A Hilltop Mystery With A Royal Reputation

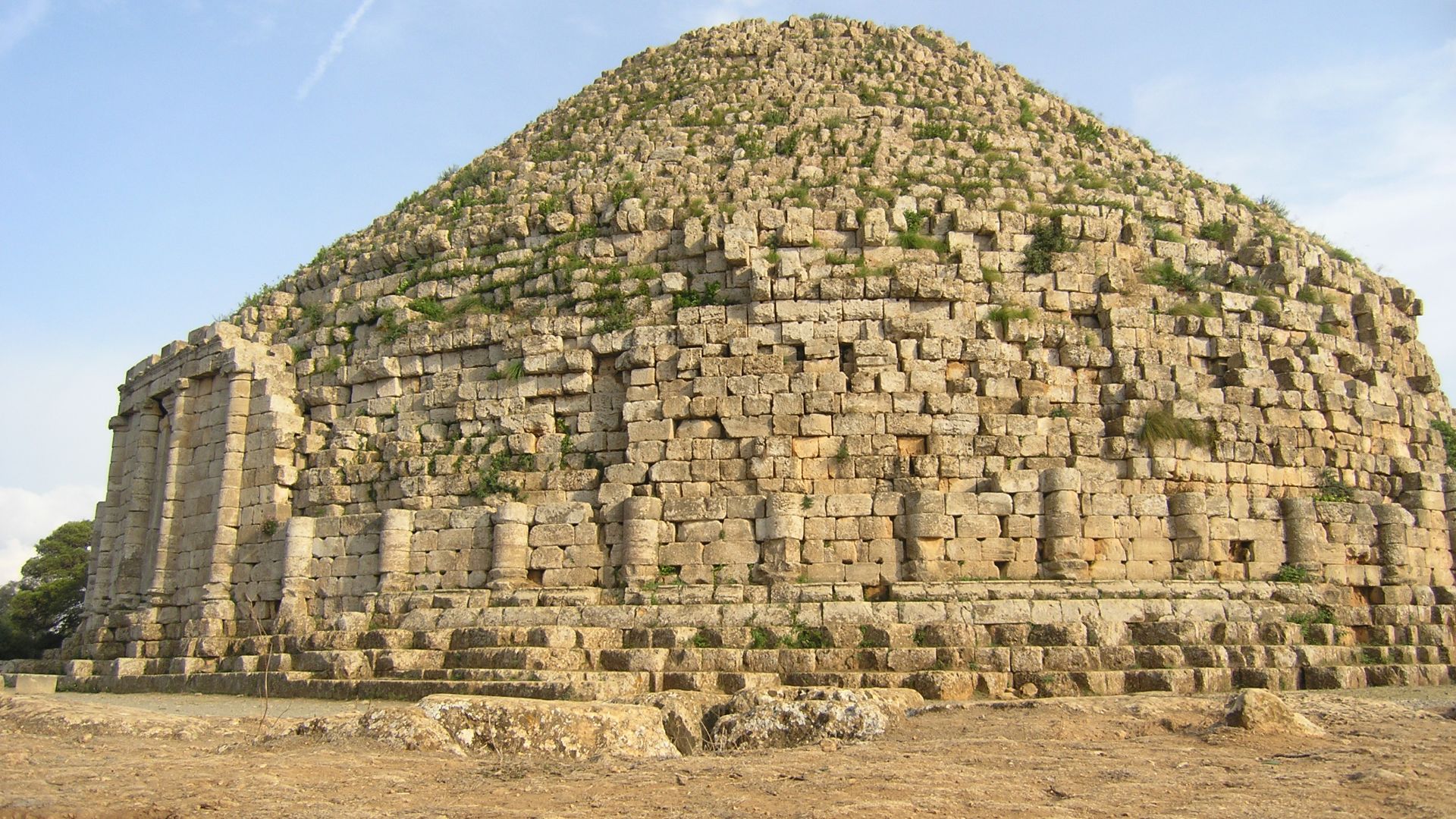

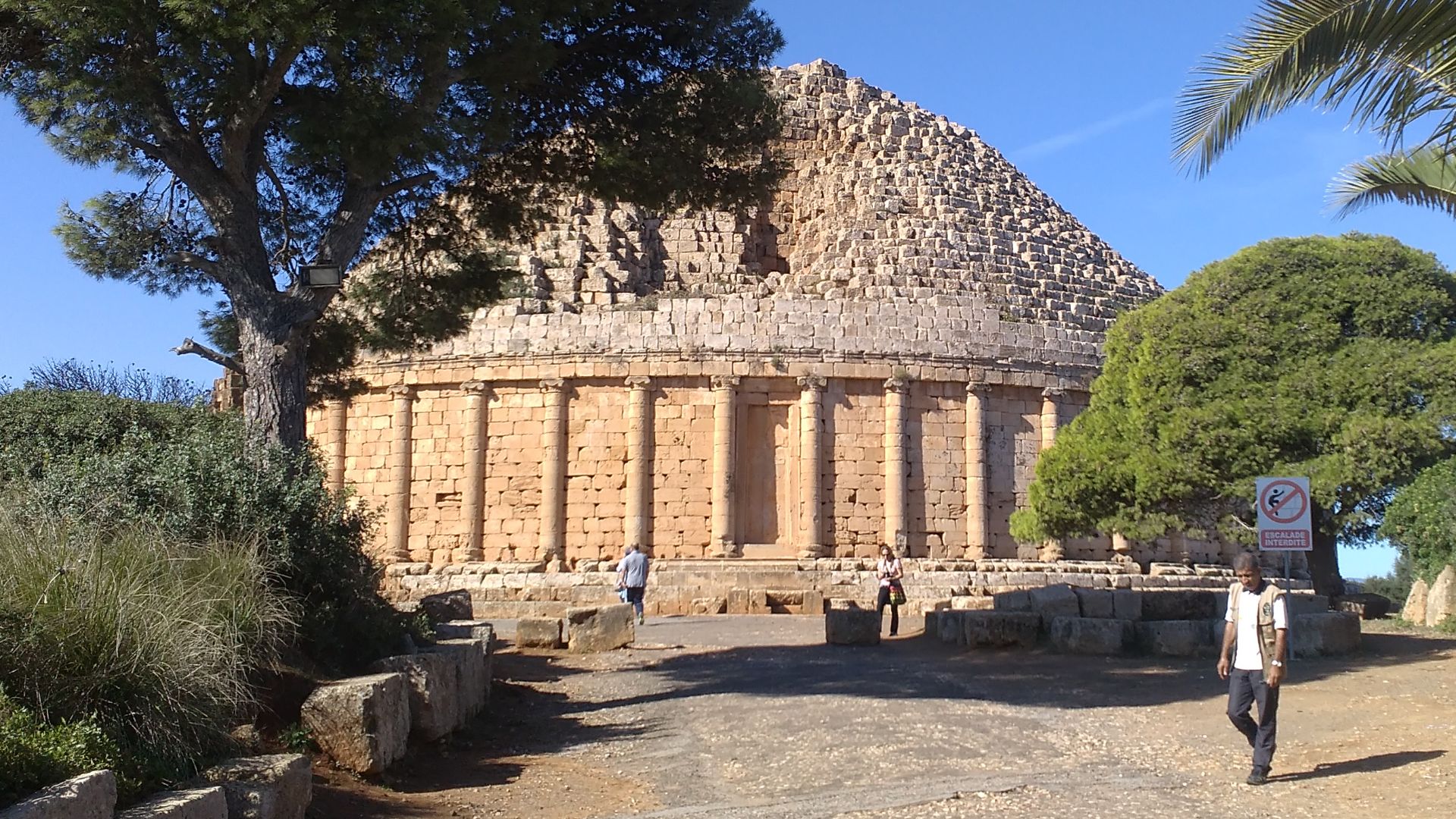

Perched on a low mountain ridge between Algiers and Cherchell, the monument locals call Qabr-er-Rumia (also known as Kbour er-Roumia and, in French, Tombeau de la Chrétienne) is the kind of place that makes you lower your voice without meaning to. It’s a tomb, sure—but it’s also a statement: a 2,000-year-old flex of North African engineering that refuses to be ignored. And while the identity of its occupants can’t be proven, it has long been associated with King Juba II of Mauretania and Queen Cleopatra Selene II—Cleopatra VII and Mark Antony’s daughter—making it one of Algeria’s most intriguing “what if?” sites.

Where Exactly Is Qabr-er-Rumia?

You’ll find it in Tipaza Province, not far from Kolea, on the road corridor that links the coast’s ancient cities. From a distance, it reads like a stony crown dropped onto a hill: a circular mass rising from a squared base, visible across the landscape like a landmark designed for people who didn’t need GPS—just eyes and a sense of awe.

Bernard Gagnon, Wikimedia Commons

Bernard Gagnon, Wikimedia Commons

One Tomb, Many Names, Endless Theories

Names are clues, and this monument has collected them like souvenirs. “Tomb of the Christian Woman” comes from later interpretations of the decorative lines on its false doors, which can resemble a cross shape. Meanwhile, “Qabr-er-Rumia” is often explained through the Arabic rūm/rumi association with Romans/Byzantines—and, by extension in North Africa, “Christians.” The result: a single building wearing layers of language, legend, and misunderstanding.

