Secret Affairs. Murderous Rages. Horrific Brutality. More often than not, Tsars of Russia gave the word "tyrant" a new meaning. With every single one of them belonging to the Romanov dynasty, the Tsars ruled Russia for centuries. Some were great, others were terrible—but they were all leading the Empire to its inevitable doom.

Tsar Facts

1. Ivan the Fourth, Actually

Despite truly being one of a kind, Ivan the Terrible was actually the fourth Ivan to rule Russia. His grandfather was the third Ivan, but he managed to acquire the title “Ivan the Great.” We can only fathom what Gramps must have thought of his grandson’s reign.

2. It Was in His Blood

Ivan was the first son of Vasili III, Grand Prince of Russia, and his second wife, Elena Glinskaya. Interestingly, his mother’s family was descended from the Mongolian warlord Mamai, who famously led the Golden Horde—better known as the people who put Russia under the yoke of the Tatars for 200 years.

3. Never Too Young to Start

Ivan became the Grand Prince of Russia at the tender age of three years old. This was because his father, Vasili, contracted blood desease from an abscess and an inflamed leg. We’re hoping that Ivan hadn’t made an ironic wish on his third birthday.

Viktor Vasnetsov, Wikimedia Commons

Viktor Vasnetsov, Wikimedia Commons

4. Mom’s in Charge

Because of the new Grand Prince’s inability to form sentences, his mother took on the role of Regent while Ivan was presumably charged to try and get some kind of childhood out of his life. Among Elena’s actions as Regent was the construction of a defensive wall around Moscow and a peace agreement with Lithuania in 1536. However, Elena’s time was cut short as well, as she passed when her son was eight years old under mysterious circumstances.

5. Blood and Fury

One of Ivan the Terrible’s most notorious actions was his orchestration of the Liquidation of Novgorod. Convinced that the leading citizens of the city were conspiring with his enemies inside and outside of Russia, Ivan launched the full might of his power on the city and its population. His men burned fields, looted all the city's buildings, and either liquidated the city's people or drove them out of the city in mid-winter to pass of exposure and starvation.

Sources cannot agree on the number of deaths, listing them as low as 2,500 and as high as 60,000. Regardless of the number, his role in this event more than earned Ivan his historic title.

6. Let’s Try This New Title Out

In 1547, at the age of 16, Ivan IV was crowned at the Cathedral of the Dormition. However, he wasn’t crowned a Prince, like the rulers of Russia had previously been. Instead, Ivan was crowned "Tsar of all the Russias." This made Ivan the Terrible the very first Tsar in Russian history.

7. You Win the Contest!

On the way to becoming ruler of Russia, authorities planned a massive ball for him to select a wife—the future Tsarina. Hundreds of potential brides were hurried into the Kremlin for their chance. Ultimately, Ivan went with Anastasia Romanovna, who became the first Tsarina of Russia—which wasn't necessarily a desirable honor, given how things would turn out.

8. Fruitful Family

After they got married in 1547, Anastasia and Ivan got busy producing children, as they were expected to do. The couple would have six children: Anna, Maria, Dmitry, Ivan, Eudoxia, and Feodor.

9. Terrible Tragedies

Sadly, the survival rate for Ivan’s children turned out to be shockingly low. Neither Anna nor Maria survived past the age of one. Meanwhile, Eudoxia didn’t live to be two years old. But everything was okay for the others, right? Right?

10. Carry Me Down to the River

In 1553, Ivan took his family on a holy pilgrimage to the Kirillo-Belozersky Monastery. The route took them down the Sora River, which tragically led to their boat being overturned. While Ivan and Anastasia escaped drowning, their eldest son—and at the time, only surviving child—Dmitry was dropped by his wet-nurse in the middle of all the chaos.

We have no idea what happened to said wet-nurse, but part of us doesn’t really want to know what happens to a woman who fails to save the son of a ruler named Ivan the Terrible.

11. Bad Omen

Just a few months after Ivan IV became Tsar, the Great Fire of 1547 engulfed the city of Moscow. The fact that many of Moscow’s buildings were made out of wood only helped the fire spread faster. In total, more than 80,000 people were made homeless by the fire, while nearly 4,000 lost their lives.

12. Blame the Tsar…’s Grandma!

The populace blamed Ivan’s maternal relatives, the Glinski family, for the Great Fire. In particular, they accused Ivan’s grandmother of using sorcery to start the fire in the first place. Strangely, the uprising that caused several Glinski family members to either go into hiding or be publicly liquidated only increased Ivan's power.

For what it’s worth, he stepped in and protected his grandmother from the mob that wanted her gone.

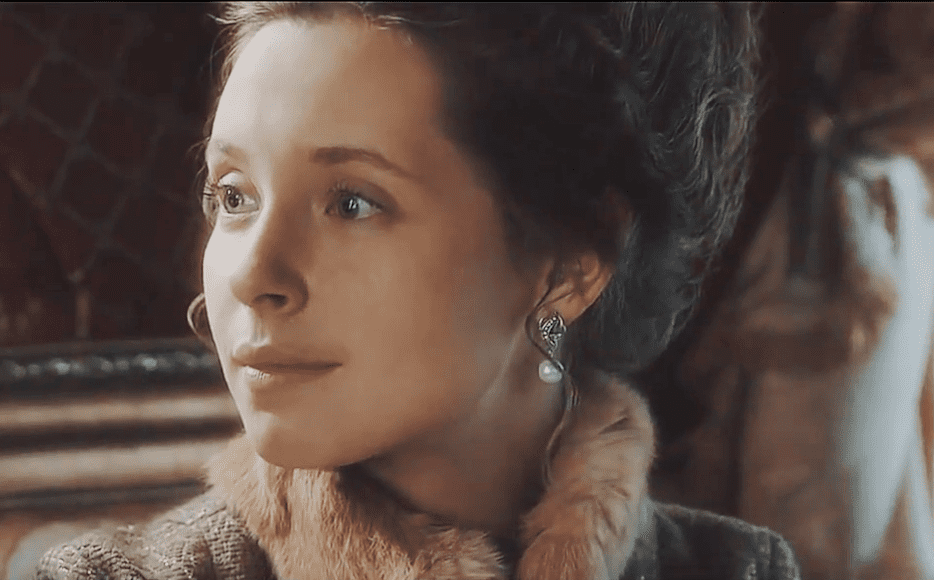

Ivan the Terrible, Part II (1958), Mosfilm

Ivan the Terrible, Part II (1958), Mosfilm

13. Russian, Not a Roman

Since Ivan wanted to impress on his subjects that he was the absolute ruler of Russia, he picked his new title wisely. "Tsar" is a Russian translation from the Latin word "Caesar," and we don’t need to tell you what that means, do we?

Ivan the Terrible, Part I (1944), Mosfilm

Ivan the Terrible, Part I (1944), Mosfilm

14. The Last Straw

Ivan had many reasons to hate the Russian aristocracy, also known as the boyars. However, things were pushed to their limit when his first wife, Anastasia, who many had said had provided a sobering, wise approach to Ivan’s rule, fell ill and passed in 1560. This tragedy allegedly drove Ivan into a state of emotional collapse, especially since he was convinced that she had been poisoned by the boyars.

Several of them were tortured to demise on his orders.

Ivan the Terrible, Part I (1944), Mosfilm

Ivan the Terrible, Part I (1944), Mosfilm

15. I Quit!

The 1560s brought on a serious change in Ivan’s behavior. In December 1564, he shocked Russia by leaving Moscow and announcing his abdication due to a conspiracy that threatened his life. This put the boyars in a terrifying position since they were afraid of a peasant uprising (no idea why Russian nobles would ever fear such a thing). They ultimately begged Ivan to come back and be their Tsar.

Ivan agreed, on the condition that he become an absolute monarch with the power to basically do whatever he wanted. Things must have been pretty bleak, because his terms were accepted.

Ivan the Terrible, Part I (1944), Mosfilm

Ivan the Terrible, Part I (1944), Mosfilm

16. Rebound Remorse

A year after his first wife passed, Ivan married Maria Temryukovna, who was only seventeen and perceived as illiterate. Ivan, however, was stricken by Maria's great beauty. The marriage was one of his least successful. Not only did their only child pass young—continuing a grisly trend when it came to Ivan’s offspring—but Maria was unpopular and unable to adjust to life in Moscow.

Upon her passing in 1568, rumors spread that Ivan had poisoned her, though it’s recorded that he went on a witch hunt to find out the true cause of her passing , so the truth will never be known.

17. Hero of the People???

Bizarrely, flying in the face of all that history has tried to say about him, Ivan the Terrible was wildly popular among the commoners in Russia. Because he curbed the powers of the nobility and aristocracy, he was hailed as a man who stood up for the rights of the lower class.

Ivan the Terrible, Part I (1944), Mosfilm

Ivan the Terrible, Part I (1944), Mosfilm

18. The Thief and the Terrible

Several folktales from his era depict Tsar Ivan in a positive, even light-hearted demeanor. In one story, the Tsar goes amongst the people in disguise. He befriends a thief, who invites the stranger to join him in his robberies. When Ivan suggests they rob the royal treasury, the thief reacts with outrage, saying he would never take from the Tsar. He prefers to take from the boyars since they did nothing to earn their great wealth and simply inherited it.

