Franklin Expedition Unraveled

The Arctic keeps its secrets well. But sometimes, modern science cracks open tales that have leered over us for generations. DNA analysis recently revealed something incredible about explorers who vanished in 1845.

DNA Breakthrough

In September 2024, a team from the University of Waterloo and Lakehead University extracted genetic material from a preserved tooth connected to a jawbone found on King William Island in Canada's Nunavut territory. This finally gives a name to one of history's tragic Arctic disasters.

Stephen J. Trafton, Wikimedia Commons

Stephen J. Trafton, Wikimedia Commons

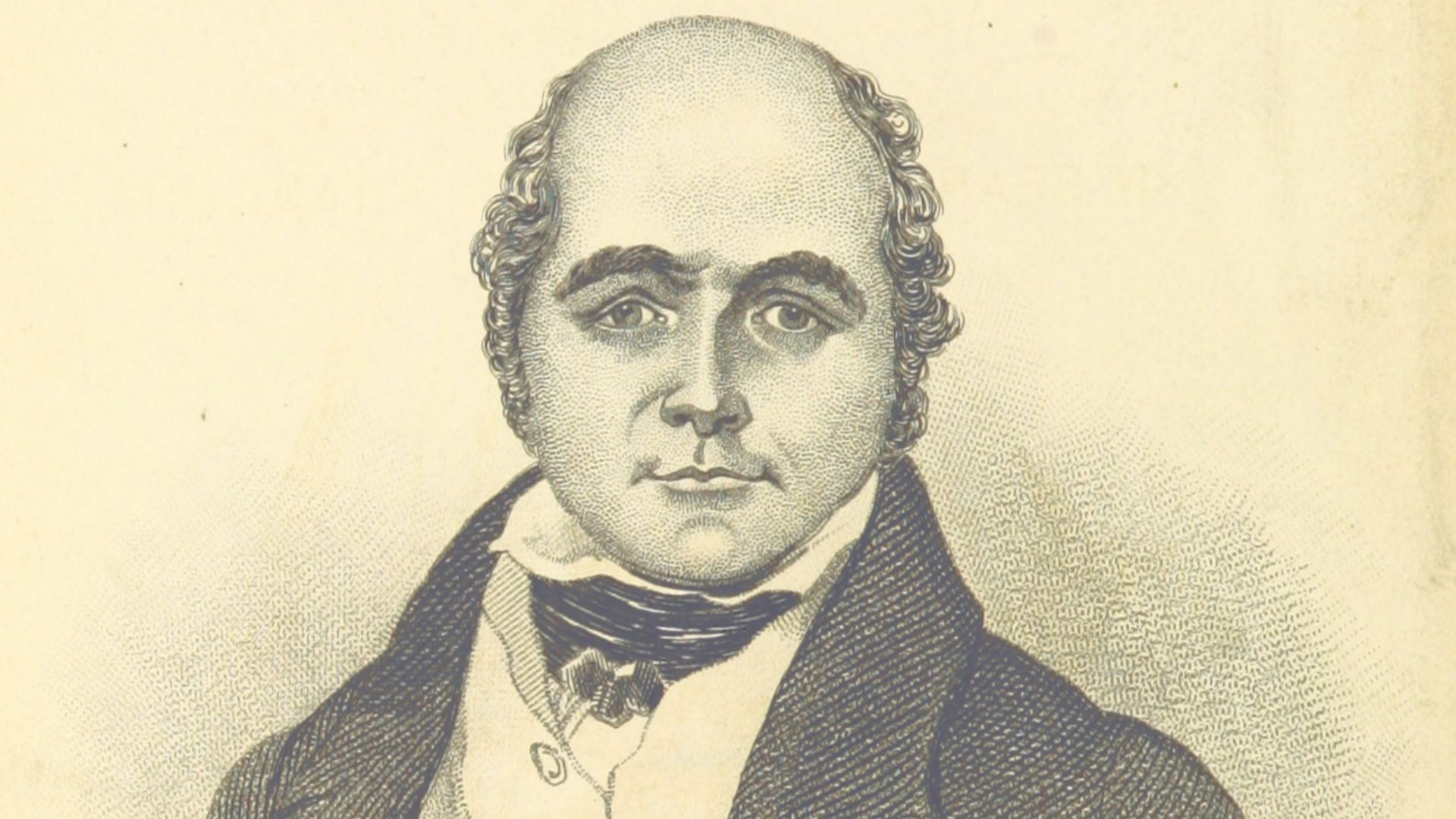

Fitzjames Identified

As per reports, the remains belonged to Captain James Fitzjames, a senior officer aboard HMS Erebus who was born on July 27, 1813. Fitzjames had helped lead 105 survivors from their ice-trapped ships in April 1848, attempting a desperate escape from the Arctic.

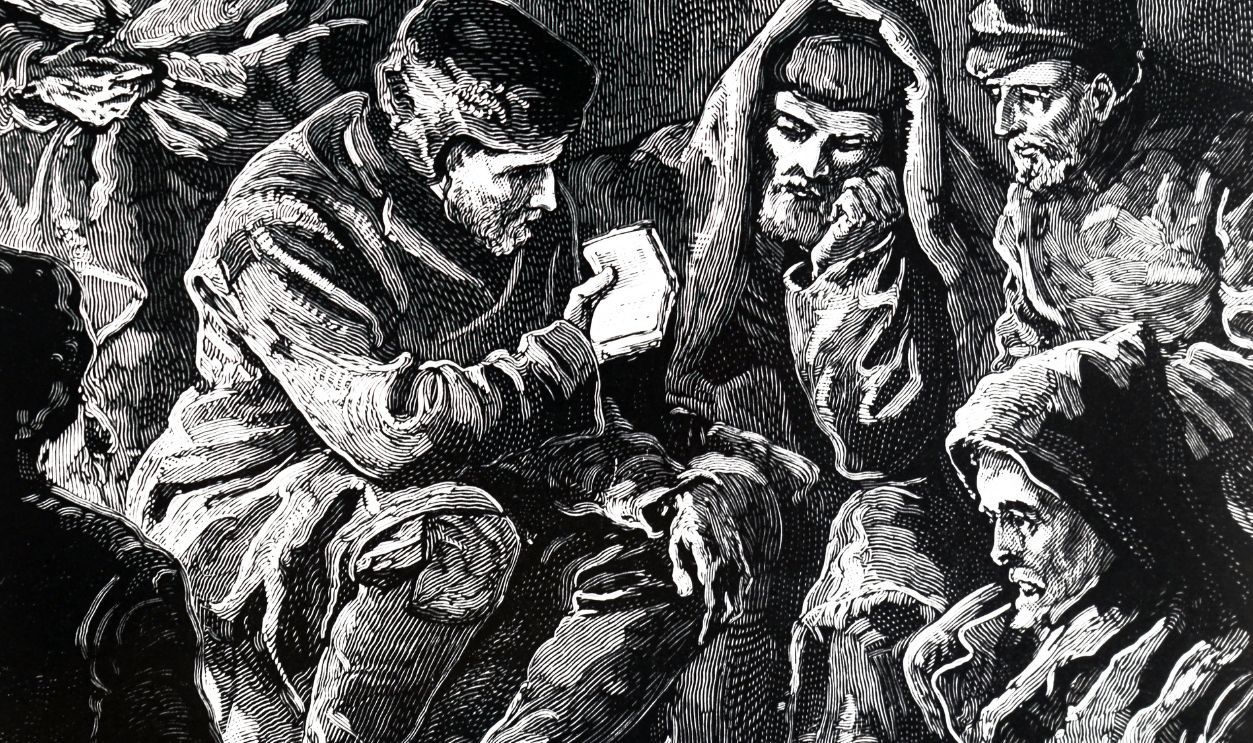

Cannibalism Confirmed

The DNA identification revealed a horrifying truth that Inuit people had reported for over a century, but Europeans refused to believe. Fitzjames' remains showed clear evidence of cannibalism, with multiple cut marks on his mandible, indicating his body was subjected to desperate survival measures.

