A Prehistoric Trade Network Hidden In Plain Sight

For years, archaeologists working in Alberta noticed something strange. Among stone tools made from local rock, they kept finding obsidian. This was surprising. Alberta has no volcanoes. Obsidian only forms near volcanic activity. Somehow, this volcanic glass had traveled a very long way to get there. That mystery sparked a closer look. What researchers uncovered was not a handful of odd finds, but proof of a vast trade network. Long before modern roads or borders, Indigenous communities were moving materials across enormous distances. Obsidian was one of them.

What Makes Obsidian So Special?

Obsidian is volcanic glass. When lava cools quickly, it forms a hard, shiny stone that breaks into extremely sharp edges. For ancient people, this made obsidian perfect for tools. It could be shaped into knives, scrapers, and arrow points that were sharper than most other stone tools. But obsidian was valuable for another reason. Each volcanic source produces obsidian with a unique chemical makeup. That means archaeologists can tell where it came from. In a way, obsidian remembers its birthplace.

TheUltimateGrass, Wikimedia Commons

TheUltimateGrass, Wikimedia Commons

Finding Obsidian Where It Shouldn’t Be

Alberta is far from any volcanic region. There is no local source of obsidian. So every piece found there had to be carried in by people. At first, researchers thought these might be rare items brought back by travelers. But the number of finds told a different story. Obsidian kept appearing at sites across the province. Campsites. Hunting areas. Tool-making locations. This was not an accident. It was a pattern.

The Alberta Obsidian Project Begins

To understand that pattern, researchers launched the Alberta Obsidian Project. Their goal was simple: find out where the obsidian came from. They gathered artifacts from museums and archaeological collections. They also studied newly excavated material. In total, they examined obsidian from 96 sites spread across Alberta. The pieces dated back as far as 13,000 years ago. That long timeline suggested something important. These connections lasted for thousands of years.

How Scientists Tracked the Stone

The key tool was X-ray fluorescence, often called XRF. This method lets scientists measure the chemical elements in stone without damaging it. Because each volcanic source has its own chemical “fingerprint,” the results can be matched to known obsidian locations. With this technique, archaeologists could finally follow obsidian’s long journey.

Dwayne Reilander, Wikimedia Commons

Dwayne Reilander, Wikimedia Commons

Four Distant Sources Come Into Focus

The analysis revealed four main sources of obsidian. Some came from Bear Gulch in Idaho. Others came from Obsidian Cliff in Wyoming. Two more sources were found in British Columbia, including the Mount Edziza volcanic region. All of these places are far from Alberta. None are easy journeys on foot. Yet obsidian from all of them made its way north and east, across mountains, rivers, and plains.

A Journey Of Up To 750 Miles

Some obsidian pieces traveled nearly 750 miles. That distance is hard to imagine in a prehistoric world. These were not quick trips. They likely happened in stages. One group traded obsidian to another. That group passed it on again. Over time, the stone moved across the continent. Each exchange added another step to its story.

Trade Was About People, Not Just Objects

This was not simple bartering. Trade helped build relationships. It connected families and groups. It reinforced alliances and shared traditions. Obsidian was part of that social system. When people exchanged stone, they also exchanged knowledge, stories, and trust. The trade network was as much social as it was economic.

Ivan Petrovich Vtorov, Wikimedia Commons

Ivan Petrovich Vtorov, Wikimedia Commons

Bison Hunts As Meeting Places

Many obsidian artifacts were found near bison jump sites. These were places where large groups gathered to hunt. Bison hunts required cooperation and planning. They brought many communities together at once. These gatherings were perfect moments for trade. People could share tools, materials, and news. Obsidian likely changed hands during these events, moving farther with each meeting.

Rivers Helped Shape The Network

In northern Alberta, obsidian seems to follow river routes. Rivers made travel easier. They offered food, water, and clear paths through the land. By following rivers, people could move safely and efficiently. Over generations, these waterways became reliable trade routes that connected distant regions.

Ron Cogswell from Arlington, Virginia, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Ron Cogswell from Arlington, Virginia, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Every Artifact Tells A Human Story

Each obsidian tool was once held by a person. Someone shaped it. Someone used it. Someone carried it to a new place. These objects passed through many lives before ending up in the ground. When archaeologists find obsidian, they are not just finding stone. They are finding traces of relationships.

