Fingers Of Blame…

Rome’s demise took centuries to complete—and six volumes to explain in the Decline And Fall Of The Roman Empire. Edward Gibbon, an 18th-century English historian, pinned part of the blame on Christianity, but modern historians see more-likely suspects, so let’s investigate!

Long Live The Republic!

Augustus became the Roman Empire’s first leader when the Roman Republic, ill for some time, passed around 27 BCE. The ultimate cause included Julius Caesar’s assassination and Antony and Cleopatra’s uprising. And now Rome’s first emperor offered stability.

Vatican Museums, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Vatican Museums, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Road To A New Future

Through his four decades of power, Augustus would take over Egypt and complete Rome’s conquest of Iberia. He’d create an extensive road system on which Roman legions and couriers could speed. And he fixed an erratic taxation system, vastly improving Rome’s finances.

Olaf Tausch, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Olaf Tausch, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Germania Fights Back

But he also sowed the seeds of discontent. His armies took over Gaul, but made the mistake of crossing the Rhine in 13 BCE. Augustus eventually won enough land to add “Germania” to his empire, but in 9 CE, an ambush massacring three Roman legions prompted a quick retreat.

Ollier, Edmund, Wikimedia Commons

Ollier, Edmund, Wikimedia Commons

Roman Subterfuge

But Rome kept up pressure by playing one Germanic tribe against the other and meddling in who got selected as tribal leaders. There were brief skirmishes and revolts, but things stayed fairly quiet until 168, when “barbarians” invaded northern Italy in a 12-year conflict.

Évariste Vital Luminais, Wikimedia Commons

Évariste Vital Luminais, Wikimedia Commons

A Reluctant Welcome

To get some peace, Rome agreed to let some of the invaders settle on Roman land, even if it destabilized some areas. Then Goths invaded Rome’s Black Sea territory in 238, followed by a major victory over the Romans at Philippopolis in present-day Bulgaria in the year 250.

rivigan, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

rivigan, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

A Bigger Danger

Things seemed to quiet down a bit, but then came a couple of twists. Rome started relying on Germanic forces to defend itself against Germanic forces, all the while paying some tribes to beat up other tribes. Then the Huns showed up in 375, pushing more Goths into the Empire.

![]() After Eduard Bendemann, Wikimedia Commons

After Eduard Bendemann, Wikimedia Commons

Gothic Displeasure

Rome granted some of the fleeing Goths asylum, but treated them badly, forcing some parents to give up their children to slavery in exchange for dog meat. The Visigoths were getting pretty restless over Roman nastiness, corruption, and bureaucracy, so Emperor Valens showed up.

Papageizichta, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Papageizichta, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Roman Vulnerability

In present-day northeastern Greece, Valens led his Roman legions to their doom—and lost his own life—at the Battle of Adrianople in 378. After various revolts and battles, some Visigoths were settled in Gaul in exchange for becoming allies, and Rome no longer looked so invincible.

