Underground Mystery

Every old building holds stories, but this Berlin church was keeping a particularly special secret. Folks working on the historic structure never imagined they'd uncover a piece of Prussia's intriguing past.

Renovation Discovery

Construction workers from the Berlin State Office for Monument Protection made an extraordinary discovery during routine renovation works at the historic Schlosskirche Buch on July 8, 2025. The workers uncovered a hidden crypt that had remained sealed for over two centuries.

Konrad Wisendt, Wikimedia Commons

Konrad Wisendt, Wikimedia Commons

Buch Church

The Schlosskirche Buch stands as a remarkable baroque church in the Berlin district of Buch, originally built in the early 18th century as part of the castle complex. This historic church holds special significance as the birthplace of Julie von Voss in 1766.

Olaf Tausch, Wikimedia Commons

Olaf Tausch, Wikimedia Commons

Hidden Crypt

The brick-lined, soil-filled crypt was brought to light during renovation works, hidden beneath accumulated debris and forgotten church floor layers. The rectangular burial chamber appeared to have been deliberately concealed, with no external markings or gravestones to indicate its presence.

Sebastian Wallroth, Wikimedia Commons

Sebastian Wallroth, Wikimedia Commons

Ornate Coffin

Inside the crypt, archaeologists spotted a well-preserved wooden coffin that immediately caught their attention due to its exceptional craftsmanship. The coffin's superior construction and materials suggested it belonged to someone of extraordinary high social standing within 18th-century Prussian society.

Johann Erdmann Hummel, Wikimedia Commons

Johann Erdmann Hummel, Wikimedia Commons

Gilded Decorations

The coffin's surface was adorned with numerous gilded moldings and intricate neoclassical medallions that gleamed. These golden decorative elements featured elaborate baroque and neoclassical motifs typical of late 18th-century aristocratic burial practices. The exceptional quality and extensive use of gold leaf indicated this was no ordinary burial.

Archaeological Team

Dr Sebastian Heber, Head of Archaeology and Monument Preservation at the Berlin State Office for Monument Protection, led the expert team that carefully documented and analyzed the extraordinary find. The archaeological team worked with precision to photograph, measure, and catalog every detail of the burial site.

Christian Wolf (www.c-w-design.de), Wikimedia Commons

Christian Wolf (www.c-w-design.de), Wikimedia Commons

Identity Clues

Multiple pieces of evidence suggested that the coffin's occupant was Julie von Voss, including the crypt's location within the church where she was born and baptized. The singular burial matched historical accounts stating she wished to be buried alone in her childhood church.

