The World Before Denmark Existed

Long before Denmark had shores or islands, a vast stretch of green plains joined Europe to Britain. Mammoths still roamed the north, and humans followed rivers that no longer exist. They hunted, built fires, and lived on land destined to sink beneath the rising sea.

Life In The Stone Age North

Around 6,500 BCE, early humans in the region lived by hunting and gathering wild plants. They built simple shelters from wood and bone, using fire for warmth and light. Communities were small but resourceful, and they learned how to thrive amid harsh weather and shifting coastlines.

Viktor Vasnetsov, Wikimedia Commons

Viktor Vasnetsov, Wikimedia Commons

When The Sea Was Still Land

Before the Baltic Sea formed, a broad stretch of dry ground linked Denmark with Sweden and Britain. Known today as Doggerland, it supported forests and wildlife that sustained early humans. As ice melted and seas rose, that world slowly disappeared.

Andrew Curtis, Wikimedia Commons

Andrew Curtis, Wikimedia Commons

The First Coastal Pioneers

As the sea advanced, people shifted their homes toward the water’s edge. Fishing with bone hooks became common, and flint tools served every purpose from cutting hides to shaping wood. Simple wooden platforms helped them stay dry in places that flooded during seasonal tides.

The Flood That Never Stopped

Rising seas didn’t come in one catastrophic wave—they advanced gradually, year by year. Villages that once stood on dry ground found themselves edging closer to the tide. Families moved inland, leaving behind hearths and wooden walkways

Holger Drachmann, Wikimedia Commons

Holger Drachmann, Wikimedia Commons

The Ghost Villages Of The Baltic

Archaeologists long suspected that parts of Stone Age Denmark lay hidden under the Baltic Sea. During the Mesolithic period, coastal villages dotted the shoreline. As sea levels rose, those sites slipped beneath the water and became buried under centuries of sediment and marine life.

Clues In The Seabed

When marine researchers began surveying Aarhus Bay, they noticed organized lines of stones, flint flakes, and preserved timber pieces. These were not natural formations but clear evidence of human activity. Each clue pointed to a settlement once standing on the ancient coastline before submersion.

Sebastian Nils, Wikimedia Commons

Sebastian Nils, Wikimedia Commons

The Discovery Off Denmark’s Coast

In 2024, archaeologists from Denmark’s National Museum confirmed the presence of an 8,500-year-old site beneath Aarhus Bay. Using sonar scans and underwater excavation, they uncovered remnants of a Mesolithic settlement—one of the oldest known examples of human habitation in northern Europe.

magnetismus from Dresden, Deutschland, Wikimedia Commons

magnetismus from Dresden, Deutschland, Wikimedia Commons

The Study Behind The Sediment

The six-year, €13.2 million (about $15.36 million) EU-funded project involves the National Museum of Denmark, the University of Bradford, and Germany’s Lower Saxony Institute for Historical Coastal Research. The team studies drowned coastlines and excavates submerged sites to understand early sea-level rise and human adaptation.

Richard Mortel from Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, Wikimedia Commons

Richard Mortel from Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, Wikimedia Commons

Project Leadership And Excavation Lead

The underwater excavation in the Bay of Aarhus is headed by Peter Moe Astrup of the Moesgaard Museum in Aarhus. His team also includes researchers from the University of Bradford (UK) and the Lower Saxony Institute for Historical Coastal Research (Germany).

Nanda Sluijsmans from Den Haag, Nederland, Wikimedia Commons

Nanda Sluijsmans from Den Haag, Nederland, Wikimedia Commons

The Lost Settlement Revealed

Excavation teams uncovered traces of homes, workshops, and open spaces. Postholes marked where huts once stood, and scattered flint shards showed signs of toolmaking. The spatial layout suggested a small but organized community that balanced daily labor with shared gathering areas.

The Portable Antiquities Scheme/ The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Portable Antiquities Scheme/ The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

A Village Frozen In Time

Unlike most ancient sites, this one escaped decay. Cold, low-oxygen Baltic waters sealed everything in layers of sand. Organic remains such as wood and bone stayed intact, which preserved an environment that looked much as it did the day it vanished underwater.