Fayeqalnatour, Wikimedia Commons

Fayeqalnatour, Wikimedia Commons

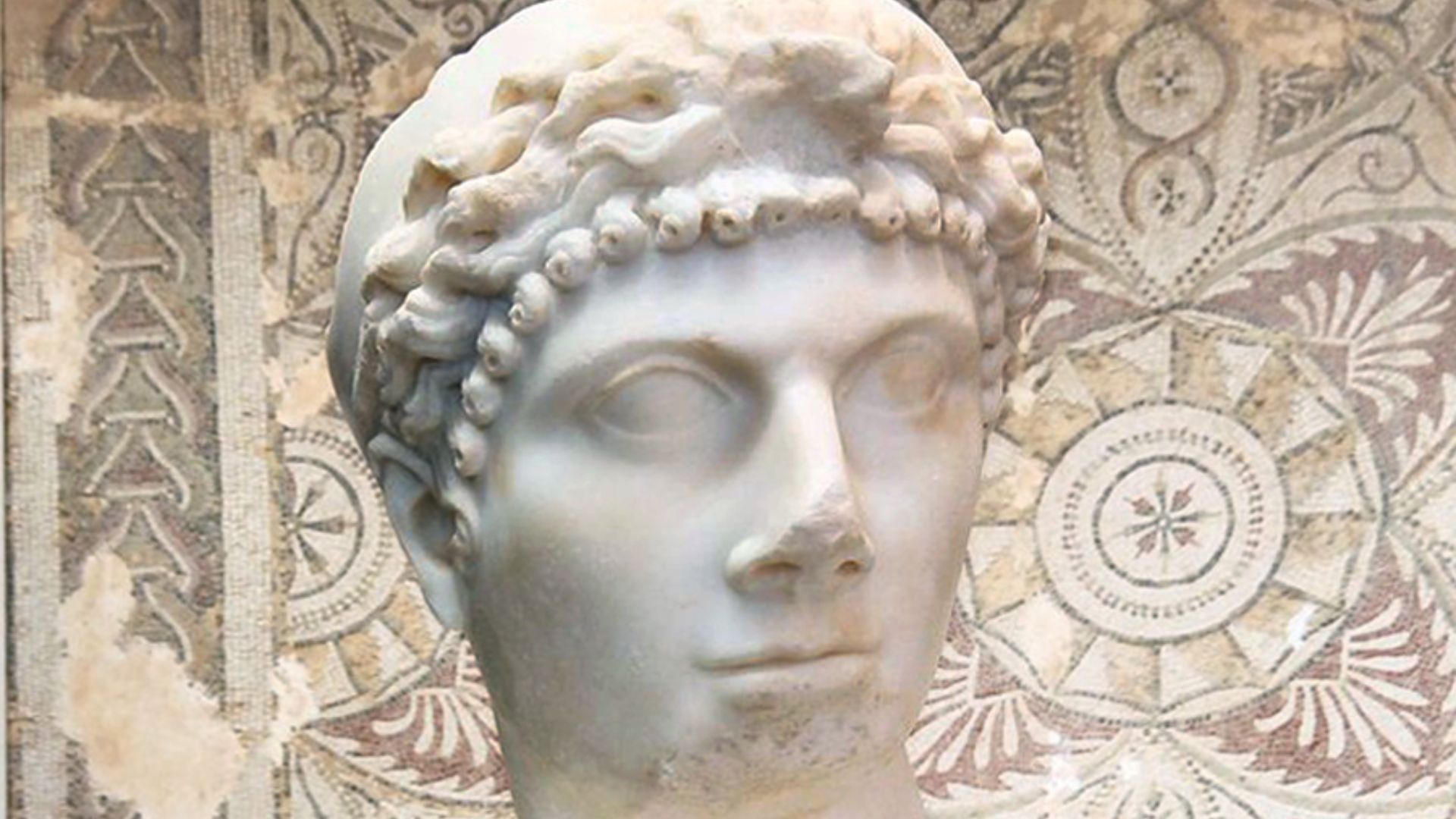

The Royal Candidate: Cleopatra Selene II

Cleopatra Selene II is a historical figure with a dramatic resume: daughter of Egypt’s last Ptolemaic queen, raised under Roman power, and later queen of Mauretania through her marriage to Juba II. The mausoleum is widely believed (but not archaeologically proven via remains) to be connected to this royal couple. That uncertain gap—between tradition and evidence—is exactly where archaeology loves to set up camp.

Hichem algerino, Wikimedia Commons

Hichem algerino, Wikimedia Commons

Meet Juba II, The Scholar-King Builder Type

Juba II wasn’t just a ruler; he was a Roman-educated client king with serious cultural ambition. Under his reign, Mauretania sat at a crossroads of Berber, Punic, and Greco-Roman worlds. A monument like Qabr-er-Rumia fits that blend perfectly: local architectural DNA wearing an international outfit, tailored for eternity.

Bernard Gagnon, Wikimedia Commons

Bernard Gagnon, Wikimedia Commons

A Monument Built Around Presence, Not Just Burial

Ancient tombs often acted like permanent billboards: “Our dynasty is real, our power is stable, and our memory will outlast your argument.” This mausoleum may have been intended not only for one person—or even one couple—but as a dynastic monument for the royal family. Even if the chambers were robbed long ago (or used differently than we assume), the building’s job as a political message still worked.

The Shape That Grabs You First

The overall design is a fascinating hybrid: a square base supporting a circular drum, topped by a conical (or pyramid-like) upper form. That geometry matters. Straight lines stabilize; curves distribute weight; a tapering top helps redirect forces downward. In other words: it’s not just pretty. It’s structural common sense, carved into stone.

Big Stone Energy: The Blockwork

This thing is built from large stone blocks, fitted so tightly that you can almost hear ancient masons muttering, “Measure twice, haul once.” Sources describe the blocks as being held together with metal (lead) cramps—a clever method for reinforcing joints and discouraging movement over time. When you build big, tiny shifts become big problems, so you plan like a pessimist and build like an optimist.