Ivan is so impressed by the thief’s (slightly lopsided) ethics, that he hired the man as one of his counselors, presumably while wacky music plays as the two men start laughing and patting each other’s backs.

Ivan the Terrible, Part I (1944), Mosfilm

Ivan the Terrible, Part I (1944), Mosfilm

19. "Secret Authorities" Would Have Been Too Obvious

With his newfound absolute power, Ivan set up the policy known as Oprichnina. What it entailed basically amounted to Ivan taking territory held by Russian aristocrats, reassigning to his political force known as the oprichniki, and giving the Tsar control over huge swathes of Russian land. The oprichniki, meanwhile, exploited their position as they either drove off or liquidate the aristocrats.

20. General Tsar, Sir!

Ivan was busy with army campaigns. As early as 1552, Ivan led an army of 150,000 to the great city of Kazan, occupied by the descendants of the Golden Horde. Ivan’s army besieged the city for over a month before it finally fell. Up to 100,000 Russian slaves were liberated, while the Tartar population was slaughtered.

Ivan led his forces to annex the Astrakhan Khanate, which also destroyed the biggest slave market on the Volga River.

21. Classic Overbearing Mother-in-Law

Marfa Sobakina was the winner of twelve finalists to become the Tsar’s third wife. However, it was a case of the winner being the loser. Marfa’s mother allegedly gave her a potion to make her more fertile—given Ivan’s track record, we can’t really blame her. Unfortunately, the potion ended up giving poison to her. She was so ill that she could barely stand on the day of her wedding, and she passed a few days later.

In the midst of such a disastrous honeymoon, Ivan became even more paranoid, even ordering his former brother-in-law to demise by impalement—eat your heart out, Vlad.

Hans Weigel der Ältere, Wikimedia Commons

Hans Weigel der Ältere, Wikimedia Commons

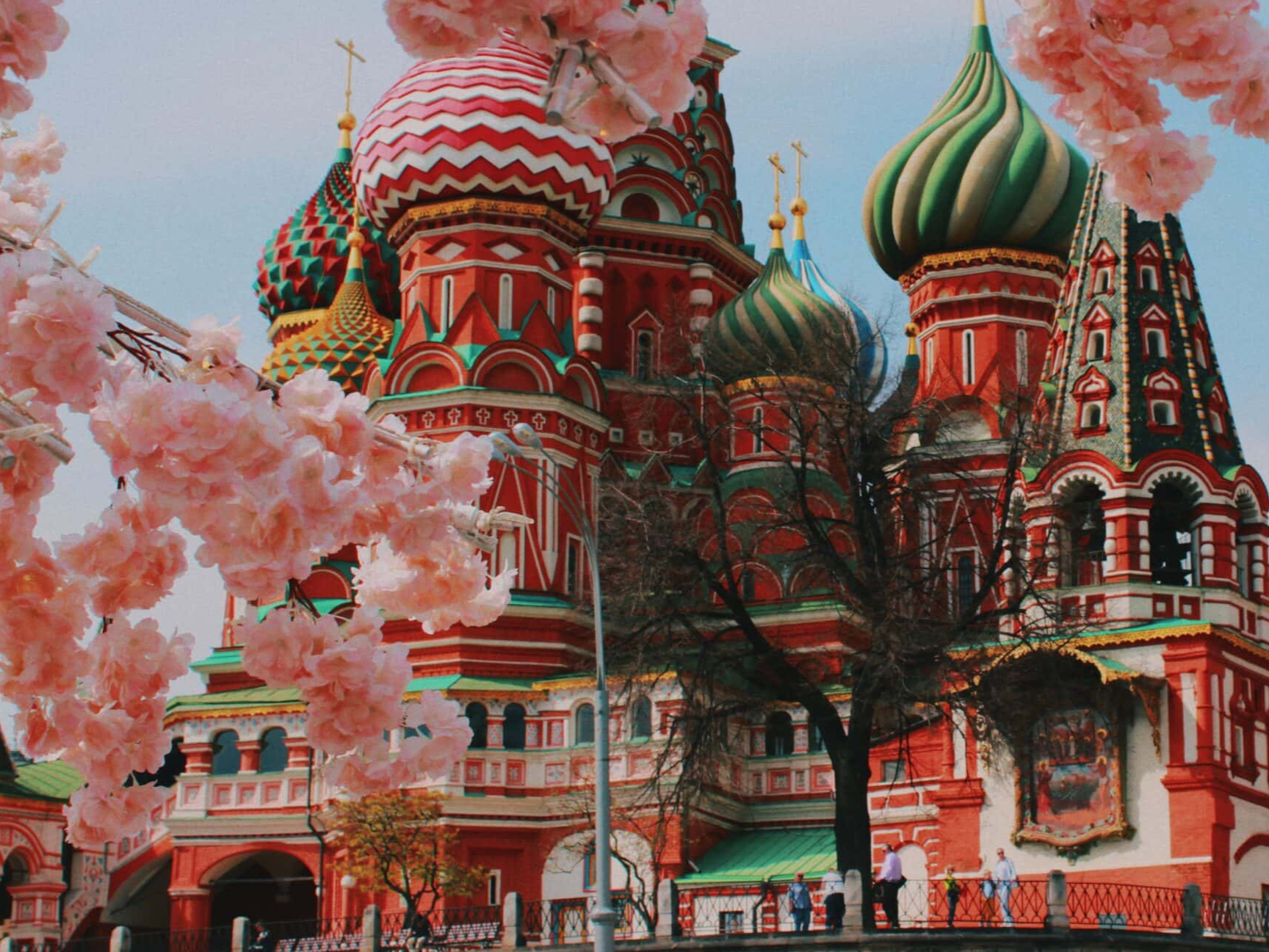

22. A Modest, Economical Structure

If there’s one thing that conquerors like to do after a successful army campaign, it’s immortalizing their accomplishments with a monument. In Ivan’s case, conquering Kazan from the Khanates demanded a special kind of structure. On his orders, the architect known as Postnik Yakovlev designed St. Basil’s Cathedral in Moscow. Say what you will about Ivan, he knew who to pick to make a nice-looking cathedral.

23. I Would Have Accepted Cash!

There is a popular legend that when Ivan beheld the beautiful cathedral and he repaid Yakovlev by blinding him so that he would never make anything so beautiful again. While it’s tempting to treat this is as fact, many historians dispute this story because Yakovlev would go on to design several buildings after his work on St. Basil’s Cathedral. Then again, maybe Yakovlev was just that talented?

24. Two Annas For the Church

Unfortunately for Ivan, the Russian Orthodox Church frowned on more than one remarriage. Ivan countered that the third marriage had never been consummated, so it didn’t count. He married Anna Koltovskaya in 1572, but two years later, her inability to produce children caused Ivan to send her to live the rest of her life in a convent.

This was ultimately good for her, since she was only one of two of Ivan’s wives to outlive him. Ivan’s fifth wife, Anna Vasilchikova, was less fortunate, dying in 1577 despite also being sent to a monastery to live as a nun.

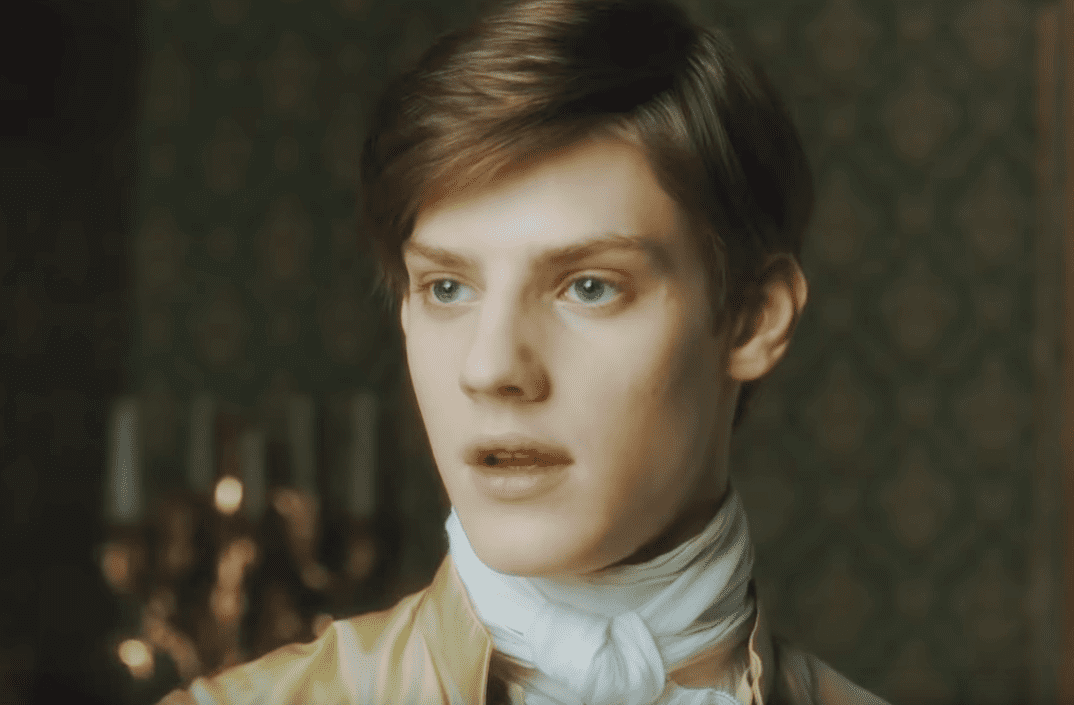

25. The Good Son

Ivan’s second son, also named Ivan, was a rare bright spot in his father’s life. He is alleged to have saved his father’s life when he ended a Livonian prisoner who raised a sword against the Tsar.

