Delta's Hidden Pharaoh

Egyptian tombs usually announce their owners loudly. This one stayed silent for 86 years. Then, excavators found an army of ceramic servants arranged in stars, each one carrying the name nobody could find anywhere else.

القناة الأولى المصرية, Wikimedia Commons

القناة الأولى المصرية, Wikimedia Commons

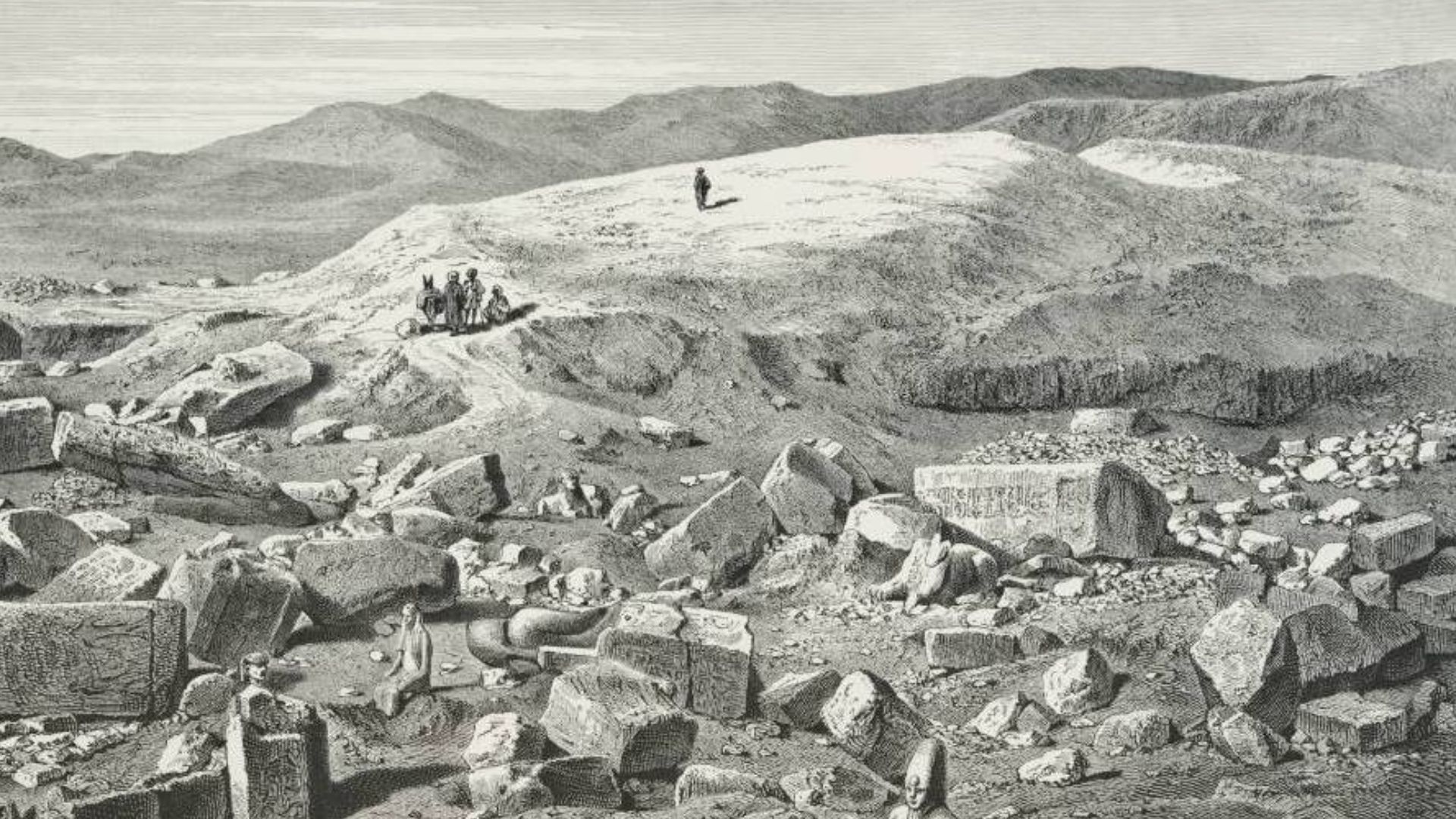

Ancient Tanis

Situated in the Nile Delta northeast of Cairo, this ancient capital thrived during the 21st and 22nd Dynasties. When the New Kingdom collapsed, and the Valley of the Kings was abandoned due to rampant looting, Egyptian royalty needed a new final resting place. Tanis became that sanctuary.

