Returning To The Light

The Selk'nam people were once plentiful in the Patagonia region. However, by 1930 there were barely 100 Selk'nam people left. Who were the Selk'nam? What happened to them and how have they returned today?

Traditional Life

Traditionally, the Selk’nam were nomadic, traveling around the Patagonian region of Southern Argentina and Chile. This includes the Tierra del Fuego islands. They used their skill and knowledge of the land to survive.

Traditional Life

Their primary source of food was hunting, but when low tides allowed, they would fish as well. However, they had competition within the area.

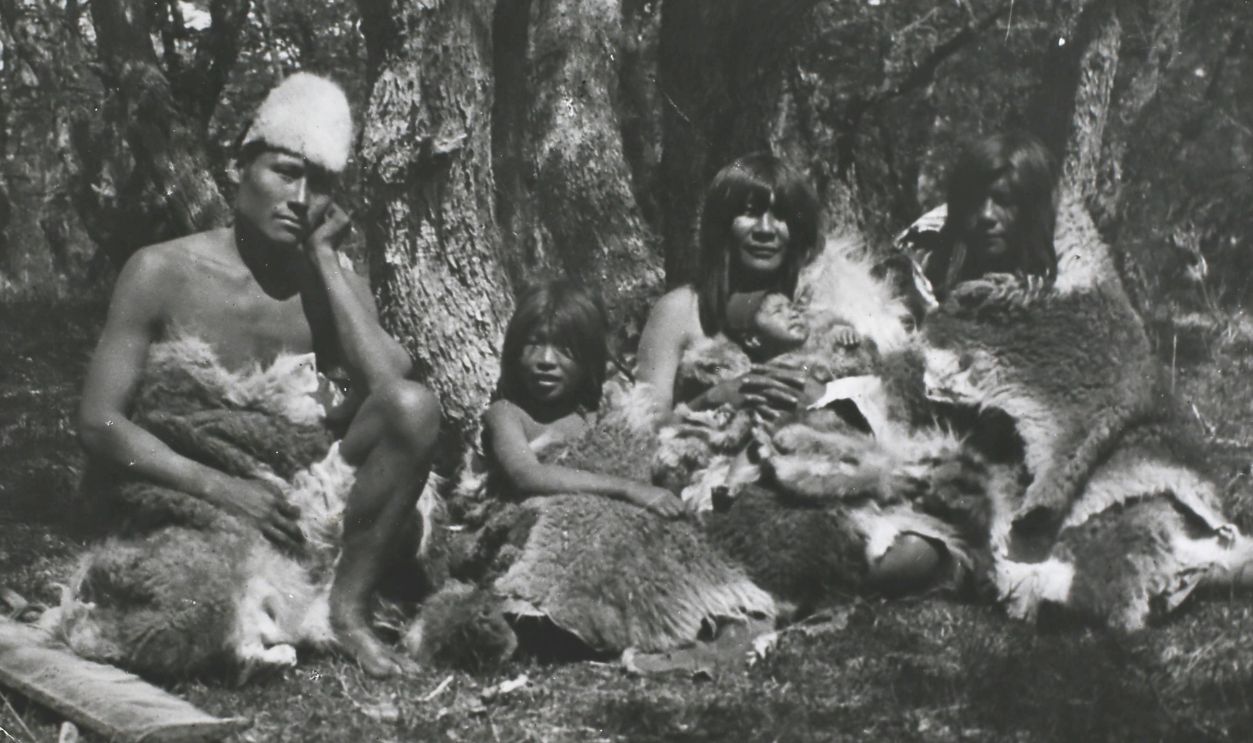

Alberto Maria de Agostini (1883-1960), Wikimedia Commons

Alberto Maria de Agostini (1883-1960), Wikimedia Commons

The Local Tribes

The Selk’nam were not the only nomadic tribe in the Patagonia region. They shared Tierra del Fuego with two other groups: the Haush and the Yahgan. Yet, it was the Europeans that disrupted their lives entirely.

William Singer Barclay, Wikimedia Commons

William Singer Barclay, Wikimedia Commons

European Introduction

During the 19th century, European powers were making rapid progress across the globe, claiming more and more land as their own. The Selk’nam people managed to hold off their fate for some time; they were among the last native groups in South America to be “discovered” by Europeans. It only delayed the inevitable.