26. Talk About an Interfering Parent

After the Livonian conflict, however, things deteriorated between the two Ivans. What didn’t help was Ivan Sr.’s obsession with his son’s progeny. Ivan Jr. was married to two different women who Ivan Sr. eventually sent to become nuns instead. By the time Ivan Jr. was 27, he had married a third time, and the third time was the charm because she soon became pregnant.

Grigory Sedov, Wikimedia Commons

Grigory Sedov, Wikimedia Commons

27. The Sparks Before the Fire

For all his popularity with the common people, not all that Ivan did was in their favor. It was he who installed the first laws restricting peasants’ movements in Russia. This would provide the beginnings of a slippery slope that led to serfdom in Russia, which in turn would inspire the serfs to revolt against Ivan’s descendants.

28. My Son, My Son, What Have I Done?

Of course, when things finally seemed to go right with Ivan Jr. and his soon-to-be grandchild, nobody counted on Ivan the Terrible living up to his name. On November 15, 1581, Ivan IV witnessed his pregnant daughter-in-law wearing clothes that he determined to be less-than-appropriate. He proceeded to physically assault her until Ivan Jr. heard her screams and accosted his father.

Things had already gone way too far, but then Ivan Sr. struck his son’s temple with his scepter in a fit of rage. The head wound proved fatal, much to Ivan Sr.’s horror. This, coupled with his daughter-in-law’s miscarriage due to the attack, immortalized Ivan’s image as a mentally unstable tyrant who would end his own children.

Ivan the Terrible, Part II (1958), Mosfilm

Ivan the Terrible, Part II (1958), Mosfilm

29. Thus the Terrible Passed

In March 1584, Ivan the Terrible was quietly playing chess with a statesman in his home when he suddenly collapsed and became bedridden. Even today, it’s not fully known what caused him to pass. An old theory posited that he was poisoned, while many modern-day historians allege that it was a stroke.

30. Unsuitable Successor

After most of Ivan’s children had either passed in infancy or had been ended by Ivan himself, his son Feodor became Tsar of Russia. However, while Feodor was beloved for his good nature and his religious piety, he was alleged to have suffered from a learning disability. Regardless, this new Tsar must have given everyone a severe case of whiplash in the aftermath of his terrifying father.

31. The Empire Nearly Perished With Him

After Ivan’s passing, his empire nearly collapsed due to the decisions that Ivan had made when he was alive. His lack of economic skill, coupled with the many wars that the Russians had fought under his rule, meant that the economy was in a very bad state. This led to his own dynasty, the Ruriks, losing power after the passing of Ivan’s son, Feodor, in 1598.

32. Ending Pain

One theory for Ivan’s uncontrollable mood swings and paranoia was the mercury that he began to take as a painkiller. The side effects of mercury would justify his unpredictable emotions.

33. CSI Moscow

The end of Ivan's mother Elena in 1538 has generally been accepted as being due to giving poison, which was confirmed when her remains were exhumed and examined in more recent years. At the time, her son’s governess was taken into custody for it, but several historians have since argued that it may likely have been one of the rival boyar families—Russian nobles that were second only to the ruling princes. With Elena out of the picture, the boyar nobility competed for power.

Shakko, CC BY-SA 3.0 , Wikimedia Commons

Shakko, CC BY-SA 3.0 , Wikimedia Commons

34. Maintaining Perspective

Paul I of Russia was often referred to as “the Mad Tsar.” While it’s certainly debatable just how mad he really was (we’ll get to all that later), we must remember that Paul’s enemies wanted to slander his name and legacy. However, when you look at the life that he lived, it's hard to say the shoe doesn't fit...

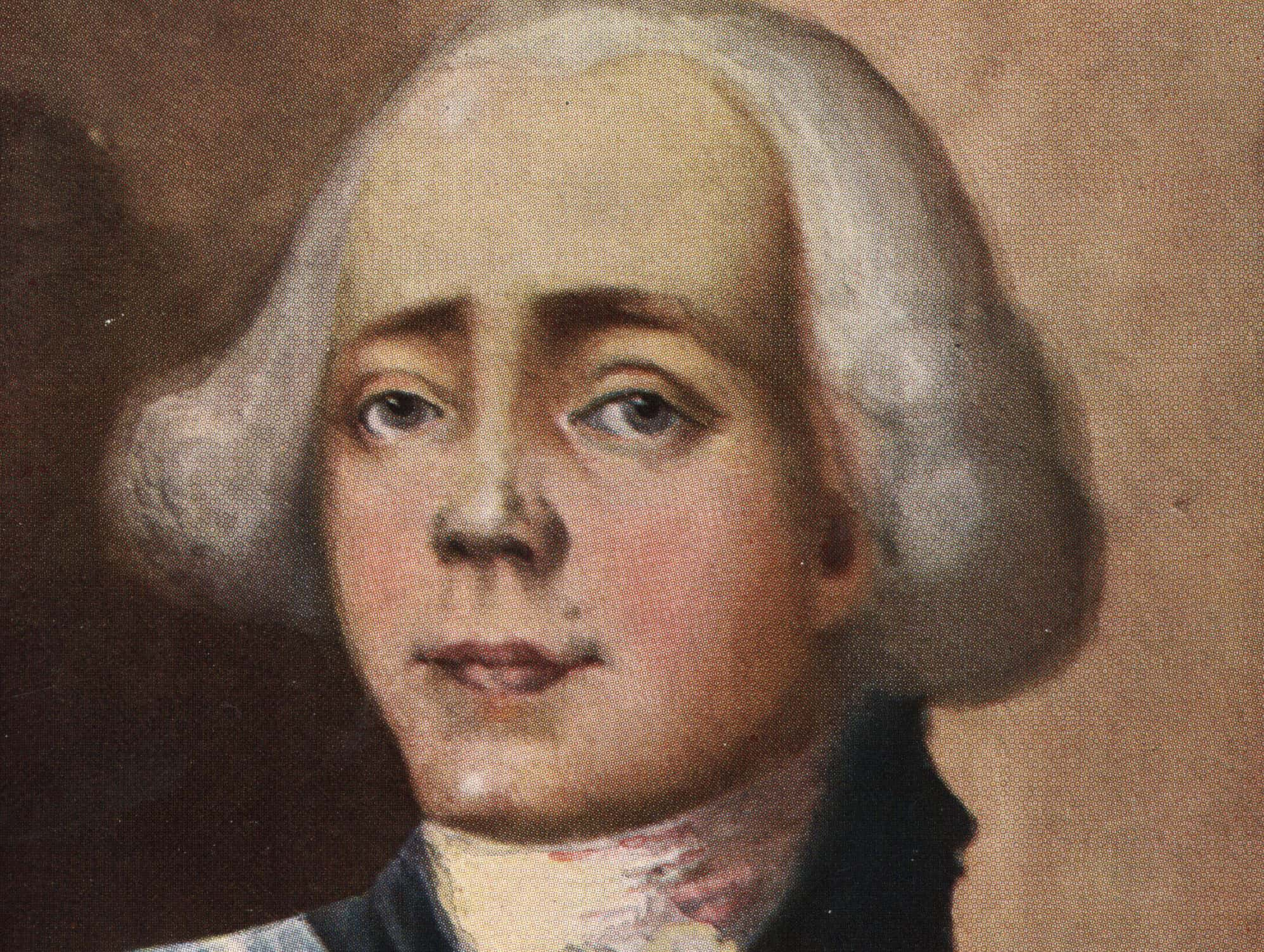

35. Bragging About the Bloodline

Paul was a member of the House of Romanov, an ancient family that ruled Russia from the 17th century up until the early 20th century. However, Paul was descended from the Romanovs through his mother’s line rather than his father’s, so his official house was listed as “Holstein-Gottorp-Romanov.” The name "Romanov" was included in order to emphasize Paul’s descent from Peter the Great.

