A Scientific Breakthrough

In October 2025, scientists published groundbreaking research in Geophysical Research Letters. A volcano in Iran that hadn't erupted in 700,000 years was moving now. The ground was swelling, and it could disrupt the findings.

The Forgotten Giant

Taftan volcano towers 12,927 feet above southeastern Iran's desert area. This massive stratovolcano sits near the Pakistan border, crowned with twin peaks coated white from sulfur deposits. For decades, scientists barely noticed it, and it was labeled as dormant.

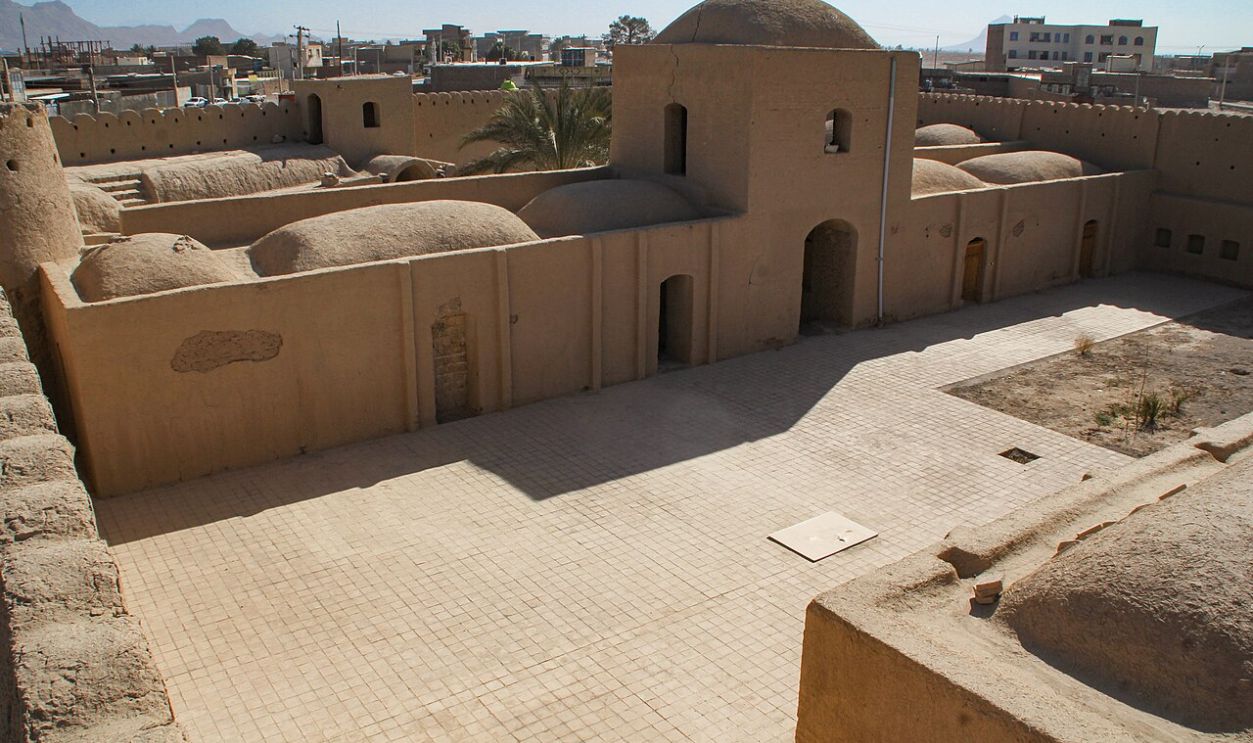

Safa.daneshvar, Wikimedia Commons

Safa.daneshvar, Wikimedia Commons

Where Two Plates Collide

It exists because of a slow-moving collision deep beneath Iran. The Arabian Plate slides beneath the Eurasian Plate at about 1.4 inches per year. The ongoing movement formed the Makran volcanic arc—a fiery chain along the coast where molten rock gradually rises toward the surface.

A Remote And Dangerous Location

The mountain sits in Sistan and Baluchestan Province, one of Iran's most isolated regions. Border conflicts with Pakistan simmer constantly. The nearest city, Khash, lies 31 miles away. This remoteness explains why scientists rarely visited or studied this volcano closely.

Dolphinphoto5d, Wikimedia Commons

Dolphinphoto5d, Wikimedia Commons

Why Border Conflicts Matter

In January 2024, Iran launched missile strikes into Pakistan's Balochistan region—the same area near Taftan. Ongoing territorial tensions and security concerns make scientific fieldwork extremely difficult. Researchers can't easily install monitoring equipment or conduct ground studies when the region remains politically volatile and militarily sensitive.

Eesha Tariq, Wikimedia Commons

Eesha Tariq, Wikimedia Commons

The Global Monitoring Gap

Earth has approximately 1,350 potentially active volcanoes. Only about 200 are continuously monitored with ground instruments. The rest, like Taftan, are watched sporadically or not at all. Resources concentrate on volcanoes near major cities. It leaves remote mountains ignored until something unexpected happens.