Cut Mark Analysis

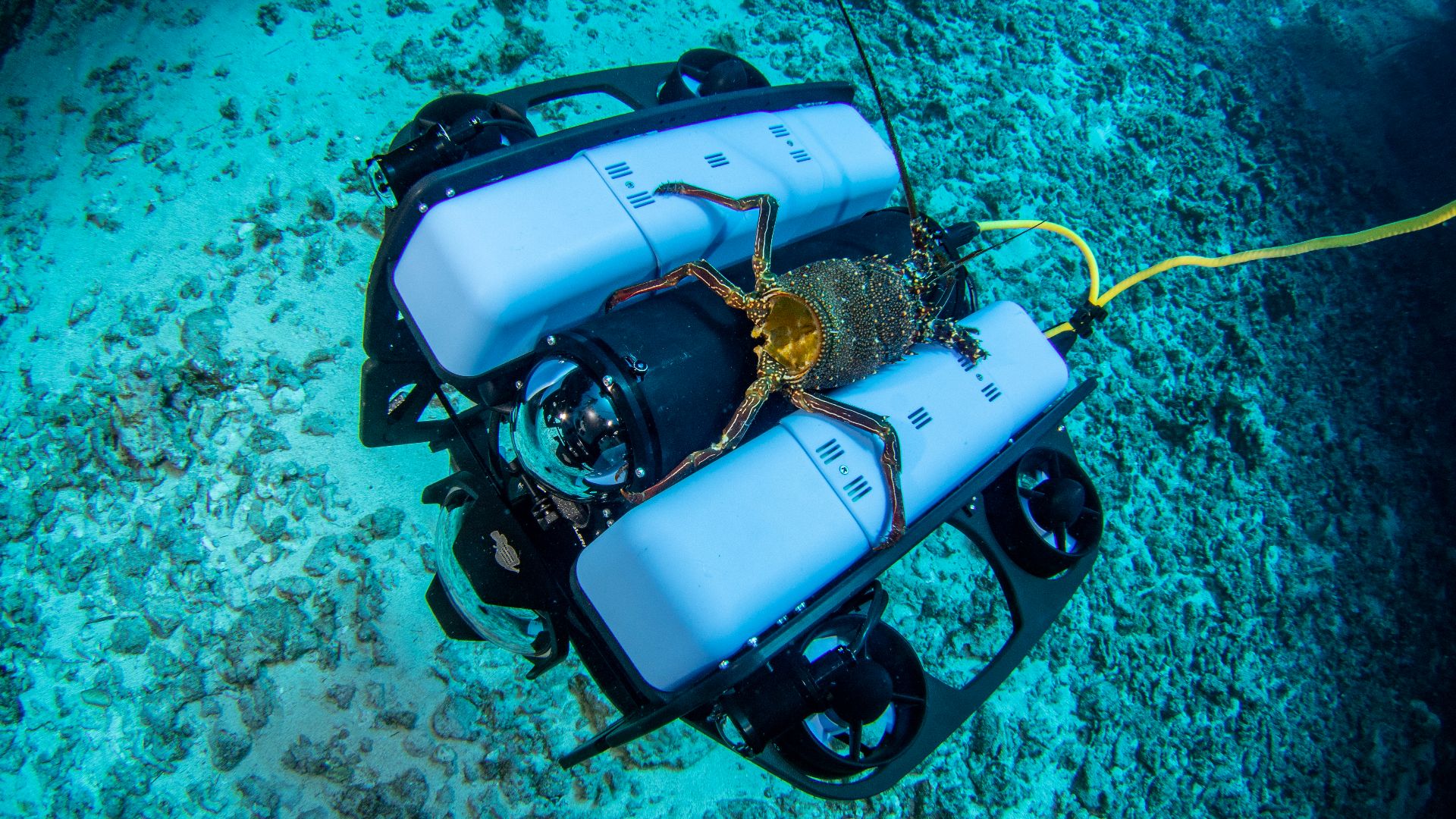

Apparently, a detailed forensic examination proved that the cut marks on Fitzjames' mandible were made with metal tools, likely knives carried by the expedition members. The mandible exhibited V-shaped grooves with parallel striations under scanning electron microscopy (SEM), consistent with metal blades.

Tadeáš Bednarz, Wikimedia Commons

Tadeáš Bednarz, Wikimedia Commons

Island Geography

William Island sits in Canada's Arctic Archipelago, surrounded by treacherous waters that proved fatal to Franklin's expedition. The island measures approximately 13,111 square kilometers, making it Canada's 15th-largest island. Its harsh geography includes the James Ross Strait to the northeast.

Original uploader was Kennonv at en.wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

Original uploader was Kennonv at en.wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

Island Geography (Cont.)

Similarly, the Victoria Strait lies to the west, and Simpson Strait to the south, creating a maze of ice-choked waterways that trapped the expedition ships. Low-lying, windswept terrain with minimal vegetation, Permafrost, and a short summer season characterize King William Island’s geography.

Ansgar Walk, Wikimedia Commons

Ansgar Walk, Wikimedia Commons

Archaeological Findings

The archaeological site on this island, designated NgLj-2, contained 451 bones from at least 13 Franklin expedition sailors found since the early 1990s. In 1993, archaeologist Margaret Bertulli led a team that thoroughly investigated and documented the site using contemporary archaeological methods.

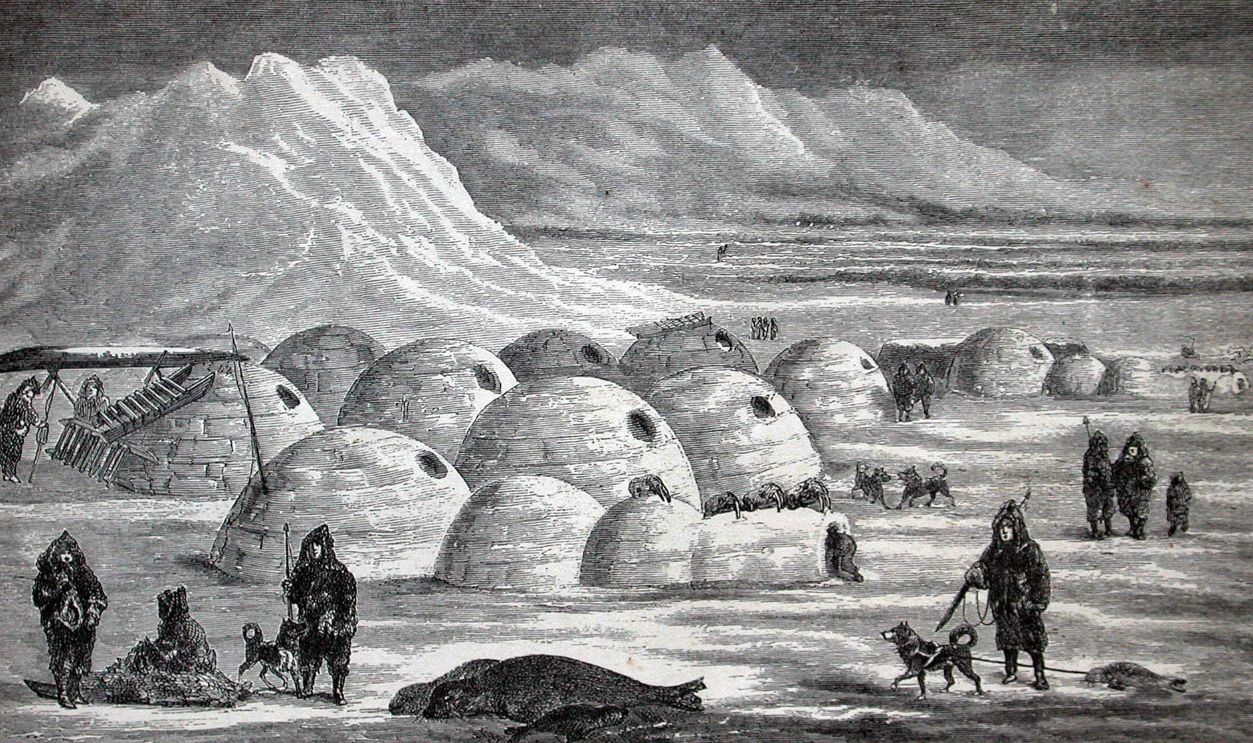

The Illustrated London News, ILN staff Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