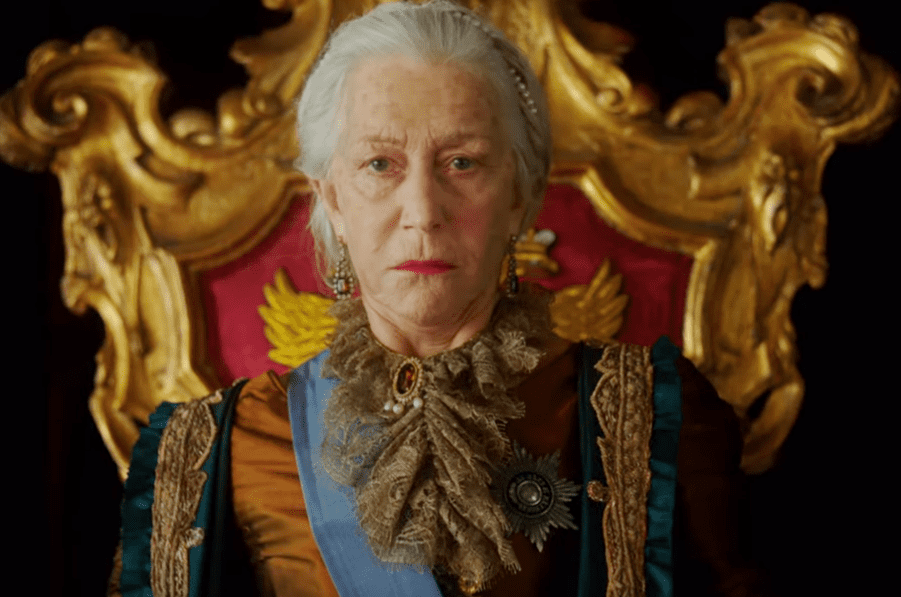

36. A Russian Version of Prince Charles

Paul spent most of his life waiting for his turn to sit on the Russian throne. His mother, Catherine the Great, was a long-lived ruler, and Paul was already in his forties when he was crowned emperor. Unlike his mother, Paul had a very short reign, ruling for around four years before his own demsie.

37. Three’s a Crowd

Like so many other monarchs in European history, Paul wasn’t without his royal mistresses. In the late 1770s, Paul began an affair with Yekaterina Nelidova, a lady-in-waiting to both his first and second wives. In 1798, he replaced Nelidova with Anna Lopukhina, much to his wife Sophia’s fury.

38. Call it a Promotion

Paul was eight years old when Empress Elizabeth passed in 1762. This left Paul’s father to be crowned as Tsar Peter III of Russia. Paul was immediately made the new crown prince, and his father’s heir.

39. Overly Nurtured

It’s often been stated that Empress Elizabeth proved a very negative influence on Paul as he was growing up. Spending so much time away from his parents and being emotionally smothered by his great-aunt have been used by historians as possible explanations for his many eccentricities.

40. Mom, Dad, Please Stop Fighting…

In a shocking turn of events, Paul’s father only reigned as Tsar Peter III for less than a year. The unpopular figure fell victim to a coup that was organized by his own wife, and Paul’s mother, Catherine. Peter III became a prisoner of his own subjects, and he abdicated on their orders. Catherine became Catherine II of Russia. Paul, meanwhile, continued to be the crown prince, since it was still his parent on the Russian throne.

41. Custody Switch, Part 1

Shortly after Paul’s birth, Empress Elizabeth snatched him from his mother’s custody. It’s not fully known why this was the case, but several theories exist. One idea is that Elizabeth disliked Catherine and saw her only as someone who could produce an heir to the Russian throne. When Paul was born, Elizabeth swooped in and took charge of the boy, separating him from Catherine except for brief visits.

42. Custody Switch, Part 2

By contrast, some historians claim that Paul was taken away from his mother for his own safety. Allegedly, Catherine despised her own son and needed to be restrained from ending him! On another occasion, Catherine celebrated her birthday by gifting one of her favorite courtiers with 50,000 rubles, while Paul was gifted with a watch.

43. Matchmaker, Part 1

When Paul turned 18, he was allegedly eager to claim the throne for his own, as he was confident that as the male heir to his own father and mother, he would be a better ruler than his mother on the grounds of gender alone. Catherine, however, wasn’t ready to step down from being the Empress, so she found a way to distract Paul by finding a bride for him.

44. Matchmaker, Part 2

In order to find a suitable match for her son, Catherine contacted the Prussian Crown Prince Frederick II (better known as Frederick the Great). The woman they picked for Paul was Frederick’s sister-in-law, Princess Wilhelmina of Hesse-Darmstad. When she married Paul in 1773, Wilhelmina took the more Russian-sounding name Natalia Alexeievna.

45. Playing with My Toys

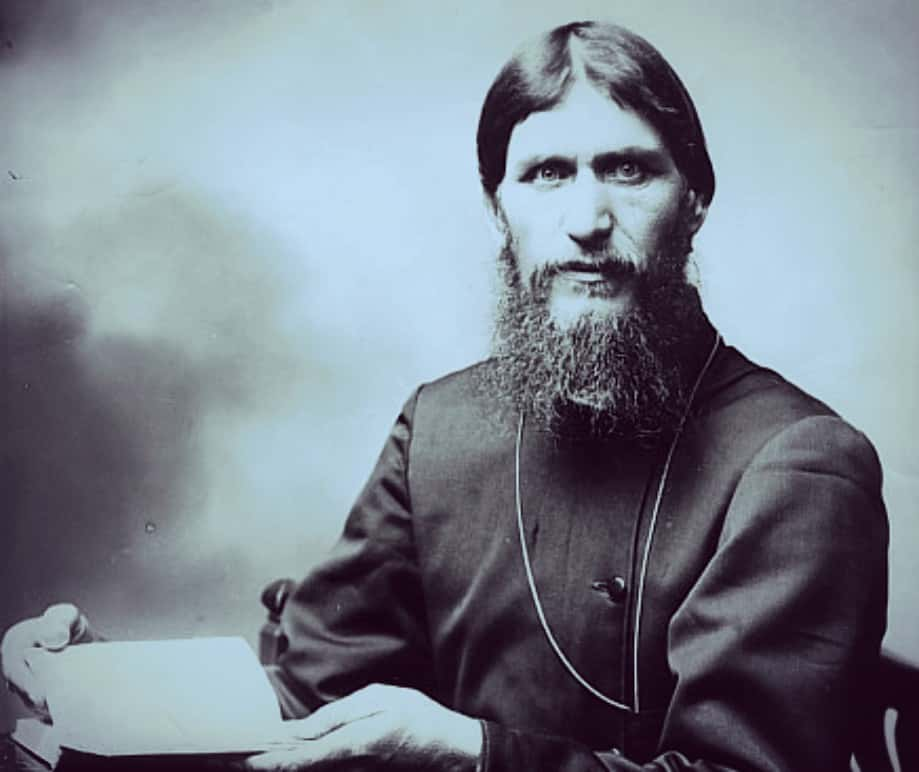

Throughout most of his mother’s reign as Empress of Russia, Paul was far removed from the royal court, and even the capital itself. Throughout her reign, Catherine actively blocked him from becoming involved in politics and governmental administration. Following Paul’s marriage, he was given an estate at Gatchina, just outside of Saint Petersburg. Robbed of any responsibilities, Paul became obsessed with drilling and training the few army units under his command.

It was an obsession that he held for the rest of his life.

46. Domestic Quarrels

Army reform became the stick which Paul used to beat at his mother, even when she was still alive and ruling supreme. At one point during her reign, Paul published a dissertation titled Reflections. In it, Paul criticized an expansionist army policy which his mother had supported and argued that a defensive stance was far more effective. Catherine saw this treatise as an attack upon her, and the Russian nobility was smart enough to avoid supporting Paul against her.

47. Not Exactly a Battle Scar…

Paul’s face was often described as being pug-nosed in appearance. It was also written that his features appeared that way because of a contraction of typhus which he suffered in 1771 in his late teens.

48. Imagine if Joffrey Grew Up

Paul spent much of his adult years viewing Catherine as a rival rather than as his mother. Neither one liked the idea of giving up power to the other, and Catherine didn’t want to give her ambitious son a single inch. Even the suggestion that they become co-rulers was dismissed.

49. Over Too Soon

Reportedly, Paul was very quick to fall in love with his first wife, Wilhelmina, even turning a deaf ear to rumors that she was cheating on him. Whether that rumor was true or not will likely never be known, but what’s known for sure is that Paul was devastated when Wilhelmina passed during childbirth in 1776, just three years into their marriage.

50. Time for Round Two

Despite Paul’s grief for the loss of his first wife, Catherine didn’t wait six months before she found another wife for her son. Like Wilhelmina had been, Paul’s second wife was a German princess. While she was born with the name Sophia Dorothea, she also took a more Russian name when she converted to the Orthodox Church. From then on, she was known in Russia as Maria Feodorovna. She remained married to Paul until his passing.

51. You’re Not Going to Stop Me!

Back in 1722, Peter the Great had passed a decree which stated that Russian emperors could pass over the heirs of their body and pick any new heirs that they saw fit. Catherine reportedly planned to use this decree to deprive her son, Paul, of the Russian throne and name Paul’s son, Alexander, as her heir instead!