Strassberger, B., Wikimedia Commons

Strassberger, B., Wikimedia Commons

1939 Excavation

The early Egyptian spring of 1939 brought one of archaeology's most spectacular moments. Workers clearing silt from Tanis uncovered something extraordinary: intact royal tombs filled with treasures rivaling Tutankhamun's famous burial. Gold masks gleamed in the excavation lights, silver coffins emerged from the sand, and precious jewelry lay untouched.

Jon Bodsworth, Wikimedia Commons

Jon Bodsworth, Wikimedia Commons

Pierre Montet

French Egyptologist Pierre Montet led the 1939 expedition that changed Egyptian archaeology forever. His meticulous excavation methods uncovered the tomb of Pharaoh Osorkon II, revealing chambers packed with funerary equipment and precious artifacts. Montet's team worked through multiple burial chambers, cataloging thousands of objects.

Jack de Nijs for Anefo, Wikimedia Commons

Jack de Nijs for Anefo, Wikimedia Commons

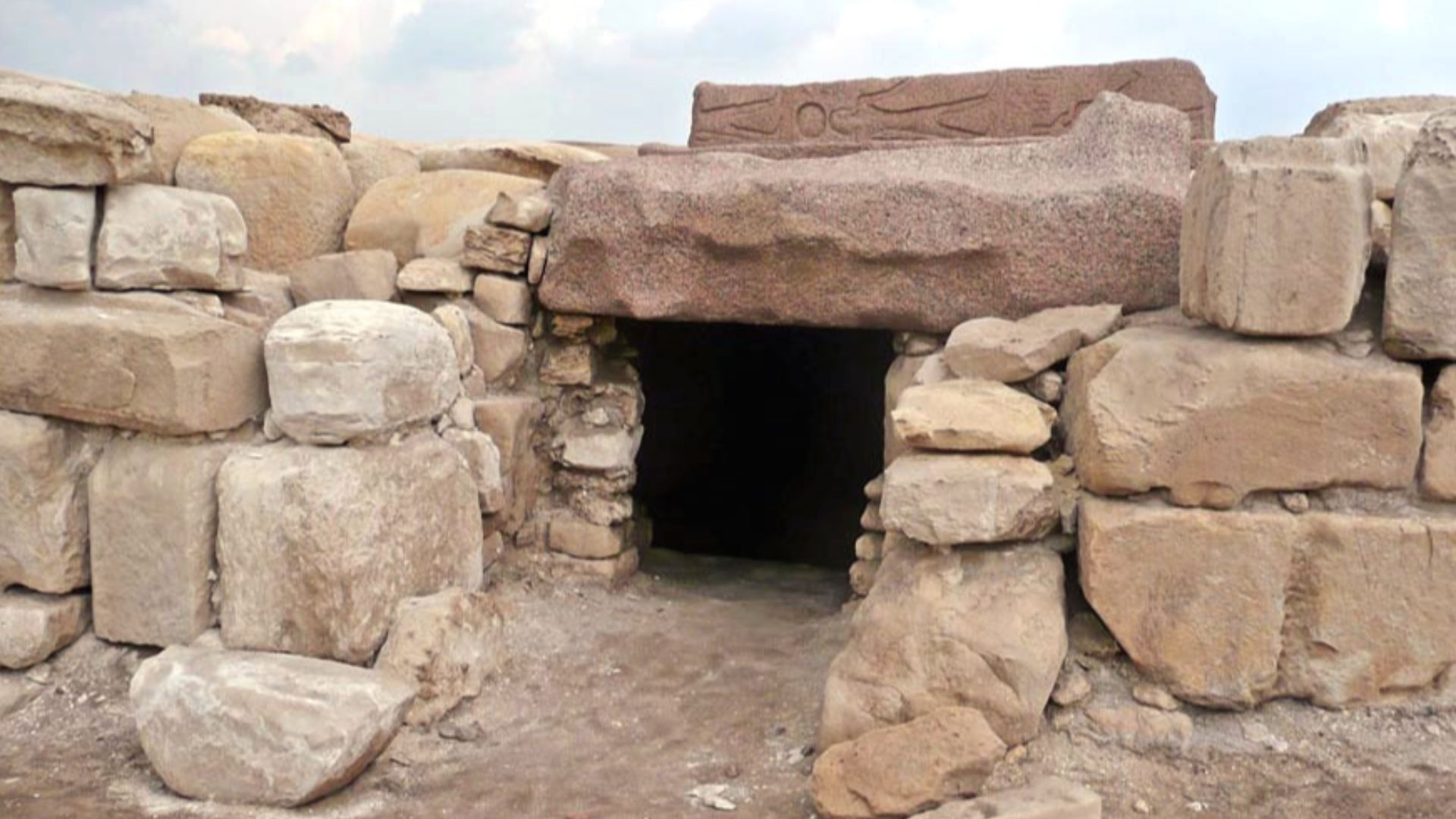

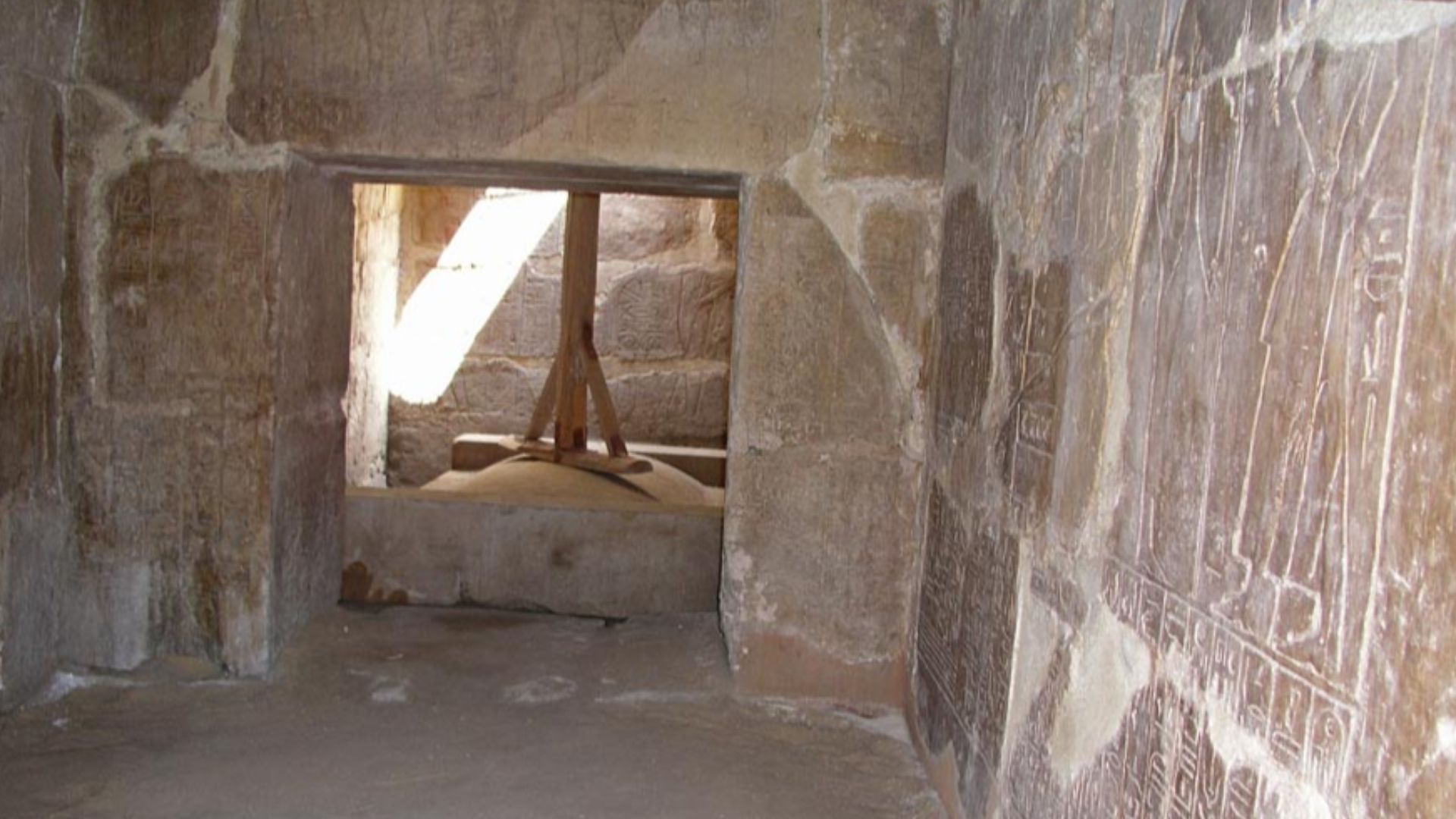

Unopened Sarcophagus

Inside Osorkon II's tomb, excavators encountered a massive granite sarcophagus, potentially measuring around 3–4 meters long, completely devoid of inscriptions. Egyptian royal sarcophagi typically bore elaborate hieroglyphic texts identifying the deceased, listing titles, and invoking protective spells.

Osorkon_IIa.jpg: Jon Bodsworth derivative work: JMCC1 (talk), Wikimedia Commons

Osorkon_IIa.jpg: Jon Bodsworth derivative work: JMCC1 (talk), Wikimedia Commons