The Illustrated London News, ILN staff Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

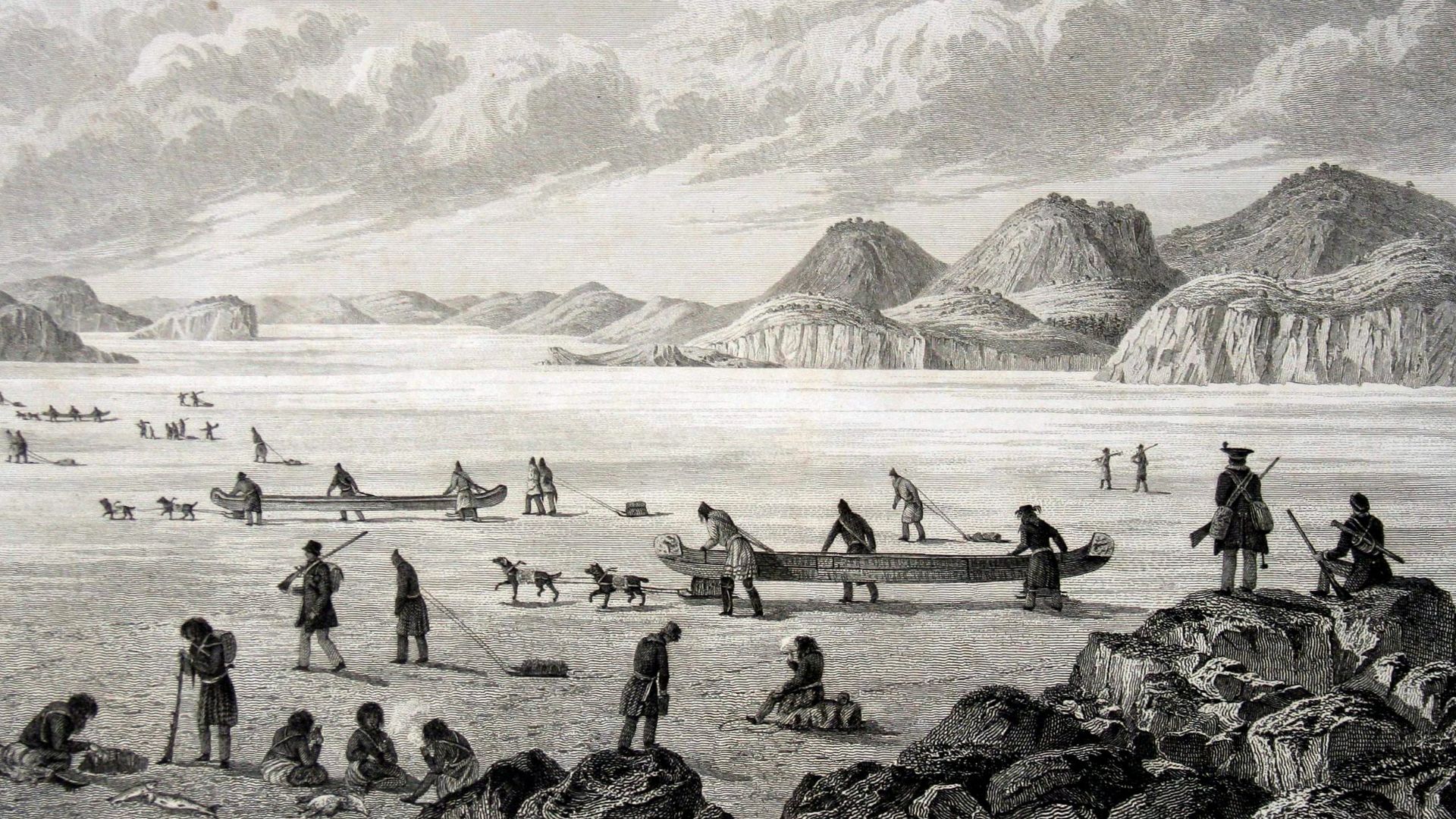

NgLj-2

This area was first unearthed in 1992 by Franklin scholar Barry Ranford and his colleague Mike Yarascavitch, who found human skeletal remains and artifacts suspected to belong to these members. The location closely matches the physical description of what was previously known as McClintock’s “boat place”.

Durand-Brager, Wikimedia Commons

Durand-Brager, Wikimedia Commons

Bone Collection

Researchers carefully cataloged hundreds of bone fragments scattered across the western shores of King William Island. The bone collection includes skulls, mandibles, vertebrae, and limb bones, many showing evidence of extreme weather exposure and animal scavenging over the past 176 years.

