Society Before Agriculture Began

An unassuming prehistoric site is forcing scholars to rethink civilization itself, showing how cooperation and engineering flourished among hunter-gatherers who organized landscapes, labor, and meaning thousands of years earlier than expected by global consensus.

Fatma Sahin, CC0, Wikimedia Commons, Modified

Fatma Sahin, CC0, Wikimedia Commons, Modified

Discovery In The Limestone Hills

Archaeologist Dr. Fatma Sahin and her team discovered Cakmaktepe in 2021 using satellite imagery analysis in southeastern Turkey's Sanliurfa province. Surface surveys revealed flint tools and circular structures carved into limestone bedrock.

Fatma Sahin, Wikimedia Commons

Fatma Sahin, Wikimedia Commons

Japanese And International Teams

Excavations involve collaboration between Cukurova University, Sanliurfa Archaeological Museum, and Japan's University of Tsukuba. The international effort brings diverse expertise to unraveling this complex site. Turkey's Ministry of Culture coordinates the broader Tas Tepeler Project.

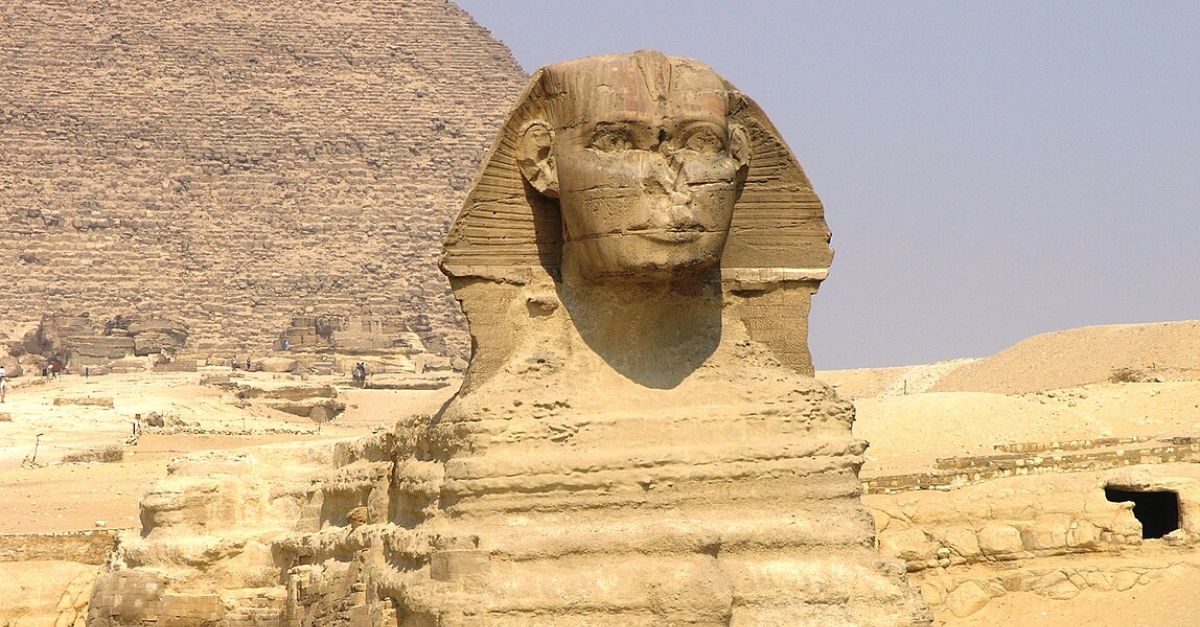

Damien Halleux Radermecker, Wikimedia Commons

Damien Halleux Radermecker, Wikimedia Commons

Part Of The Tas Tepeler Complex

Cakmaktepe belongs to Tas Tepeler, meaning Stone Hills—a 124‑mile region containing 12 major Neolithic sites. These include Gobekli Tepe, Karahan Tepe, and Sayburc, all dating to 12,000–9,000 years ago. Together, they represent the world's earliest evidence of organized settlement.

Eylem Özdoğan, B. Köşker, K. Akdemir, Wikimedia Commons

Eylem Özdoğan, B. Köşker, K. Akdemir, Wikimedia Commons

Dating To 10,000 BCE

El-Khiam points and flint chipped stone tools date Cakmaktepe to 10,000–9,500 BCE during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A period. Carbon-14 dating hasn't been completed, but artifact evidence points to extreme antiquity.

Older Than Gobekli Tepe

Gobekli Tepe shocked the world when it was discovered in 1994, dating to 9,500 BCE. Cakmaktepe pushes this timeline back further, which shows that monumental construction began even earlier. The site represents a more primitive architectural stage.

Location Near Sanliurfa

The settlement sits 12 miles southwest of Sanliurfa city on the Fatik Mountains' limestone plateau at an elevation of 2,198 feet. The area offered limestone for building, wild grains for gathering, and game for hunting. Geography made this location ideal for early experimentation with permanent living.