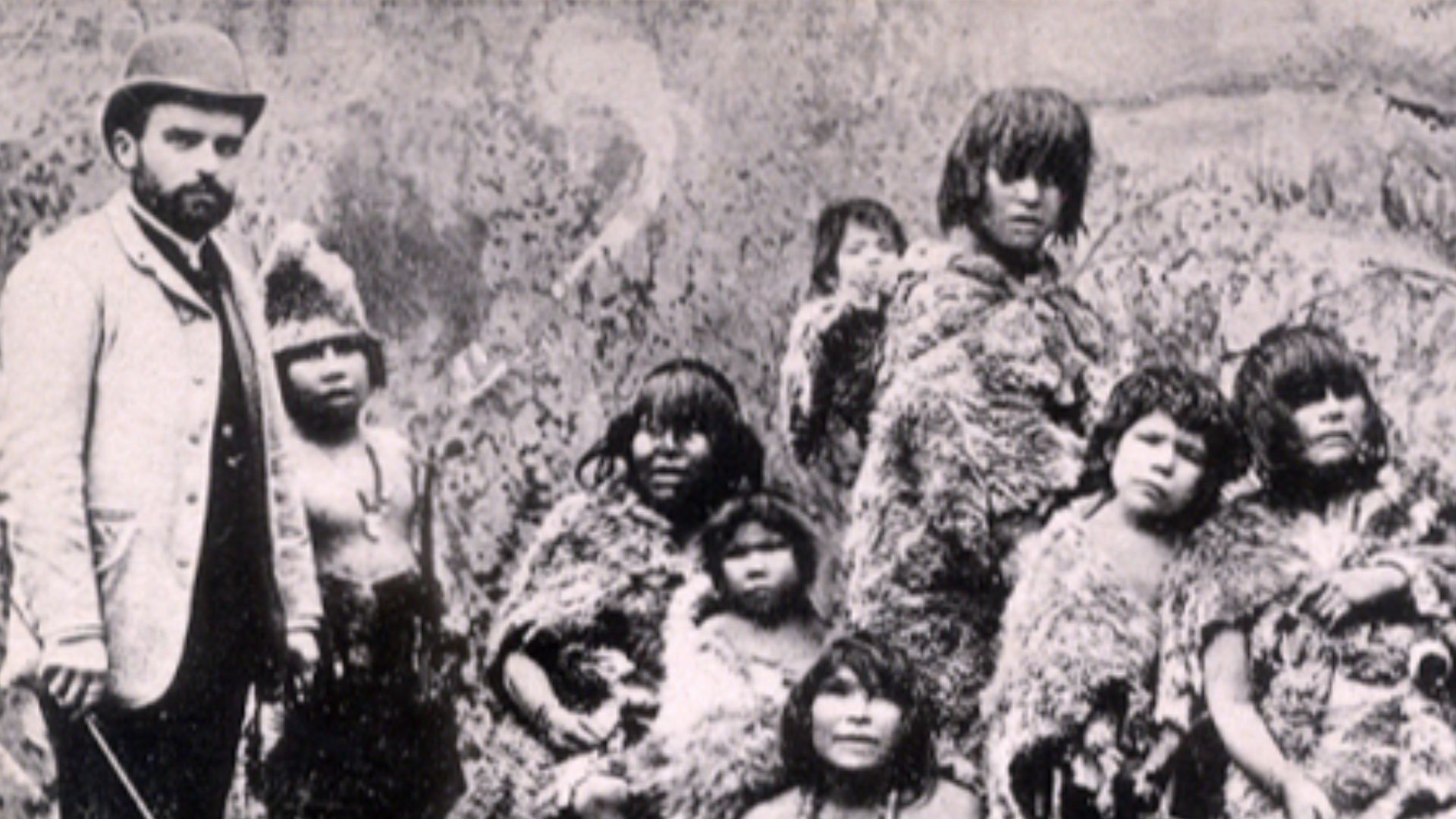

Adolfo Kwasny, Punta Arenas, Chile., Wikimedia Commons

Adolfo Kwasny, Punta Arenas, Chile., Wikimedia Commons

European Introduction

The Selk’nam first encountered Europeans in 1599. Oliver van Noort led a Dutch fleet into the Strait of Magellan which separated Tierra del Fuego from the mainland. There, he encountered Selk’nam people—it did not go well.

Jan Arkesteijn, Wikimedia Commons

Jan Arkesteijn, Wikimedia Commons

European Introduction

The encounter between van Noort’s fleet and the Selk’nam was the most devastating exchange recorded in the famed strait up until that point. About 40 Selk’nam perished in the conflict. The tragedy would only continue as more Europeans entered their lands.