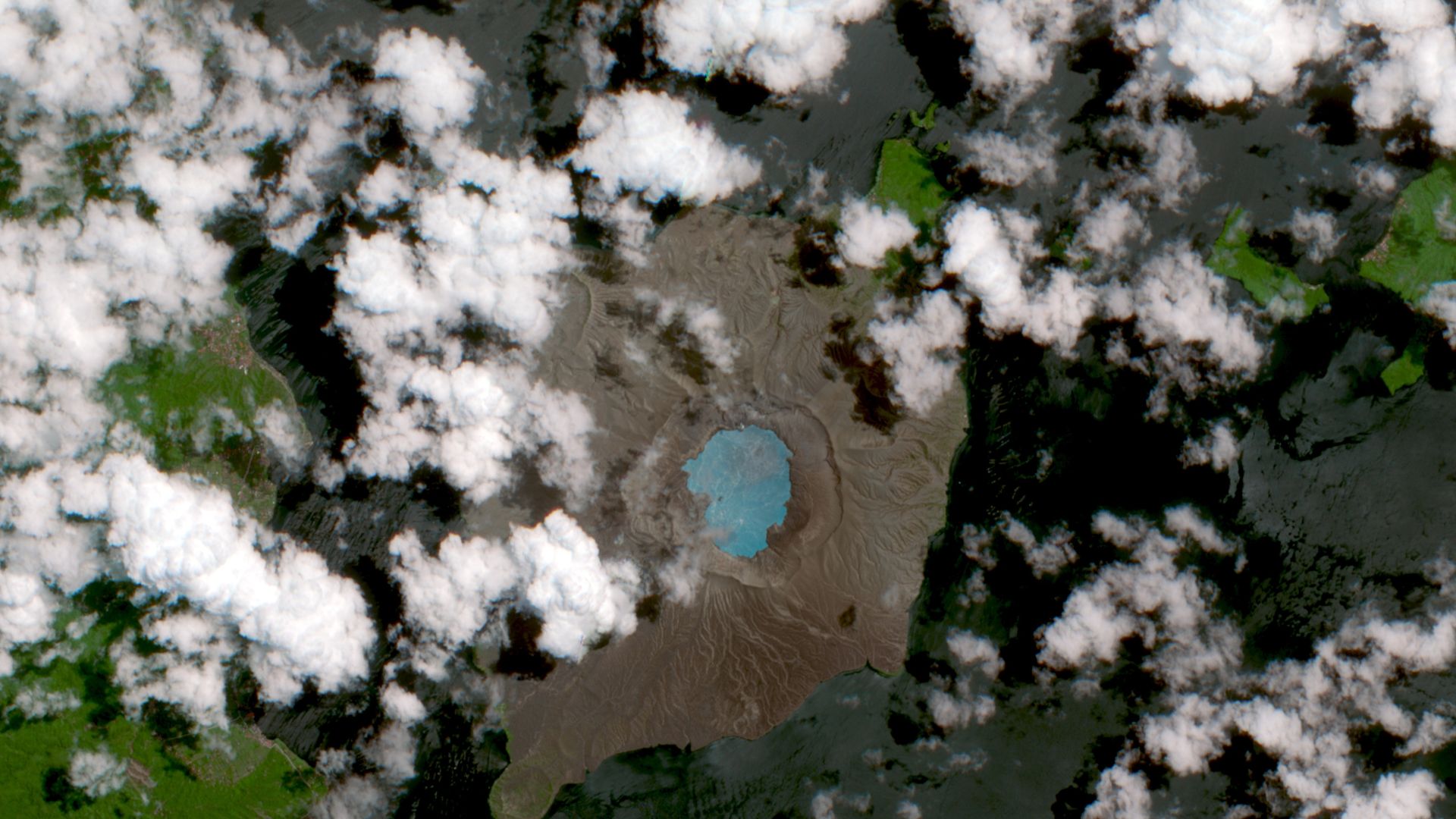

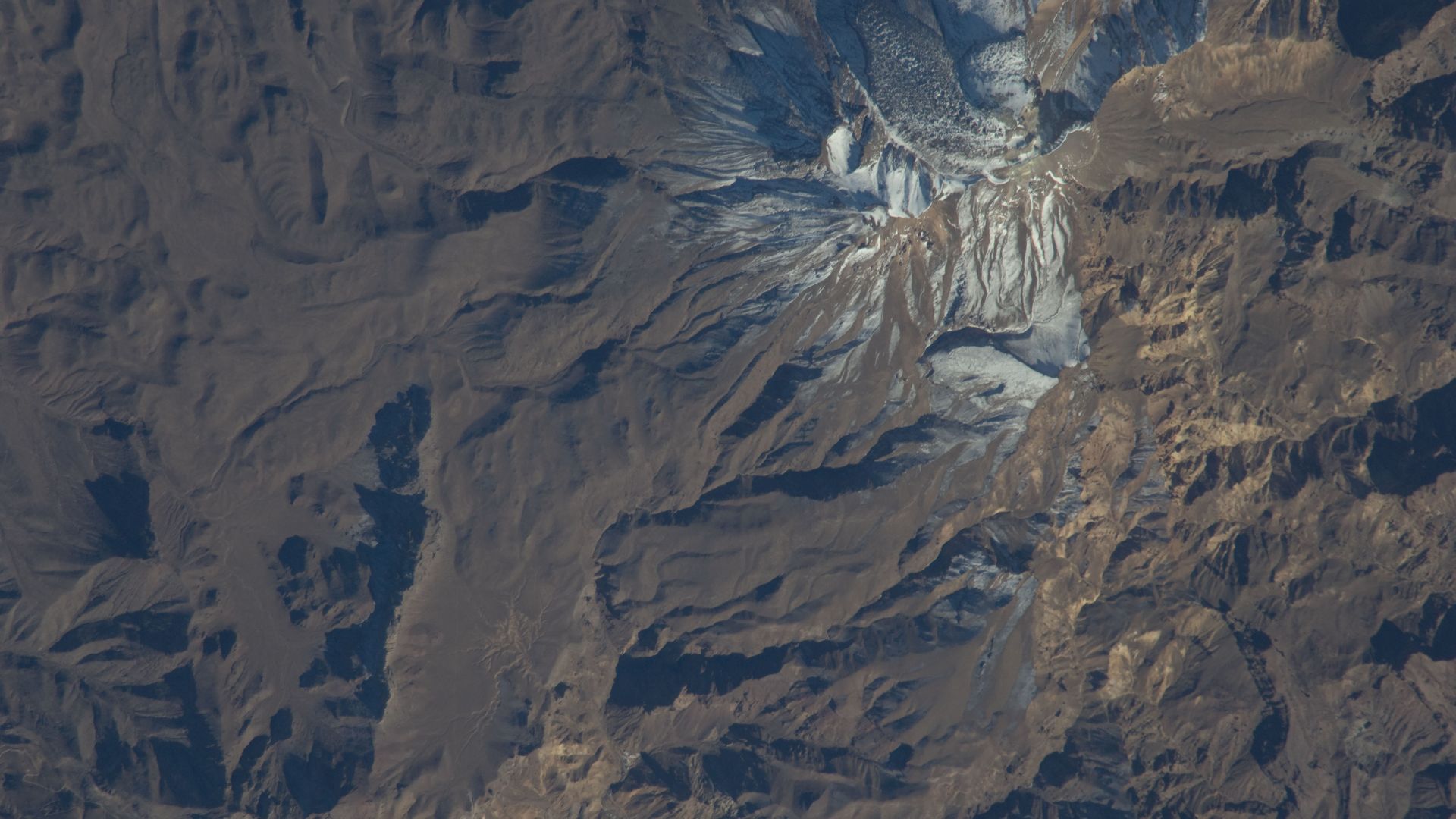

European Union, Copernicus Sentinel-2 Imagery, Wikimedia Commons

European Union, Copernicus Sentinel-2 Imagery, Wikimedia Commons

The Volcano's Ancient History

This volcano last erupted between 700,000 and 710,000 years ago—during a period when early humans were increasingly using controlled fire, as per archaeological records. The volcano evolved through three major stages over millions of years, which built layer upon layer of lava and ash into today's mountain.

