Lost Breeding Knowledge

Most people think that domestication occurred everywhere in the same way. That's wrong. Ancient Americans faced a totally different challenge when trying to tame wild animals. They had to get pretty creative.

Limited Options

Ancient Americans faced a harsh reality that their Eurasian counterparts never experienced—nature had dealt them a poor hand for animal domestication. The Pleistocene extinctions eliminated horses, camels, and giant ground sloths around 10,000 years ago, leaving only small mammals and birds.

Mauricio Anton, Wikimedia Commons

Mauricio Anton, Wikimedia Commons

Dog Arrival

During this time, the first domesticated animals crossed the Bering land bridge alongside Paleo-Indian hunters. These ancient dogs carried unique DNA signatures completely distinct from modern breeds, with their nearest living relatives being Arctic dogs like Alaskan Malamutes and Siberian Huskies.

Guinea Domestication

The Andes witnessed humanity's first major domestication success around 5,000 BC, when indigenous peoples began breeding wild guinea pigs, known as cuy in Quechua. It is said that in present-day Ecuador, Bolivia, and southern Colombia, these people began breeding such small rodents primarily as a food source.

Llama Origins

Between 6000 and 7000 years ago, Andean herders achieved their greatest domestication triumph by converting wild guanacos into reliable pack animals. Genetic analysis reveals multiple independent domestication centers across Peru, Chile, and Argentina, suggesting this innovation occurred simultaneously in different regions.

User:RedRobot, Wikimedia Commons

User:RedRobot, Wikimedia Commons

Alpaca Beginnings

While their cousins became pack animals, alpacas emerged from vicuna ancestors around the same period as specialized fiber producers in Peru's wet puna ecosystem. Selective breeding over 5,000 years created animals producing wool so fine that Inca royalty reserved it exclusively for themselves, calling it “fiber of the gods”.

Philippe Lavoie, Wikimedia Commons

Philippe Lavoie, Wikimedia Commons

Turkey Development

Mesoamerica achieved its vertebrate domestication around 800 BC when central Mexican peoples began breeding wild turkeys initially for ceremonial feathers rather than meat. The process took around 2,000 years, resulting in birds that are quite different from their wild ancestors.

Muscovy Mastery

South American folks accomplished superb waterfowl domestication beginning before 50 CE, particularly with the muscovy duck (Cairina moschata). Unlike mallard-derived ducks, Muscovies were perching ducks adapted to tropical forests. Archaeological sites in Ecuador, Bolivia, and Panama show these birds reached Central America by 750–950 CE.

Luc.T from Buggenhout, Belgie, Wikimedia Commons

Luc.T from Buggenhout, Belgie, Wikimedia Commons

Bee Management

Stingless bee domestication represented one of humanity's most intriguing pre-Columbian achievements. Indigenous peoples across tropical America developed elaborate clay and wooden hives to manage multiple Melipona species for honey and wax production. This practice demanded understanding seasonal cycles, queen management, and colony division.

Cochineal Farming

Mexicans developed the world's most valuable insect domestication by breeding cochineal beetles on prickly pear cacti for the production of intense red dye. This tiny scale insect, smaller than a rice grain, required careful management of both host plants and beetle populations.

Jose Antonio de Alzate y Ramirez (1737 – 1799)., Wikimedia Commons

Jose Antonio de Alzate y Ramirez (1737 – 1799)., Wikimedia Commons

Deer Herding

According to the 16th-century Spanish historian Gomara, in the Apalachicola region of Florida, indigenous peoples practiced a form of deer herding. Gomara noted that “there are very many deer that they raise in the house and they go with shepherds into the pasture, and they return to the corral at night”.

Carl Friedrich Deiker, Wikimedia Commons

Carl Friedrich Deiker, Wikimedia Commons

Geographic Distribution

Animal domestication centers clustered in specific ecological zones across the Americas, with the Andes dominating South American efforts while Mesoamerica led North American innovations. Highland regions between 3,500–5,000 meters elevation proved ideal for camelid breeding. Lowland tropical forests supported Muscovy duck management.