Olivier van Noort, Wikimedia Commons

Olivier van Noort, Wikimedia Commons

European Introduction

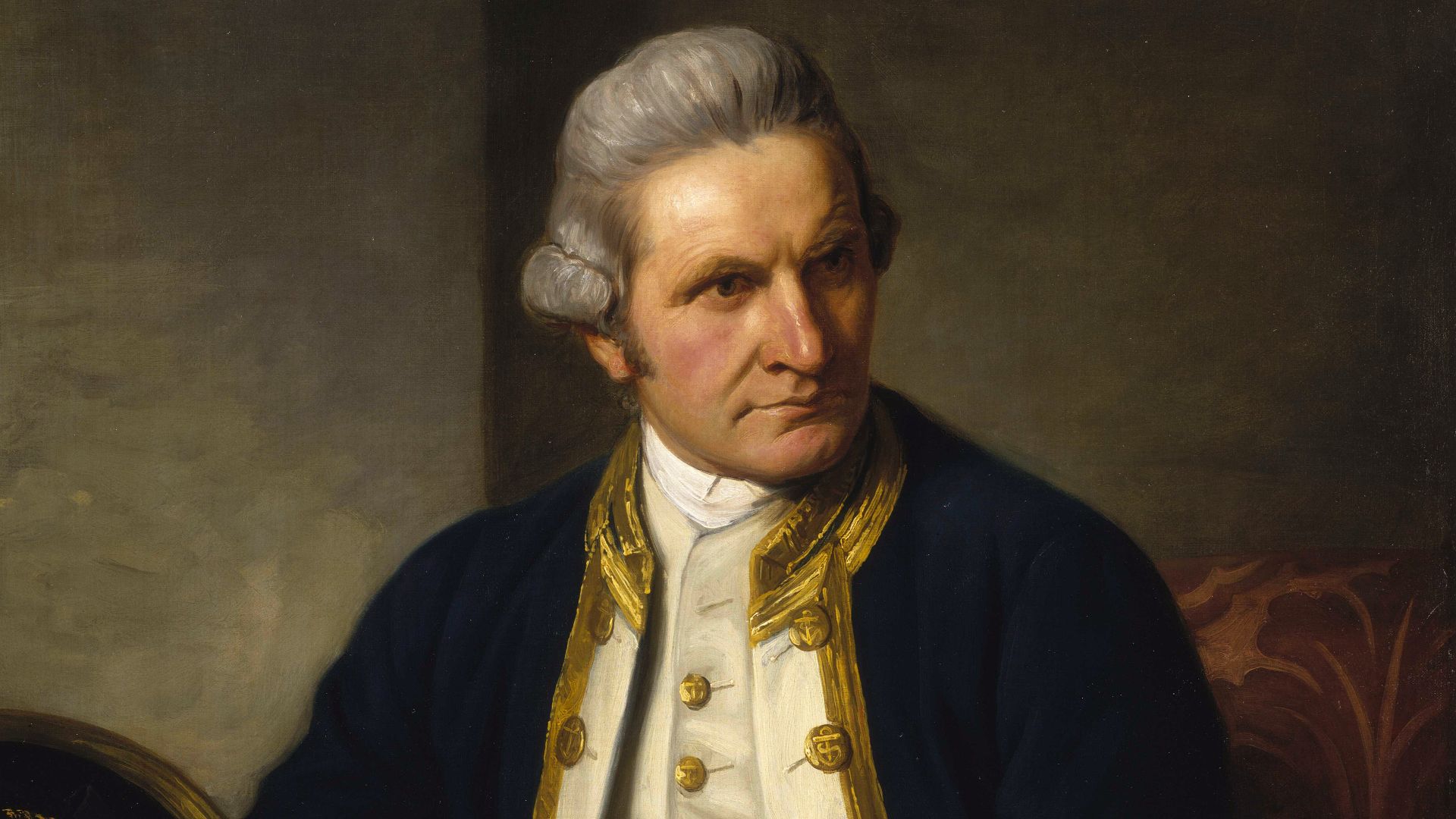

Another meeting likely occurred in 1769. James Cook described an encounter with a people in Tierra del Fuego who used pieces of glass in their arrowheads. Believing that the glass was a gift from Louis Antoine de Bougainville, a French explorer, he felt it was indicative of several earlier contacts.

Nathaniel Dance-Holland, Wikimedia Commons

Nathaniel Dance-Holland, Wikimedia Commons

The Ranchers

The Selk’nam were fortunate enough to avoid much contact with Europeans until the late 19th century. At this point, the so-called settlers began claiming and developing large parts of Tierra del Fuego, leading to problems.