86-Year Mystery

Generations of Egyptologists examined, photographed, and debated the anonymous sarcophagus without reaching a consensus. Theories ranged from a secondary wife to a displaced prince or even a protective decoy burial. The chamber underwent periodic inspections and documentation, but advanced technology hadn't yet arrived to unlock ancient mysteries.

Salima Ikram, Wikimedia Commons

Salima Ikram, Wikimedia Commons

French-Egyptian Team

Dr Frederic Payraudeau from Sorbonne University leads the modern French archaeological mission at Tanis, continuing the partnership established in 1929. His team works alongside Egyptian archaeologists from the Supreme Council of Antiquities, combining international expertise with local knowledge.

Ismael zniber, Wikimedia Commons

Ismael zniber, Wikimedia Commons

October Discovery

October 9, 2025, started as routine excavation work in Osorkon II's tomb. The team was cleaning the northern chamber's fourth and final corner, removing centuries of accumulated silt near the mysterious sarcophagus. Then, glimpses of blue-green appeared in the dirt. At first, four small faience figurines emerged together. But there was a lot more than that.

Jon Bodsworth, Wikimedia Commons

Jon Bodsworth, Wikimedia Commons

225 Figurines

The researchers who uncovered the cache knew they'd found something special, but none of them predicted 225 beautifully preserved figurines.

Each small servant figure, crafted from glazed faience ceramic, measured roughly 10 to 15 centimeters tall. The characteristic blue-green glaze represented death, rebirth, and Osiris, lord of the underworld.