If that was the case, she was unsuccessful. Paul ascended the throne upon her passing. He even repealed Peter’s 1722 decree, enforcing the Pauline Laws, which stated that the Russian throne always went to the closest male heir in the royal family.

52. Royal Progeny

Paul’s second marriage resulted in no fewer than six daughters and four sons. Two of Paul’s sons, Alexander and Nicholas, ruled as Tsars of Russia, while one of his daughters, Anna Pavlovna, became a queen in her own right when she married King Willem II of the Netherlands.

53. Nothing but Trouble

Despite Paul’s love for the army , the army didn’t love him back. This was because of Paul’s ideal army wasn’t the Russian army, but rather the Prussian army. Known for their rigorous discipline and drilling ability, Paul tried to impart that in his own men, much to their frustration. Additionally, Paul threw out the comfortable and cheap army uniforms which Catherine had introduced into the army and replaced them with elaborate Prussian-style coats which were difficult to maintain and highly impractical during active duty.

54. Meet the New Boss!

As you can imagine, Paul was obsessed with having complete obedience from his subjects when he finally became the Tsar. Although Catherine had granted several freedoms and rights to the nobility and other Russian classes during her reign, Paul’s policy was a complete reversal. He made it clear that he felt the nobles should only “serve the monarch and the state.”

This led to a lot of ill feelings towards the new Tsar.

55. Welcome Home!

Any enemy of Catherine’s was a friend of Paul’s. When he succeeded his mother to the throne, Paul famously allowed Alexander Radishchev to return to Russia from exile. Radishchev was an author who had frequently criticized Catherine during her reign. We can imagine that Paul was his biggest fan!

56. Will Someone Buy a Baby Monitor?!

Although Empress Elizabeth took Paul into her custody when he was an infant, and even if the rumors about Catherine hating him were true, Paul suffered from neglect with Elizabeth as his caretaker. In a rather infamous anecdote, the infant Paul once “fell out of his crib and slept the night away unnoticed on the floor."

57. Bad Way to Go

For the last few months of Paul’s life, a conspiracy was planned amongst several of his nobles, who were fed up with his rule. After several delays, the plot moved forward in 1801 on the 23rd of March (or the 11th of March, depending on which calendar we’re talking about). That night, the nobles burst into Paul’s bedchambers.

Most of them were inebriated , and when Paul resisted their attempts to make him abdicate, they mobbed him. Paul succumbed to injuries sustained from strangulation, trampling, and a sword thrust. He was 46 years old.

58. Hup Two Three!

Paul’s obsession with complete army discipline and order was honestly more of a paranoia than anything. He ordered his men whipped if they made a mistake during their army parades and forced them to march in any weather conditions. On one occasion, Paul was so infuriated by a group's failure to stay ordered during a maneuver, that he ordered them to march all the way to Siberia!

Luckily for the army men, he changed his mind after they were ten miles into the long journey.

59. Good Thing We Called It Off

Paul’s abrupt removal from power (and life) put an end to his most bizarre army campaign before it really began. In 1801, Paul plotted with Napoleon to attack the British, but since the island was too dangerous to invade, Paul decided to attack her colony in India. An army of 20,000 Cossacks were sent south to invade India, but the campaign was called off when they heard about what had happened to Paul.

It was probably for the best, because in true Paul style, he hadn’t given his army a proper map of India before they left!

60. How’s That, Mom?!

Paul had nothing but contempt for his mother’s rule, insisting that her “petticoat reign” had resulted in disorder and degeneration, especially within the army . In an act of spite towards his mother’s legacy, Paul seized a palace which Catherine had bestowed on one of her favorites and gave it to a cavalry group so they could use it as a barracks.

61. My Own Inner Circle

In an ironic turn of events, one of the men who liquidated Paul was the nephew of Nikita Ivanovich Panin, Paul’s former governor. On a far more chilling note, Paul’s son, Alexander, allegedly knew about the plot against his father and gave it his blessing! He didn’t even punish his father’s killers, and even pretended that his father had passed of apoplexy.

Paul really didn’t get anything but grief from his family!

62. Someone Call Maury

For his entire life, Paul had to deal with rumors that he wasn’t actually the legitimate son of Peter III. If you’re wondering who would dare to spread such treasonous subject matter, look no further than his own mother, Catherine! Catherine and Peter’s marriage was deeply dysfunctional, and Paul had only been born after ten years of childlessness.

This helped sell the idea that Paul might have been fathered by one of Catherine’s lovers instead of Peter.

63. New Money

From "Mad" to "Great, Paul's great-grandfather Peter was just only two generations removed from the founding of the Romanov Dynasty. His grandfather was Michael I of Russia, the first Tsar from the House of Romanov. Hard to imagine an Imperial Russia without those notorious Romanovs, but when Peter was born, the family were relative newbies on the highborn scene.

Johann Heinrich Wedekind, Wikimedia Commons

Johann Heinrich Wedekind, Wikimedia Commons

64. Cry Uncle

Peter’s father passed when he was only four years old. On 29 January 1676, it was Peter’s uncle, Feodor III, who took the throne. Unfortunately, his reign didn’t last long: Uncle Feodor was sickly and passed just six years later in 1682. When would it be time for Peter?

65. To Kiss a King

Peter the Great famously broke court protocol during his 1717 visit to France: the towering Tsar picked up the child King Louis XV and planted a kiss on his pint-sized host. Peter sought to marry Louis to his daughter, but his plans to unite the Russian and French royal families never came to fruition. The kiss would have to do.

66. Sharing Is Caring

Siblings are no strangers to sharing, even when it comes to the throne of Russia. Peter first came to the throne in 1682 as a ten-year-old co-Tsar with his older half-brother, Ivan.

67. Big Sister is Watching You

Peter’s older half-sister Sophia served as Regent for most of his early reign. And she ran a very tight ship: Sophia drilled peepholes behind her brothers’ throne, where she would listen into their meetings and also whisper back information responses they were to repeat verbatim. In other words, she was a literal backseat ruler.

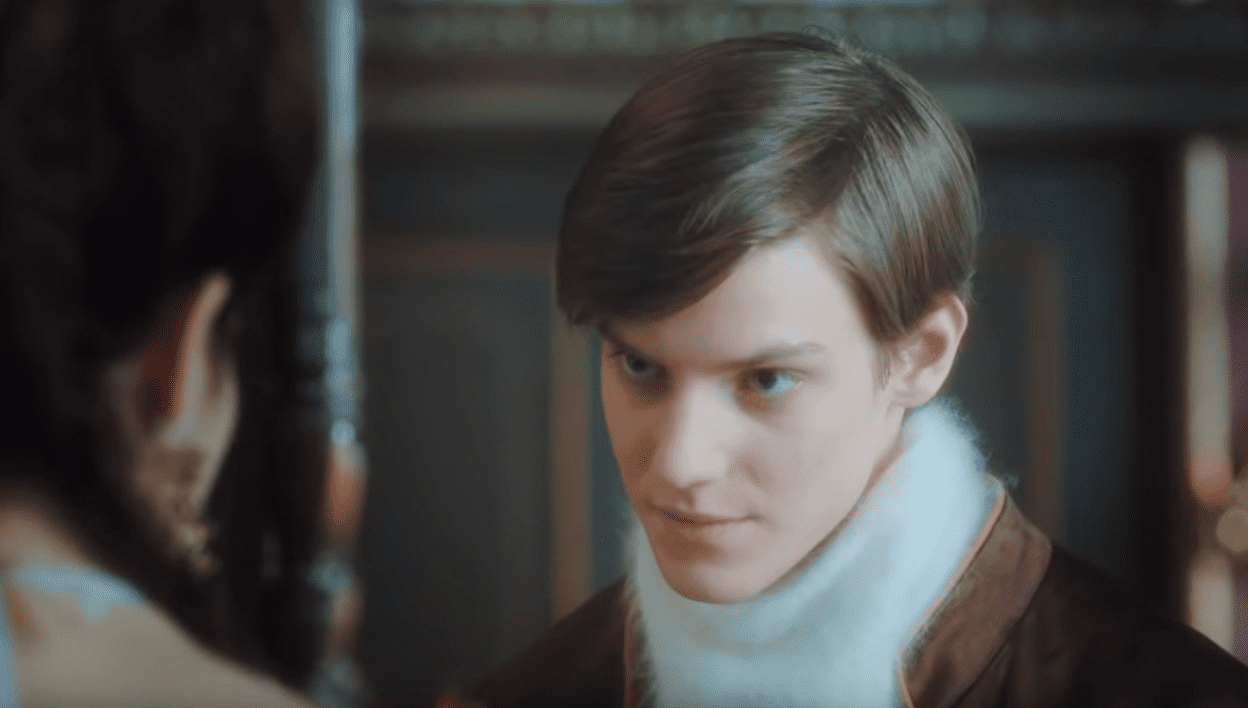

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

68. Don’t Mess With This Sis

In spring 1682, Peter’s boyhood battle for the throne violently came to a head when his 25-year-old half-sister Sophia launched a brutal rebellion against his side of the family. The ten-year-old Peter even witnessed some of his own family and friends being liquidated in the chaos.