Amirhossein Nikroo, Wikimedia Commons

Amirhossein Nikroo, Wikimedia Commons

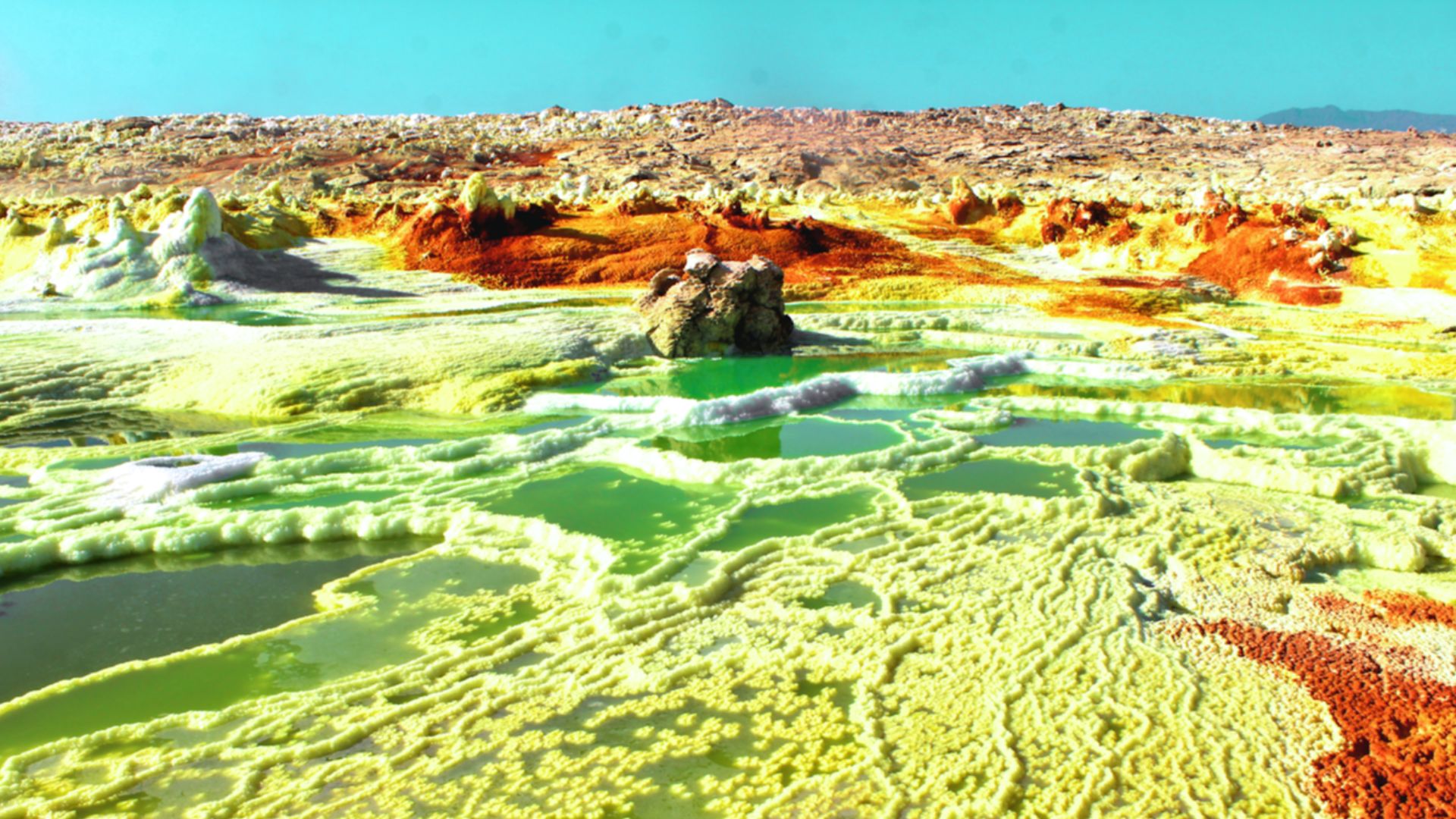

Signs Of Underground Life

Despite its long silence, it never fully died. Fumaroles—volcanic vents—continuously hiss sulfur dioxide gas and steam from cracks near the summit. Hot springs bubble at the volcano's base, and thick yellow sulfur deposits coat the peaks.

