Have You Ever Carved A Giraffe Into Rock? Not Like This You Haven't

High in the rugged sandstone plateau of southeastern Algeria, a vast open-air gallery has preserved thousands of images from a time when the Sahara was green. In Tassili n’Ajjer, researchers have documented over 15,000 prehistoric carvings and paintings—depictions of extinct megafauna, human life, and what may be ancient shamanic or ritual practices. Together, these images form one of the richest visual records of human adaptation, environment, and belief over more than 10,000 years. For archaeologists and history lovers alike, Tassili offers a window into a vanished world where art was a bridge between people, animals, and the forces of nature.

A Stone Archive On The Sahara’s Rim

High on a sandstone plateau in southeastern Algeria, researchers have documented more than 15,000 prehistoric images—both carvings and paintings—at Tassili n’Ajjer. These works chart climate changes, the shifting presence of wildlife, and the transformation of human societies over millennia, earning the site recognition as a UNESCO World Heritage treasure.

Where And What Is Tassili n’Ajjer?

The name “Tassili n’Ajjer” translates to “Plateau of the Ajjer (Kel Ajjer) people.” This landscape is a labyrinth of canyons, sandstone domes, and towering rock formations near the borders of Libya and Niger. It has long been a crossroads for Saharan cultures and offered an ideal natural canvas for rock art.