C. Murer, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

C. Murer, CC BY 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

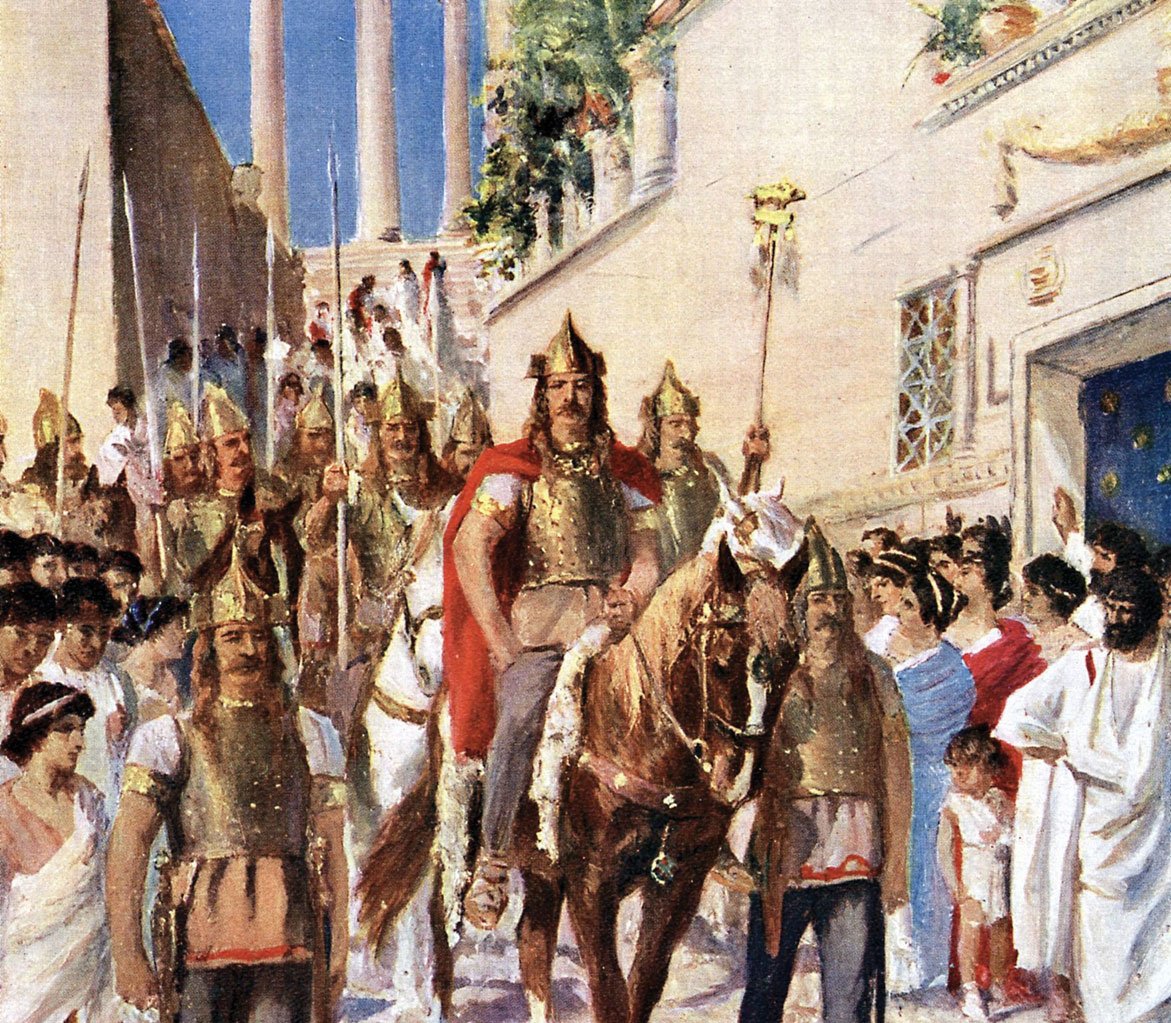

When In Rome…

Meanwhile, the Huns kept advancing, pushing more Goths onto Roman territory. In turn, the Visigoths’ first king, Alaric, sacked Rome in 410, then fled to Gaul. As a bad century for Romans wore on, they also lost Carthage to the Vandals in 430, bringing more Mediterranean piracy.

Allan Stewart, Wikimedia Commons

Allan Stewart, Wikimedia Commons

Not A Good Move

Meanwhile, Roman Emperor Valentinian III personally assassinated his brilliant general Aetius, who had helped defeat the Huns at the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains in Gaul in 451 CE. After Attila’s passing in 453, the weakened Huns gradually dissipated. Aetius had proven his worth.

Louvre Museum, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Louvre Museum, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Ferocious Vandalism

But with Aetius out of the picture and Huns becoming less of a concern, Vandals were on the ascendant. In 455, it was the Vandals who were sacking Rome—and with such determination and ferocity that the English terms vandal and vandalism would enter our modern lexicon.

Lordkinbote, Wikimedia Commons

Lordkinbote, Wikimedia Commons

The Last Emperor

Though there are different falls one can point to, it seems the most dramatic of moments was soon approaching. In 476, Odoacer, a Germanic commander for the Roman Empire rebelled and overthrew the Western Empire’s last emperor, a boy named Romulus Augustus.

B. Moerlins, Wikimedia Commons

B. Moerlins, Wikimedia Commons

Making It Obvious

The “barbarians” had been wielding effective power for decades, so Odoacer’s move was just making it plain that formalities of the past didn’t reflect current reality. The despised and belittled Germanic peoples, at best seen as second-class mercenaries, were now evidently in charge.