Columns That Once Made It Even Fancier

Around the exterior, the monument originally featured a ring of Ionic columns—a style associated with the Greek world—integrated into a thoroughly North African royal form. Many of the capitals are gone today, but the idea remains: this was a monument meant to be read as cosmopolitan, not provincial.

Bernard Gagnon, Wikimedia Commons

Bernard Gagnon, Wikimedia Commons

The Four “Doors” That Aren’t Doors

At the four cardinal points are monumental false doors—carved entrances that look important while staying stubbornly sealed. False doors are an ancient architectural trick with deep symbolism: they suggest passage between worlds without letting just anyone stroll into the afterlife. They also help balance the exterior design, turning the building into a compass you can walk around.

Why The “Christian Woman” Label Stuck

Those false doors include carved moldings that can resemble a cross-like pattern, which likely fueled the later “Christian” association. But the building itself predates Christianity by centuries. This is one of archaeology’s favorite teachable moments: later viewers interpret earlier monuments using their own cultural vocabulary, and the monument quietly lets them.

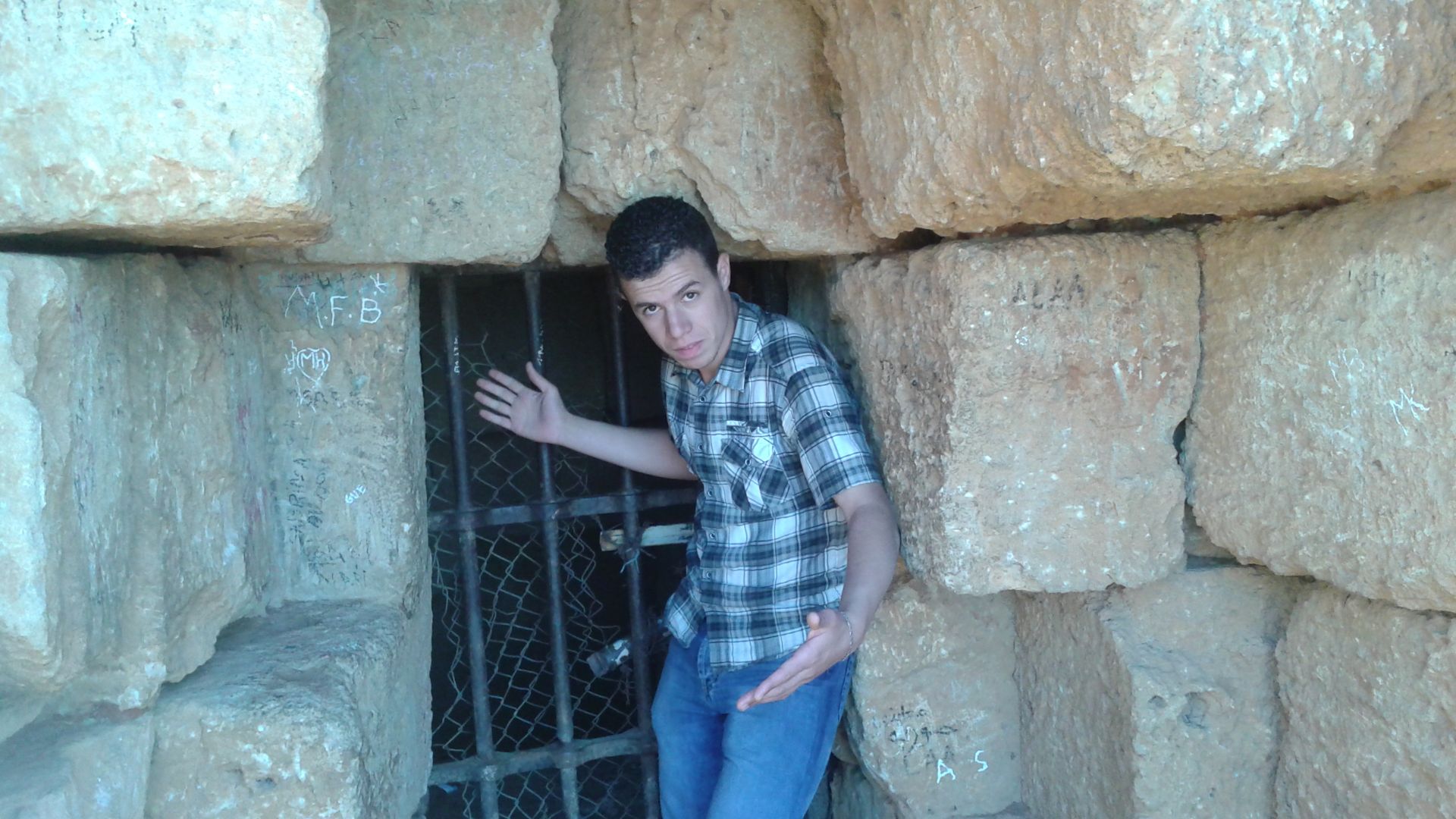

The Inner Maze: A Corridor Built For Secrecy

Inside, the tomb’s engineering becomes downright sneaky. Rather than a simple straight hallway to the burial chambers, accounts describe a long internal passage that leads toward the center. The design makes casual entry difficult and gives the structure a defensive quality—like a bank vault that also happens to be a national landmark.

Rabah rahmouni, Wikimedia Commons

Rabah rahmouni, Wikimedia Commons

Vaulted Chambers: Stone That Learned To Breathe

At the heart are vaulted rooms, a technique that allows stone ceilings to span space by redirecting weight into walls. Vaulting is both elegant and practical: it uses compression—the one thing stone is truly great at. When you see ancient vaults still standing, you’re basically watching physics applaud.

Jamel Matari, Wikimedia Commons

Jamel Matari, Wikimedia Commons

Moving Stone Doors, The Ancient Way