69. Who Needs Thrones When You Have Boats

As a youth, Peter didn’t really resist his older sister’s control because he didn’t care for rulership that much. He much preferred his shipbuilding and sailing hobbies, as little boys are wont to prefer over diplomatic meetings.

70. I’m a Big Tsar Now

Eventually, Peter got sick of playing second-Tsar to his big sister. At the age of 17, he planned a coup against Sophia that ended in her deposition and exile to a convent. Peter and his other half-sibling, Ivan, however, remained allies and co-Tsars until Ivan’s passing. With Peter’s mother’s gone in 1694, Peter was 24 and finally ready to rule alone.

71. Head and Shoulders Above Them All

Even by our standards, Peter was a tall dude. At full height, he stood at 6'8" tall (203cm). This was balanced by oddly small hands and feet.

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

72. We Bet He Didn’t Feel So “Great” the Next Morning

According to legend, Peter the Great’s sojourn to England led to the invention the Russian Imperial Stout brew. The Tsar fell in love with English mead, but he couldn’t take any home with him before it spoiled. To rectify this, an English brewer kept adding more booze and hops to make it last longer, thereby creating the hot new brew that’s fit for a Tsar.

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

73. I Wanna Be Like You

For Peter—and for others—“modernization” meant "like the rest of Europe.” So as an early attempt to modernize the Russian government, Pete ordered all army and court officials to shave their beards and wear “modern” (see: French fashion-inspired) clothing. How did he make everyone shave you might ask? Well, he instituted a beard tax of course!

Authotities were even allowed to forcibly shave men in public if they refused to pay.

74. Sea Me Roar

Peter turned Russia into a real naval power for the first time in its history. With no Russian access to the Baltic, Black or Caspian Seas, Peter set out on his Azov campaigns against the Ottoman Empire in order to gain a foothold in the region (with all the army control it offered). After some failed first steps, it eventually worked. Peter inaugurated the port city of Taganrog in 1698, which became the first army base for the soon-to-be-legendary Russian Navy. Next stop: the world?

75. Master of Disguise

To prepare for his naval conquest against the Ottomans, Peter sent a group of ambassadors across Europe while secretly leading the expedition disguised as a simple carpenter named “Peter Mikhailov.” This initiative would be known as his “Grand Embassy,” which is ironic since it grandly fell on its face: the other relevant European powers were too preoccupied with their own wars to care about Peter’s grudge against the Ottoman Empire. But it wasn’t a total waste: Peter did learn a lot of about shipbuilding and everyday culture across Europe.

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

76. No Mercy, No Regrets

Peter was notoriously merciless to rebels. Managing to crush all rebellions waged against him during his reign, Peter didn’t settle for exile: he slaughtered mutineers in sadistic ways as a warning to others.

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

77. No Stopping Me Now

In 1700, Peter started a conflict with Sweden that lasted 24 years. His victory in this conflict—with a little help from Saxony and Denmark—truly set the stage for his legendary career, and for Russia’s rise as a European power.

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

78. Big Me in the City

In 1712, Peter moved Russia’s capital city from Moscow to Saint Petersburg (his namesake saint). The city had been founded in 1703 on the westernmost coast of the Baltic Sea to solidify the country’s newfound rights to the waterway.

79. I Called Dibs on First

The year 1712 also marked Russia’s official status as an Empire. As a result, Peter became known as “Peter the Great” and the first Tsar to be known as “Emperor of All Russia.”

80. I Do, I Guess

At the behest of his mother, Peter the Great married the daughter of a noble family in 1689, when he was just 17 years old. The bride’s name was Eudoxia Lopukhina, they had three sons, and were by all accounts very unhappily married.

81. Never Gonna Give You Up

Peter disliked his first wife Eudoxia from the start. He soon abandoned her for a Dutch mistress named Anna Mons, but the rejected Eudodixa would still send him letters begging for his nonexistent love.

82. Having Nun of It

In 1698, after nine years of marriage, Peter ended his miserable marriage to Eudoxia Lopukhina and exiled her to a convent. Euddoxia kept busy in seclusion and allegedly took a lover for herself named Stephen Glebov—a man who would later be drawn and quartered.

83. It’s Now or Never. Oh, You Chose Never…

After his divorce from his first wife, people believed Peter would marry his longtime mistress, Anna Mons. After all, they had been together for 12 years. However, by 1703, Ana feared Peter was falling out of love with her and therefore sought comfort in the arms of a Prussian ambassador to make Peter jealous. Eventually, the ambassador proposed to Anna and the two did get married. Awkward.

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

84. Some Way to Cool Off

The Tsar was initially furious to discover his mistress was carrying out her own affair with an ambassador. Even worse: the couple were considering marriage. In a rage, he revoked Anna Mons’s estate and placed not just her, but her mother, sister, and 30 friends under house arrest. Eventually, Peter did cool down enough to let the lovebirds marry in 1711.

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

85. A Cinderella Story

Peter elevated his peasant-born mistress to the position of his second wife. The couple secretly married sometime in late 1707, but they were officially wed in Saint Petersburg on February 9, 1712. The bride in question, Martha Skavronskaya, changed her name and would become known Catherine I of Russia.

86. Blondes Don’t Have More Fun

Peter’s second wife, Catherine, dyed her hair black to avoid reminding her husband of his previous mistress, Anna Mons. She was a blonde who spurned him and whose family paid the price.

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

87. He Picked His Side

Peter’s eldest son, Alexei Petrovich, hated his dad’s guts from the start. The Tsarevich was raised by his mother, who happened to be Peter’s deeply mistreated first wife, Eudoxia Lopukhina. As a result, Alexei found it hard to develop paternal bonds with the cause of his mother’s misery.

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

88. Daddy Issues

Although Tsarevich Alexei Petrovich was Peter’s eldest son, the boy spent most of his adult life thwarting his father’s efforts to mold Alexei into a worthy heir. In fact, after the birth of his own son, the future Peter II, Alexei tried to shirk his inheritance altogether. He asked Peter to pass the throne along and just let Alexei live a private (but luxurious) life with his own lover.

Peter would have preferred Alexei be a monk, just to be safe. Needless to say, it did not go well.

89. Where’s Jerry Springer When You Need Him?

The great Tsar put the friends and allies of his son Alexei under "questioning." He even dragged the boy’s mother out of religious sanctuary and charged her with adultery (they had been divorced for some time by that point, but I guess that doesn’t matter?). Why go to his trouble? Alexei continued to defy his own inheritance, even fleeing to Austria and thereby rebelling against Peter and the Russian government itself.

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

90. A Fatherly Touch

In 1715, Peter’s eldest son Alexei passed just two days after being sentenced to demise. It’s believed the wayward Tsar succumbed to interrogation-related injuries. Attempts had been made to make the Tsarevich “confess” to treason plots against his own father.

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

91. Ghosts of Son’s Past

After his son’s torturous demise (inflicted by daddy dearest himself), Peter’s new heir was his grandson, the future Peter II of Russia. By 1715, Peter the Great had managed to alienate or end most of his close family members: his older sister, his first wife, and now his late son. Unfortunately, grandson reminded Peter of the disgraced prodigal son Alexei.

As a result, the new Tsarevich was educated away from his grandfather in deep seclusion.

pinterest

pinterest

92. Secret Sickness

Throughout his life, Peter suffered from distinct facial tics that suggest he had epilepsy. It’s said his favored second wife, Catherine, had a talent for calming down his rages, both epileptic and non-epileptically induced.

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

93. Started From The Bottom Now They’re Here

Peter expected his army men to start at the lowest rank of army service and work their way up. It was how he had been educated, why shouldn’t everyone follow the Tsar’s example?

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

94. His Cup Floweth Over

While he was never a fully healthy man, the Tsar's body took a grim turn for the worse in 1723. The following year, he had to get surgery that removed four pounds of blocked urine from his body. Since we’re talking 18th-century surgery, none of that sentence was fun for anybody involved.

95. We Won’t Water This Down for You

In the end, Peter the Great passed at the age of 52 on 8 February 1725. Sitting on the throne for 42 years, he left behind a great empire and also a gangrene-infested bladder.

96. Let Me Finish That Thought…

Another legend says that Peter passed in the middle of writing his famously incomplete will. Dying of uremia (the kingly demise of urine pollution in his blood), it’s said he managed to scrawl “Leave all to…” but then passed out, only having enough energy to summon his daughter.

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

97. Following in Hubby’s Footsteps

Peter’s wife, Catherine, succeeded him on the throne. The Tsar had passed without naming any successor, so Empress Catherine seized power and began to represent the interests of elevated common folk, known as “the new men.” Her popularity led to a coup on her behalf, wherein she was crowned co-ruler of Russia. Unfortunately, she did not enjoy this power long—Catherine outlived Peter by only two years.

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

98. Best Foot Forward

In 1695, Tsar Peter fought as a foot soldier against the Ottoman Empire. As one of those guys with no chill, Peter believed the Turks could only be defeated in such intimate combat.