Bradley, Henry, Wikimedia Commons

Bradley, Henry, Wikimedia Commons

Taxing His Patience

And then there was the money. Despite there being an Emperor in the West and in the East, there was just one treasury. Odoacer was likely fed up with his side’s taxes going into a common pot from which little returned to the West. Now Odoacer could spend the very money he collected.

Ludwig Thiersch, Wikimedia Commons

Ludwig Thiersch, Wikimedia Commons

Barbarian Vs Barbarian

However, Byzantine leaders in Constantinople were incensed and wanted Odoacer removed from the map. They dispatched Theodoric, another barbarian, to eliminate the usurper. Theodoric complied and defeated Odoacer in 493—but Theodoric turned out no more willing to turn over local taxes than his victim had been.

Tteske, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Tteske, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

A Last Hurrah

Instead, this Theodoric spent money on revitalizing infrastructure and culture as Rome enjoyed a brief twilight resurgence of its former glory—though executing the philosopher Boethius has probably not done his reputation much good. Nonetheless, Theodoric had his moments.

José Luiz, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

José Luiz, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Empire Struts Back

The fall of the Roman Empire corresponded with the reign of Odoacer, so it was over, at least in the west, by 476. Curiously, in 800 CE, the Frankish king Charlemagne proclaimed himself head of the Holy Roman Empire—which, as French philosopher Voltaire quipped centuries later, wasn’t very holy, Roman, or much of an empire.

Florian B. Gutsch, CC BY-SA 4., Wikimedia Commons

Florian B. Gutsch, CC BY-SA 4., Wikimedia Commons

Digging Deeper

While we could say the Roman Empire fell because it kept losing land, is that a good explanation—or just a description of what happened? And if that’s kind of like saying Rome fell because it lost, then we have to ask: Why did it keep losing? And what’s this about two Emperors and two Empires? How did that happen?

![]() Ivan Dmitrievich Sytin, Picryl

Ivan Dmitrievich Sytin, Picryl

Division Of Labor

The thing about empires is that they can be pretty big and hard to manage. So the Emperor Aurelian had barely reassembled the squabbling pieces of the Empire in 274 when a successor, Diocletian, formally split the empire into Western and Eastern divisions in 293.

Giovanni Dall'Orto., Wikimedia Commons

Giovanni Dall'Orto., Wikimedia Commons

Conflicting Motives

But a relatively weak Western Empire had trouble on two fronts. First, it had to control existing populations who resented occupation. Then it had to deal with waves of refugees coming in from the east, pushed westward by the advancing Huns or others that the Empire had previously pushed forward.

Bernard Gagnon, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Bernard Gagnon, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

No PR Campaign

Interestingly, victors usually get to write the history books, but the Huns couldn’t be bothered. Starting off in Mongolia, they galloped their way to Europe, with a fearsome reputation for inflicting great bloodshed. But Attila and company didn’t care to justify themselves.