Hunter-Gatherers Who Didn't Farm

No domesticated plants or animals existed at Cakmaktepe—people hunted gazelles and gathered wild barley and wheat. Stone carvings depict antelope hunts, proving organized group hunting. These communities built permanent structures before agriculture even began, which challenges everything historians thought about civilization's origins.

Circular Structures Carved From Bedrock

Buildings at Cakmaktepe were created by hacking directly into limestone bedrock, and they formed circular floors 10–16 feet in diameter. Some areas show early terrazzo flooring attempts using gravel where bedrock sloped. This wasn't a random shelter; it was engineered architecture requiring planning and skill.

The 52-Foot Communal Building

Excavators uncovered a fully intact circular public building 52 feet in diameter, carved into bedrock. Post holes suggest roof supports, while a bench ran along the wall. A peculiar 5‑foot square structure with one open side sits in the southern section, purpose unknown.

Fatma Şahin, Wikimedia Commons

Fatma Şahin, Wikimedia Commons

Intentional Burial Of Structures

Similar to Gobekli Tepe, which was also deliberately backfilled, Cakmaktepe's buildings were dismantled and buried with care. Stones from pillars and walls were carefully placed aside, and then the entire structure was filled with soil. This ritual closure suggests profound cultural significance beyond simple abandonment.

German Archaeological Institute, photo E. Kücük., Wikimedia Commons

German Archaeological Institute, photo E. Kücük., Wikimedia Commons

Cone-Shaped Mortars In Floors

Carved directly into bedrock floors are conical holes of various sizes and depths. Similar to Natufian settlements in the Levant, these functioned as mortars for grinding wild grains and processing food. They represent the transition toward organized food preparation before farming existed.

Evidence Of Dense Population

The prevalence of pit-based shelters suggests both concentrated population and favorable environmental conditions. Structures cluster tightly across the 492‑foot diameter settlement, with additional buildings scattered beyond the core. This density indicates sustained habitation, not temporary camps.

Millstones And Grinding Tools

Stone millstones found throughout the site reveal systematic processing of gathered wild plants. These weren't crude rocks. They were shaped tools designed for specific tasks. Organized food preparation supported larger groups than individual families could manage alone.

