Desert Dominion

The Tuareg homeland covers a massive swath of the Sahara Desert. Traditionally nomadic pastoralists, they roamed an area stretching from the Libyan Fezzan in the northeast across southern Algeria and into Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso, reaching as far south as northern Nigeria. This vast territory made the Tuareg one of the most geographically widespread Berber ethnic groups, united by a common culture despite modern borders cutting across their domain—and facilitated their rise to become the lords of the Sahara.

Life On The Move

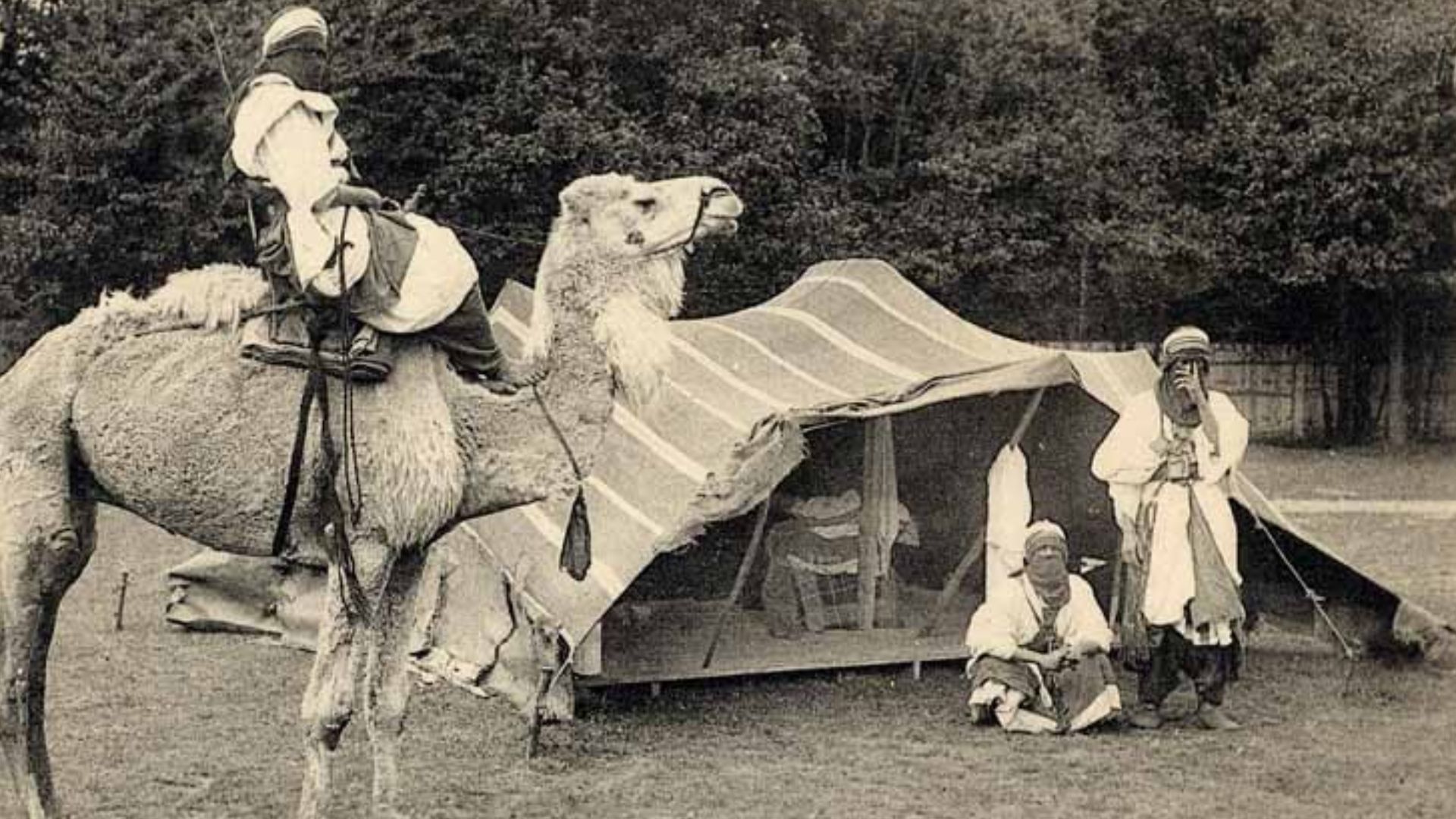

For centuries, the Tuareg lived as semi-nomadic herders and caravan traders, adapting to the harsh desert environment. Even today, many Tuareg either tend livestock in a nomadic lifestyle or have settled as farmers, while others continue as blacksmiths or caravan leaders across the Sahel. Their economy has traditionally revolved around pastoralism, breeding camels, goats, and cattle, supplemented by trade and some agriculture.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