Stephen Trafton, Wikimedia Commons

Stephen Trafton, Wikimedia Commons

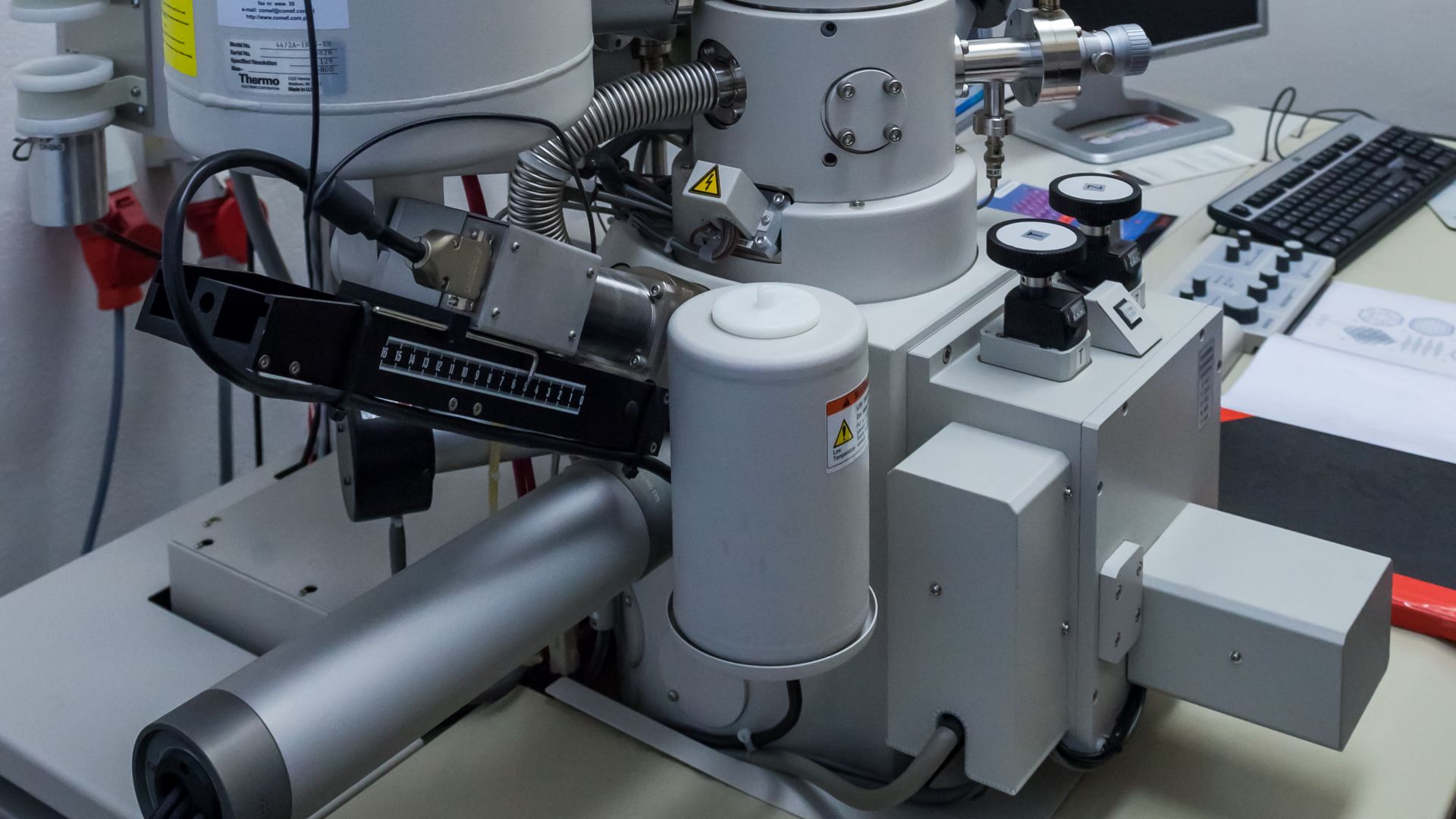

Y-Chromosome Matching

However, the breakthrough identification came through Y-chromosome DNA analysis, which traces direct paternal lineage through generations without genetic recombination. Scientists carefully extracted Y-DNA from a well-preserved molar belonging to a sailor, which is less prone to environmental degradation than other tissues.

Y-Chromosome Matching (Cont.)

Basically, DNA samples were collected from 25 living male descendants of Franklin expedition crew members. The Y-DNA from the molar was then compared with these modern samples to find a match. This provided the first-ever genetic identification of one of the members from skeletal remains.

Christoph Bock, Max Planck Institute for Informatics, Wikimedia Commons

Christoph Bock, Max Planck Institute for Informatics, Wikimedia Commons

Living Descendant

Interestingly, the DNA match connected Fitzjames to Nigel Gambier, his second cousin five times removed, who provided the critical genetic sample that confirmed the identification. Gambier descends from James Gambier, Fitzjames' great-grandfather, through two of Gambier's sons. This genealogical connection spans nearly two centuries.

Joseph Slater, Wikimedia Commons

Joseph Slater, Wikimedia Commons

Aristocratic Heritage

The Gambier family represented Britain's naval and diplomatic elite, wielding considerable influence in 19th-century society through their distinguished service record. This well-connected family of diplomats and naval officers provided Fitzjames with opportunities for advancement in the Royal Navy despite his illegitimate birth status.

Nicholas Pocock, Wikimedia Commons

Nicholas Pocock, Wikimedia Commons

Status Irrelevance

However, the consumption of a reputed senior officer proves that neither military rank nor social status protected them during the expedition's final desperate days. Traditional naval hierarchy collapsed completely under extreme survival conditions, with starving sailors treating their captain's remains no differently.

Carl Steffeck, Wikimedia Commons

Carl Steffeck, Wikimedia Commons

John Gregory

Before Fitzjames, only one other member of the 105 survivors had been positively identified through DNA analysis. In 2021, the same research team successfully identified John Gregory, an engineer aboard HMS Erebus, using similar genetic techniques. Gregory's recognition proved the effectiveness of the methodology.

Painted by G. Chalmers. Eng. by Wm. Howison., Wikimedia Commons

Painted by G. Chalmers. Eng. by Wm. Howison., Wikimedia Commons

Scientific Team

The identification breakthrough resulted from collaboration between Douglas Stenton from the University of Waterloo, Stephen Fratpietro from Lakehead University's Paleo-DNA laboratory, and Robert Park, a Waterloo anthropology professor. This interdisciplinary team combined expertise in Arctic archaeology, ancient DNA extraction, and forensic anthropology.

Memorial Placement

After the procedure, Fitzjames' remains were respectfully returned to King William Island and placed in a commemorative cairn alongside the bones of twelve other Franklin expedition sailors. A commemorative plaque marks this solemn site where these brave explorers now rest permanently.