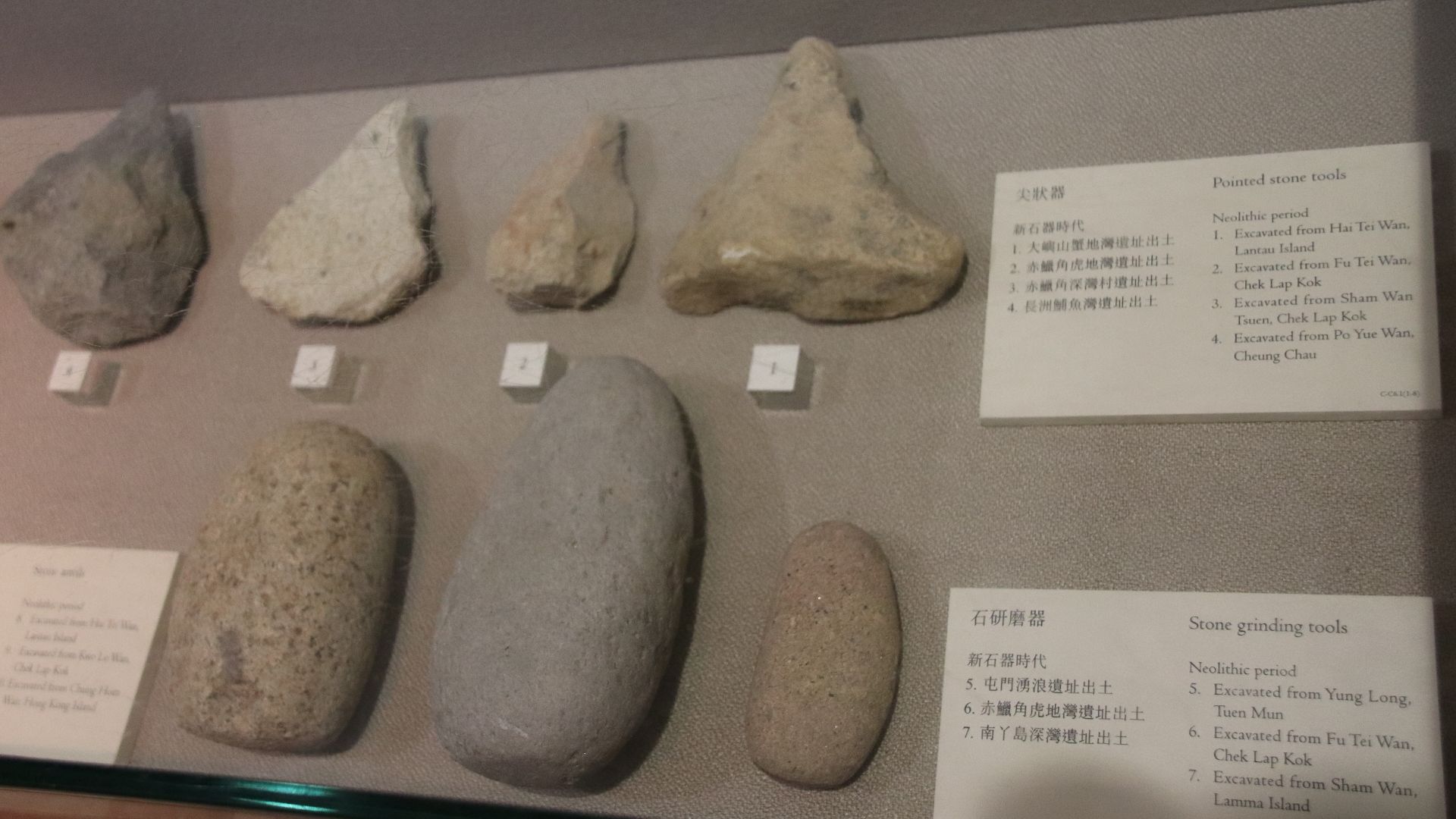

Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, Wikimedia Commons

Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, Wikimedia Commons

No Individual Houses Yet Found

While clear individual family dwellings remain limited, pit-based shelters indicate some residential use alongside communal structures. The site contains communal structures and food processing areas but lacks obvious private residences. People may have gathered here seasonally for rituals while living elsewhere.

Burnt Animal Skull Rituals

Building 15, excavated in 2024, contained carefully placed burnt animal skulls at wall bases. Wild cattle, sheep, horses, and gazelle skulls were burned elsewhere and then carried inside. Researchers believe these functioned as ceremonial masks in rituals, revealing complex spiritual practices.

Desert Kites For Mass Hunting

Surveys around Cakmaktepe revealed numerous desert kites—long stone walls funneling animals into traps. These massive structures required coordinated group effort and strategic planning. Collective hunting enabled meat storage and supported sedentary living before domestication began.

Fatma Şahin, Wikimedia Commons

Fatma Şahin, Wikimedia Commons

Two Construction Phases Identified

Building 20 shows two distinct phases. It was first carved directly into bedrock, and later renovated by adding interior walls to narrow the space. This architectural evolution proves sustained occupation over extended periods. The site wasn't built and abandoned, but actively modified across generations.

Frantisek Trampota, Wikimedia Commons

Frantisek Trampota, Wikimedia Commons

Comparison With Neighboring Sites

Cakmaktepe lies 1.2–1.9 miles from other Pre-Pottery Neolithic settlements like Sayburc, Yogunburc, and Ayanlar. This tight cluster suggests interconnected communities sharing resources and ideas. The region functioned as a network of early settlements experimenting with permanent living.

Frantisek Trampota, Wikimedia Commons

Frantisek Trampota, Wikimedia Commons

Why No T-Shaped Pillars

Unlike Gobekli Tepe's iconic T-shaped pillars representing humans or gods, Cakmaktepe lacks these monumental stones. The site predates this architectural tradition, showing what came before the pillar culture emerged. It's a missing link revealing how these symbolic forms evolved.

What They Ate And Drank

Wild lentils, wheat, barley, and chickpeas grew naturally in the surrounding steppe. Moreover, gazelles, wild cattle, and sheep provided meat from organized hunts. No pottery exists, so liquids were stored in stone vessels. Life revolved around gathering and hunting—agriculture was still centuries away.

Link To The Later Agricultural Revolution

Cakmaktepe's food processing tools and sedentary lifestyle laid the groundwork for farming's eventual emergence. Learning to store food and coordinate labor created conditions where agriculture could develop. Civilization didn't begin with farming; farming became possible because settlements like this existed first.

Superior Skills At Settlement's Start

The precision of carved bedrock structures, organized layouts, and communal buildings reveals unexpected sophistication. These weren't primitive people stumbling toward civilization. They possessed advanced knowledge and planning abilities. Their skills challenge assumptions about human capabilities 12,000 years ago.

Spica-Vega Photo Arts (Banu Nazikcan), Wikimedia Commons

Spica-Vega Photo Arts (Banu Nazikcan), Wikimedia Commons

Only 10% Of Site Excavated

Ground-penetrating radar and surveys reveal vast unexplored areas beneath the surface. Most structures remain buried, protecting secrets about how these communities lived. Excavation will continue for decades, gradually exposing more of humanity's earliest organized settlement.

Preservation In A Dry Climate

Turkey's arid southeastern climate protected organic materials and architectural details for 12,000 years. Moisture would have destroyed much of this evidence elsewhere. Geography and climate conspired to preserve this irreplaceable window into humanity's transition toward civilization.