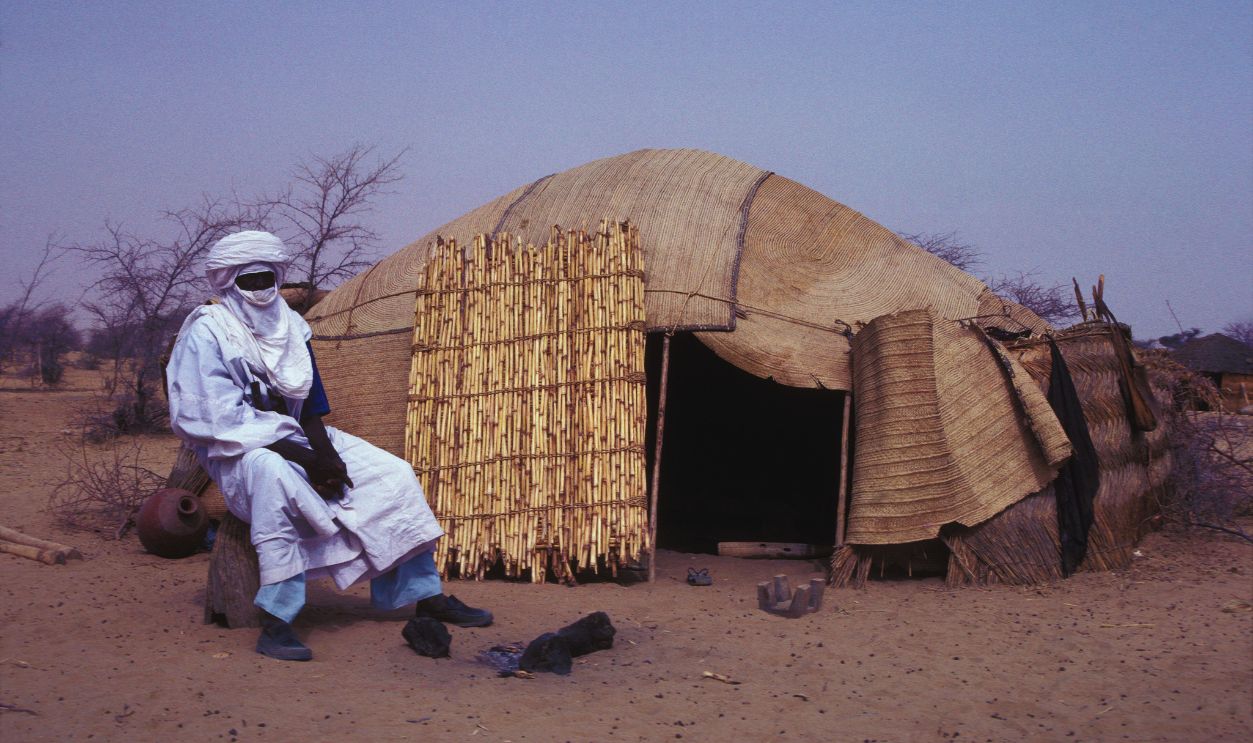

Caravans Of Salt

Since prehistoric times, Tuareg merchants have organized epic trans-Saharan caravans ferrying goods across the desert. They were famed for the salt caravans: the route from Agadez to the salt mines of Fachi and Bilma (in Niger) is called the Tarakaft or Taghlamt, while the trek from Timbuktu to Taoudenni (in Mali) is known as the Azalay. Tuareg caravans initially used oxen and horses, but later switched to camels, to haul heavy slabs of salt and other trade items across endless dunes. These camel caravans were the lifeline of Saharan commerce, linking West African communities with North Africa for generations.