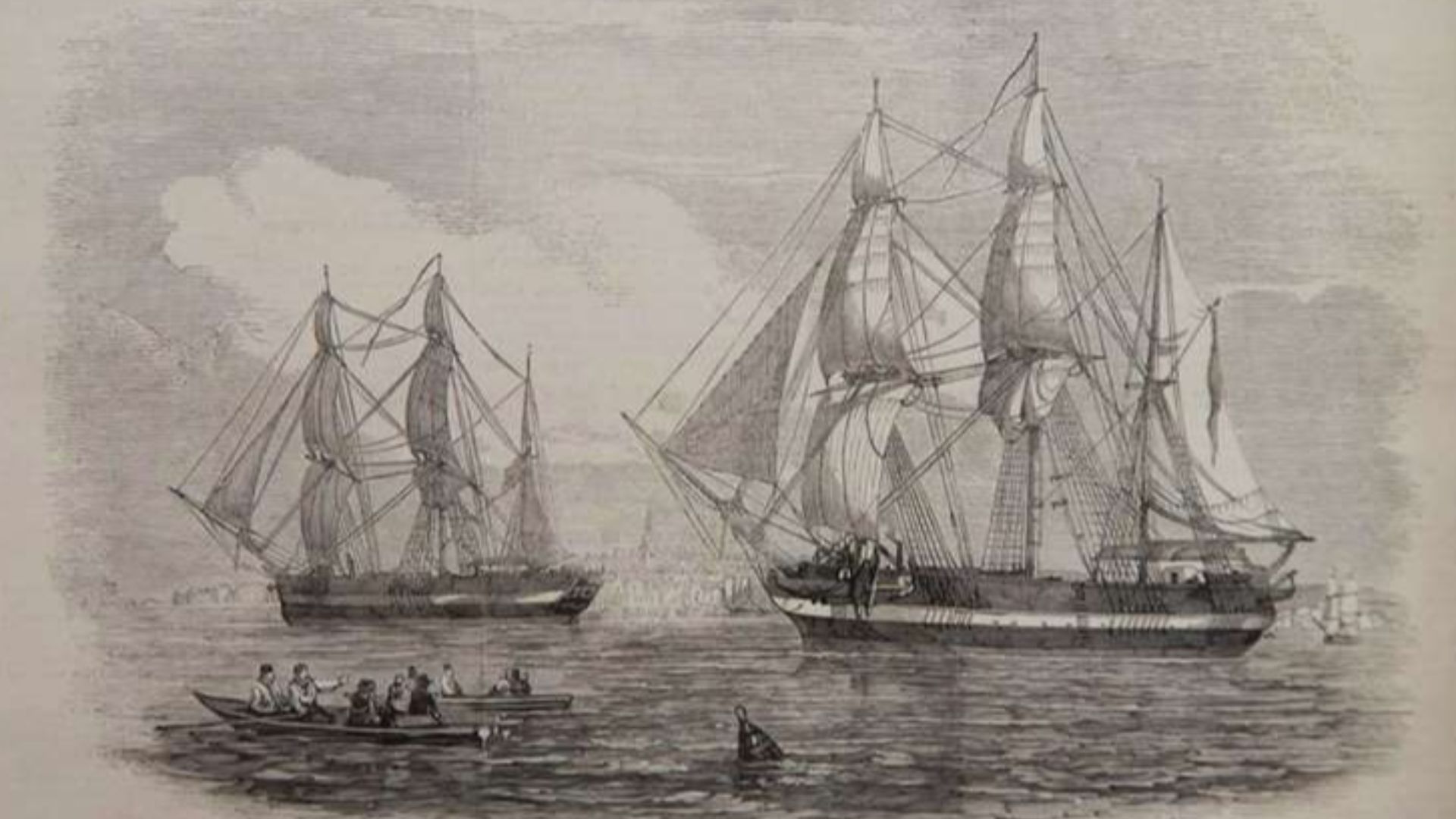

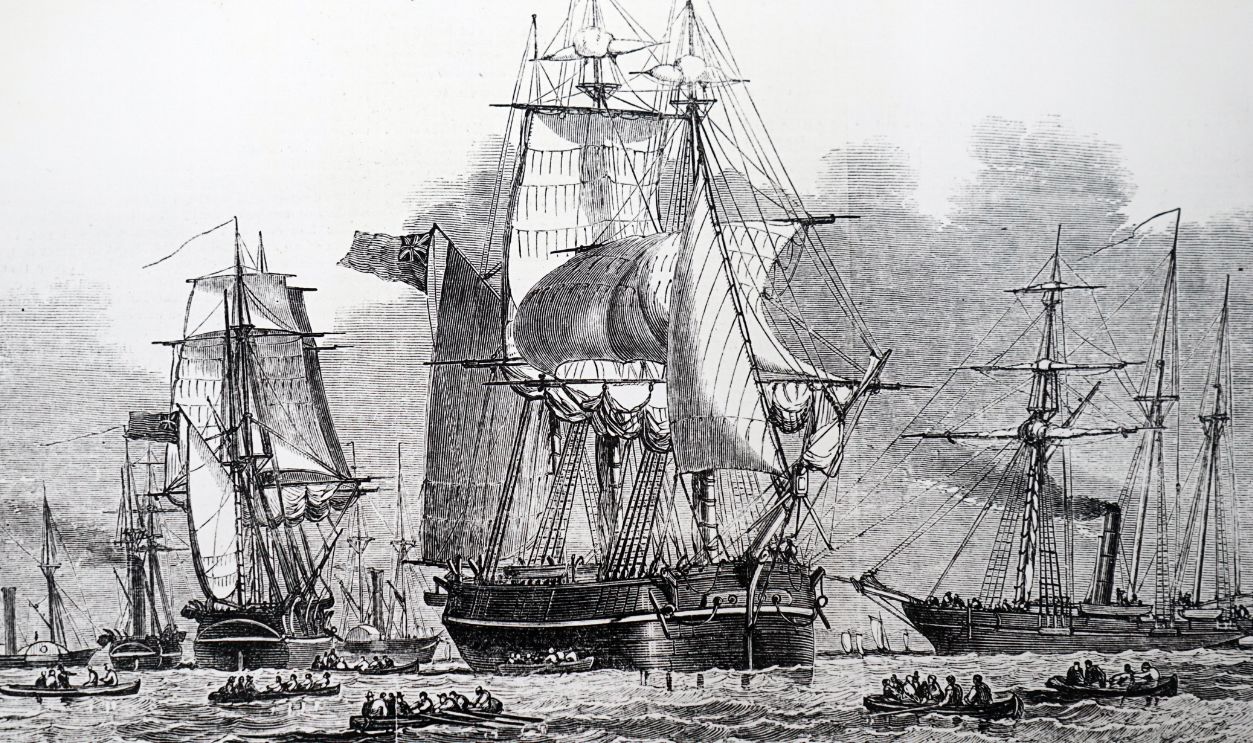

The Franklin Expedition

Sir John Franklin’s 1845 Arctic expedition is widely regarded as the pinnacle of British naval exploration in the nineteenth century. The mission set out with two state-of-the-art ships—HMS Erebus and HMS Terror—both specially reinforced to withstand the crushing pressure of Arctic ice.

The Franklin Expedition (Cont.)

These vessels were equipped with advanced technology for the era, including steam engines, retractable screw propellers, and extensive provisions designed to last several years. The expedition’s crew consisted of 129 officers and men, carefully chosen for their skills and experience in the challenging polar environment.

François Musin, Wikimedia Commons

François Musin, Wikimedia Commons

John Franklin

Sir John Franklin himself was an accomplished and experienced polar explorer. He had already led two previous Arctic expeditions, earning acclaim for his leadership and notoriety for the hardships his men endured. Despite his experience, the Royal Navy selected Franklin somewhat reluctantly for this ambitious voyage.

Advanced Technology

HMS Erebus and HMS Terror featured innovations, including converted railway locomotive engines for steam propulsion, reinforced iron-plated hulls, internal heating systems, and retractable propellers. The ships carried extensive libraries with over 1,000 books and sophisticated scientific instruments for magnetic observations.

Kerry Raymond, Wikimedia Commons

Kerry Raymond, Wikimedia Commons

1845 Departure

The expedition departed Greenhithe on May 19, 1845, with great fanfare. The Admiralty had invested heavily in provisions, along with equipment and crew selection, in order to create unprecedented confidence that this expedition would succeed where centuries of previous attempts had failed.

Universal History Archive, Getty Images

Universal History Archive, Getty Images

Provisions Planning

Franklin's ships carried three years' worth of carefully planned provisions, such as 8,000 tins of preserved food, salt-cured meat, pemmican, and live cattle. The tinned food contract was awarded to Stephen Goldner just seven weeks before departure, forcing rushed production that later proved problematic.

Niranjan Arminius, Wikimedia Commons

Niranjan Arminius, Wikimedia Commons

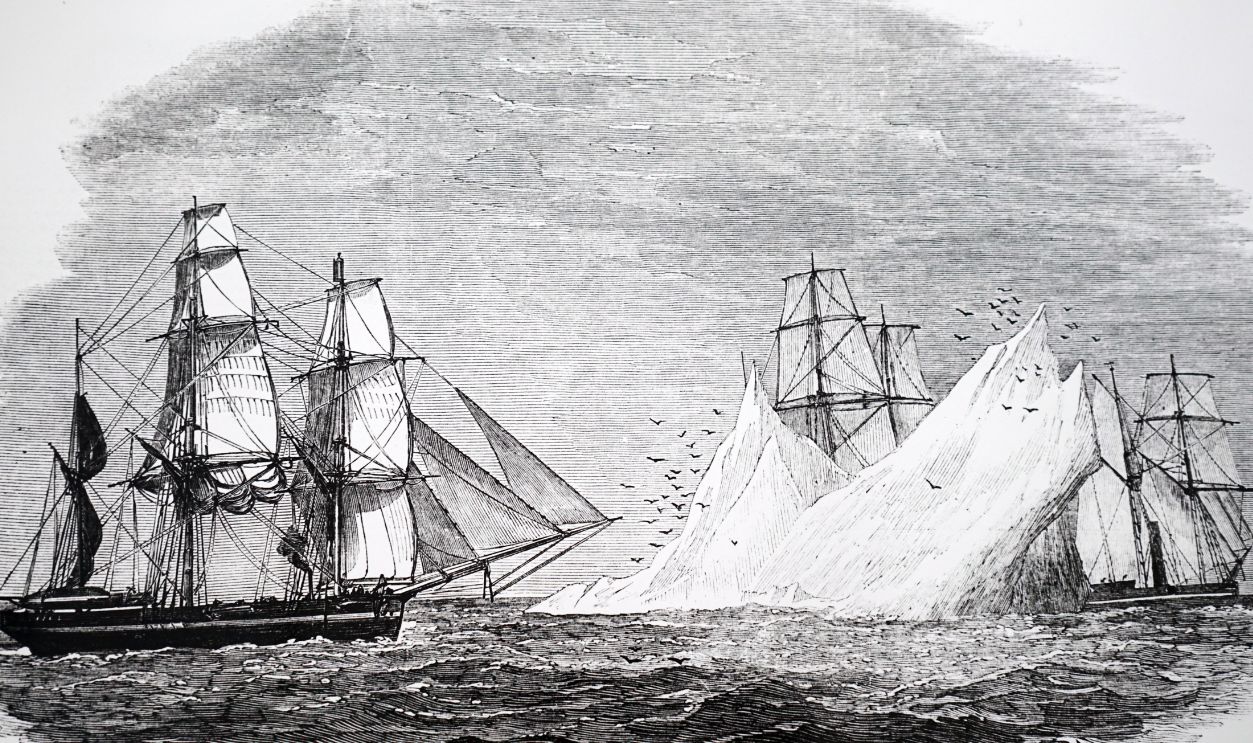

Ice Entrapment

However, in September 1846, after successfully navigating through the Arctic’s challenging waters, both HMS Erebus and HMS Terror became permanently trapped in pack ice northwest of King William Island in Victoria Strait. The ships remained locked in the ice for more than a year.