A Century Of Discovery

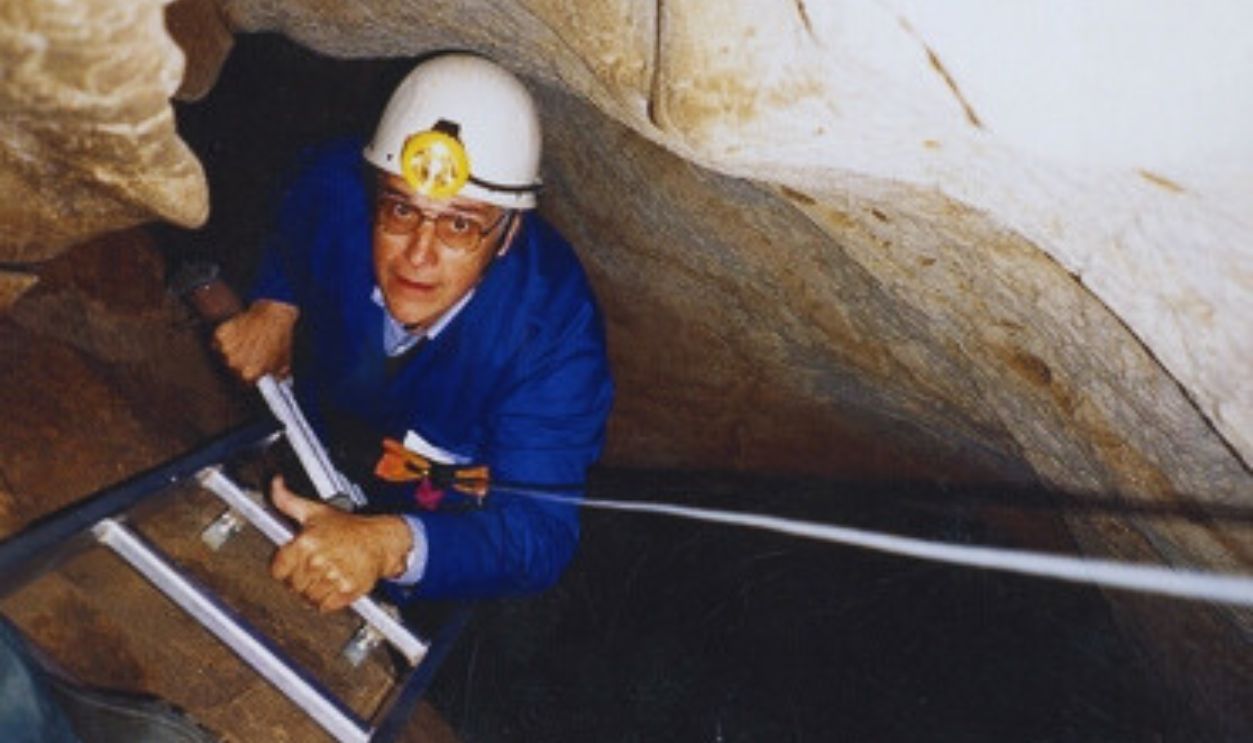

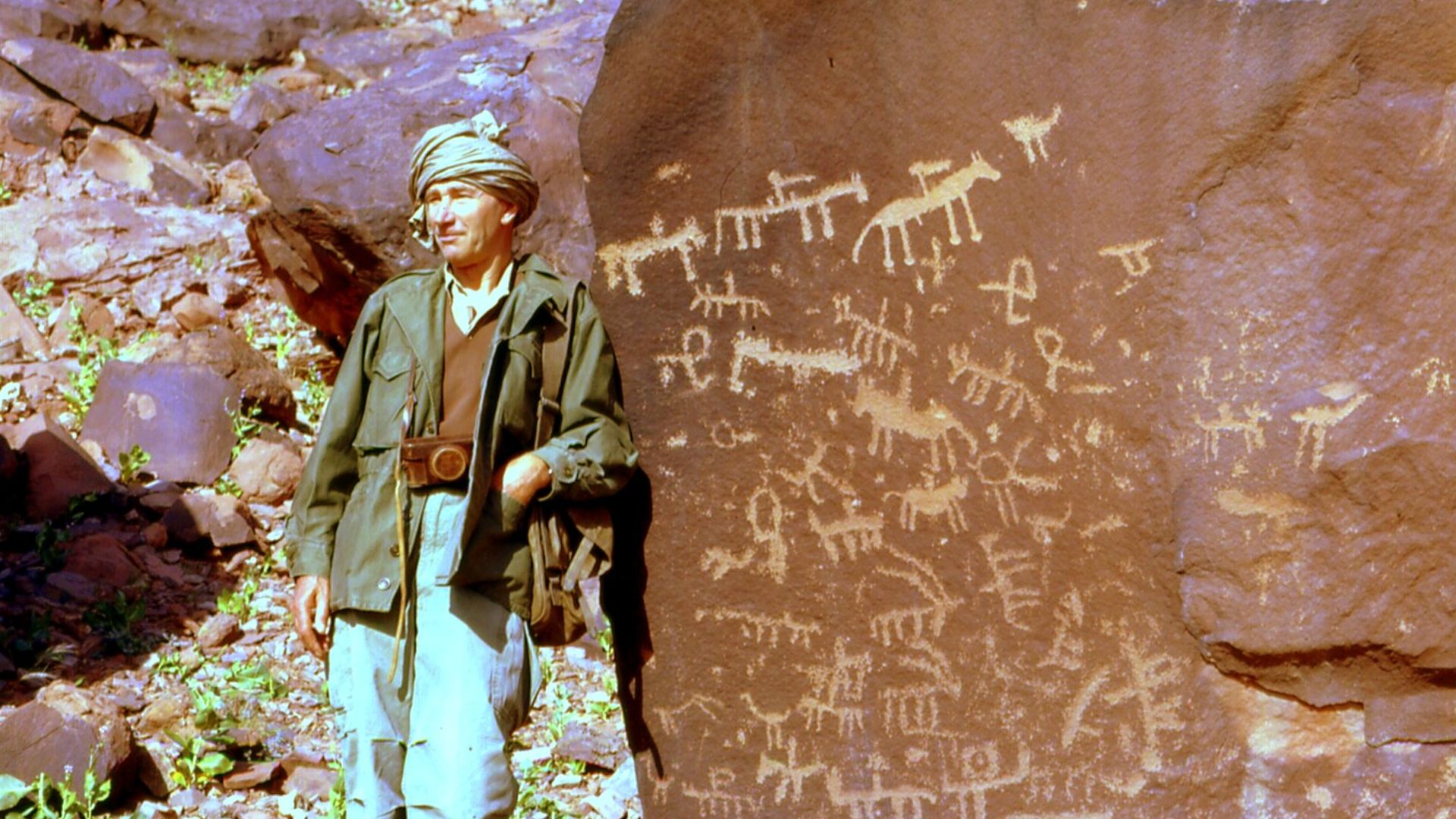

Although local Tuareg communities have known these shelters for generations, European awareness began to grow in the early 20th century, notably in the 1910s and 1930s, and again in the 1950s and 1960s when French explorer Henri Lhote publicized the site through high-profile expeditions and books. The history of its discovery is closely tied to debates over archaeological interpretation and methodology.

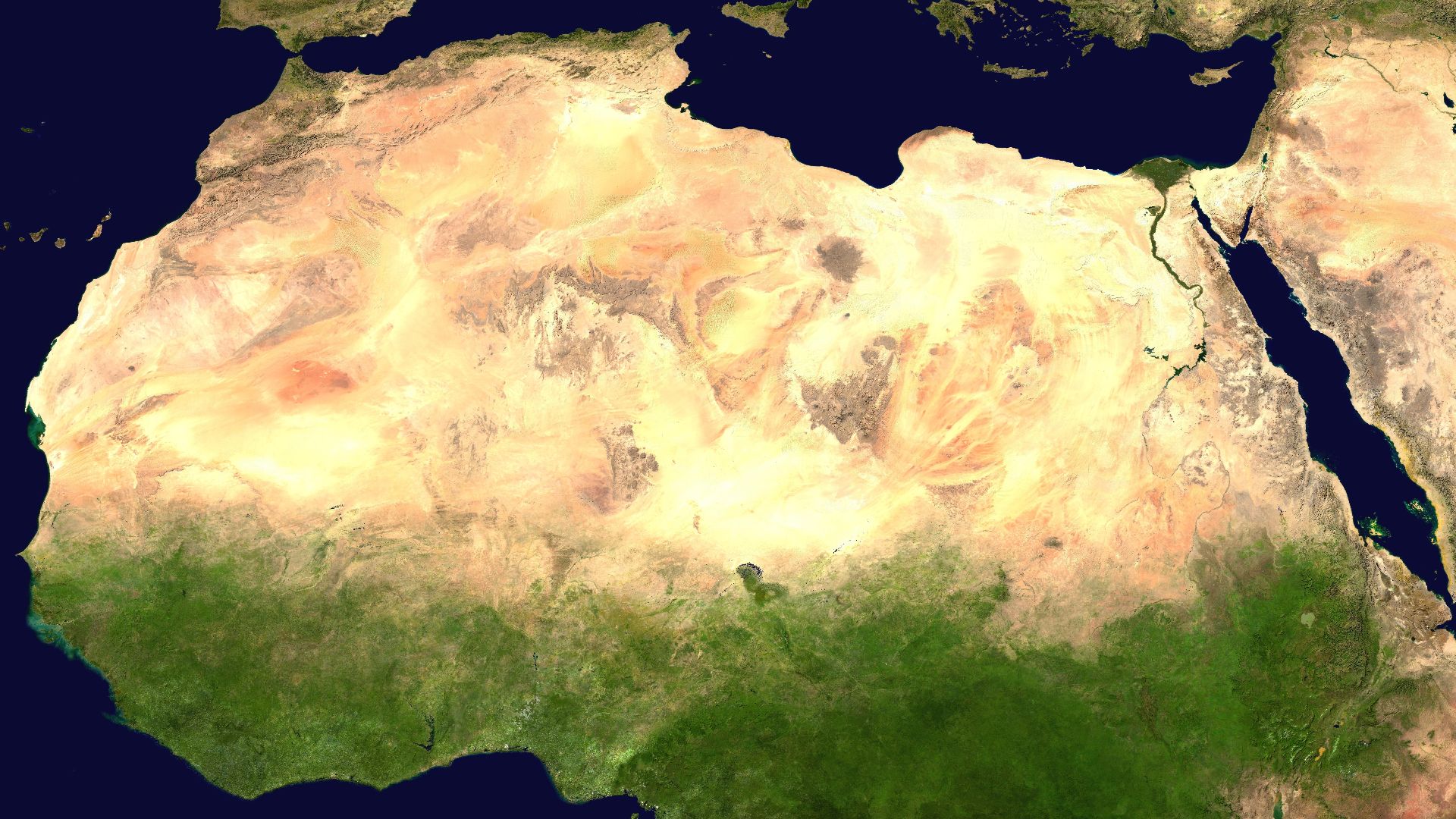

A Climate Time Machine

The images span the African Humid Period, a time when the Sahara was far greener and filled with lakes, rivers, and savannas, before gradually transforming into the desert of today. Scenes showing hippos, crocodiles, and cattle document this ecological shift in vivid detail.

How Old Is The Art?

Determining the age of the rock art is difficult because mineral pigments resist radiocarbon dating. Scholars instead rely on superimposition of images, stylistic analysis, and connections to excavated sites. A broadly accepted chronological sequence includes the Large Wild Fauna (Bubaline), Round Head, Pastoral (Cattle), Horse, and Camel periods.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Timeframe Overview

The Bubaline or Large Wild Fauna period likely dates from around 12,000 to 8,000 years ago, followed by the Round Head period from about 10,000 to 8,000 years ago. The Pastoral or Cattle period spans approximately 7,500 to 4,000 years ago, with the Horse period dating to 3,000 to 2,000 years ago, and the Camel period beginning around 2,000 years ago and continuing into recent history. While these ranges are widely used, they remain open to scholarly debate.