Heribertus2, Wikimedia Commons

Heribertus2, Wikimedia Commons

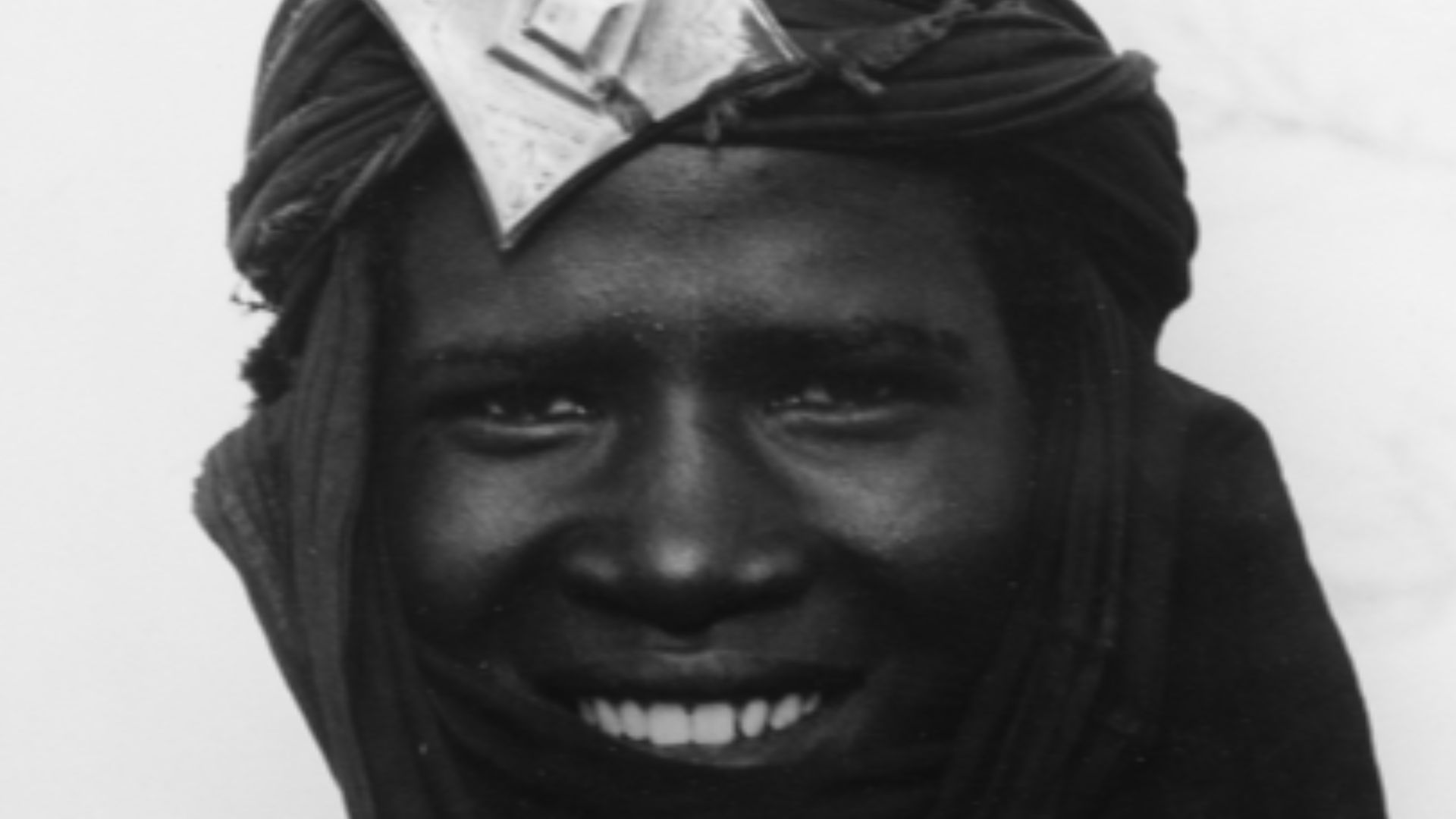

The “Blue People”

Europeans gave the nickname “Blue People” to the Tuareg for a colorful reason. Tuareg men traditionally wear deep indigo-dyed robes and veils, and the rich indigo pigment often rubs off onto their skin, temporarily tinting it blue. This striking indigo attire, combined with the desert sun, leaves a bluish cast on faces and hands, a literal mark of their culture. The vivid blue clothing isn’t just for show; indigo dyes were a sign of wealth and prestige, and the Tuareg became famous for this iconic look across the Sahara.