Star Arrangement

Archaeologists discovered them arranged in a star formation around the sides of a trapezoidal pit, with horizontal rows lining the bottom. This careful placement reflected ancient Egyptian cosmology, in which stars represented the souls of the deceased as they joined the eternal heavens.

Faience Construction

These weren't crude clay figures but sophisticated ceramic artworks displaying remarkable craftsmanship. Faience—a non-clay ceramic composed of crushed quartz, lime, and natron—was molded, glazed, and fired to build the distinctive blue-green coloration. The manufacturing process required specialized knowledge of materials and firing temperatures.

Royal Cartouche

Hieroglyphic inscriptions covering each figurine's surface told the story archaeologists desperately needed. The carved symbols included a cartouche. Inside that protective border appeared the unmistakable name: Shoshenq III, along with his full royal titulary, including "Usermaatre Setepenamun" and various epithets proclaiming his divine authority.

Juan R. Lazaro, Wikimedia Commons

Juan R. Lazaro, Wikimedia Commons

Shoshenq Identified

The unmarked sarcophagus belonged to Pharaoh Shoshenq III, who ruled Egypt from approximately 825 to 773 BCE. Dr Mohamed Ismail Khaled, Secretary-General of Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities, called this discovery “the most significant find in Tanis's royal tombs since 1946”.