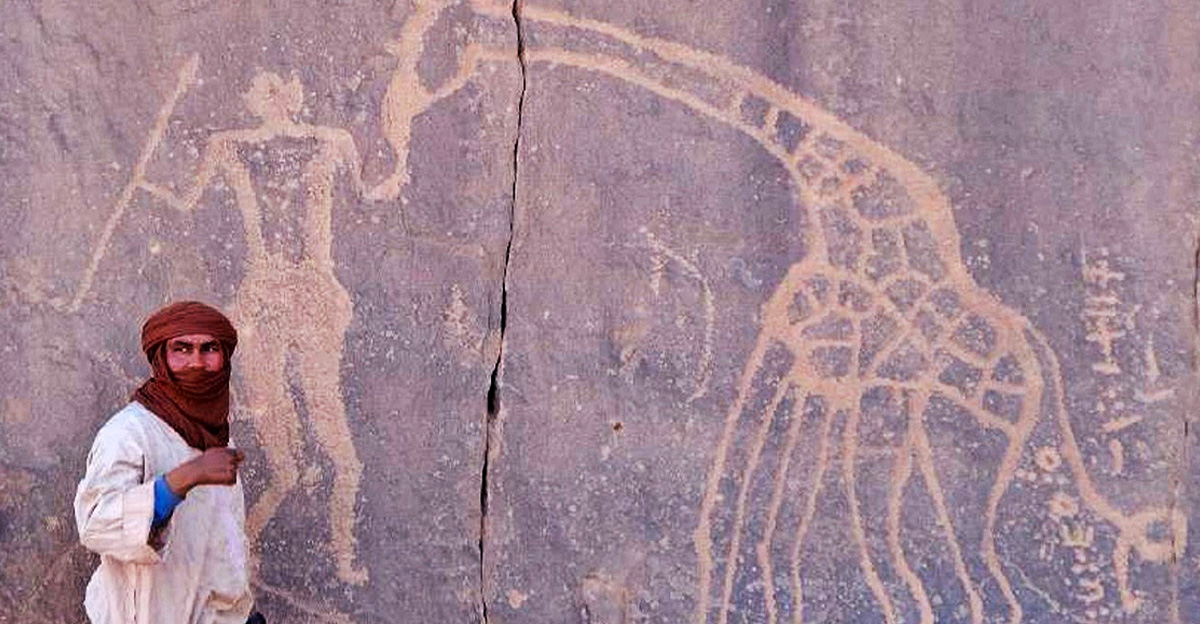

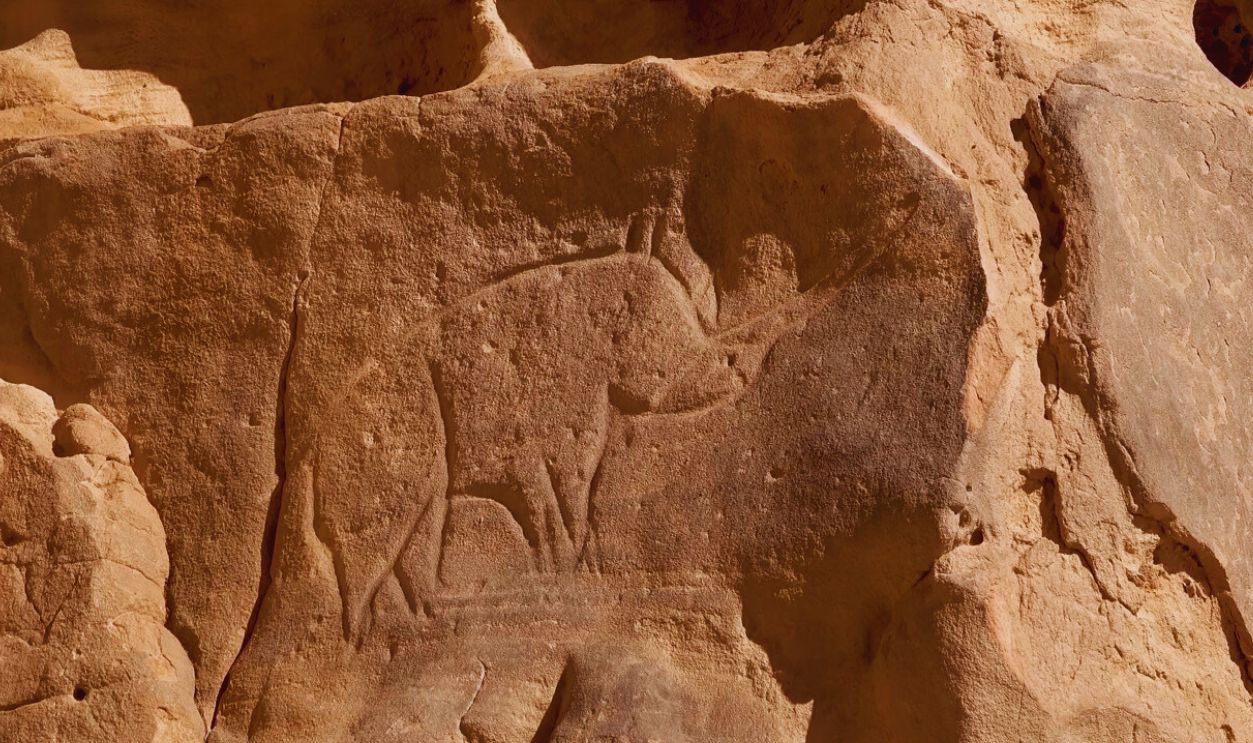

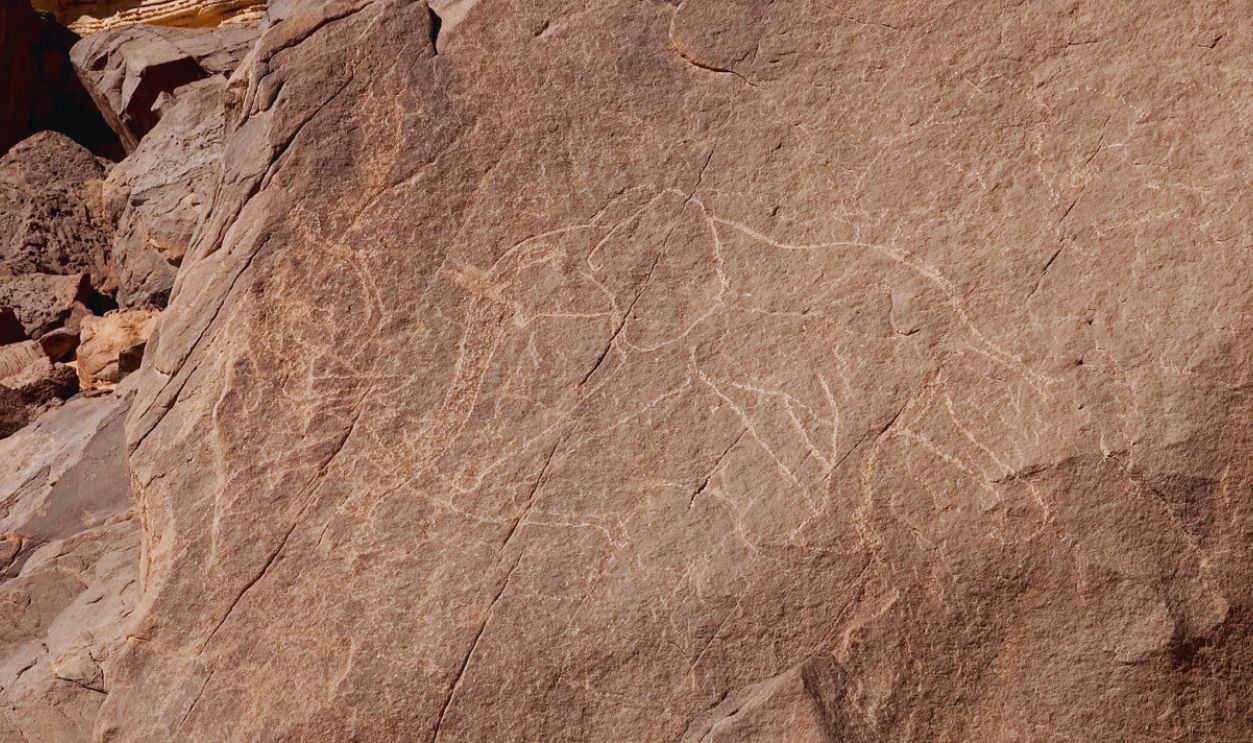

Carved Megafauna: The “Bubaline” Legacy

The earliest engravings often depict animals much larger than the human figures beside them. Elephants, rhinos, giraffes, and the now-extinct giant long-horned buffalo (Pelorovis/Syncerus antiquus) dominate these panels, with the buffalo’s vast, lyre-shaped horns serving as a defining motif.

Amazing SAHARA: Tassili n'Ajjer, Algeria [Amazing Places 4K], Amazing Places on Our Planet

Amazing SAHARA: Tassili n'Ajjer, Algeria [Amazing Places 4K], Amazing Places on Our Planet

Extinct Animals, Living Questions

These massive bovid depictions have sparked debate among scholars, with some arguing they truly represent Pelorovis/Syncerus antiquus, while others note details more reminiscent of Asian water buffalo. The discussion continues, as each engraving invites new interpretations.