Universal History Archive, Getty Images

Universal History Archive, Getty Images

Ice Entrapment (Cont.)

The relentless grip of the ice forced the crew to endure two consecutive winters in this desolate location, with the vessels slowly drifting southward along with the shifting ice flows. During this time, crew members died steadily from cold, disease, and, of course, starvation.

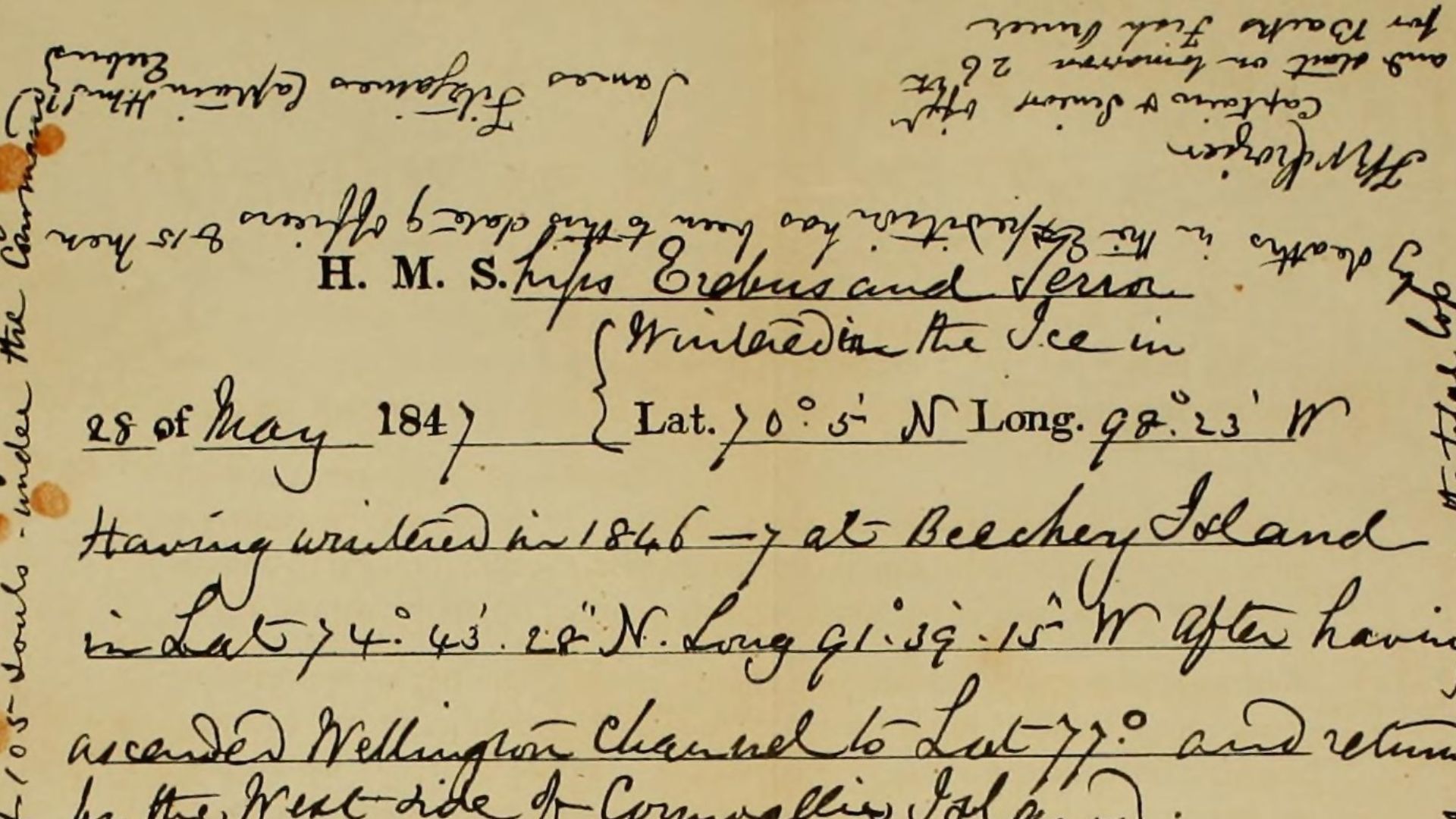

Franklin's Demise

Sir John Franklin passed away on June 11, 1847, after his ships had been trapped in ice for nearly a year. His demise left Francis Crozier, captain of HMS Terror, in overall command of the expedition, while James Fitzjames assumed command of HMS Erebus.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Franklin's Demise (Cont.)

John Franklin’s tragic passing away was later recorded in the famous “Victory Point Note,” which was discovered by subsequent search expeditions. The note confirmed that by the time of Franklin’s passing, nine officers and fifteen men had also perished.

Ship Abandonment

On April 22, 1848, after being trapped in ice for one year and seven months, the surviving crew finally abandoned both HMS Erebus and HMS Terror. By this point, 24 men had already died, including nine officers. The decision to leave their ships represented a desperate last resort.

Universal History Archive, Getty Images

Universal History Archive, Getty Images

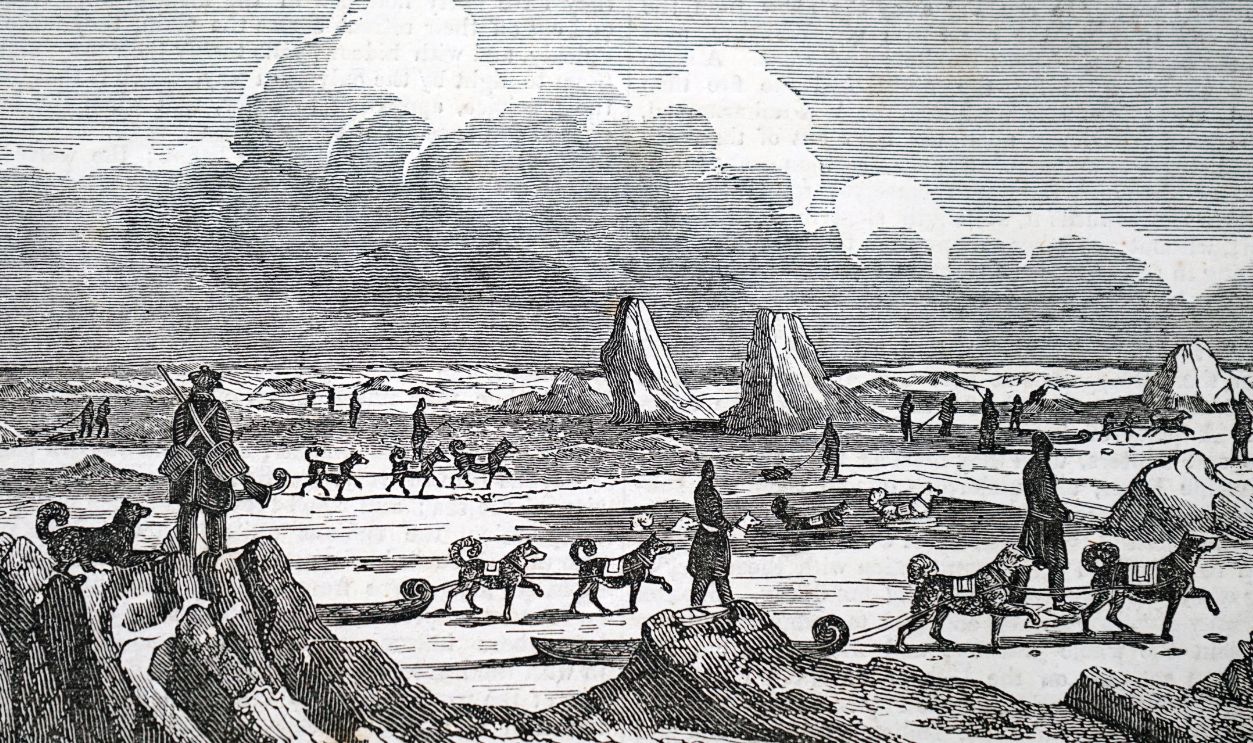

Western Coastline March

The 105 survivors began their doomed march along King William Island's western coastline, hauling heavy sledges loaded with supplies toward the Canadian mainland. This route proved tragically inappropriate, as the west passage remained ice-choked year-round, while the eastern route regularly cleared during summer months.

