Baoji in Shaanxi Province has long drawn archaeologists searching for clues about the Western Zhou. Each excavation season confirms its importance, yet recent work has gone further than expected. During new digs, researchers identified a rare system of three concentric city walls arranged as small, middle, and large enclosures. Even more striking, an earlier rammed-earth complex lay beneath them. These findings suggest a settlement that expanded gradually rather than appearing fully formed, where urban planning here followed intention and adaptation.

Not only does the project reveal the modern city of Baoji’s role during the ancient Western Zhou dynasty, but it has revealed how these newly uncovered walls and foundations were built, and explores why their layout matters for understanding early Chinese cities.

The Western Zhou and Baoji’s Role

The Western Zhou dynasty emerged after the fall of the Shang around 1046 BCE, shifting political power westward into what is now Shaanxi. Authority relied heavily on kinship ties, ritual obligation, and carefully placed settlements. Control over space also mattered because it reinforced loyalty and order. Baoji stood at the edge of this political core, which linked the Zhou heartland with surrounding regions.

Archaeological finds had already hinted at Baoji’s status. Bronze vessels with clan inscriptions suggested elite activity, while tombs pointed to long-term occupation by noble families. Palace foundations added another layer, indicating organized governance rather than seasonal use. Scholars often described the city as a ritual center, focused on sacrifice and ancestral ceremonies tied to Zhou legitimacy.

Fortification played a role as well. Western Zhou leaders favored enclosed settlements that defined authority and limited access. Earlier evidence from Baoji showed walls, though they appeared relatively simple. The newly identified structures change that view. The city’s layout suggests deliberate planning, shaped by social order and governance needs. Baoji now appears less peripheral and more experimental, offering insight into how early Zhou rulers shaped cities to mirror political hierarchy.

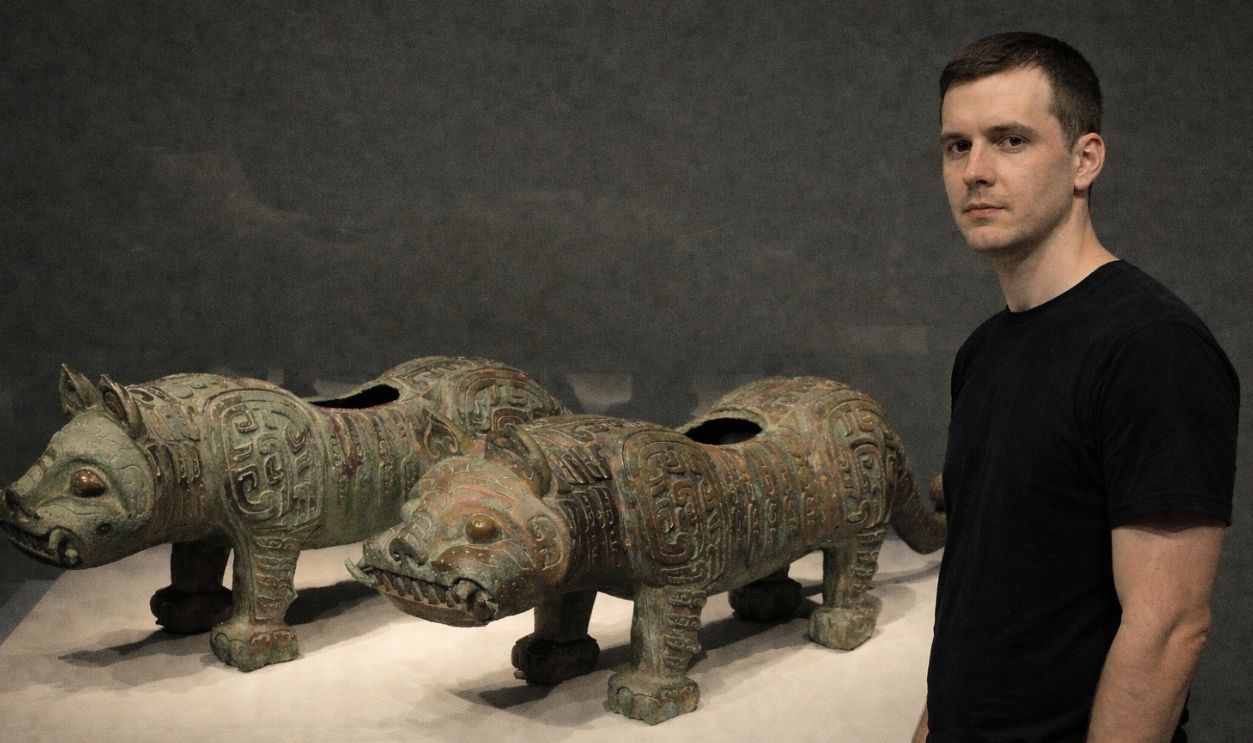

Mary Harrsch, Wikimedia Commons

Mary Harrsch, Wikimedia Commons

Triple City Walls and Rammed Earth Complex

Excavations revealed three distinct walls arranged concentrically, each enclosing a different zone. The smallest wall formed a compact inner area, while the middle and outer walls expanded the city outward. Such a layout suggests careful planning rather than reactive defense. Construction relied on rammed-earth, a method that involved compressing soil in stages to create thick, stable barriers.

Below these walls, archaeologists uncovered an earlier rammed-earth complex. Its presence indicates that Baoji existed before the triple wall system took shape. Growth occurred gradually, with new structures built over older foundations. Urban space here evolved instead of resetting.

Researchers continue to debate how the walls functioned. Inner areas may have housed ritual or elite spaces, while outer zones likely supported administration and daily life. Symbolism also matters. Concentric walls visually express hierarchy, reinforcing who belonged where. Very few Western Zhou sites preserve this level of spatial organization. Baoji, therefore, offers a rare example of how early cities structured authority through architecture rather than written rules.

Significance for Archaeology and Heritage

The Baoji discoveries reshape interpretations of Western Zhou urban life. City walls served more than defensive needs. Spatial order reflected political thinking, social rank, and ritual control. Rammed earth construction further shows confidence in permanence and planning for generations.

These remains also illuminate a broader transition. Early Zhou cities like Baoji bridged Bronze Age traditions and later state systems built around fixed capitals. Understanding that shift helps explain how early Chinese governance stabilized over time. Preservation now presents a challenge. Rammed earth erodes easily, especially when exposed to weather and nearby development.

Protection efforts must balance research access with conservation. What survives today offers more than structural detail. The triple walls and earlier complex reveal how Western Zhou leaders imagined power, community, and space. Baoji stands as physical evidence of those ideas taking shape on the ground.

Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, Wikimedia Commons

Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, Wikimedia Commons