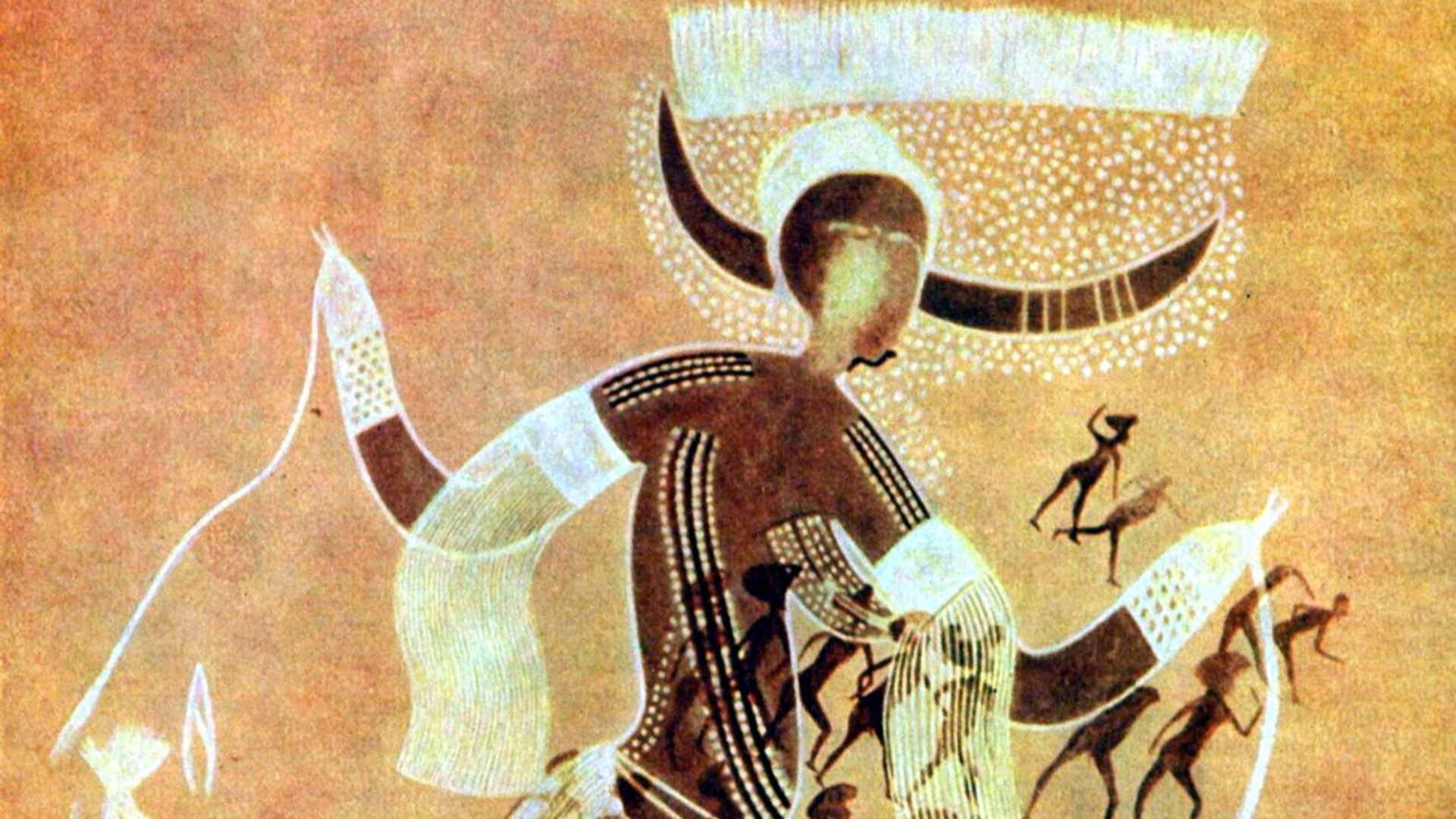

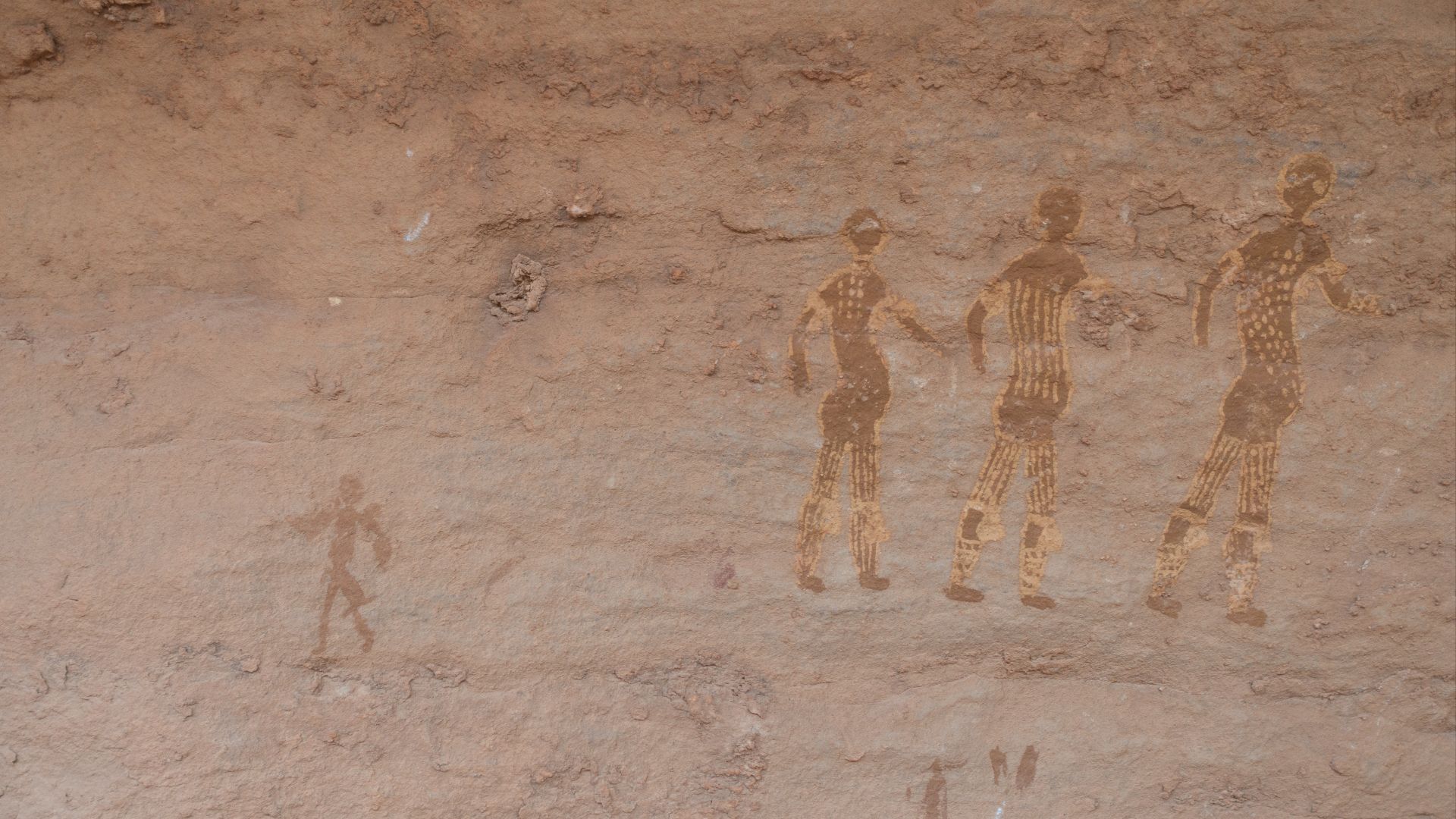

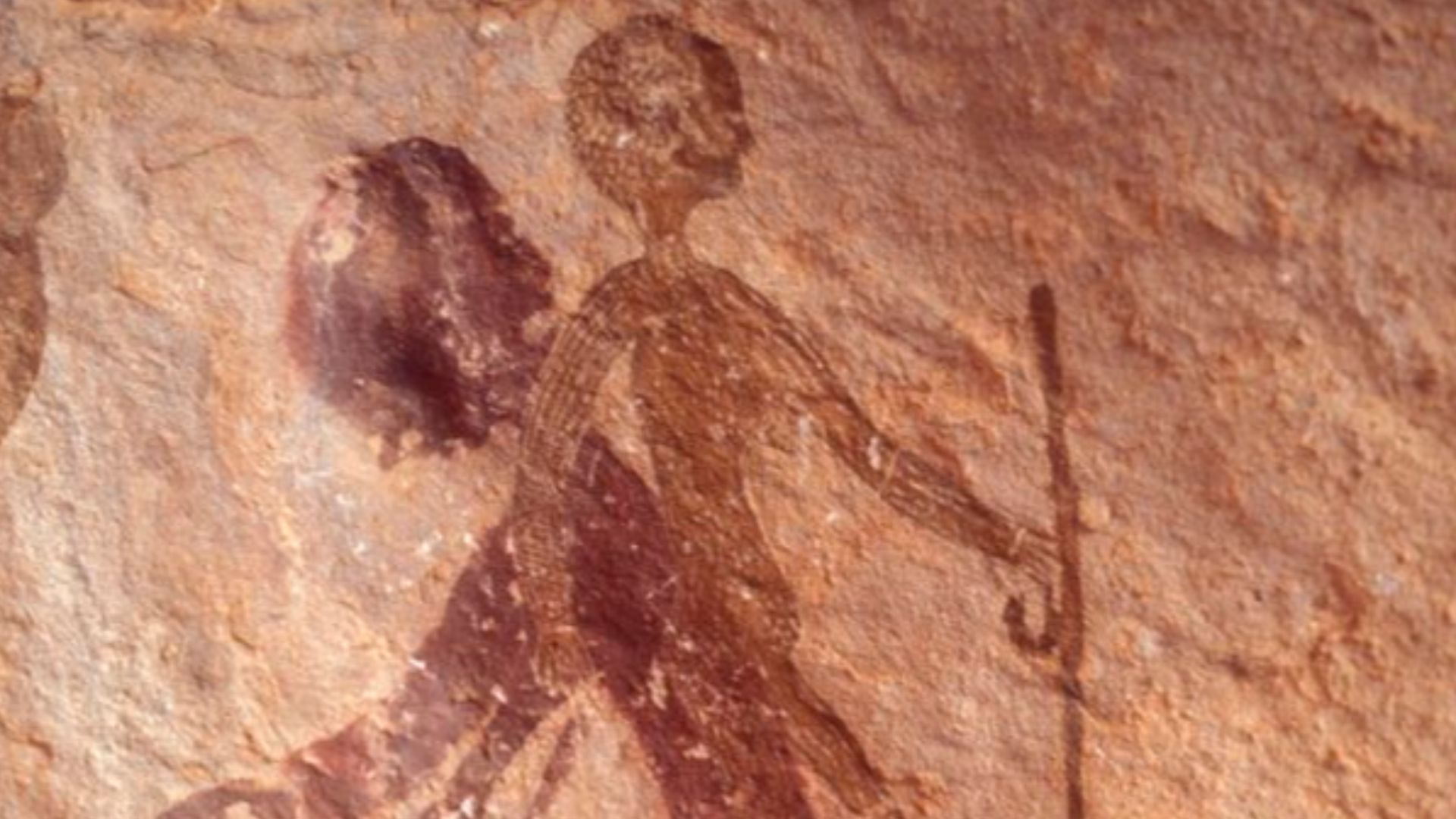

Enter The Round Heads

Later artistic phases shift the focus to human figures with featureless circular heads, elongated or amorphous bodies, and elaborate masks or headdresses. Many of these figures appear to float, dance, or process together, creating scenes that feel overtly ceremonial.

Afrikanischer Maler, Wikimedia Commons

Afrikanischer Maler, Wikimedia Commons

Rites On The Rock?

Because the Round Head paintings often emphasize masked performers, painted bodies, and altered postures, many researchers interpret them as depictions of rituals—perhaps trance dances or initiation ceremonies. The British Museum has noted that clusters of certain motifs may even identify sites used for ritual gatherings.

Alessandro Passaré, Wikimedia Commons

Alessandro Passaré, Wikimedia Commons

The “Great God Of Sefar” And Other Giants

At the sites of Sefar and Jabbaren, enormous human-like figures with outstretched arms dominate the panels, surrounded by smaller attendants. These striking compositions have become central to the debate over whether the art represents ritual or shamanic activity.