Roland Unger, Wikimedia Commons

Roland Unger, Wikimedia Commons

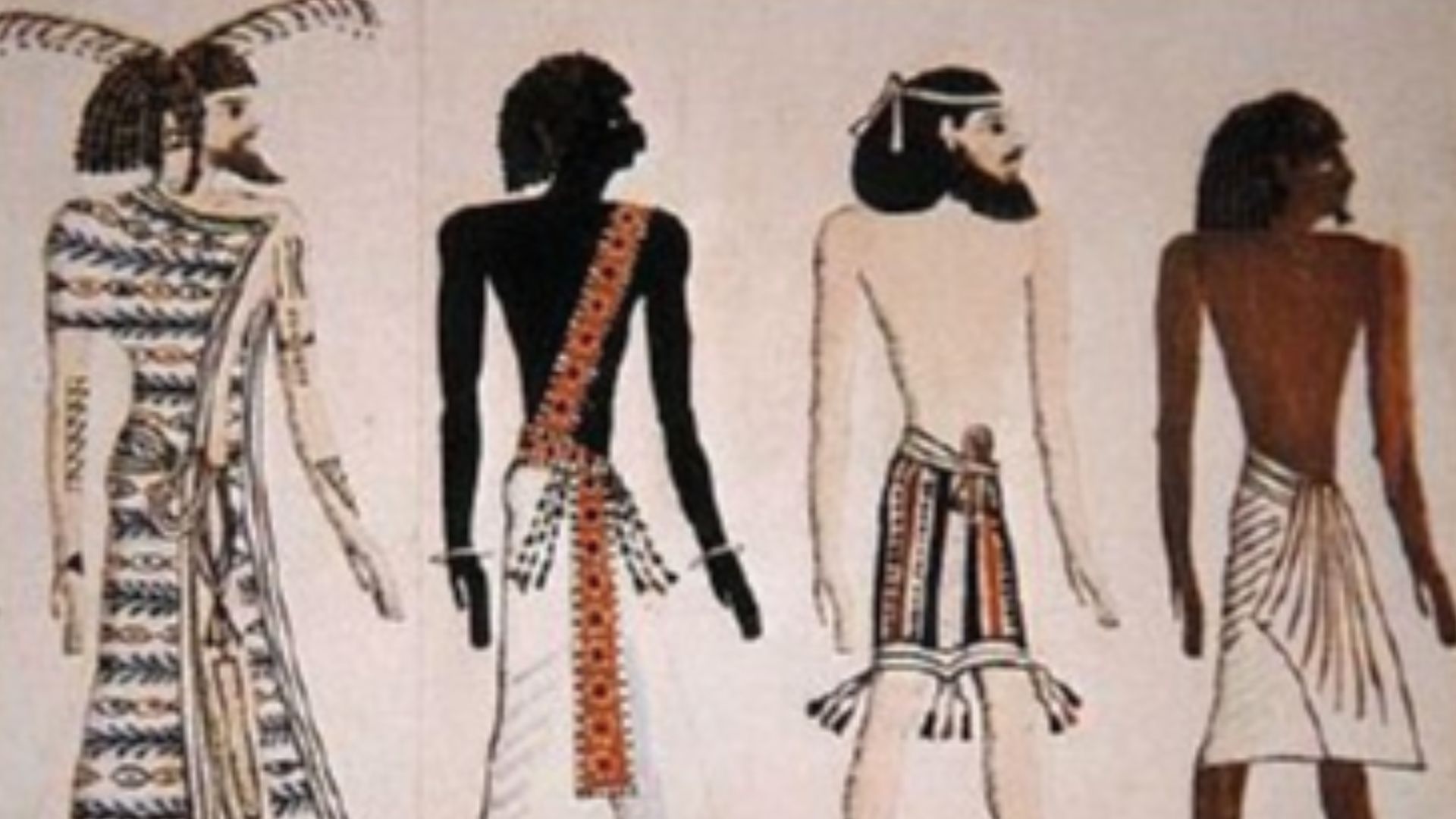

22nd Dynasty

Shoshenq III belonged to Egypt's 22nd Dynasty, also called the Bubastite or Libyan Dynasty because its rulers descended from Meshwesh Libyan chieftains. These weren't foreign conquerors but assimilated families who had settled in Egypt's Delta region generations earlier, serving in military and administrative roles.

Juan R. Lazaro, Wikimedia Commons

Juan R. Lazaro, Wikimedia Commons

Third Intermediate

Egypt's Third Intermediate Period, spanning roughly 1070 to 712 BCE, represented a dramatic change from the glory days of the New Kingdom. The unified empire fragmented into competing power centers: Tanis in Lower Egypt, Thebes in Upper Egypt, and various regional strongholds claiming autonomy.