Safa.daneshvar, Wikimedia Commons

Safa.daneshvar, Wikimedia Commons

The Scientists Behind The Discovery

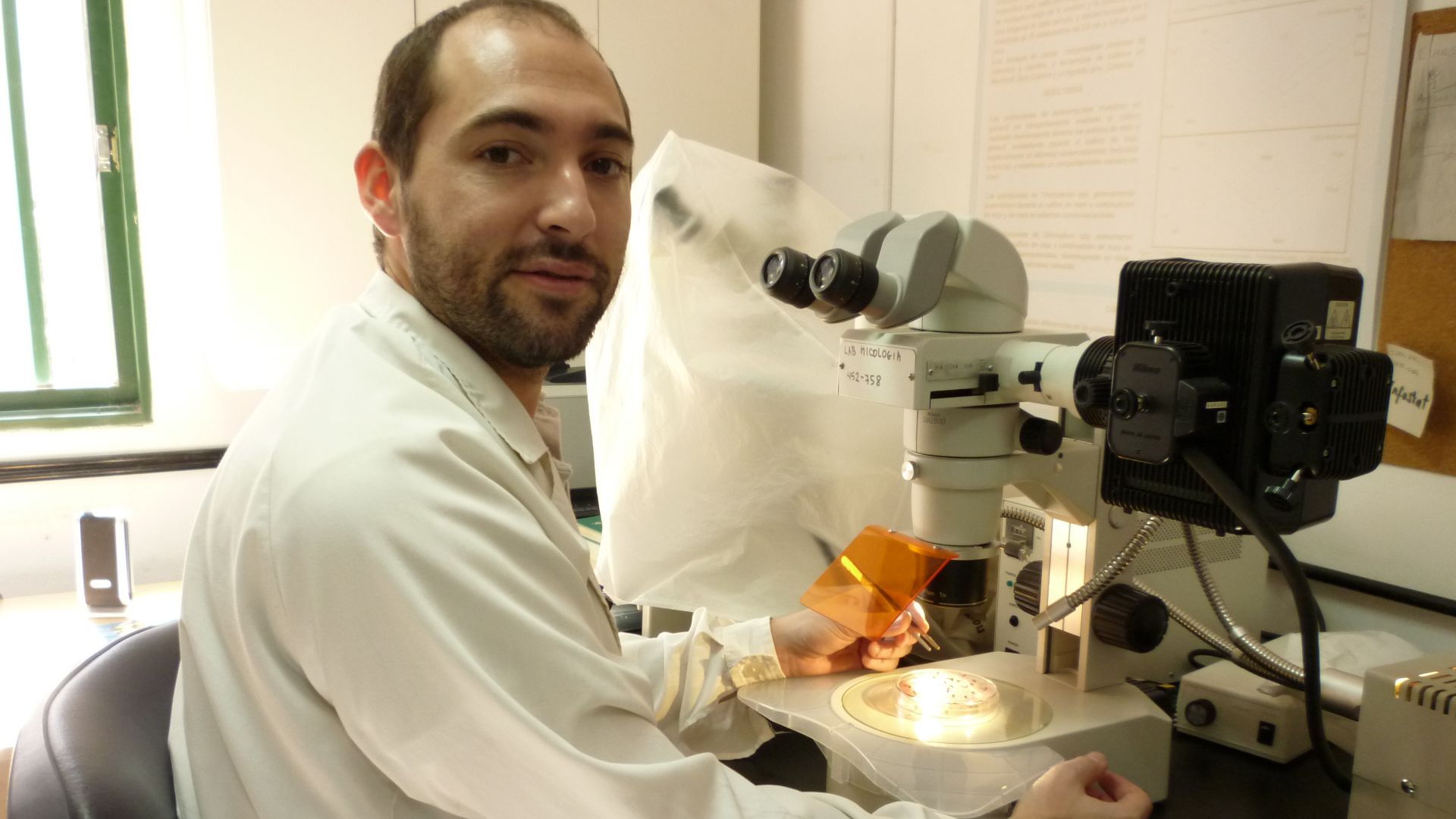

Pablo Gonzalez, a researcher at Spain's Institute of Natural Products and Agrobiology, led the investigation. His PhD student, Mohammadhossein Mohammadnia, played a crucial role in analyzing satellite data. Together, they uncovered what ground-based observers had completely missed for over a year.