Ancient men, Wikimedia Commons

Ancient men, Wikimedia Commons

Shamanism: Powerful Model, Ongoing Debate

The anthropologist J.D. Lewis-Williams has famously suggested that rock art across the world can reflect trance states and shamanic practices. Yet critics caution against applying this interpretation too broadly. In Tassili’s case, it is fair to speak of possible rites, but unproven shamanism, given the lack of direct evidence.

Jean Clottes/Geoff Blundell, Wikimedia Commons

Jean Clottes/Geoff Blundell, Wikimedia Commons

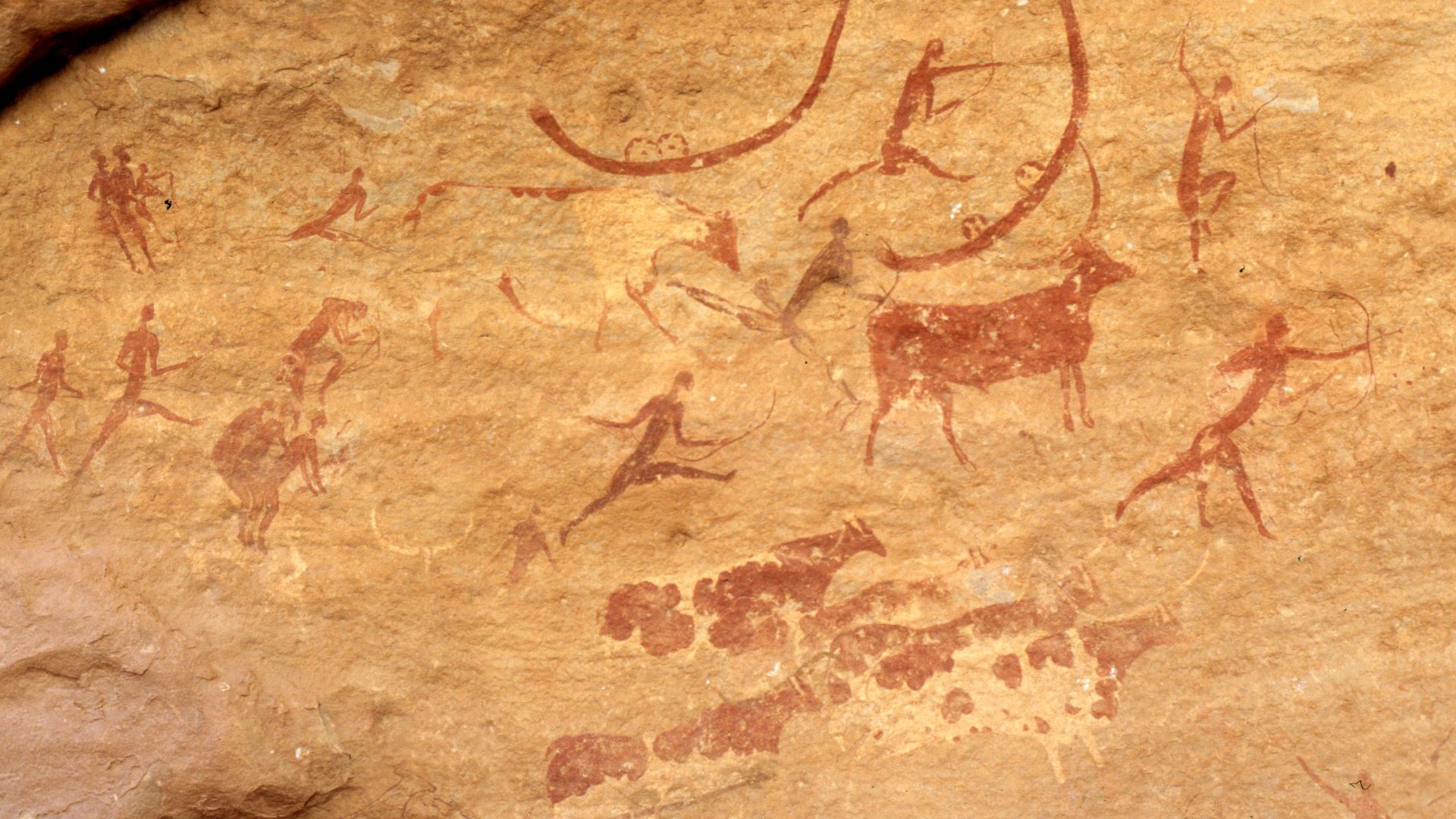

Pastoral Revolutions

By around 7,500 to 4,000 years ago, the art begins to feature herds of domesticated cattle, scenes of milking, and everyday village life, alongside images of wild fauna. These paintings and carvings offer a vivid portrayal of Neolithic herding communities thriving in a greener Sahara.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Horse Power And Spread Of Mobility