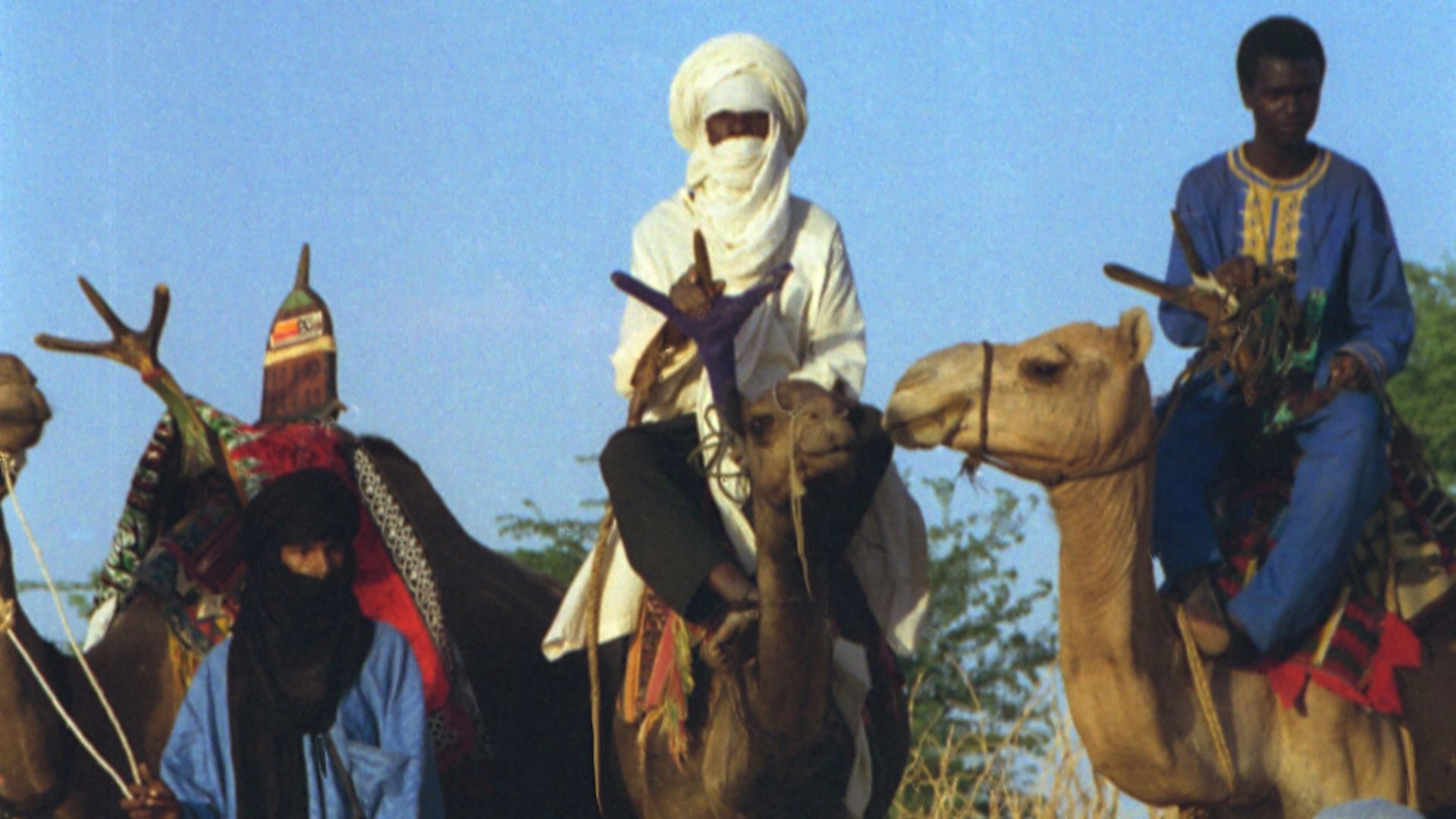

The Veiled People

One of the Tuareg’s own names for themselves is Kel Tagelmust, which literally means “the people of the veil”. This self-designation honors their iconic veil (the tagelmust), underlining how central the veiled male tradition is to Tuareg identity. They are also known as Kel Tamasheq, meaning “speakers of Tamasheq,” highlighting their shared language. Both names illustrate how the Tuareg define themselves by their cultural hallmarks, language and the ever-present face veil, rather than by any single country or territory.

Veiled Men, Unveiled Women

In a reversal of typical Islamic custom, Tuareg men—not women—are the ones who veil their faces. From adolescence, men put on the distinctive indigo-blue tagelmust, a combination turban and face veil, believed to ward off evil spirits and protect against desert sand. Taking on the veil is a proud rite of passage to manhood, and adult Tuareg males usually cover their face leaving only the eyes visible. By contrast, Tuareg women traditionally do not veil their faces.