Pablo J. Gonzalez, Wikimedia Commons

Pablo J. Gonzalez, Wikimedia Commons

Satellite Eyes Watching Earth

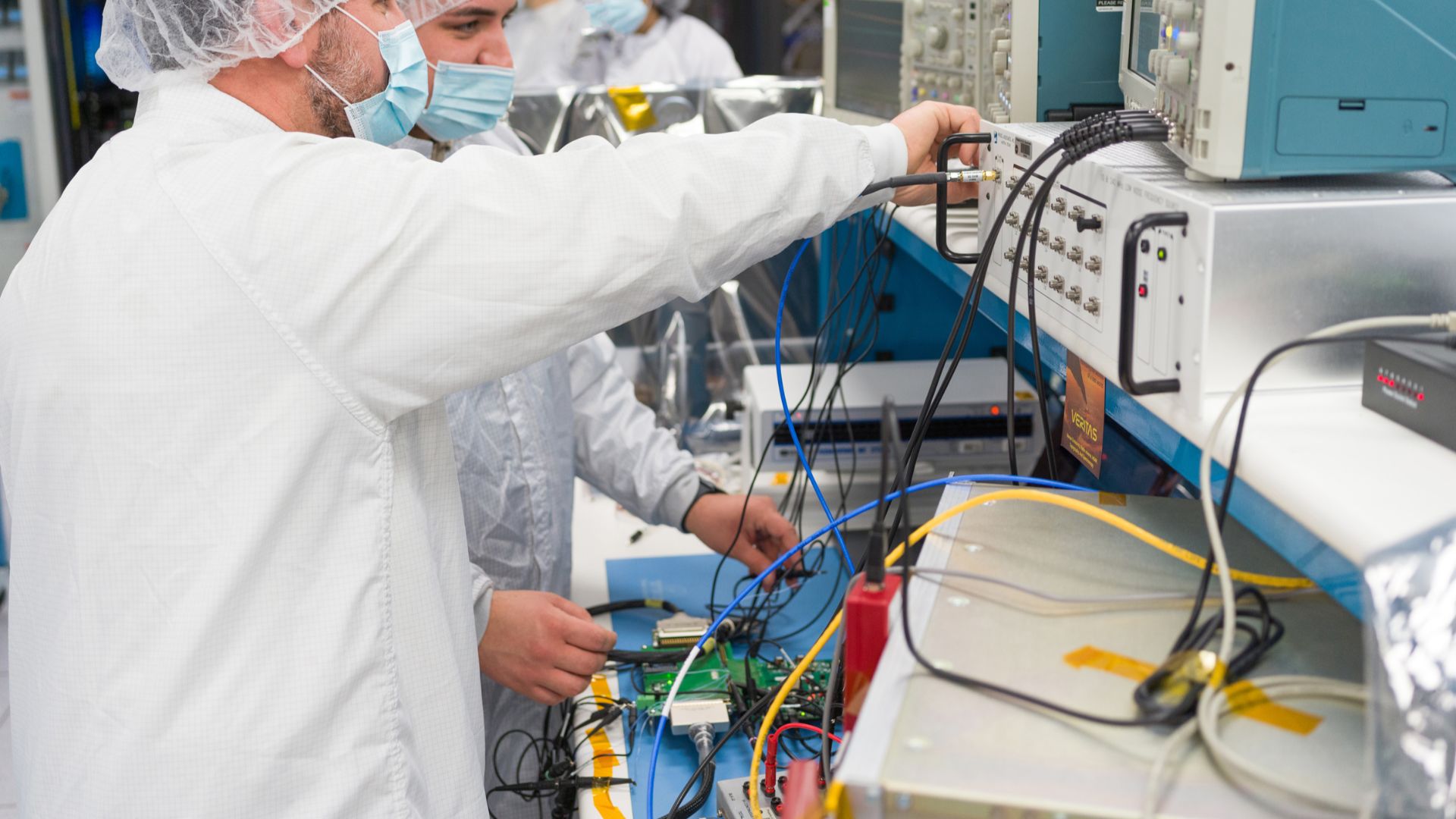

The European Space Agency's Sentinel-1 satellites orbit Earth continuously to scan the surface with powerful radar. These twin satellites were launched in 2014 and pass over the same locations every six days to capture changes invisible to human eyes.

