looked like a massive black carpet—what one reporter called “the world’s largest ball pit, just not for kids.”

Eric Garcetti, Wikimedia Commons

Eric Garcetti, Wikimedia Commons

The Big Moment In 2015

The final deployment came in August 2015, when Mayor Eric Garcetti and LADWP officials watched trucks dump the last 20,000 balls into the Los Angeles Reservoir. “Today we take another step to secure L.A.’s water future,” Garcetti said.

Eric Garcetti, Wikimedia Commons

Eric Garcetti, Wikimedia Commons

The Internet Reaction

That 2015 event went viral. Videos of the black spheres rolling across the water racked up millions of views. Online, people compared it to an alien invasion, a Hollywood set piece, even “a giant bowl of caviar.”

Junkyardsparkle, Wikimedia Commons

Junkyardsparkle, Wikimedia Commons

Copycats Around The World

After L.A.’s splashy debut, other regions began testing shade balls—sometimes in water treatment plants, sometimes in mining or agriculture. Anywhere with lots of sun and scarce water, the idea looked appealing.

Scott L from Los Angeles, United States of America, Wikimedia Commons

Scott L from Los Angeles, United States of America, Wikimedia Commons

Keeping Things Cleaner

Shade balls don’t just block sunlight. They keep out dust, bird droppings, and algae growth. That meant cleaner water with fewer chemicals needed downstream. One LADWP official joked they were “our cheapest employees—working 24/7 without overtime.”

Pop Culture Fame

For a while, shade balls had their 15 minutes of fame. They popped up in late-night monologues, memes, and tourist chatter. As one commentator laughed: “Only in L.A. would we fight cancer and drought with a giant ball pit.”

Why Are 96,000,000 Black Balls on This Reservoir?, Veritasium

Why Are 96,000,000 Black Balls on This Reservoir?, Veritasium

Not Without Critics

Some environmentalists raised eyebrows. Would producing 96 million plastic balls leave too big a footprint? Was the water used in manufacturing worth the savings? These questions made headlines even as the balls floated peacefully.

Why Are 96,000,000 Black Balls on This Reservoir?, Veritasium

Why Are 96,000,000 Black Balls on This Reservoir?, Veritasium

The City’s Response

LADWP countered that the balls were recyclable and safe, and that the overall net benefit was in L.A.’s favor. “The tradeoff is overwhelmingly positive,” one spokesperson told reporters.

Eric Garcetti, Wikimedia Commons

Eric Garcetti, Wikimedia Commons

A Three-In-One Fix

Shade balls checked three boxes at once: they cut bromate risk, reduced evaporation, and kept the water cleaner. Few infrastructure projects can claim such a wide range of benefits in one swoop.

Junkyardsparkle, Wikimedia Commons

Junkyardsparkle, Wikimedia Commons

Strange But Brilliant

At first glance, the idea looked bizarre. But by 2015, it had proven itself. The weirdest-looking fix turned out to be one of the smartest public health moves Los Angeles ever made.

Why Are 96,000,000 Black Balls on This Reservoir?, Veritasium

Why Are 96,000,000 Black Balls on This Reservoir?, Veritasium

Still Floating Strong

Years later, the shade balls are still doing their job on the Los Angeles Reservoir. At other reservoirs like Ivanhoe, they were eventually removed to meet federal cover rules. But on the city’s largest reservoir, they remain—quietly protecting L.A.’s water since 2015.

Why Are 96,000,000 Black Balls on This Reservoir?, Veritasium

Why Are 96,000,000 Black Balls on This Reservoir?, Veritasium

You Might Also Like:

American "Secret Spots" That Locals Won't Talk About (And Tourists Shouldn't Ask)

Countries That Are Considering Closing Their Doors To Tourists