James St. John, Wikimedia Commons

James St. John, Wikimedia Commons

This Was Not Rare Or Accidental

The number of obsidian artifacts shows this was not a rare event. It happened again and again. The trade network did not collapse after a few generations. It endured. That kind of stability takes planning. It takes shared rules and expectations. It shows that these communities were organized and connected.

James St. John, Wikimedia Commons

James St. John, Wikimedia Commons

Long Before European Contact

All of this happened long before Europeans arrived in North America. These trade systems developed independently. They were adapted to local landscapes and seasonal movements. The idea that prehistoric communities were isolated no longer holds up. The evidence tells a different story.

Edward S. Curtis, Wikimedia Commons

Edward S. Curtis, Wikimedia Commons

How Many People Took Part?

Over thousands of years, countless people were involved. Some traveled long distances. Others stayed close to home but still played a role by passing goods along. Even those who never left their region were part of a much larger network. Their lives were connected to distant places they might never see.

Walter Cross, Wikimedia Commons

Walter Cross, Wikimedia Commons

Obsidian May Have Meant More Than Use

Obsidian was practical, but it may also have carried meaning. Owning stone from far away could show connections or status. It could represent friendships or shared ancestry. In this way, obsidian may have been a symbol as well as a tool.

Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, Wikimedia Commons

Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, Wikimedia Commons

A Pattern Seen Around The World

Archaeologists have seen similar obsidian trade networks in other parts of the world. In many ancient societies, obsidian traveled far from its source. The Alberta discoveries show that North America fits this global pattern. Long-distance trade is a deeply human behavior.

Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, Wikimedia Commons

Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, Wikimedia Commons

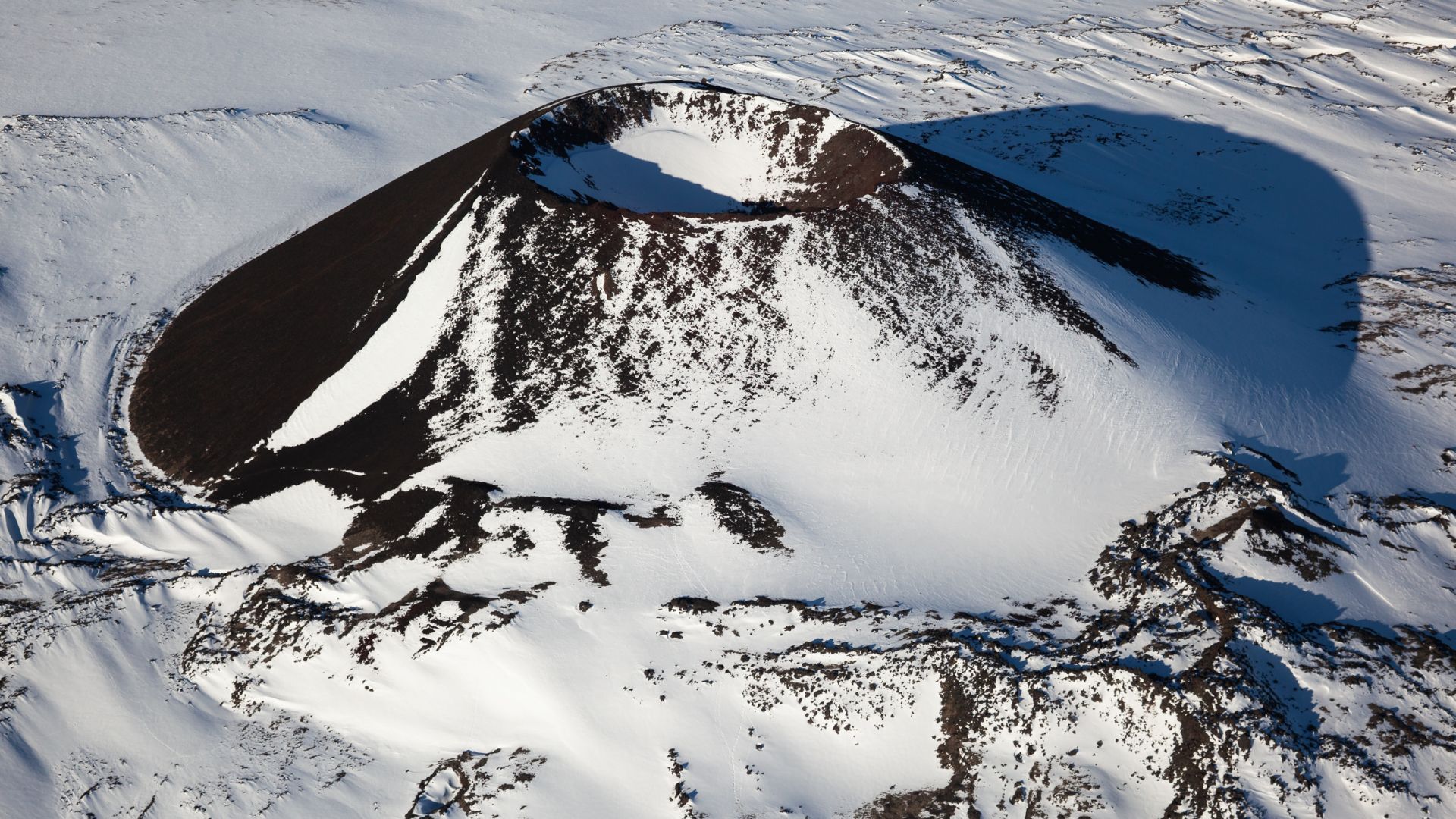

The Importance Of Mount Edziza

One source stands out: Mount Edziza in northern British Columbia. Obsidian from this area traveled great distances in many directions. Its presence in Alberta ties the province into a much larger web of movement that reached across western North America.

John Scurlock, Wikimedia Commons

John Scurlock, Wikimedia Commons

Why Bear Gulch Obsidian Stands Out

Bear Gulch obsidian appears often in Alberta sites. This suggests it was especially valued or especially well connected through trade. Its frequent appearance hints at long-standing relationships between communities far apart.

Eugene Zelenko, Wikimedia Commons

Eugene Zelenko, Wikimedia Commons

Indigenous Communities Shaped This World

These networks did not appear by chance. Indigenous peoples built them. They maintained them. They adapted them over time. This research highlights Indigenous knowledge, planning, and agency. It shows societies that were dynamic and forward-thinking.

Harris & Ewing, photographer, Wikimedia Commons

Harris & Ewing, photographer, Wikimedia Commons

New Technology Brings Old Stories To Light

Many of these artifacts were collected decades ago. Only now do archaeologists have the tools to unlock their full story. As technology improves, old collections continue to reveal new insights. The past still has much to say.

Library of Congress Life, Wikimedia Commons

Library of Congress Life, Wikimedia Commons

The Story Is Still Growing

Hundreds of obsidian sites are now known in Alberta. Many more may still be waiting to be discovered. Each new analysis adds detail to the picture. The map of ancient connections keeps expanding.

James St. John, Wikimedia Commons

James St. John, Wikimedia Commons

Rethinking Prehistoric Mobility

These findings challenge old ideas about how people lived in the past. Mobility was not limited. Communication was not rare. Prehistoric life was rich, connected, and full of movement.

BLM Oregon & Washington, Wikimedia Commons

BLM Oregon & Washington, Wikimedia Commons

What This Means Today

For Indigenous communities today, this research confirms deep histories of connection and exchange. It provides physical evidence of long-standing relationships with land and people. It also helps tell a more accurate story of the past.

Dwayne Reilander, Wikimedia Commons

Dwayne Reilander, Wikimedia Commons

Looking Ahead In Obsidian Research

Future studies may reveal even more detail. Researchers hope to understand how trade changed over time and how networks responded to climate and social shifts. Obsidian still has many stories left to tell.

Joshua Tree National Park, Wikimedia Commons

Joshua Tree National Park, Wikimedia Commons

A Network Beneath Our Feet

Beneath Alberta’s soil lies proof of an ancient web of movement and connection. Obsidian traveled far, but its journey was guided by human relationships. Those relationships shaped the land long before written history.

Yellowstone National Park, Wikimedia Commons

Yellowstone National Park, Wikimedia Commons

Stones That Still Speak

Obsidian may seem like just a sharp piece of stone. But it carries a powerful message. People have always reached beyond their horizons. Even thousands of years ago, human lives were linked across vast distances — one piece of volcanic glass at a time.

Yellowstone National Park, Wikimedia Commons

Yellowstone National Park, Wikimedia Commons

You May Also Like:

Sources: 1, 2, 3