European Space Agency, Wikimedia Commons

European Space Agency, Wikimedia Commons

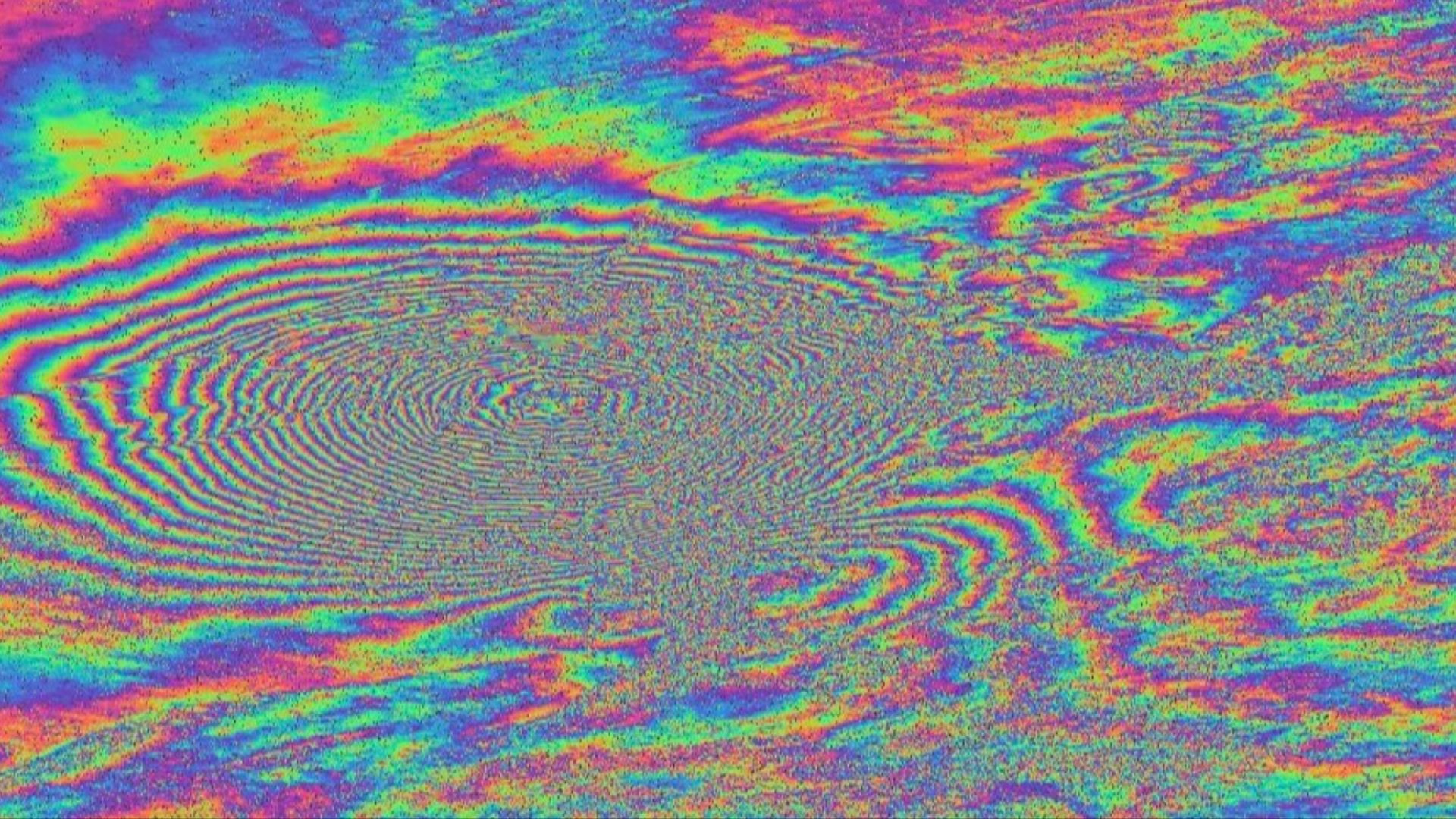

InSAR Technology Explained

Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar may sound complicated, but the idea is simple. Satellites send radar signals toward Earth and track how they bounce back. By comparing images taken over time, scientists can spot ground shifts as small as fractions of an inch—even from space.

NASA/JPL-Caltech, Wikimedia Commons

NASA/JPL-Caltech, Wikimedia Commons

The Common-Mode Filter Breakthrough

Gonzalez's team applied a technique called common-mode filtering directly to the InSAR data. This method identifies atmospheric noise patterns shared across stable reference areas, then removes them from the volcanic signal. It reduced interference significantly. They could detect movements just a fraction of an inch per month.

Roberto Monti, Wikimedia Commons

Roberto Monti, Wikimedia Commons

When The Ground Started Moving

July 2023 marked the beginning. Satellite radar detected the first subtle uplift near Taftan's summit. No one on the ground noticed anything unusual. The mountain looked identical. But from space, the evidence was undeniable: the volcano's surface was slowly rising upward.

Ten Months Of Silent Swelling

Between July 2023 and May 2024, the summit rose about 3.5 inches in total. At its fastest point, the ground lifted at nearly 4.3 inches per year. It marked a noticeable shift in surface elevation over less than 12 months.

Ten Months Of Silent Swelling (Cont.)

Although the movement seems small, it carries major meaning. The volcano had been labeled as dormant for so many years, so any uplift suggests significant changes occurring deep underground, likely involving pressure buildup or magma movement beneath the surface.

Ruling Out False Triggers

The researchers systematically eliminated every possible non-volcanic explanation, such as weather changes, that could have caused this shift. The deformation was "spontaneous" and "triggerless"—it came from volcanic processes alone, not external forces pushing the mountain upward.

National Cancer Institute, Unsplash

National Cancer Institute, Unsplash

The Pressure That Remains

The uplift plateaued but never decreased as per satellite reports. Such persistence tells scientists something critical: the gas causing the swelling hasn't escaped or dissipated yet. But there was a possibility that the team could not deny for the future.

Earth Science and Remote Sensing Unit, Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center, Wikimedia Commons

Earth Science and Remote Sensing Unit, Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center, Wikimedia Commons

Daily Gas Emissions Increase

Scientists measured sulfur dioxide release at approximately 20 tons per day during the uplift period. It represents a significant increase from baseline levels. Sulfur dioxide originates deep underground where volcanic gases separate from magma, then travel upward through cracks to reach the surface.

Safa.daneshvar, Wikimedia Commons

Safa.daneshvar, Wikimedia Commons

The May 2024 Gas Bursts

Computer modeling pinpointed the pressure buildup about 1,600 to 2,070 feet beneath the surface (roughly 490 to 630 meters deep). Several intense gas emission events occurred in May 2024. These were sudden bursts rather than the regular release.

selpa okta prima tysmayer, Pexels

selpa okta prima tysmayer, Pexels

What Locals Were Experiencing

In 2023, Iranian social media users began reporting unusually strong sulfur odors drifting through nearby communities, along with increased fumarole activity on the volcano’s slopes. These early signs hinted that underground gas buildup was intensifying around Taftan.

What Locals Were Experiencing (Cont.)

By 2024, conditions grew more serious. Residents in Khash, about 31 miles away, sought hospital care for breathing irritation, skin reactions, burning eyes, and severe allergies caused by sulfur exposure. It turned a hidden volcanic process into a real public health concern.

Nasrollah koohkan, Wikimedia Commons

Nasrollah koohkan, Wikimedia Commons

How Stratovolcanoes Work

Stratovolcanoes like Taftan are composite structures built from alternating layers of solidified lava flows and volcanic ash. Their magma is thick and viscous, which traps gases inside. When pressure exceeds the rock's strength, these volcanoes produce some of Earth's most violent and explosive eruptions.

Thomas Kraft, Kufstein,, Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Kraft, Kufstein,, Wikimedia Commons

The Magma Chamber Below

Taftan’s magma reservoir lies more than 2 miles beneath the surface—over 3.5 kilometers deep. At this depth, molten rock pools within a chamber inside the Earth’s crust. While current activity doesn’t show magma rising, the chamber’s presence means the volcano remains a long-term threat.