One of the most delightful details reported about the mausoleum is the idea of stone doors that could be manipulated—raised or lowered—using mechanical leverage. Whether every detail of that mechanism survives or not, the broader point holds: North African builders understood that a tomb wasn’t only a sculpture; it was also a controlled interior environment.

Alexandre Garel, Wikimedia Commons

Alexandre Garel, Wikimedia Commons

Building For The Elements: Wind, Sun, Salt

A hilltop site near the Mediterranean means exposure: wind-driven rain, temperature swings, and salty air that chews on surfaces year after year. The fact that the mausoleum still stands—despite centuries of weathering and human interference—is evidence that its builders weren’t guessing. They chose mass, fit, and form with the climate in mind.

DhiaEddineBen10, Wikimedia Commons

DhiaEddineBen10, Wikimedia Commons

A Local Lineage: Earlier Numidian Royal Tombs

Qabr-er-Rumia doesn’t appear out of nowhere. Its design is often discussed alongside earlier North African royal monuments, especially the Medracen (also spelled Medghacen), an older Numidian mausoleum that seems to have provided an architectural template. The message: Mauretania wasn’t borrowing identity—it was extending it.

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

A Global Conversation In Stone

And yet, the monument also “talks” to the wider Mediterranean. Circular royal mausoleums existed elsewhere, and Roman imperial architecture certainly influenced elite tastes. Qabr-er-Rumia feels like a bilingual building: fluent in local tradition, conversational in Greco-Roman style, and perfectly capable of stealing the spotlight.

Carole Raddato, Wikimedia Commons

Carole Raddato, Wikimedia Commons

Engineering Genius Is Sometimes Just Planning Ahead

A building like this requires logistics: quarrying, transport, workforce organization, and precision placement. You don’t casually assemble massive stone blocks on a hill unless you’ve solved the boring problems first—ramps, rollers, schedules, water, food, and muscle management. Engineering isn’t only equations; it’s project management with blisters.