Ulpiano Checa, Wikimedia Commons

Ulpiano Checa, Wikimedia Commons

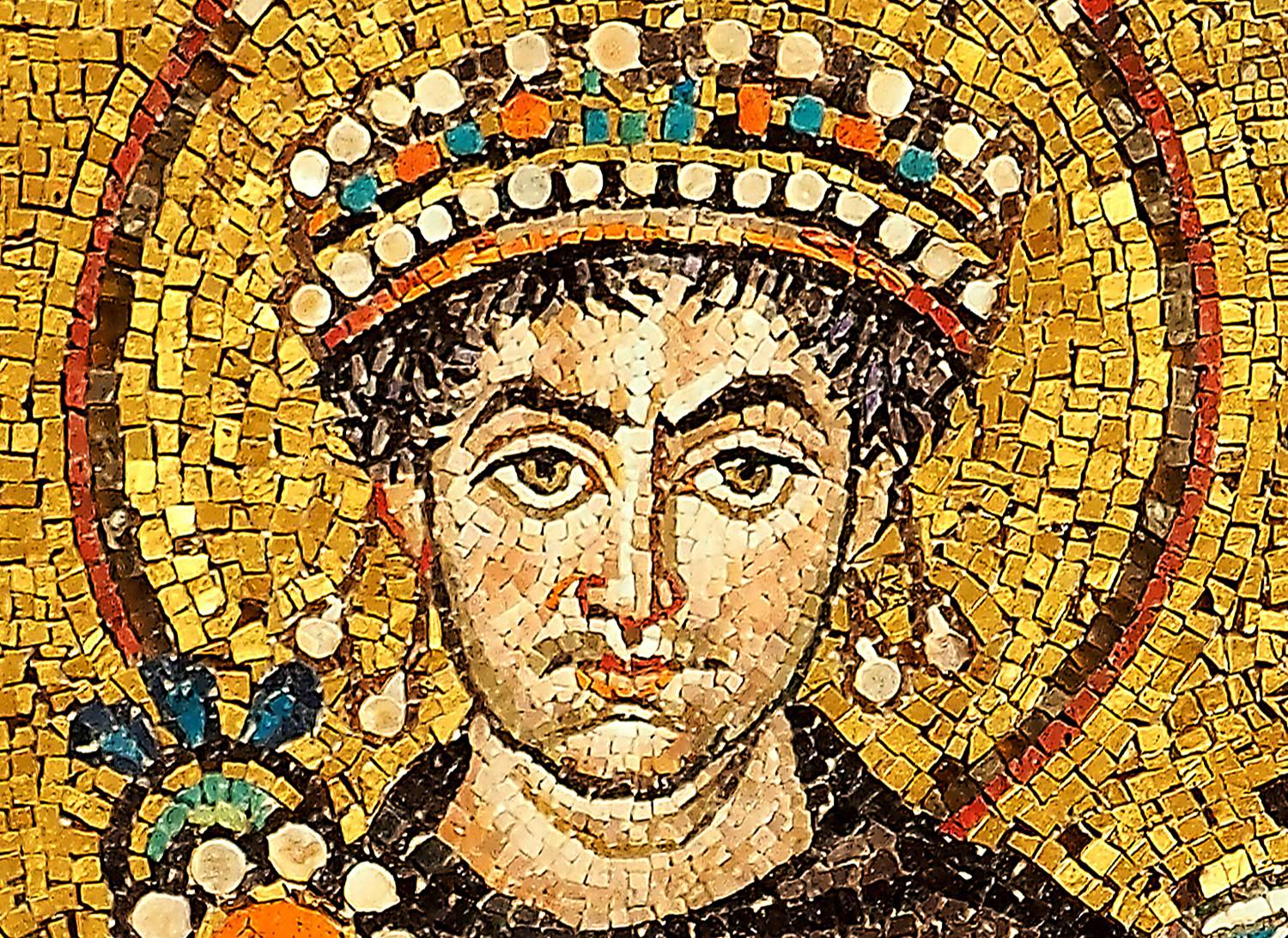

Eastern Overtime

It’s also notable that the Eastern Roman Empire had lots of problems, eventually falling to the Ottoman Empire in 1453. But the Byzantine Empire (as it was rebranded) lasted a whole lot longer than the Western Roman Empire, and dominated the region for centuries.

Petar Milošević, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Petar Milošević, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Guarding The Guards

Certainly, Rome was plagued by a lot of lousy emperors. Succession was complicated, with emperors usually dispatched by rivals. Making things worse, the Praetorian Guard, tasked with being the Emperor’s bodyguards, sometimes stepped outside their brief and deposed the existing one.

Jamie Heath, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Jamie Heath, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Cause For Alarm

“Surprise” was the watchword. After the notorious Emperor Nero’s demise in a revolt, Rome counted four emperors in the year 69 CE: Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and Vespasian. The first three met violent ends. Unusually for an emperor, Vespasian retired voluntarily, dying of natural causes.

Henryk Siemiradzki, Wikimedia Commons

Henryk Siemiradzki, Wikimedia Commons

A Chill Wind

It wasn’t just the political climate that was perilous. The Mediterranean region had been unusually warm from 200 BCE to 150 CE, then cooled off, and really cooled off after 450. Farming became a challenge and infantry harder to keep on as the weather turned miserable.

Diego Delso, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Diego Delso, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

High-Pressure System

Climate change may also have helped drive the Huns westward, producing a domino effect that pushed other groups to flee toward the Empire’s borders. And all that trade could bring new diseases, such as the Antonine Plague that may have felled a tenth of the Empire’s population.