Jeffdelonge, Wikimedia Commons

Jeffdelonge, Wikimedia Commons

Western Coastline March (Cont.)

Their path led them directly into some of the Arctic's most unforgiving terrain and weather conditions. Led by Crozier, it was a grueling overland journey across King William Island and toward the Back River (also known as the Great Fish River).

NicolasPerrault, Wikimedia Commons

NicolasPerrault, Wikimedia Commons

Complete Disaster

Not a single member of Franklin's expedition survived the Arctic ordeal, making it the most catastrophic polar exploration disaster in history. The 129 officers and men who had departed England with such confidence and advanced equipment all perished in the Canadian Arctic.

Universal History Archive, Getty Images

Universal History Archive, Getty Images

Victory Point Note

Well, the journey's final written record, uncovered in 1859, was penned by James Fitzjames on April 25, 1848, at Victory Point on King William Island. This document reported Franklin's demise, the ships' abandonment, and the crew's plan to march toward Back River on the mainland.

Victory Point Note (Cont.)

This final written record was indeed found in 1859 by Lieutenant William Hobson during the McClintock Arctic expedition. The note was said to be in a stone cairn on the northwestern coast of King William Island, just south of Victory Point.

Stephen Pearce, Wikimedia Commons

Stephen Pearce, Wikimedia Commons

Search Missions

Between 1848 and 1859, over 30 search expeditions attempted to locate Franklin's missing ships and crew. These missions explored thousands of miles of Arctic coastline, and were some of history's largest rescue efforts. They even mapped previously unknown territories while searching for clues.

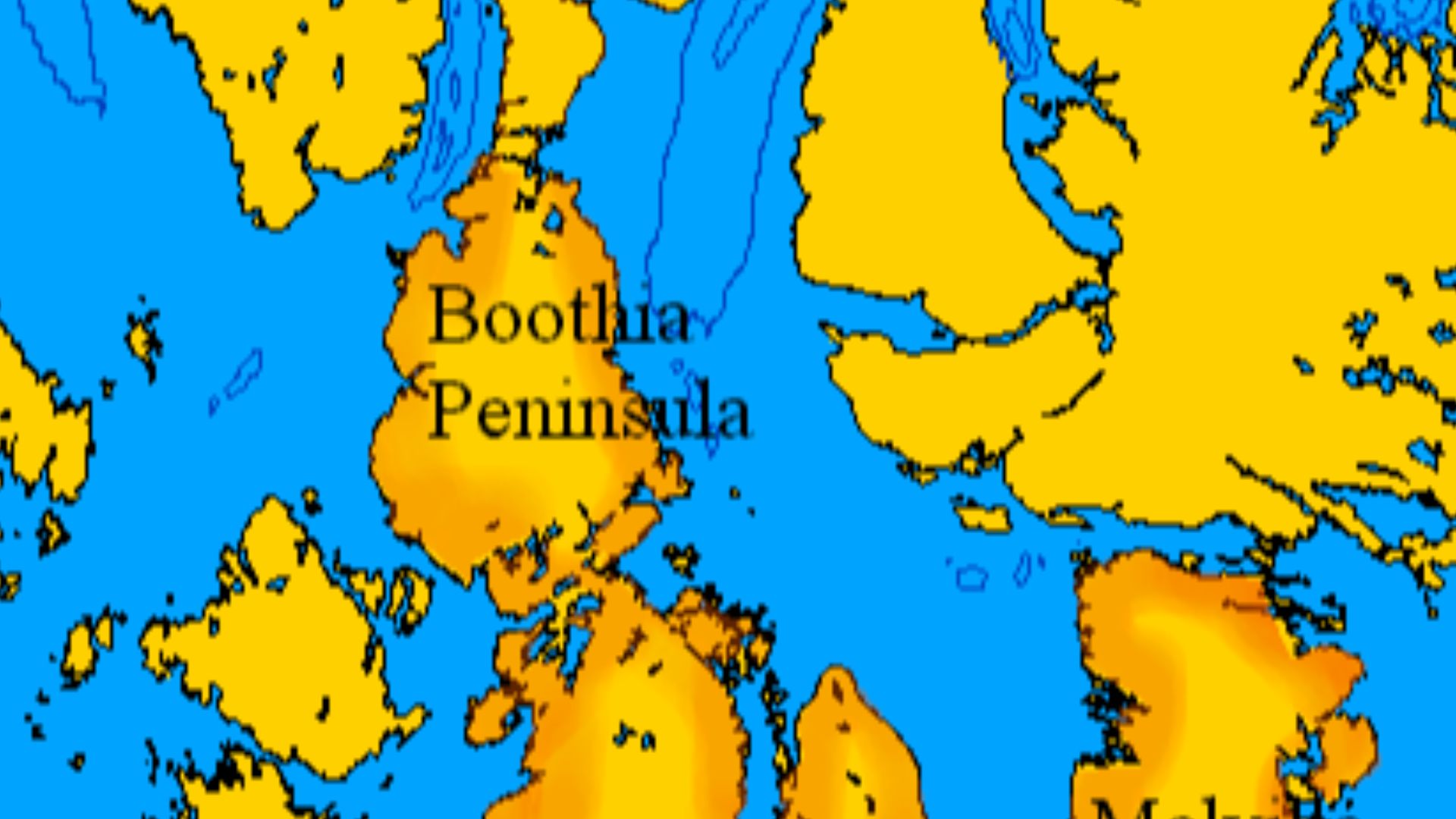

Boothia Peninsula

Prior to the search voyages, there was uncertainty about whether Boothia was an island or a peninsula. The detailed mapping by John Rae (1854) and Francis McClintock (1857–59) during their searches for Franklin’s lost expedition clarified that Boothia was indeed a peninsula.