Se desconoce el nombre del fotografo., Wikimedia Commons

Se desconoce el nombre del fotografo., Wikimedia Commons

The Ranchers

The newcomers turned the lands into large ranches, primarily raising sheep. This significantly cut into the Selk’nam’s traditional hunting land. However, there was a bigger problem.

Jorge Láscar from Australia, Wikimedia Commons

Jorge Láscar from Australia, Wikimedia Commons

The Ranchers

“Private property” was not a concept that the nomadic Selk’nam had. They viewed the land and the creatures upon it as communal resources to be had for all. When the Europeans turned up with their ranches, they saw this land the same as they always had.

Furlong, Charles Wellington, Wikimedia Commons

Furlong, Charles Wellington, Wikimedia Commons

The Ranchers

The Selk’nam didn’t view or understand that the Europeans “owned” the sheep. They hunted them as they would have any wild animal that roamed their hunting lands. The Europeans did not take kindly to this.

writtecarlosantonio, Wikimedia Commons

writtecarlosantonio, Wikimedia Commons

The Ranchers

To the Europeans, the Selk’nam were poachers. They were stealing their private property by hunting their sheep. As a result, the ranch owners hired groups to hunt and remove the Selk’nam.

The Eradication Of The Selk’nam

Now referred to as the Selk’nam genocide, this approved hunting of the Selk’nam people by the ranchers, and even the Chilean and Argentine governments, is acknowledged as responsible for the attempted eradication of the Selk’nam people. They nearly succeeded.

Unknown author., Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author., Wikimedia Commons

The Eradication Of The Selk’nam

The hunting forced the remaining Selk’nam people to flee to the southern portion of the island. This area was forested and not suitable for livestock; the Salesians of Don Bosco, a Catholic group, were eventually given grants to “save” the Selk’nam.

The Eradication Of The Selk’Nam

The remaining Selk’nam were sent to Dawson Island; the Salesian missionaries' attempt to “save” the Selk’nam amounted to collecting them on the island and teaching them to assimilate into the new European-Chilean culture.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

The Southern Groups

In the southern region of the island, around the Beagle Channel, the relationship between settlers and the Selk’nam people was slightly better. Thomas Bridges, an Anglican missionary, was granted a large portion of land in the area. Bridges appeared somewhat more willing to coexist with the original inhabitants.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

The Southern Groups

Bridges established Estancia Harberton. His son, Lucus Bridges, attempted to provide the local people with space to live their traditional lifestyle. Unfortunately, the tides of change were too great for the Bridges or the Selk’nam people to fend off.

Claudio Elias, Wikimedia Commons

Claudio Elias, Wikimedia Commons

The Fall Of The Selk’nam

On top of hunting and removing them from their traditional lands, widespread European diseases also dwindled the numbers of the Selk’nam people. Their people were rapidly fading from the world.

The Fall Of The Selk’nam

In the mid to late 1800s, records estimate that the Selk’nam people numbered anywhere from 3,000-4,000. Throughout the 20th century, thanks to European involvement, that number rapidly decreased.

Martin Gusinde, Wikimedia Commons

Martin Gusinde, Wikimedia Commons

The Fall Of The Selk’nam

In 1919, only 20 years after an estimate numbered their people at 3,000, it was reported that there were only 279 left. That number dropped further; in 1945, a Salesian missionary reported only 25 Selk’nan people.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

The Fall Of The Selk’nam

In May 1974, the Selk’nam people faced a particularly significant loss. Angela Loij passed. She was the last known Selk’nam of non-mixed ancestry. However, all hope for the Selk’nam was not lost.

Anne Chapman, Wikimedia Commons

Anne Chapman, Wikimedia Commons

The Rise Of The Selk’nam

In the 1980s, a group was formed to fight for the recognition and rights of Selk’nam in Argentina. In 1994, they had a major win: the government recognized them as an Indigenous people. This was just the first step in restoring their community.

ArchivoCTDHFenix, Wikimedia Commons

ArchivoCTDHFenix, Wikimedia Commons

The Rise Of The Selk’nam

In 1998, the powers that be recognized a treaty signed in 1925 between Argentina and the Selk’nam people. A law was passed, restoring 35,000 hectares of the 45,000 hectares of land designated in the original treaty to the Selk’nam people.