Vyacheslav Argenberg, Wikimedia Commons

Vyacheslav Argenberg, Wikimedia Commons

Libyan Pharaohs

The Meshwesh Libyans had lived alongside Egyptians since the New Kingdom, originally arriving as immigrants, mercenaries, and prisoners of war. By the late New Kingdom, Libyan military families dominated Egypt's armed forces and held significant administrative positions throughout the Delta.

UnknownUnknown (original) Heinrich Menu von Minutoli (1772–1846) (drawing), Wikimedia Commons

UnknownUnknown (original) Heinrich Menu von Minutoli (1772–1846) (drawing), Wikimedia Commons

Civil War

Shoshenq III's four-decade reign was anything but peaceful. A brutal civil war erupted between Upper and Lower Egypt as rival claimants battled for legitimate pharaonic authority. Multiple individuals simultaneously proclaimed themselves pharaoh, each controlling different regions and resources. Archaeological evidence shows this wasn't a metaphorical conflict.

40-Year Reign

Despite constant political turmoil, Shoshenq III ruled for nearly forty years. It was an impressive feat during such unstable times. He survived through strategic alliances, military strength, and probably shrewd political maneuvering against rival claimants. His longevity outlasted many competitors who died or were defeated.

Osorkon's Tomb

Pharaoh Osorkon II ruled Egypt from approximately 872 to 837 BCE. His limestone tomb at Tanis, discovered by Montet in 1939, served as a gateway to the broader royal necropolis. Ancient robbers had plundered Osorkon's burial, leaving only fragments, ushabti figurines, and his son's quartzite sarcophagus behind.

Roland Unger, Wikimedia Commons

Roland Unger, Wikimedia Commons

Burial Displacement

The discovery raises fascinating questions about why Shoshenq III wasn't buried in his own prepared tomb. One compelling theory involves his successor, Shoshenq IV, who may have appropriated the better tomb for himself, forcing his predecessor's burial into Osorkon II's crowded chambers.

Jon Bodsworth, Wikimedia Commons

Jon Bodsworth, Wikimedia Commons

Shoshenq IV

Archaeological evidence from Shoshenq III's intended tomb complicates the mystery further: artifacts there bear Shoshenq IV's name, suggesting he indeed claimed the superior burial site. Professor Aidan Dodson notes this successor “may have taken over the tomb of Shoshenq III and buried Shoshenq III in the nearby tomb of Osorkon II”.

Jon Bodsworth, Wikimedia Commons

Jon Bodsworth, Wikimedia Commons

Tomb Politics

Ancient Egyptian succession wasn't always smooth, and controlling burial arrangements represented ultimate political authority. The person who performed the final funerary rites and sealed a pharaoh's tomb essentially legitimized their own claim to the throne. It was a public declaration of rightful succession.

unknown artist in Ancient Egypt, Wikimedia Commons

unknown artist in Ancient Egypt, Wikimedia Commons

Afterlife Servants

Egyptian funerary beliefs turned death into an eternal continuation of earthly life in the paradise called the Field of Reeds. However, this afterlife required agricultural labor—plowing, sowing, harvesting—just like mortal existence. Wealthy Egyptians solved this problem by commissioning ushabti figurines inscribed with Chapter Six from the Book of the Dead.

Marco Chemello (WMIT), Wikimedia Commons

Marco Chemello (WMIT), Wikimedia Commons

Conservation Plans

The discovery occurred during preparatory work for an ambitious preservation project addressing Tanis's deteriorating monuments. The French-Egyptian team plans to install protective coverings over the entire tomb complex, shielding vulnerable structures from rain, wind-blown sand, and temperature fluctuations.

Roland Unger, Wikimedia Commons

Roland Unger, Wikimedia Commons

Ongoing Research

Payraudeau's team continues analyzing newly discovered inscriptions within the northern chamber that promise additional insights into Third Intermediate Period burial practices. These texts may clarify whether Shoshenq III's physical remains are in the sarcophagus or whether only his funerary equipment was stored there for safekeeping.

James Byrum from Nowhere, Wikimedia Commons

James Byrum from Nowhere, Wikimedia Commons