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

Peter the Great (1986), NBC Productions

99. Baywatch: Tsar Edition

A legend exists that Peter saved a pack of drowning army men himself by wading out into waist-deep water. On one hand, this seems exaggerated, because this was dated to when he was near demis. On the other hand, this was also dated to a brief period where he seemed to recover enough to go out and inspect his empire. Nevertheless, tale-tellers raise his exposure to the cold water in order to explain the continued (and deadly) bladder problems.

Tsarevich Aleksey (1996), Vitaliy Melnikov

Tsarevich Aleksey (1996), Vitaliy Melnikov

100. The Man Who Would be Tsar

Nicholas Alexandrovich Romanov was born in Alexander Palace, St. Petersburg, on May 18, 1868. The eldest son to Russian emperor Alexander III, Nicholas was heir to the Russian throne and a member of a royal lineage that included the royal families of Greece, Germany, Norway, Denmark, and England. No one realized it at the time, buy his passing sounded a demise knell for the Russian Royal Family.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

101. Not From Around Here

Nicholas’ family was not ethnically Russian—they were mostly of Danish and German heritage. Nicholas’ most recent Russian relative had been Grand Duchess Anna Petrovna, the daughter of Peter the Great. She passed over a century before his birth.

102. All in the Family

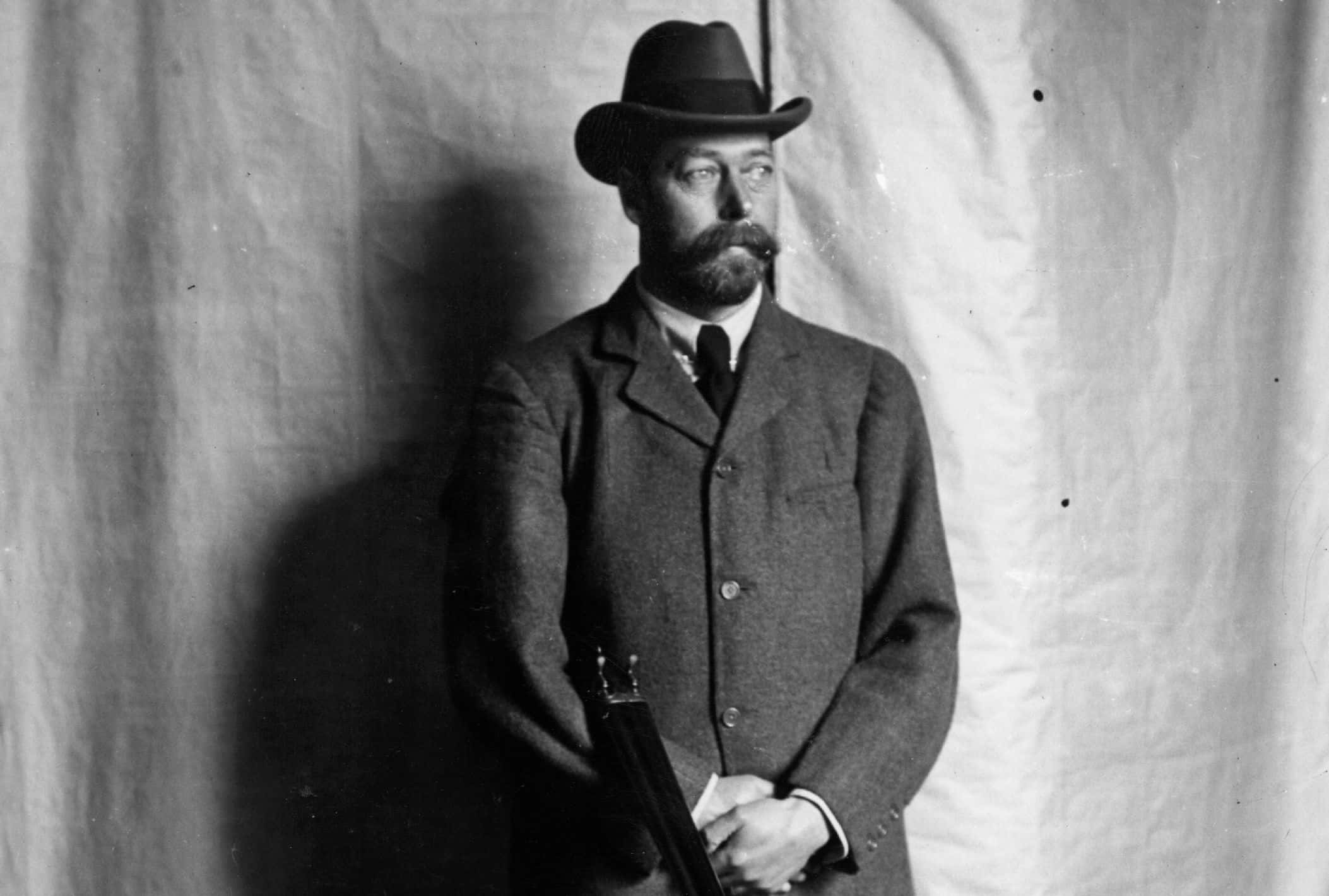

Nicholas was cousins to both England’s King George V and Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm II, and the three were close friends. Even at the height of hostilities during WWI, Nicholas addressed his official correspondences to “Georgie” and “Willie.”

Thomas Heinrich Voigt, Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Heinrich Voigt, Wikimedia Commons

103. Impersonating the King

Nicholas II and George V bore such a strong resemblance to each other that when Nicholas attended George V’s wedding, several guests confused the two. Even Queen Victoria, George's grandmother, noted the similarity.

104. Not Quite the Same

Another of Nicholas’s cousins, Paul Ilyinsky, was also a ruler of sorts. He was the mayor of Palm Beach, Florida.

105. Gap Year

It was customary for a future Tsar to see the Eurasian continent firsthand before taking the throne. Nicholas took his “Eastern Journey” in 1890, leaving from St. Petersburg and traveling 31,690 miles in a circumnavigation of all of Asia before ending up back where he started.

Wikimedia Commons, Ukhtomsky, Esper Esperovich

Wikimedia Commons, Ukhtomsky, Esper Esperovich

106. The Tsar with the Dragon Tattoo

Of all the countries he visited, Nicholas seemed to enjoy his time in Japan the most. He even got a tattoo to mark the visit. The tattoo—a black dragon on his right forearm—was done by traditional tattoo artists in Nagasaki.

107. Money Can’t Buy Happiness

At the time of his passing , Nicholas was worth $900 million, roughly the equivalent of $300 billion today. Were he alive today, Nicholas would be the richest man in the world three times over.

108. Jolly Old Saint Nicholas

In 1981, after heated debate, the Russian Orthodox Church named Nicholas II a saint. They extended the same status to the entire Romanov family and many of their most loyal servants. The Church stopped short of declaring Nicholas a martyr, however: his passing, they reasoned, was not the result of religious persecution, and in many ways, was brought on by his own actions.

109. Coming Home

In 1979, an amateur archaeologist uncovered the remains of several people at a site near Sverdlovsk. In 1998, DNA testing confirmed that the bodies were those of the Romanov family, including Nicholas II. The Romanovs were given a formal burial at St. Peter and Paul Cathedral, St. Petersburg, on July 17, 1998, 80 years after their execution.

110. Royal Courtship

At the wedding of his uncle, Grand Duke Sergei, in 1884, Nicholas met Princess Alix of Hesse and by Rhine, who was just 12 years old at the time. When Princess Alix visited St. Petersburg five years later, Nicholas fell in love with her and immediately began seeking her hand in marriage.

111. Happily Ever After

Though the feeling was mutual, Alix was reluctant to marry Nicholas: she was a devout Lutheran, while Nicholas was Russian Orthodox. With the demise of his father, and his impending ascension to the throne, Nicholas’ desire to marry Alix grew more and more urgent, and she finally relented. The two were married on November 26, 1894.

As Tsarina, Alix adopted the name Alexandra Feodorovna.

112. Too Much, Too Soon

Alexander III’s health began deteriorating rapidly in 1894. This decline was unexpected, as Alexander was still quite young. Very few people—including Nicholas himself—believed that the Tsarevich had been adequately prepared to take over. Nevertheless, Alexander III passed on October 20, 1894, leaving the inexperienced Nicholas to assume the throne.

113. More Than a Mouthful

Upon becoming Tsar, Nicholas II assumed the title “By the Grace of God, We Nicholas, Emperor and Autocrat of All the Russias, of Moscow, Kiev, Vladimir, Novgorod; Tsar of Kazan, Tsar of Astrakhan, Tsar of Poland, Tsar of Siberia, Tsar of Tauric Chersonesus, Lord of Pskov, and Grand Prince of Smolensk, Lithuania, Volhynia, Podolia, and Finland; Prince of Estonia, Livonia, Courland and Semigalia, Samogitia, Bielostok, Karelia, Tver, Yugor, Perm, Vyatka, Bogar and others; Sovereign and Grand Prince of Nizhni Novgorod, Chernigov, Ryazan, Polotsk, Rostov, Jaroslavl, Beloozero, Udoria, Obdoria, Kondia, Vitebsk, Mstislav, and Ruler of all the Severian country; Sovereign and Lord of Iveria, Kartalinia, the Kabardian lands and Armenian province: hereditary Sovereign and Possessor of the Circassian and Mountain Princes and of others; Sovereign of Turkestan, Heir of Norway, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein, Stormarn, Dithmarschen, and Oldenburg, and so forth, and so forth, and so forth.”