David Adam Kess, Wikimedia Commons

David Adam Kess, Wikimedia Commons

Breeding Techniques

Indigenous Americans developed selective breeding methods without written records, relying instead on oral traditions passed through generations of specialist herders. Inca breeders maintained detailed mental catalogs of lineages, selecting for specific traits like wool fineness in alpacas or load capacity in llamas.

Altitude Adaptation

High-elevation domestication required unique strategies unknown to lowland civilizations, with animals bred specifically for thin-air survival and extreme temperature fluctuations. Llamas and alpacas developed enlarged hearts and increased red blood cell counts to function above 4,000 meters of elevation.

Sacred Roles

Domesticated animals transcended economic utility to become central spiritual figures in pre-Columbian religions, with specific species linked to particular deities and cosmic forces. The jaguar was especially prominent in many pre-Columbian cultures, including the Olmec, Maya, Aztec, and Mexica.

Jaguar

It was viewed as a powerful spiritual animal associated with authority, warfare, fertility, the underworld, and the cosmos. The jaguar was often associated with gods and rulers, symbolizing strength and divine protection. For example, the Maya linked jaguar attributes with underworld gods and royal authority.

Connection To Tezcatlipoca

Additionally, the Aztecs connected jaguars deeply to the God Tezcatlipoca, the shapeshifting God of night and sorcery. This figure is generally depicted as a fearsome earth monster, sometimes with jaguar-like claws, symbolizing strength and the wild power of the earth itself.

Selective Breeding

Pre-Columbian breeders achieved morphological diversity through centuries of careful selection. Guinea pig breeders developed animals three times larger than their wild ancestors, while turkey specialists created birds with reduced flight capabilities and enhanced meat production. Alpaca varieties ranged from ultra-fine fiber producers to hardy mountain workers.

Dietmar Rabich, Wikimedia Commons

Dietmar Rabich, Wikimedia Commons

Geometric Analysis

Domestic guinea pigs (Cavia porcellus) exhibit notable physical changes compared to their wild ancestors, including enlarged skulls and shortened limbs. Geometric morphometric analyses of guinea pig skulls show shape differences, especially a contraction of the braincase and alteration in neurocranial components as part of the domestication process.