Johann Heinrich Schroder, Wikimedia Commons

Johann Heinrich Schroder, Wikimedia Commons

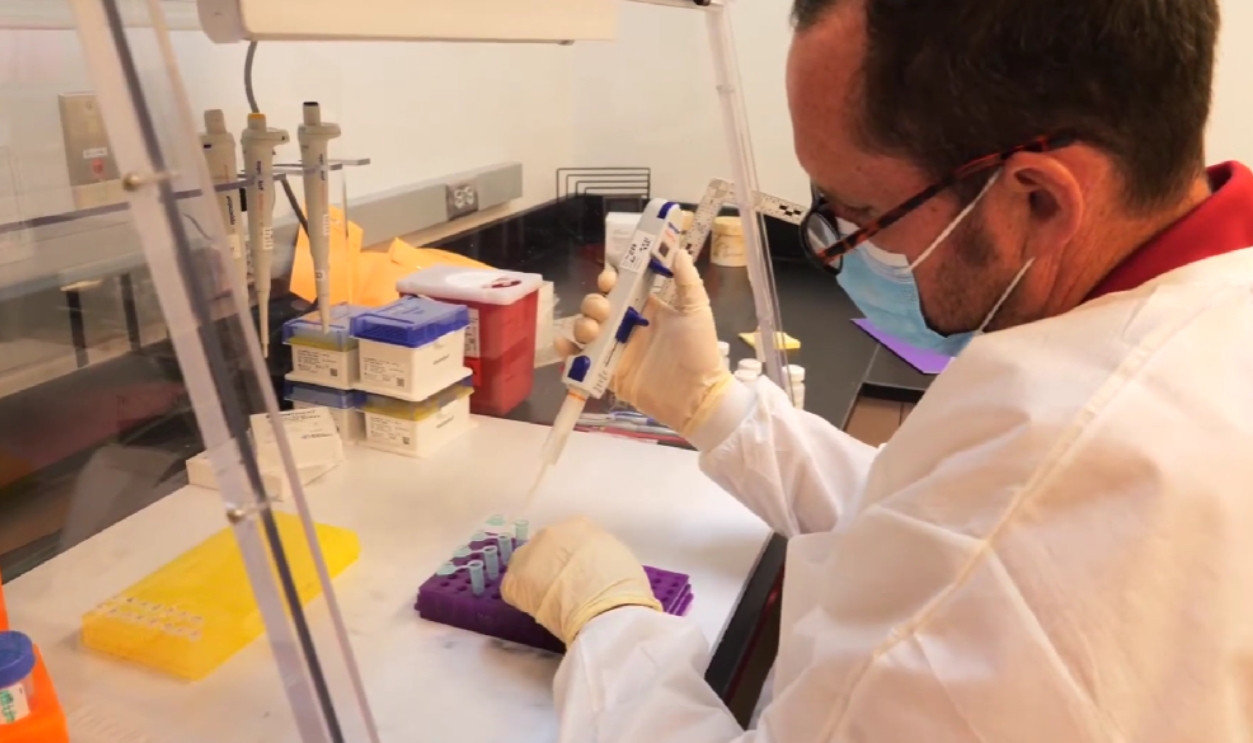

Expert Confirmation

While DNA testing could provide absolute certainty, experts consider the identification highly likely based on overwhelming circumstantial evidence and historical documentation. The archaeological team decided against opening the coffin to preserve the sanctity of the grave and prevent potential damage to the fragile remains inside.

Forensic Science Week: DNA Analysis by Hennepin County Sheriff's Office

Forensic Science Week: DNA Analysis by Hennepin County Sheriff's Office

Prussian Kingdom

During the late 18th century, Prussia was emerging as a major European power under the Hohenzollern dynasty, with Berlin serving as its sophisticated capital city. The kingdom was experiencing significant cultural and political change, moving away from the strict militaristic traditions of Frederick the Great.

Fall Asleep to the ENTIRE Story of The Rise of Prussia by The Quiet Conquest

Fall Asleep to the ENTIRE Story of The Rise of Prussia by The Quiet Conquest

Frederick William

Frederick William II ascended to the Prussian throne in 1786 after the demise of his famous uncle, Frederick the Great, inheriting a powerful but complex kingdom. Unlike his predecessor's austere military focus, Frederick William was known for his love of the arts, music, and elaborate court ceremonies.

Anton Graff, Wikimedia Commons

Anton Graff, Wikimedia Commons

Royal Marriages

In 18th-century Prussia, royal marriages served as essential diplomatic tools, solidifying political alliances and ensuring dynastic succession, rather than prioritizing personal happiness. Frederick William II's marital life personified these complexities, having contracted two official dynastic marriages during his lifetime.

Royal Marriages (Cont.)

His first marriage to Elisabeth Christine of Brunswick ended in bitter divorce after four years of mutual infidelity and public scandal, while his second marriage to Frederica Louisa of Hesse-Darmstadt lasted until his death despite his numerous extramarital relationships and romantic entanglements.

Johann Gottfried Auerbach, Wikimedia Commons

Johann Gottfried Auerbach, Wikimedia Commons

Morganatic Laws

Morganatic marriages represented a unique legal arrangement allowing royalty to wed partners of lower social rank without conferring royal titles or succession rights upon the spouse. These "left-handed marriages" required consent from the reigning monarch's official wife and were recognized as legally valid.