Omran Sepahi, Wikimedia Commons

Omran Sepahi, Wikimedia Commons

Hydrothermal Systems As Alarm Bells

A hydrothermal system is where groundwater meets volcanic heat underground. Water seeps down through cracks, gets superheated by hot rock, mixes with volcanic gases, and then rises back up. Changes in pressure, or gas content within this system, signal what's happening at greater depths.

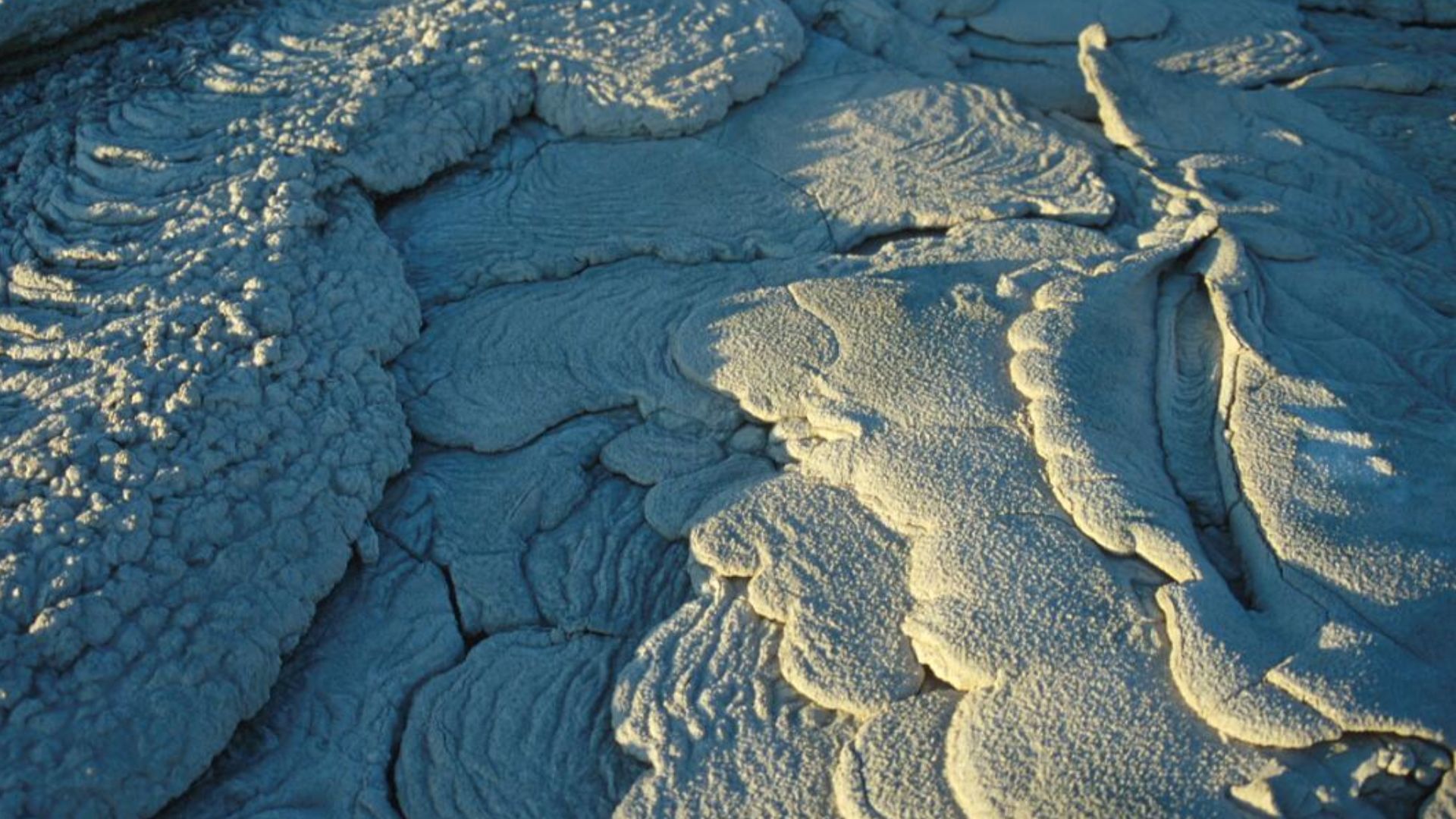

Electra Kotopoulou, Wikimedia Commons

Electra Kotopoulou, Wikimedia Commons

Lessons From Mount Pinatubo

Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines slept for about 500 years before violently erupting in 1991. Scientists discovered magma reactivated the chamber in a matter of months—not centuries. Long dormancy doesn't guarantee slow awakening. Volcanoes can transition from quiet to catastrophic remarkably fast.

NOAA/NGDC, R. Lapointe, U.S. Air Force., Wikimedia Commons

NOAA/NGDC, R. Lapointe, U.S. Air Force., Wikimedia Commons