Mantas Volungevicius, Wikimedia Commons

Mantas Volungevicius, Wikimedia Commons

The Stone Age Engineers

Archaeologists identified features that showed remarkable technical skill. Timber posts had been arranged in measured rows, and woven barriers likely funneled fish into traps. Such construction revealed early knowledge of design and water management long before the invention of metal tools.

Peter Aikman, Wikimedia Commons

Peter Aikman, Wikimedia Commons

Tools That Tell A Story

Flint knives showed precise knapping, while bone points and antler axes reflected advanced workmanship. These finds reveal how the settlers built, hunted, and worked with natural materials. Each tool added another detail to how the community adapted to a changing coastal world.

Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, Wikimedia Commons

Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, Wikimedia Commons

Daily Life Beneath The Waves

Charcoal fragments, animal bones, and plant residues revealed how families lived. Fish and shellfish dominated their diet, supplemented by berries and forest game. Hearths hinted at warmth and conversation to capture ordinary moments of life before the encroaching sea erased their home.

David.Monniaux, Wikimedia Commons

David.Monniaux, Wikimedia Commons

Diving Into The Past

Underwater archaeology demanded careful precision. Divers in dry suits worked in near-dark conditions, using gentle suction tools to lift silt without breaking artifacts. Each object was photographed, cataloged, and stabilized immediately—preventing centuries of preservation from ending in a moment of exposure.