Hocine Ziani, Wikimedia Commons

Hocine Ziani, Wikimedia Commons

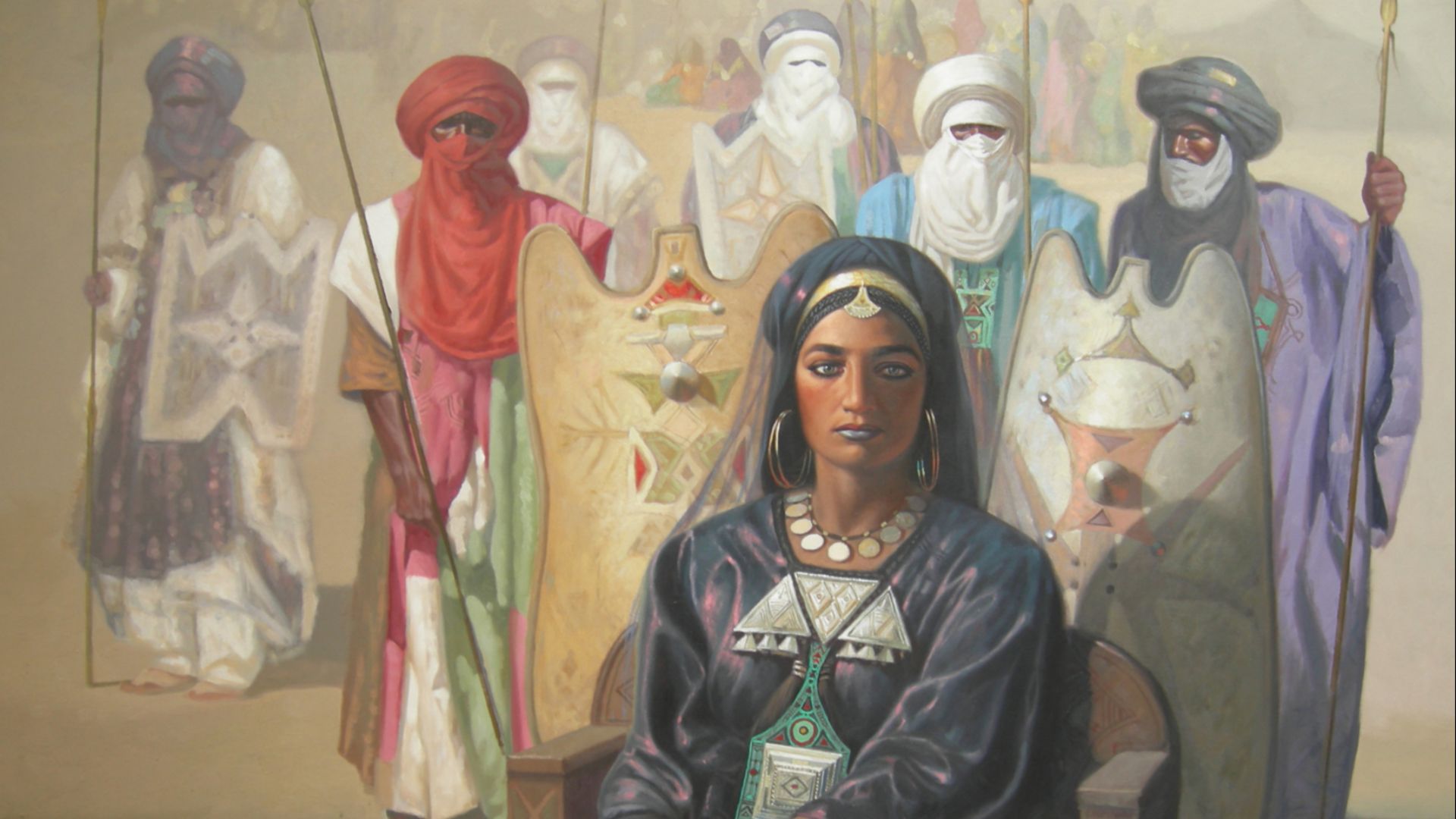

Matrilineal Legacy

Tuareg society has a strong matrilineal streak that sets it apart in the region. Family lineage and certain inheritances traditionally pass through the mother’s line, a practice that scholars say is a holdover from the Tuareg’s pre-Islamic past. Even leadership roles reflected this principle—for example, the title of amghar (chief) in a Tuareg clan was typically inherited by the chief’s sister’s son, rather than his own son. This emphasis on maternal kinship gave Tuareg women an influential position in community structure.

Patrick DE WILDE, Getty Images

Patrick DE WILDE, Getty Images

What’s In A Name?

The origin of the name “Tuareg” has long puzzled historians. One theory links it to the Berber word Targa, the Tuareg name for the Fezzan region of Libya, meaning “channel”; Tuareg would then be the plural Twārəg, “people of Targa”. Another theory assumes it comes from an Arabic exonym: Tuwariq, plural of Tariqi, though its meaning is less clear. Either way, the term is an exonym (a name given by others). The Tuareg themselves historically did not use “Tuareg” to refer to their own people, and its exact meaning remains a subject of debate among scholars.