André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri, Wikimedia Commons

André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri, Wikimedia Commons

Birth In 1766

Julie Amalie Elisabeth von Voss was born on July 24, 1766, at Schloss Buch, into a distinguished noble family with deep connections to the Prussian court. Her father, Friedrich Christian von Voss, served as a court official. She was born during the reign of Frederick the Great.

Daniel Berger (1744-1824) und Heinrich Franke (1738-1792), Wikimedia Commons

Daniel Berger (1744-1824) und Heinrich Franke (1738-1792), Wikimedia Commons

Court Appointment

In 1783, at age seventeen, this individual received an appointment as lady-in-waiting to Queen Elisabeth Christine, consort of Frederick the Great. The prestigious position brought her into daily contact with the royal family and exposed her to the sophisticated culture of the Prussian court.

Antoine Pesne, Wikimedia Commons

Antoine Pesne, Wikimedia Commons

Miss Bessy

Her colleagues nicknamed her "Miss Bessy" due to her Anglophile tendencies. This nickname distinguished her as somewhat English in outlook or style amid the Prussian court. However, contemporary accounts considered her neither particularly beautiful nor intellectually brilliant by the court's standards.

Antoine Pesne, Wikimedia Commons

Antoine Pesne, Wikimedia Commons

Royal Attraction

Crown Prince Frederick William became fascinated with her precisely because she initially rejected his romantic advances, a rare experience for the future king. Julie’s resistance intrigued the prince, who was accustomed to easy conquests among court ladies eager for royal favor.

Thomas Dewell Scott, Wikimedia Commons

Thomas Dewell Scott, Wikimedia Commons

Queen's Permission

Count Finckenstein, Julie's relative and political advisor, convinced her to "sacrifice herself for the country" by accepting William's proposal with one critical condition. Julie insisted that Queen Frederica Louisa must formally consent to the morganatic marriage before any ceremony could proceed.

Attributed to Johann Friedrich August Tischbein, Wikimedia Commons

Attributed to Johann Friedrich August Tischbein, Wikimedia Commons

Wedding Ceremony

On April 7, 1787, Julie von Voss married Frederick William II in a small, private ceremony held in the chapel of Charlottenburg Palace in Berlin. The intimate wedding reflected the morganatic nature of their union, with only essential witnesses in a quiet affair.

Hans Christian Genelli (1763-1823), Wikimedia Commons

Hans Christian Genelli (1763-1823), Wikimedia Commons

Countess Ingenheim

Following her marriage, Julie was granted the newly created title of Countess of Ingenheim in November 1787, thereby affording her an appropriate noble rank without royal privileges. This title allowed her to maintain dignity at court while clearly distinguishing her status from that of the official queen.

Friedrich Bock, Wikimedia Commons

Friedrich Bock, Wikimedia Commons

Gustav Adolf

In January 1789, she gave birth to Gustav Adolf, her only child with Frederick William II, fulfilling her primary duty as a royal consort. The birth of this son provided William with another male heir, though Adolf's morganatic status excluded him from direct succession to the throne.

Johann Erdmann Hummel (+ 1852), Wikimedia Commons

Johann Erdmann Hummel (+ 1852), Wikimedia Commons

Tuberculosis Attack

Tragedy struck when the lady contracted pulmonary tuberculosis, known in the 18th century as "consumption" or "white death," one of the era's most feared and incurable diseases. She died on March 25, 1789, at just twenty-two years old, shortly after giving birth to their son.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Burial Request

Julie von Voss had made a specific and unusual final request that reflected her humble nature and deep connection to her birthplace. She explicitly asked not to be interred in the traditional Hohenzollern family mausoleum alongside other royal relatives, preferring instead a solitary burial.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Lost Grave

Over the centuries following Julie's demise in 1789, the exact location of her grave gradually faded from institutional memory and historical records. The absence of any gravestone, combined with changing church renovations and staff turnover, contributed to the complete loss of knowledge about her burial site.

OTFW, Berlin, Wikimedia Commons

OTFW, Berlin, Wikimedia Commons