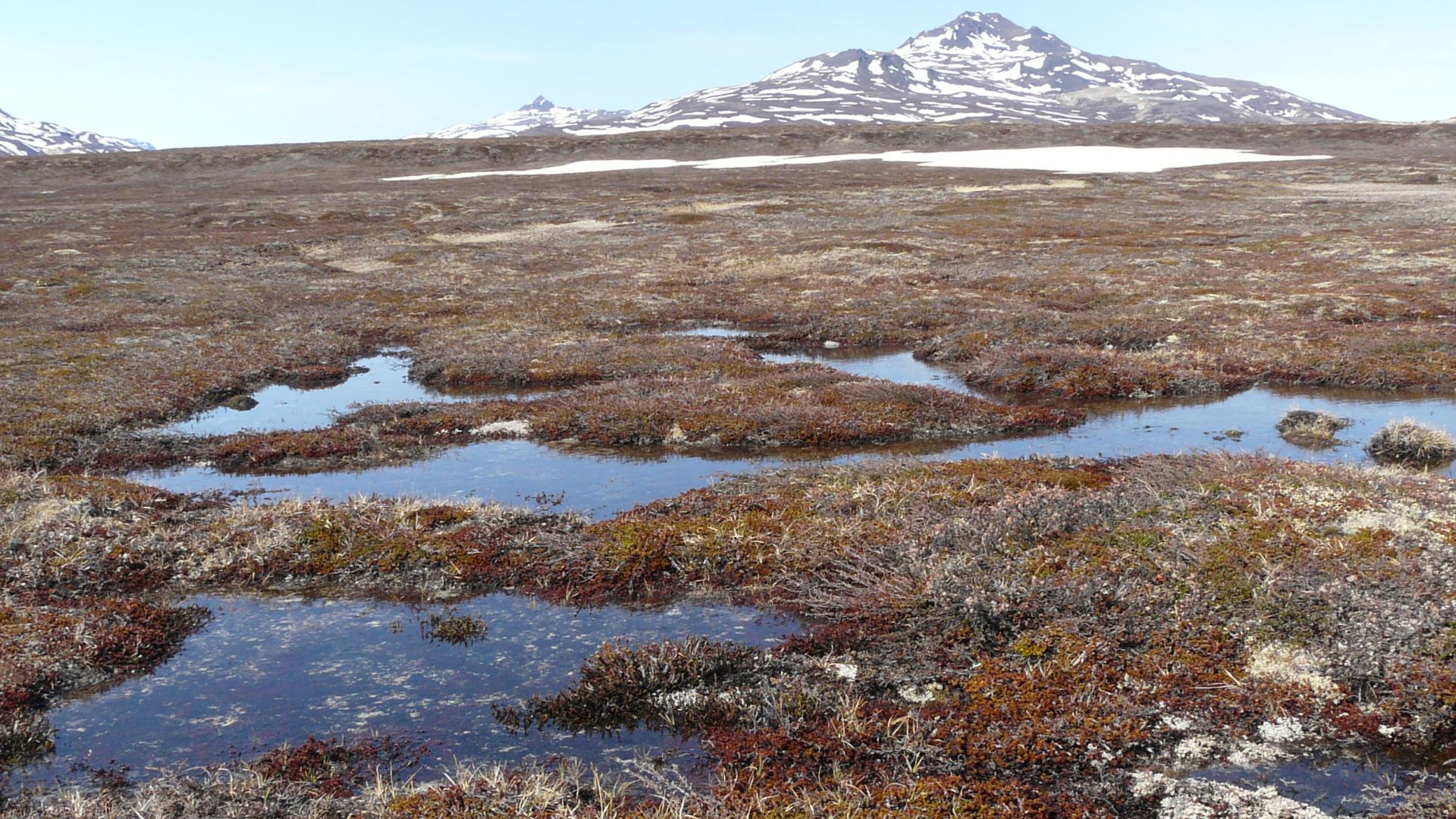

What The Artifacts Reveal About Climate

Sediment samples held pollen and shells that told a broader environmental story. The region had warmed rapidly after the Ice Age, which turned tundra into wetlands. That change explains why the settlement prospered briefly before the advancing Baltic swallowed it completely.

A Glimpse Into Prehistoric Society

The layout of huts, communal fires, and storage pits pointed to cooperation. Tasks were likely divided—some built, others gathered food. Leadership appeared to stem from experience rather than dominance, which suggests one of Europe’s earliest examples of an organized social order.

Lisa Jarvis, Wikimedia Commons

Lisa Jarvis, Wikimedia Commons

Why The Site Matters To Europe

The Danish discovery redefined early European history. It confirmed that complex coastal communities existed long before farming or cities. Together with other submerged sites, it paints a portrait of people who adapted ingeniously to the challenges of post-Ice Age transformation.

Romeo Koitmae, Wikimedia Commons

Romeo Koitmae, Wikimedia Commons

A Puzzle Of The Mesolithic Era

This settlement belongs to the Mesolithic, a period bridging nomadic hunting and settled farming. Evidence from Aarhus Bay fills critical gaps to show how innovation and cooperation paved the way for later agricultural societies that would eventually reshape the continent.

Lessons From The Rising Seas

The gradual drowning of the settlement mirrors modern fears of sea-level rise. Ancient humans faced similar shifts with little technology, yet managed to survive through movement and invention. Their resilience offers insight into how societies can adapt to environmental change today.

Flickr user: Marcus Meissner https://www.flickr.com/photos/marcusmeissner/, Wikimedia Commons

Flickr user: Marcus Meissner https://www.flickr.com/photos/marcusmeissner/, Wikimedia Commons

Collaboration Beneath The Surface

Recovering the site required an alliance of disciplines. Marine scientists, geologists, and archaeologists from Aarhus University and Denmark’s National Museum worked together. Their combined expertise ensured the artifacts were handled correctly and showed that such discoveries rely on cooperation rather than chance.

Villy Fink Isaksen, Wikimedia Commons

Villy Fink Isaksen, Wikimedia Commons

The Baltic’s Silent Archives

Experts now believe the Baltic Sea conceals dozens of similar settlements. Its low salinity and cold waters act as natural preservatives, protecting fragile wood and bone. Each new site promises another chapter in the story of how early Europeans endured dramatic climate shifts.

Dietmar Rabich, Wikimedia Commons

Dietmar Rabich, Wikimedia Commons

Reconstructing The Lost Lands

Digital modeling now helps scientists rebuild the vanished world beneath the sea. Using sonar scans and sediment data, they’ve traced the outlines of rivers and terrain that once surrounded the settlement. The results reveal how early Danes lived in a land that was later claimed by the Baltic.

NOAA's National Ocean Service, Wikimedia Commons

NOAA's National Ocean Service, Wikimedia Commons

A New Chapter In Human History

The site at Aarhus Bay has altered how historians view early Europe. It proves that organized living and skilled construction began long before farming societies appeared. Each object recovered from the seabed adds new evidence of early human innovation and adaptability.

Furya, Flickr, Wikimedia Commons

Furya, Flickr, Wikimedia Commons