Alfred Weidinger from Vienna, Austria, Wikimedia Commons

Alfred Weidinger from Vienna, Austria, Wikimedia Commons

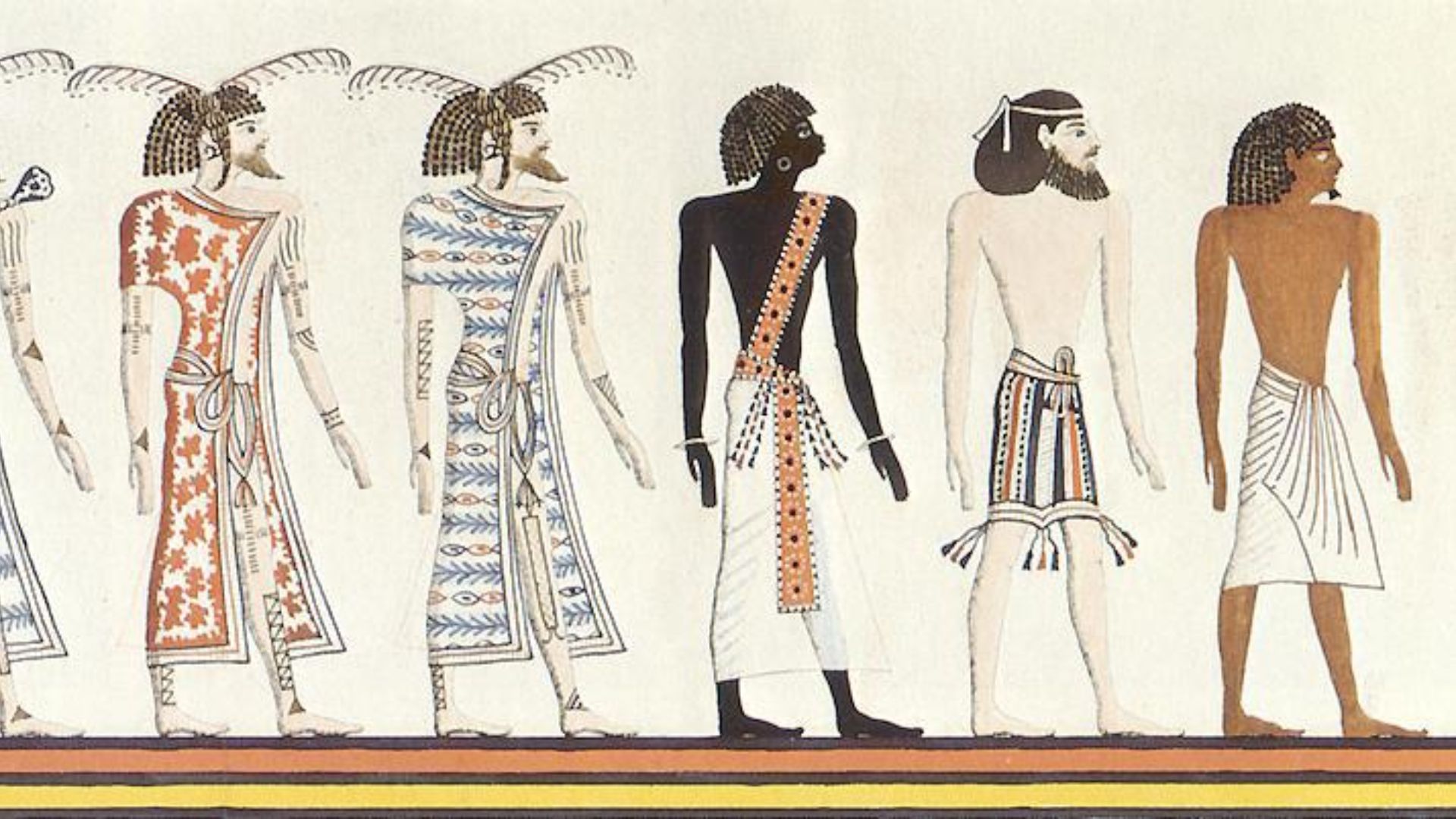

Tamasheq Tongue

The Tuareg speak their own set of closely related dialects collectively known as the Tuareg languages, or Tamasheq. These dialects are part of the Berber branch of the Afroasiatic language family, linking the Tuareg to the broader Amazigh (Berber) world linguistically. Interestingly, what outsiders call “Tuareg” is known by different names in different regions: western Tuareg in Mali call their speech Tamasheq, those in Algeria and Libya say Tamahaq, and in Niger (Aïr and Azawagh regions) they use Tamajeq.