Budget Stretching

At its peak, the Roman Empire stretched from the Atlantic to the Persian Gulf, an impressively big area with an impressively big budget. But big problems such as the Sassanid Empire in the east, internal conflicts at home, various plagues, and Germanic invasions drained coffers.

Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Wikimedia Commons

Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Wikimedia Commons

Long Red Tape

Increasing the bureaucracy helped ensure enough money to spend on defense, but centralized planning and higher taxes made it harder for Roman merchants to thrive. And in a big empire, the Emperor could be out of touch, with intermediaries paying for influence in distant realms.

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Artist, Wikimedia Commons

Not So Proud

Many elite families paid little tax, increasing the gap between rich and poor, fueling resentment. As civic pride went down, so likely did recruitment among Roman citizens. To fill the gaps, leaders turned to “barbarian” recruits who might feel little allegiance to the Empire.

Diego Delso, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Diego Delso, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Down The Drain

And despite its technological achievements, the Roman Empire suffered from pretty basic problems. Impressive aqueducts couldn’t guarantee cleanliness, especially if sewage ran down open drains. And all the fountains in Rome likely boosted the rate of water-borne malaria.

Benh LIEU SONG, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikipedia

Benh LIEU SONG, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikipedia

A Powerful Force

Getting back to historian Edward Gibbon, his theories have been influential, but also controversial. He saw the rising power of Christianity as a force that weakened Roman institutions and traditions. As an 18th-century English intellectual, Gibbon was hostile to Catholicism and the influence of priests.

A Complex Argument

But a strong argument can be made that pagan institutions, not Christianity, had weakened the Roman budget. Pagan temples and complexes drained government funds, with religious personnel maybe reaching half the size of the army, hence reducing the pool of recruits.

Lin Gaozhi, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Lin Gaozhi, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Hard To Judge

And defense issues had little to do with Christianity. Favoritism and corruption may have gone up in the fourth century, yet the Empire still seemed able to mount defenses. However, starting to billet recruits or to pay them with land may have reduced discipline and readiness.

Sailko, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Sailko, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Taking Its Toll

A century later, the ineptitude of most emperors combined with corruption among defense leaders was likely taking a toll. Aristocrats in the Senate had little interest in paying for fighters, and town councils despaired when local strongmen took power and property.

Cesare Maccari, Wikimedia Commons

Cesare Maccari, Wikimedia Commons

Morality Tale

Some still implausibly try to tie Rome’s decline with a moral decline due to Christianity, which was pretty prudish and restrained compared to the amorous indulgences of earlier emperors such as Caligula or Nero. They argue that this restrained lifestyle led to less investment in the Empire. However, the number of wealthy Christians was nothing compared to the number of corrupt Imperial bureaucrats.

José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Decline And Fall Of Population

While some theories are still criticized, a steep drop in population seems real. The city of Rome may have housed a million people in its classical heyday before dropping to just 6,000 in the sixth century. It’s hard to know if fertility was pushed down by a richer lifestyle, plagues, skirmishes, or lead poisoning.

Phillip Capper, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Phillip Capper, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Early Depression

Also, as the Empire’s expansion slowed, then reversed, a cheap supply of captives for the slave market greatly declined, with farming and manufacturing seriously affected. The economy may have slid into a depression two centuries before any “official” timeline of the Empire’s fall.

Jebulon, CC0, Wikimedia Commons

Jebulon, CC0, Wikimedia Commons

A Matter Of Geography

Further complicating the issue is that the Eastern Roman Empire shared many of the challenges that Rome faced in the West. What does look different is that Constantinople’s territories had a more protected geography, maybe encouraging the Huns and others to look elsewhere.

Jebulon, CC0, Wikimedia Commons

Jebulon, CC0, Wikimedia Commons

The Lessons Of Time

We may never really know why the Roman Empire collapsed. It seems to have been a slow process punctuated by occasional surprises. We all like a good story, but maybe Rome’s is a tale of how history isn’t always obvious—and that some lessons are learned too late.

You May Also Like:

The Brutal Realities Of Ancient Rome

The Tribe Rome Couldn’t Conquer

FeaturedPics, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

FeaturedPics, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19