Víctor Bugge, Wikimedia Commons

Víctor Bugge, Wikimedia Commons

The Rise Of The Selk’nam

Slowly, the people themselves were returning as well. The 2010 National Population Census of Argentina showed promising numbers. 2,761 people identified as Selk’nam throughout the country. A similar movement is growing within Chile as well.

Selk’nam In Chile

The 2017 Chilean census also marked a rise in numbers. It showed 1,144 people who recognized themselves as Selk’nam. At the time, they were considered extinct by the Chilean government; they had something to say about that.

picture alliance, Getty Images

picture alliance, Getty Images

Selk’nam In Chile

A group called the Corporacion Selk’nam successfully campaigned for an amendment to Chile’s Indigenous laws. In June 2020, the Chilean government passed a law that officially recognized them as Indigenous peoples of Chile.

Chile Indigenous groups demand recognition, Al Jazeera English

Chile Indigenous groups demand recognition, Al Jazeera English

Selk’nam In Chile

Further success was made in 2023. At this point, the National Congress of Chile recognized the Selk’nam as one of the 11 original peoples of Chile. They also issued a statement of regret over the role the state played in the devastation of Indigenous people.

The Selk’nam Traditions

Despite the mass eradication of their people and their traditions, there still exists a fair amount of information about how the Selk’nam people traditionally lived. They may provide a road back to a modern form of those lost ways.

Chile Indigenous groups demand recognition, Al Jazeera English

Chile Indigenous groups demand recognition, Al Jazeera English

Hunting And Fishing

The Selk’nam were hunters. Much of their diet consisted of the local wildlife, particularly the guanaco. The guanaco is an animal native to the region that closely resembles the llama. This was what the Selk’nam primarily hunted.