In later periods, depictions of horses and sometimes chariots emerge, symbolizing mobility, status, and control rather than literal races across the rocky terrain. As the climate dried further, horses gradually gave way to camels, which became central to survival and trade in the desert.

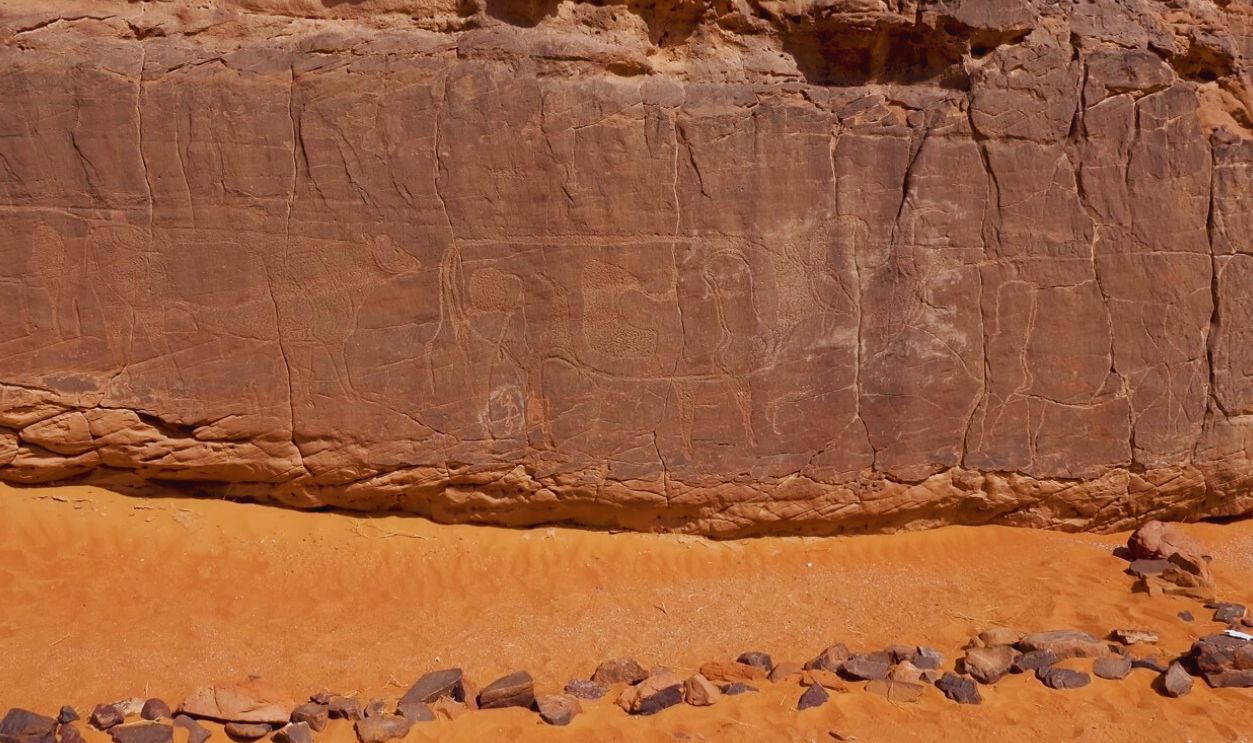

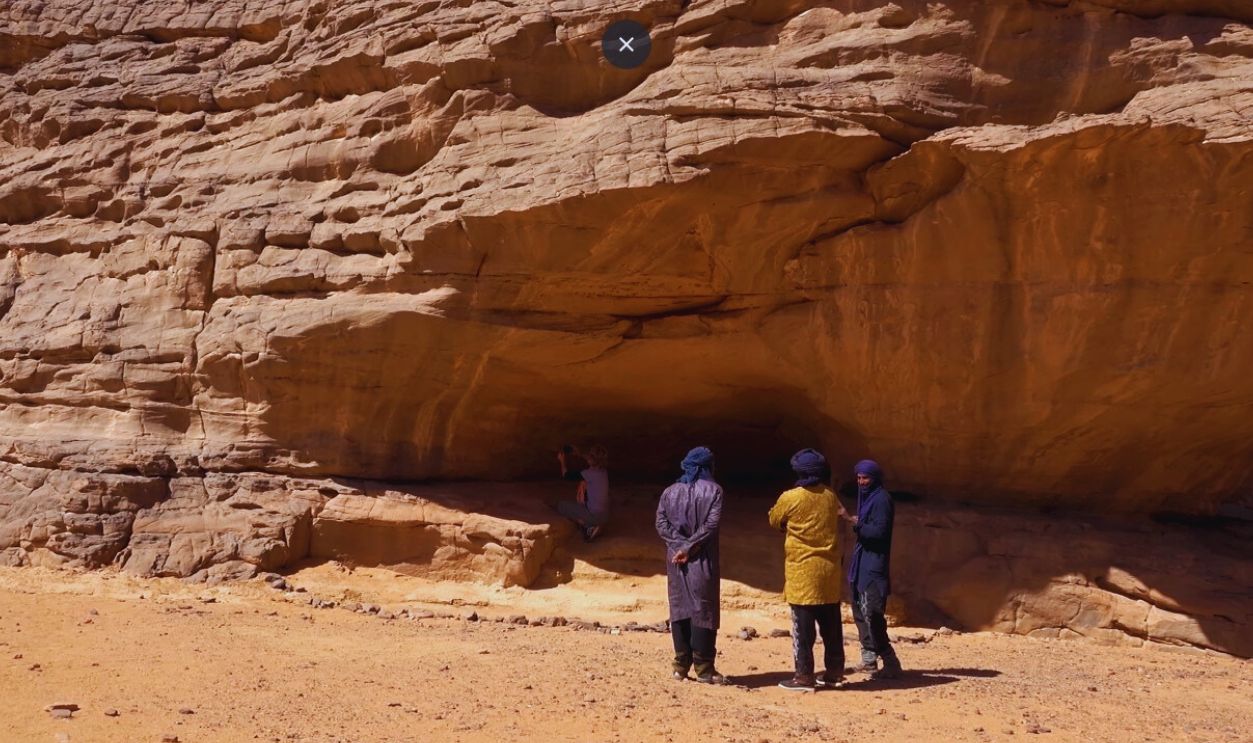

Why So Many Images Here?