Fayeqalnatour, Wikimedia Commons

Fayeqalnatour, Wikimedia Commons

Anti-Robbery Features… That Humans Eventually Beat

Let’s be honest: tomb robbers are persistent. The mausoleum’s complexity suggests an attempt at protection—hidden routes, heavy doors, long passages. But the absence of confirmed royal remains today hints that, at some point, someone got in. Archaeology often studies not just ancient intentions, but later human behavior—curiosity, greed, devotion, and vandalism.

Legends Love A Monument This Dramatic

Over centuries, people attached stories to the tomb the way vines attach to ruins: Florinda la Cava, Christian princesses, lost royals, cursed treasure. Some legends formed from linguistic misunderstandings; others from the simple fact that a huge mysterious building demands an explanation. When history goes quiet, storytelling shows up with a megaphone.

An Ottoman-Era “Nope” From The Wasps

One famous tale says that in the 16th century, an effort to dismantle the mausoleum was abandoned after swarms of aggressive insects attacked the workers. Whether every detail is perfect or not, it captures something true: this monument has survived multiple historical eras, and more than a few people have tried to bully it into disappearing.

Damage, Target Practice, And The Survival Problem

In later centuries, the mausoleum suffered from deliberate damage—including reports that it was used for target practice during the colonial period. It’s a reminder that preservation isn’t automatic. A monument can survive 2,000 years of weather and still be endangered by a few decades of human choices.

Rabah rahmouni, Wikimedia Commons

Rabah rahmouni, Wikimedia Commons

Seeing The Tomb As A North African Masterpiece

It’s tempting to frame this monument mainly through the Cleopatra Selene connection—because Cleopatra-adjacent history is catnip. But the deeper thrill is architectural: this is North African engineering and royal expression at full volume. Its builders combined geometry, stonecraft, and cultural symbolism into a structure that still dominates its horizon.

Alexandre Garel, Wikimedia Commons

Alexandre Garel, Wikimedia Commons

The Cleopatra Selene Question, Carefully Held

So—does Qabr-er-Rumia “hold Cleopatra Selene”? The responsible answer is: it’s believed to be associated with her and Juba II, but we cannot confirm it from human remains at the site. Archaeology is at its best when it can balance romance with rigor: enjoy the royal theory, but don’t pretend the evidence is stronger than it is.

PericlesofAthens, Wikimedia Commons

PericlesofAthens, Wikimedia Commons

Why It Still Matters Today

This monument matters because it complicates lazy narratives. North Africa wasn’t just receiving architecture from Rome; it was producing ambitious, technically sophisticated monuments of its own—rooted in local tradition and confidently engaged with a wider world. Qabr-er-Rumia is what happens when a region builds for eternity and mostly gets away with it.

What To Look For If You Ever Visit

Walk the perimeter and pay attention to the false doors, the way the circular form sits on its square base, and how the monument reads differently as the light shifts. Notice how it’s positioned to be seen from afar. This is not a tomb trying to hide. It’s a tomb designed to be remembered.

The Real Treasure: A Lesson In Ancient Design

Even emptied chambers can be full of meaning. Qabr-er-Rumia teaches us that ancient builders in Mauretania understood scale, symbolism, and structure well enough to create something that still feels “modern” in its confidence. And whether Cleopatra Selene rests there or not, the engineering genius is undeniably homegrown.

Zouhir Mekdas, Wikimedia Commons

Zouhir Mekdas, Wikimedia Commons

Closing Thoughts From A Very Stubborn Tomb

Qabr-er-Rumia is a reminder that history doesn’t always give us tidy answers—but it does leave spectacular clues. A monument can be simultaneously a royal rumor, a linguistic puzzle, a feat of stone engineering, and a cultural handshake between Africa and the Mediterranean. Two millennia later, it still does its job: it makes you look up, wonder who built it, and feel—just a little—that ancient North Africa knew exactly what it was doing.

You May Also Like:

A Harvard scientist claims he has found the exact location of heaven.