Paul Asman and Jill Lenoble, Wikimedia Commons

Paul Asman and Jill Lenoble, Wikimedia Commons

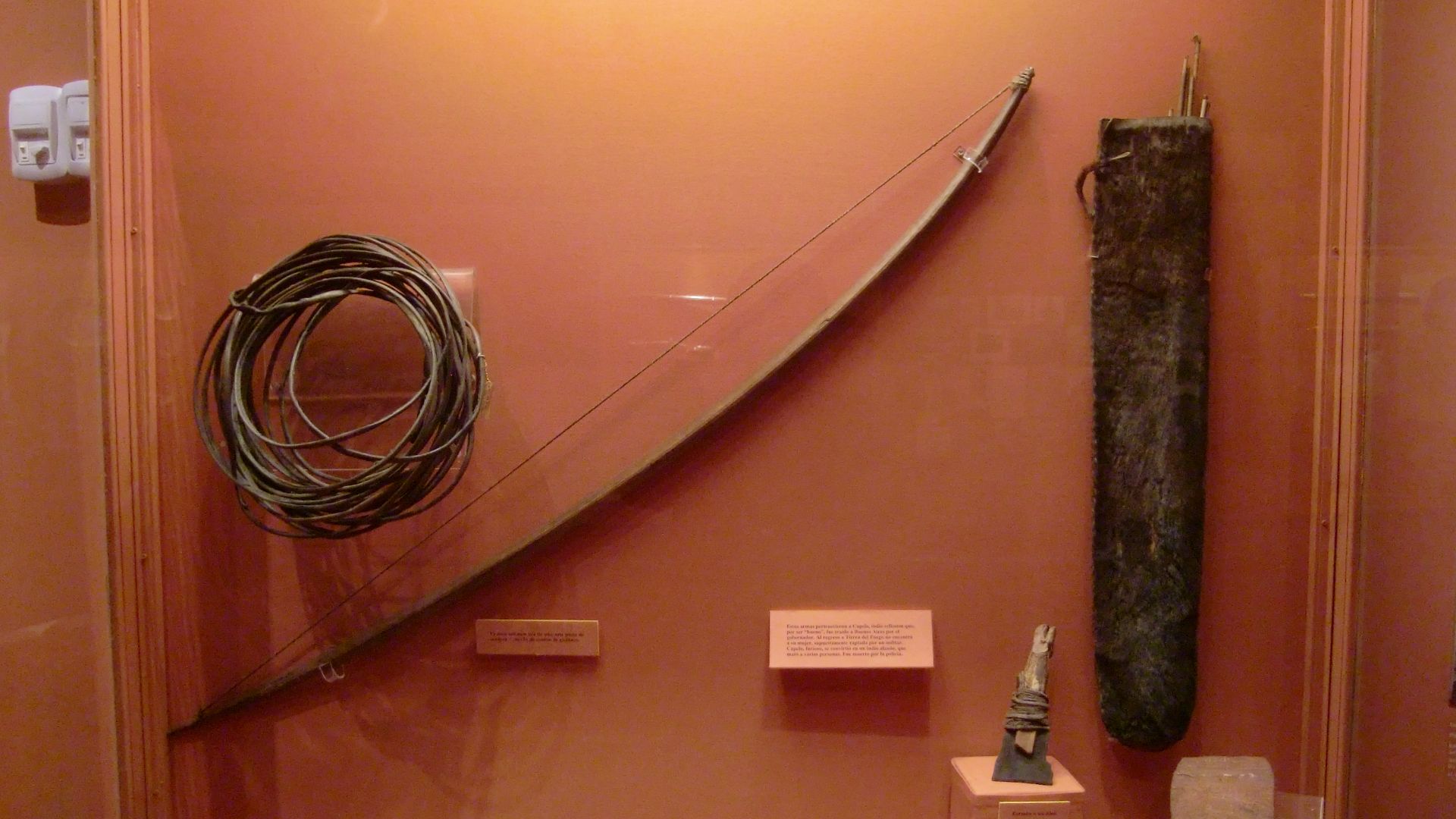

Hunting And Fishing

The Selk’nam typically hunted their prey with bows and arrows. As with many native cultures throughout the world, they did not waste their resources. The guanaco hides were used for shelter, bags, and clothing.

WereSpielChequers, Wikimedia Commons

WereSpielChequers, Wikimedia Commons

Hunting And Fishing

Fishing was another source of food. However, it could only be done during low tide as they engaged in spearfishing only. They typically caught eels, though they occasionally caught fish called robalos as well.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Hunting And Fishing

The Selk’nam people also used a domesticated form of the culpeo fox during their hunts. Referred to as the Fuegian dog, they were not always used but enough evidence supports their use in some tribes and hunts. They had another purpose, too.

Thomas Fuhrmann, Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Fuhrmann, Wikimedia Commons

Hunting And Fishing

The sources agree that the dogs also provided a means of staying warm. When in their shelters, the dogs would sleep tightly against and around the Selk’nam, providing additional warmth in the cold southern climate.

Leon-Louis Chapon, Wikimedia Commons

Leon-Louis Chapon, Wikimedia Commons

The Selk’nam Language

Their language was part of the Chon language family. Although the missionary Jose Maria Beauvoir compiled a dictionary of the language, few, if any, fluent speakers exist today. One source states that the last fluent native speaker passed in the 19080s.

The Selk’nam Religion

As with many cultures, the Selk’nam had a rich and complex system of beliefs. They had their own creation myth and this fed into their traditions, including the Hain, the male initiation ceremony.

The Selk’nam Rites

When men in Selk’nam communities reached a certain age, they were initiated into adulthood through a specific ceremony that marked their step into the world of adults. It was a unique ceremony that drew on their beliefs.

The Selk’nam Rites

Selk’nam children were taught to fear certain “spirits” as a means to behave. When young men reached a certain age, they were brought to a dark hut where they were attacked by these spirits. Their goal was to realize that these spirits were actually human.

Template:Padre Alberto de Agostini, SDB, Wikimedia Commons

Template:Padre Alberto de Agostini, SDB, Wikimedia Commons

The Selk’nam Rites

Traditionally, a Hain could last months if not a year. The men would go through various tests which were designed to teach them skills necessary for life. They’d often start when food was plentiful to support the gathering of the entire community.

DEA PICTURE LIBRARY, Getty Images

DEA PICTURE LIBRARY, Getty Images

The Selk’nam Adornment

The Selk’nam painted their faces and bodies for important occasions, such as the Hain, weddings, and funerals. Like the Hain, both wedding and funerals had their traditions as well.

Pehuén Editores Pehuen Editores, Wikimedia Commons

Pehuén Editores Pehuen Editores, Wikimedia Commons

The Selk’nam Marriage

To propose in a traditional Selk’nam society, the man in question needed to have a bow made. Once done, he would present it to the woman he wished to marry in front of the elders of her family. The end of life had its rights, too.

The Selk’nam Funeral

Funerals were large affairs for the Selk’nam. When one passed, their family would light a fire where they’d sing and dance. They would then wrap the departed in a guanaco cape and bury them as soon as possible.

You May Also Like:

Photos Of The Fearsome Nomadic Tribe Roaming Kenya

The Untold Story Of The Ainu People, Japan’s Forgotten Tribe