Friends called him Nicky, for short.

114. The Silver Screen

Nicholas’ coronation was filmed by a French journalist. It was the first film ever shot in Russia.

115. The Boss

Nicholas’ first order of business upon taking the throne was to declare he would entertain no discussions of introducing a constitutional monarchy, like in England. Despite rising demand among the Russian people, and against the advice of his own counsel, Nicholas officially declared that, as long as he was Tsar, he and he alone would rule Russia.

116. That’s Finnished

In 1899, Nicholas abolished Finland’s constitution and restricted their power to make laws. Finland was a Russian territory, but their autonomy had been honored by the Russian imperial government for nearly 100 years.

117. Anti-Semite

At the encouragement of the Russian Minister of the Interior, Russian Jews in Bessabaria were subjected to pogroms from 1903 to 1905. Nicholas publicly discouraged these pogroms, but he identified them as a useful tool in unifying non-Jewish Russians against a common cause. He would not formally denounce the antisemitic pogroms until 1911.

118. Good Work If You Can Get It

Nicholas oversaw the first Russian census in 1897, and even participated himself. Under occupation, Nicholas wrote “Owner of Russia.”

119. The Nobel King

At home, Nicholas’ reputation as an inexperienced, self-absorbed, and despotic ruler only continued to grow. On the international stage, however, Nicholas was seen as an inspiring, progressive leader. In 1899, Nicholas staged the Hague Peace Conference, in hopes of slowing the industrial arms race and developing conventions for peaceful conflict resolution between nations.

For his efforts, Nicholas was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1901.

120. Utter Defeat

Nicholas’ commitment to world peace was tested in 1904 when Russia went to combat with Japan. Both countries had expansionist policies and began fighting over control of parts of Korea and Manchuria. The Japanese quickly gained the upper hand, and Nicholas sued for peace in 1905—a humiliating defeat for the Tsar.

121. Sunday, Bloody Sunday

That same year, Georgy Gapon marched on St. Petersburg. Gapon, a priest and labor leader, was accompanied by a veritable army of Russia’s working class. They had hoped to present the Tsar with a petition, requesting better working and living conditions. When they arrived at the palace, army battalion opened fire, liquidating 92 people and wounding hundreds more.

122. In Absentia

The events of “Bloody Sunday” earned Nicholas widespread condemnation. Even British politicians voiced their concerns, with the Prime Minister himself calling the Tsar “a common murderer.” In truth, Nicholas did not give the order to fire—he wasn’t even at the palace at the time. Instead, Nicholas had been persuaded to wait in Tsarskoye Selo until the crowd dispersed.

123. Gloom and Duma

Bloody Sunday forced Nicholas to reconsider his commitment to autocracy. In August 1905, Nicholas announced that he was convening the Duma, an elected advisory council. But while the Duma was stocked with some truly radical voices, it was essentially toothless: Nicholas ignored many of their demands and carried on just as he had before.

124. Royal Blood

Like much of Europe’s royal class, Nicholas’s son Alexei was afflicted with hemophilia. Nicholas and Alexandra hoped to cure Alexei of the disease. After several failed consultations with doctors throughout Europe, the royal couple turned to Grigori Rasputin, an obscure Siberian monk. Rasputin would hold significant influence over the Tsarina in the last years of Nicholas’ reign.

125. Mind Your Own Business

Contrary to popular opinion, however, Rasputin held very little sway over the Tsar’s political decisions. While Nicholas was grateful for Rasputin’s help with Alexei, he kept the mysterious stranger at arm’s length. When Rasputin warned Nicholas to stay out of World WI, Nicholas advised Rasputin to stay out of politics.

126. Losing the Conflict

Rasputin may have been right. Nicholas II ordered his army to march into Germany. While the Russian army was massive—more than four million strong—it was poorly equipped and poorly prepared. Some of the men didn’t even have boots. 3.3 million Russians passed in the conflict , heavy losses for which the public, once again, blamed Nicholas II.

127. The Beginning of the End

By February 1917, Russia had reached a breaking point. Rising inflation, not to mention the frozen winter, made food all but impossible to obtain; the implementation of the Duma hadn’t signaled any great shift towards democratic rule, and the heavy losses incurred during the conflict threw the country into despair. Riots began in St. Petersburg on February 23rd, the mob chanting “Down with the Tsar!”

128. Coup

Russia’s army were not immune to the terrible conditions throughout the country. As the mob advanced through the streets of St. Petersburg, more than 60,000 army men joined them.

129. Fired!

Nicholas was powerless to restore order. With no army and the Duma dissolved, Russia was in chaos. On March 12, the Soviet and the Duma formed a provisional government. Their first order of business: demand the immediate abdication of the Tsar.

130. The End of an Era

In 1917, after the upheaval of the February Revolution, Nicholas abdicated and ceded the throne to his son, Alexei. Almost immediately, he abdicated on Alexei’s behalf. This left Nicholas’ brother, Michael, in charge, but Michael refused to accept the throne unless the country voted to remain a monarchy. After three centuries, Russia’s tsarist monarchy had come to an end.

Sophie Hirschmann, Wikimedia Commons

Sophie Hirschmann, Wikimedia Commons

131. Nowhere to Go

Following his abdication, Nicholas and his family were offered sanctuary with his cousin, King George V of England. However, George rescinded his offer when he realized that housing the Tsar might lead to a revolution in England as well. France also declined to provide a home for the Romanovs, and they were forced to wander from residence to residence throughout Russia and Siberia.

132. On a Budget

The Romanovs moved around Russia in considerable comfort. They stayed at winter palaces, or the homes of provincial governments. Things became considerably more difficult for the Royal family after the October Revolution. The new government, led by Vladimir Lenin, severely restricted the Romanov’s movements and access to luxuries.

133. House Arrest

The Romanovs were eventually moved to “the House of Special Purpose,” a house near Yekaterinburg which had been seized by the Soviet government. There, they were forced to subside on army rations. For Nicholas, the final humiliation came when he received an order that he could no longer wear epaulets, the final, petty symbol of his former authority.

134. The Demise of the Tsar

Shortly after midnight, on July 17, 1918, the Romanovs were brought to the cellar of the house, under the pretext of protection from approaching Bolshevik mobs. The Romanovs entered the cellar, followed immediately by a squad of gunmen. The Romanovs, their doctor, and three servants were executed. According to Bolshevik Peter Ermakov, Nicholas’ last words were “You know not what you do.”

135. Blood Diamonds

Nicholas passed almost instantly from his wounds. His daughters were not so lucky: their dresses, lined with secreted diamonds and jewels, deflected the executioners’ bullets. So, instead, the executioners turned on them with bayonets, then finally shot them in the head.

136. Heir Apparent

Nicholas was just 12 years old when his grandfather, Alexander II, was liquidated. Following an explosion attack by Nihilists, Alexander II was taken to the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg, where Nicholas witnessed his grandfather’s final moments. Nicholas’ father, Alexander III, assumed the throne, and Nicholas was named heir-apparent, or Tsarevich.

137. A Close Shave

Nicholas loved Japan, but the feeling was not necessarily mutual. While in Ōtsu, Nicholas was charged by one of his law enforcement escorts, armed with a katana. The officer, Tsuda Sanzō, was wrestled to the ground by two rickshaw drivers, and Nicholas escaped with just a small scar on his forehead. The rickshaw drivers were rewarded handsomely by both the Japanese and the Russian governments, while Tsuda was given life in correctional facility. No reason for the attack was ever given.

138. All Apologies

The Ōtsu Incident was a great embarrassment to the Japanese people, who were hoping the visit would ease tensions between the two nations. Japan’s Emperor Meiji even went so far as to ban the names “Tsuda” and “Sanzō.” Nevertheless, Nicholas cut his trip short; the humiliation of the incident led one young Japanese woman to cut her own throat in front of the Kyoto Prefectural Office.

Wikimedia Commons, Takahashi Yuichi

Wikimedia Commons, Takahashi Yuichi

139. The Khodynka Tragedy

Nicholas II was crowned on May 26, 1896. 100,000 Russians gathered in Khodynka Field to witness Nicholas take the throne, but the event was marred by tragedy. Rumors that there would not be enough food and drink for such a crowd led to a stampede. More than 1,300 people passed in what would be known as the Khodynka Tragedy.

140. It’s My Party

Rather than risk offending his most important allies, Nicholas was advised to attend a celebration being held in his honor that evening at the French embassy, rather than mourn with the public. Nicholas’ apparent indifference to the tragedy at Khodynka infuriated the Russian public, and his reputation never really recovered.