User:Geo Swan, Wikimedia Commons

User:Geo Swan, Wikimedia Commons

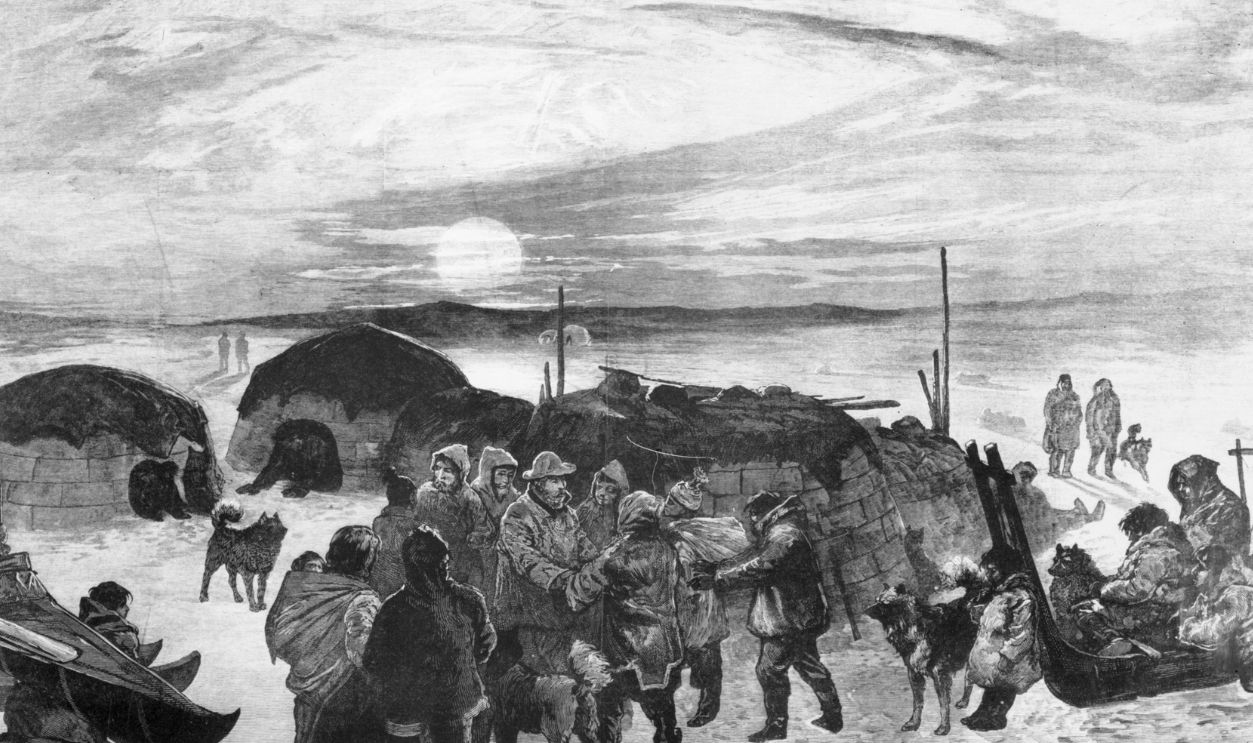

Inuit Knowledge

Coming back, local Inuit people possessed detailed, accurate knowledge about the expedition's fate, including specific information about cannibalism among the starving sailors. They had observed the ships, encountered surviving crew members, and discovered human remains. Their oral testimony provided important insights that European researchers initially dismissed.

Official Declaration

The British Admiralty officially declared all the members dead in service on March 31, 1854, nearly nine years later. This formal declaration ended official hope for survivors and allowed families to receive death benefits. It also marked the end of the Royal Navy's most ambitious project.

Modern Investigation

Owen Beattie initiated a contemporary archaeological investigation of the Franklin Expedition in 1981 when he led the first systematic scientific examination of crew remains on King William Island as part of the Franklin Expedition Forensic Anthropology Project (FEFAP). Beattie and his team retraced the steps of earlier searchers.

Hans van der Maarel, Wikimedia Commons

Hans van der Maarel, Wikimedia Commons

Beechey Excavations

Between 1984 and 1986, the group conducted groundbreaking excavations and autopsies on three crew members buried on Beechey Island. The preserved bodies of John Torrington, John Hartnell, and William Braine provided unprecedented insights into the crew's diet and causes of death.

Gordon Leggett, Wikimedia Commons

Gordon Leggett, Wikimedia Commons

Lead Poisoning Theory

Initial forensic analysis suggested that lead poisoning from poorly soldered tin cans greatly contributed to the expedition's demise, with crew members showing lead levels ten times higher than normal. The hastily manufactured food containers featured thick, sloppy lead soldering that contaminated provisions.

Lead Poisoning Theory (Cont.)

However, subsequent research has questioned whether the tinned food was the sole or primary source of the crew’s lead exposure. Some scientists have proposed that the ships’ desalination systems, which used lead pipes or fittings, may have contributed to the crew’s lead poisoning.

Hi-Res Images of Chemical Elements, Wikimedia Commons

Hi-Res Images of Chemical Elements, Wikimedia Commons

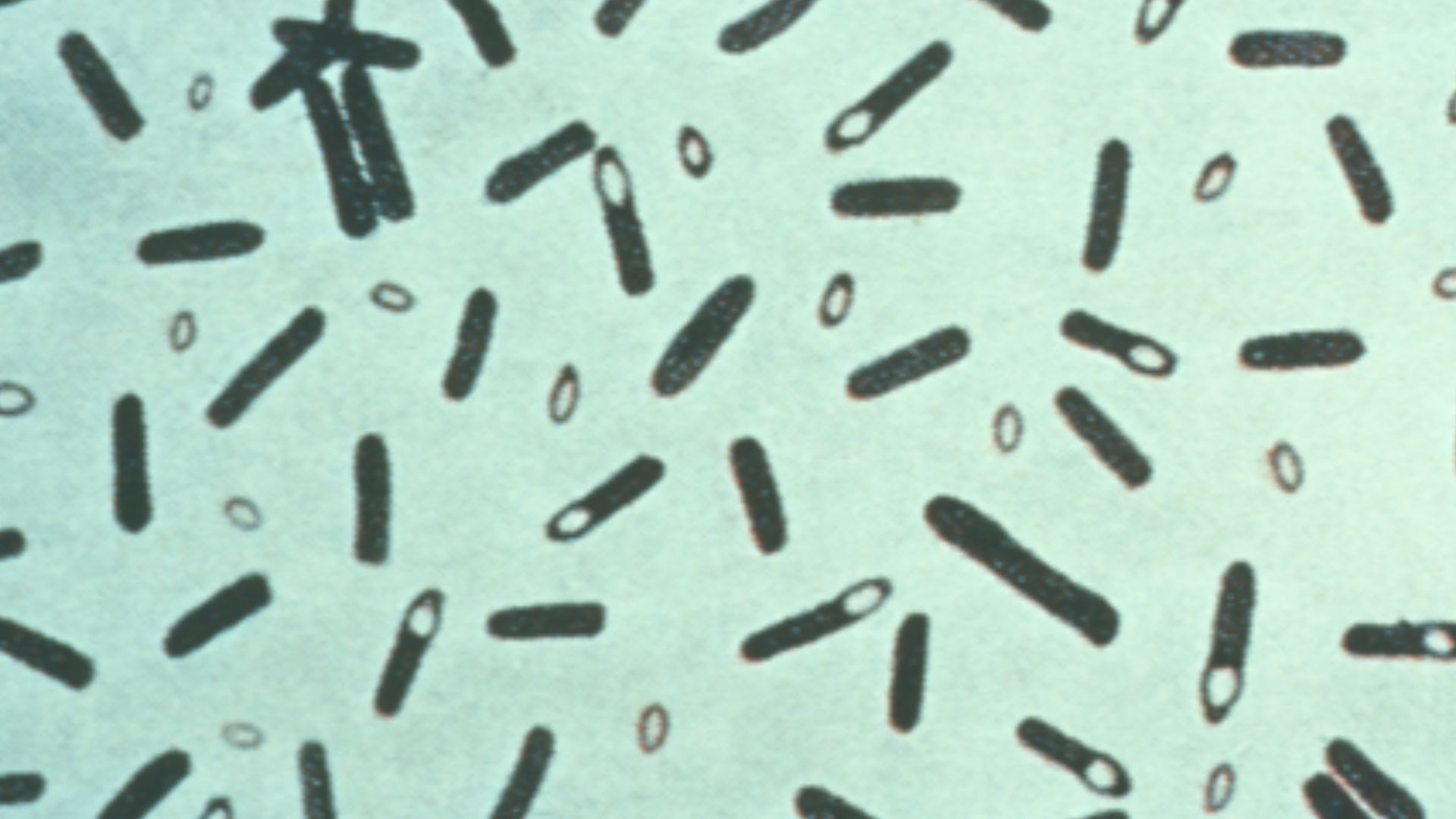

Botulism Discovery

Scientific analysis also showed that animals caught and consumed by the crew contained botulism Type-C, which would have severely compromised their already weakened immune systems. This additional health threat compounded the effects of cold, starvation, scurvy, and other diseases affecting them.

Content Providers: CDC, Wikimedia Commons

Content Providers: CDC, Wikimedia Commons

Ship Recoveries

The discovery of both expedition vessels revolutionized understanding of the Franklin disaster, with HMS Erebus found in 2014 and HMS Terror located in 2016. These preserved wrecks lie in relatively shallow Arctic waters, their wooden hulls protected by cold temperatures and ice.

Ongoing Studies

Contemporary research continues annually at both wreck sites and various land locations, employing all kinds of advanced techniques and sophisticated archaeological methods. Scientists recover artifacts, document ship structures, and search for additional human remains that could be identified through DNA analysis.