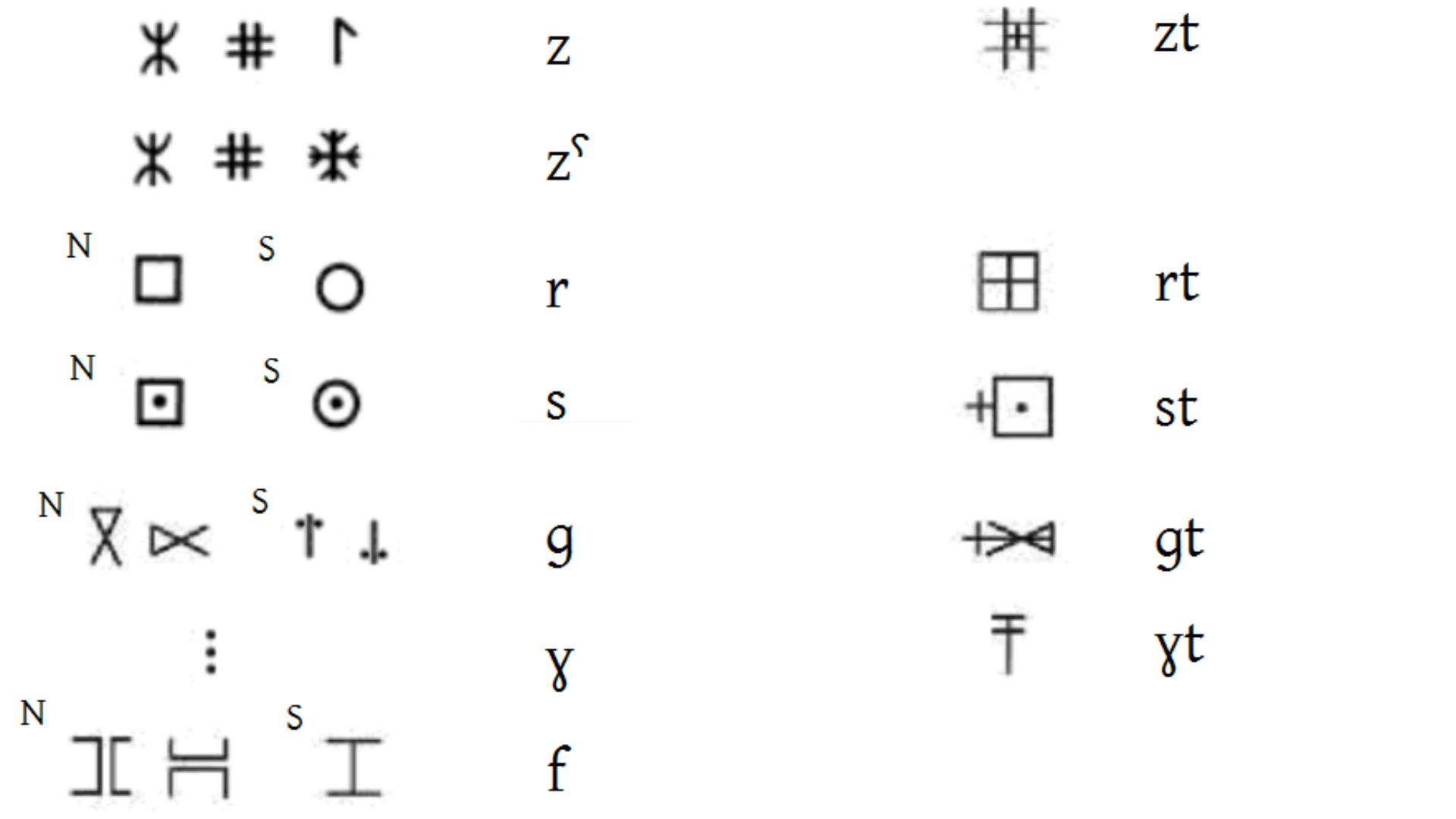

Ancient Alphabet

Remarkably, the Tuareg have preserved an ancient writing system that dates back to the earliest Berber civilizations. They still use Tifinagh, a traditional Berber alphabet, for inscriptions and symbolic purposes. In fact, a striking archaeological discovery in 1926, south of Casablanca, uncovered funerary texts in Tifinagh on a tomb, evidence that this script has been in use since antiquity. Tuareg craftspeople and youth groups today often pride themselves on using Tifinagh letters, helping keep this link to their ancient Saharan ancestors alive.

User:Kwamikagami, Wikimedia Commons

User:Kwamikagami, Wikimedia Commons

Pre-Islamic Roots

Before adopting Islam, the Tuareg followed traditional Berber spiritual practices. They believed in Berber mythology and funerary customs that included painting skeletal remains with ochre, a ritual known among North Africa’s prehistoric cultures. These practices likely descended from the Capsian culture that dominated the Sahara thousands of years ago. The Tuareg also built megalithic tombs (such as the jedar monuments), reflecting a complex pre-Islamic belief system. Traces of these ancient customs endure in Tuareg folklore and cultural rituals, even after centuries of Islamic influence.