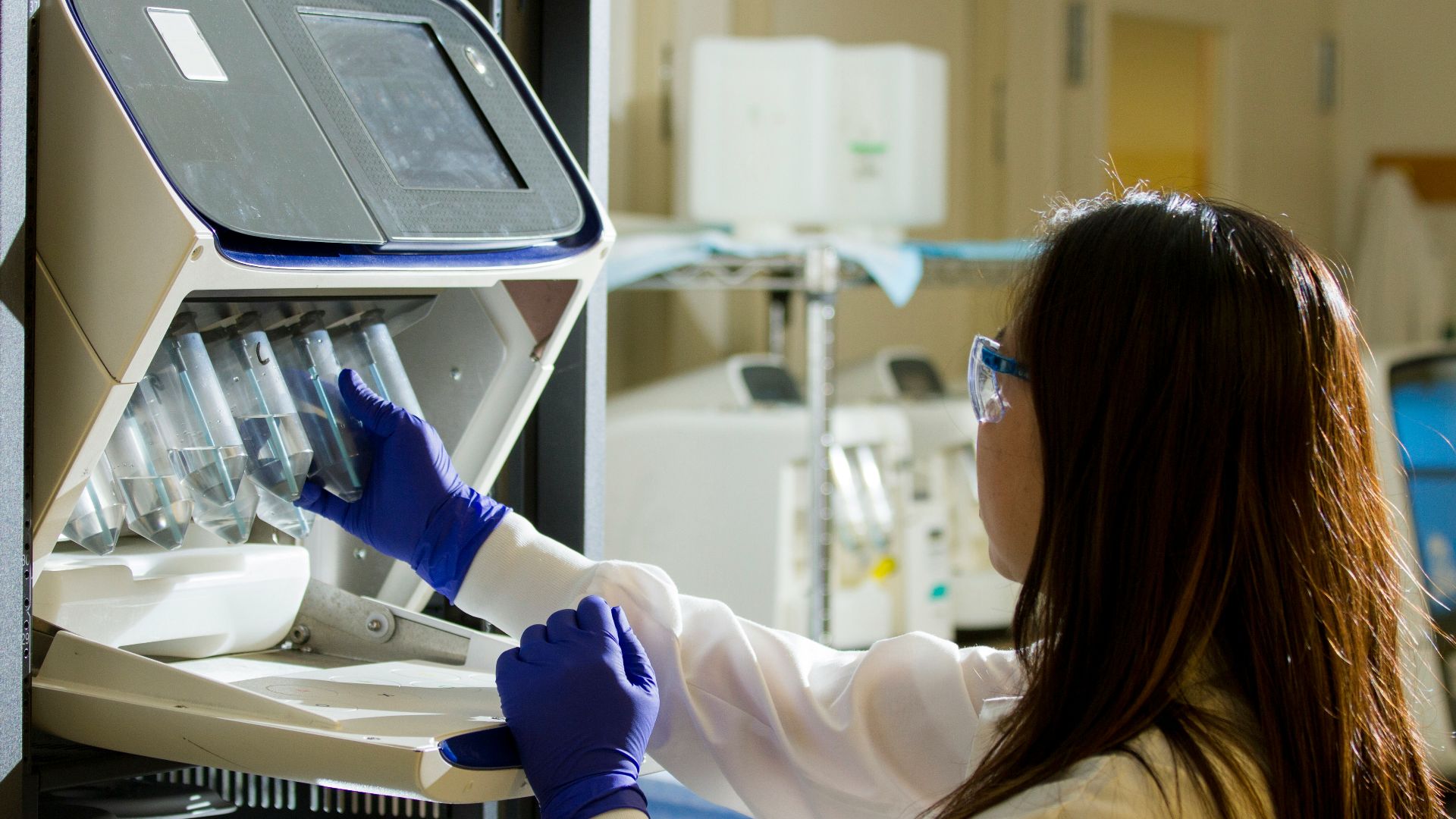

Genetic Analysis

Modern DNA sequencing revolutionized understanding of pre-Columbian domestication by highlighting hidden genetic bottlenecks, founder populations, and breeding program sophistication previously invisible to archaeologists. Mitochondrial analysis shows most domestic guinea pigs descend from single founding events. Turkey studies also identified specific gene variants associated with domestication syndrome traits.

National Cancer Institute, Unsplash

National Cancer Institute, Unsplash

Spanish Impact

Spanish colonists viewed native animals, mainly South American camelids like llamas and alpacas, as inferior to European livestock such as cattle and sheep. This Eurocentric perception led to the widespread mass culling of native camelid herds during and after the conquest.

Hybrid Crisis

Post-conquest chaos triggered massive hybridization between llamas and alpacas as traditional species boundaries collapsed under Spanish colonial mismanagement and population decimation. Genetic studies reveal a 36% introgression in alpaca genomes, compared to only 5% in llamas. Indigenous breeding knowledge transmitted through oral tradition disappeared when communities were destroyed.

Thomas Townsend, Esq., London.[1], Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Townsend, Esq., London.[1], Wikimedia Commons

Population Decline

Within decades of European contact, native Andean camelid populations, particularly alpacas, experienced catastrophic declines. Spanish observers noted a severe decline in alpaca numbers, approaching near extinction. Apparently, survivors were forced into the highest and most inhospitable mountain regions.

Verogonzalezlima, Wikimedia Commons

Verogonzalezlima, Wikimedia Commons

Failed Attempts

Many indigenous domestication efforts never achieved full success despite centuries of experimentation. Scarlet macaw management in Mesoamerica approached domestication, but remained semi-wild. While some animals like llamas, alpacas, guinea pigs, and turkeys were successfully domesticated, other efforts remained limited or incomplete.

Charles J. Sharp, Wikimedia Commons

Charles J. Sharp, Wikimedia Commons

Modern Recovery

It is said that contemporary conservation efforts focus on enhancing a species' adaptability and resilience through careful breeding programs. International export programs introduced these animals to North America, Europe, and Australia, where modern husbandry techniques have improved breeding success rates.

Martin Pettitt from Bury St Edmunds, UK, Wikimedia Commons

Martin Pettitt from Bury St Edmunds, UK, Wikimedia Commons