The plateau’s soft sandstone provided an ideal surface for both pigment application and engraving, while the rock shelters shielded the art from weathering. In earlier times, the availability of water and the site’s location along seasonal routes made it a natural gathering place and artistic hub for thousands of years.

How Researchers Read The Walls

Scholars analyze the panels through tracing, digital imaging to clarify faint lines, mapping superimposed figures, and comparing stylistic details across sites. They also connect visual themes to archaeological finds or known climatic events, building a layered interpretation of the art’s history.

Patrick Gruban from Munich, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

Patrick Gruban from Munich, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

Everyday Life—And The Extraordinary

Within the same shelters, depictions of hunting parties, domestic scenes, herding, and communal dances are often found together. This combination suggests that the shelters functioned as memory spaces where identity, territory, and mythology could be visually recorded.

IssamBarhoumi, Wikimedia Commons

IssamBarhoumi, Wikimedia Commons

Materials And Techniques

Artists created pigments from ochre, kaolin, and other minerals, and used stone points and abrasive sand to carve engravings. Many works show fine contour lines, detailed infill, and even polychrome effects, revealing a high level of skill and consistent conventions passed down through generations.

Marco Almbauer, Wikimedia Commons

Marco Almbauer, Wikimedia Commons

Reading Climate In Animals

The presence of hippos and crocodiles in the art points to a landscape with permanent water sources, while giraffes and elephants indicate expansive savanna. Later depictions of camels align with the encroachment of desert dunes and the rise of trans-Saharan trade.

Amazing SAHARA: Tassili n'Ajjer, Algeria [Amazing Places 4K], Amazing Places on Our Planet

Amazing SAHARA: Tassili n'Ajjer, Algeria [Amazing Places 4K], Amazing Places on Our Planet

The Lhote Problem

Henri Lhote’s 1950s campaigns brought the site global fame but also drew criticism. Subsequent scholars have accused his team of over-painting, making errors in reproduction, and sensationalizing the finds, actions that may have damaged some panels and distorted interpretation.

gbaku, Wikimedia CommonsFrom “Martian Gods” To Measured Hypotheses

gbaku, Wikimedia CommonsFrom “Martian Gods” To Measured Hypotheses

Mid-20th-century media fascination with “astronauts” in the Sahara originated with Lhote’s fanciful nicknames for certain figures. Modern research identifies these as humans in elaborate ritual attire, illustrating how contemporary myths can attach themselves to ancient images.

Universal History Archive, Getty Images

Universal History Archive, Getty Images

What “Extinct Animals” Really Means Here

In this context, some animals such as Pelorovis/Syncerus antiquus are globally extinct, while others like giraffes and hippos still survive elsewhere but have vanished from the central Sahara. The combination of species reflects ecological changes across both time and geography.

Why The Number Matters

The figure of more than 15,000 images reflects decades of careful documentation across hundreds of shelters rather than mere estimation. This extraordinary density and the span of time represented make Tassili one of the most significant sites for tracing human adaptation through art.

Alessandro Passaré, Wikimedia Commons

Alessandro Passaré, Wikimedia Commons

Big Questions That Keep Scholars Busy

Researchers continue to ask whether Round Head masks are linked to specific clans or ceremonies, how the layering of images aligns with climate cycles, and whether new dating methods such as micro-erosion analysis or pigment chemistry could refine the chronology. These open questions help keep the site at the forefront of archaeological research.

Alessandro Passaré, Wikimedia Commons

Alessandro Passaré, Wikimedia Commons

Preservation Realities

The art faces threats from wind erosion, salt, vandalism, and unregulated copying. Organizations such as the Trust for African Rock Art, in partnership with Algerian authorities, are working to document and protect the 80,000-square-kilometer park that contains the images.

Visiting, With Care

Because the site is accessible only by long treks from the oasis town of Djanet, its remoteness has helped preserve it but has also made regular monitoring challenging. Responsible visitors are urged to follow local guides, avoid touching the panels, and leave no trace in these fragile environments.

Amazing SAHARA: Tassili n'Ajjer, Algeria [Amazing Places 4K], Amazing Places on Our Planet

Amazing SAHARA: Tassili n'Ajjer, Algeria [Amazing Places 4K], Amazing Places on Our Planet

What The Art Tells Us About People

From the earliest hunter-gatherers to later herders and traders, the artists of Tassili were adept at reading the land, managing resources, and embedding meaning in their imagery. Their art functioned as a kind of social technology, serving purposes of memory, instruction, and ceremonial expression.

Amazing SAHARA: Tassili n'Ajjer, Algeria [Amazing Places 4K], Amazing Places on Our Planet

Amazing SAHARA: Tassili n'Ajjer, Algeria [Amazing Places 4K], Amazing Places on Our Planet

What The Art Tells Us About The Sahara

The Sahara we see today is not a static desert but a landscape that has shifted dramatically over time. The rock art, alongside geological and environmental evidence, demonstrates that humans adapted in creative ways to a changing climate.

Alessandro Passaré, Wikimedia Commons

Alessandro Passaré, Wikimedia Commons

How Does This Change What We Know About The Sahara And It's Place In Human History?

The rock art of Tassili n’Ajjer is far more than a collection of ancient images—it is an evolving conversation between people and their environment, etched and painted over thousands of years. The buffalo and giraffes evoke vanished ecosystems, while the masked dancers suggest complex social and spiritual worlds. Together, they offer an irreplaceable record of resilience, creativity, and cultural continuity in one of the harshest environments on Earth. Protecting this archive ensures that future generations can stand in these sandstone shelters, gaze upon the same figures, and feel the enduring wonder of humanity’s deep past.

Camille Gillet, Wikimedia Commons

Camille Gillet, Wikimedia Commons

You May Also Like:

Ranking The Fastest Growing Cities In America

Places Around The World Where It's Illegal To Die

Photos Of The Mountain People Who Live At 15,000 Feet Year-Round