W. Robrecht, Wikimedia Commons

W. Robrecht, Wikimedia Commons

Blended Beliefs

Tuareg religious life today is a unique blend of Islam and older customs. They overwhelmingly practice Islam (mostly the Maliki school of Sunni), but many pre-Islamic traditions have been woven into their day-to-day faith. For example, close-cousin marriages and even polygamy were adopted under Islamic influence, supplanting a previously monogamous culture. At the same time, Tuareg still cherish practices like using protective amulets and honoring matrilineal inheritance, cultural traces from pre-Islamic times that sit alongside Quranic observance.

Stratified Society

Traditional Tuareg society was highly stratified, with a strict social hierarchy that persisted into the 20th century. At the top were the nobles (Imajaghan), the warriors, and chieftains who led the camel raids and held political power. Below them were vassal groups and Islamic clerics (ineslimen, sometimes marabouts), followed by artisan castes like blacksmiths (Inadan) who were socially lower but essential for their skills. At the bottom were the unfree classes and their descendants. This caste-like system meant each Tuareg was born into a defined social status.

George Francis Lyon, Wikimedia Commons

George Francis Lyon, Wikimedia Commons

Forge Masters

The Tuareg’s distinctive handicrafts owe much to the Inadan, a hereditary caste of blacksmiths and artisans. The Inadan (also called enan) are the makers of combat equipment, tools, and jewelry, revered and a bit feared for their craft which was seen as semi-magical. Using skills passed down through generations, they forge the elegant straight swords known as takoba, fashion delicate earrings (tizabaten), cast the famous tanaghilt or Agadez Cross pendants, and craft many other items like daggers and camel saddle ornaments. Tuareg blacksmiths traditionally work in silver, iron, and brass, often employing the ancient lost-wax casting method to create intricate designs, providing everything from tools to symbols of identity.

Cross Of Agadez

One of the most famous symbols of Tuareg culture is the Cross of Agadez (tanaghilt or zakkat). This jewelry piece, typically worn as a pendant, comes in various stylized shapes that may resemble a cross, a plate, or a shield. Historically, the oldest Agadez crosses were made of stone or copper, but Tuareg artisans later crafted them from iron and silver using lost-wax casting. It has even come to represent Tuareg identity and political rights in modern times, being adopted as a pan-Tuareg emblem in Niger and beyond.

Protective Talismans

Tuareg jewelry often doubles as spiritual protection. Blacksmiths (Inadan) traditionally adorn metal pieces with engraved geometric patterns or even Quranic verses, believing these designs can ward off harm. Both men and women commonly wear amulets like the grigri, a small leather pouch containing sacred objects or verses, as a shield against evil. Tuareg lore also assigns meaning to materials: silver is thought to bring happiness, certain rare agates are believed to have healing powers, and a simple triangle shape is considered a protection against evil. Conversely, gold is seen as bad luck and thus avoided, which is why Tuareg jewelers historically favored coins and silver as their medium.

tuareg jewelry / silver bangle, IMPERIALS Yasufuku

tuareg jewelry / silver bangle, IMPERIALS Yasufuku

Desert Stargazers

Beneath the crystal-clear skies of the Sahara, the Tuareg developed a deep, practical intimacy with the stars. In their Tamasheq tongue, constellations bear poetic names: Venus is Azzag Willi—“the one that signals time to milk the goats”—while Orion’s Belt becomes Amanar, “the warrior of the desert”. The Pleiades are Shet Ahad (“seven sisters of the night”), and Ursa Major and Minor are known as Talemt and Awara, the waking she-camel and sleeping baby camel. These celestial names reveal just how closely Tuareg life flows with the rhythms of nature—guided by the stars like a cosmic compass.

Dominik Angstwurm, Wikimedia Commons

Dominik Angstwurm, Wikimedia Commons

Clan Confederations

Tuareg political organization has traditionally been based on clans and confederations. A Tuareg clan (tawshet) is essentially a large family group, and several clans can unite under an elected paramount chief called an amenokal. Such a union forms a Kel (meaning “those of…”), a confederation named after a region or direction—for instance, Kel Dinnig means “those of the East” and Kel Ataram “those of the West”. Each clan within the confederation is led by its own chief (amghar), but the amenokal provides overall leadership, especially in times of conflict or migration. Tuareg identity is deeply tied to these clan affiliations, often more so than any national identity.

Dan Lundberg, Wikimedia Commons

Dan Lundberg, Wikimedia Commons

Ancestress Of All

According to Tuareg oral tradition, all clans descend from a single ancestral mother. This legend likely emerged after the 11th-century Arab invasions, when Tuareg groups like the Lemta and Zarawa were pushed south and splintered into seven major clans. By tracing their roots to one woman, the Tuareg affirm unity across clan lines, a symbolic reminder that, despite differences, they are one extended family. In the unforgiving Sahara, that shared lineage was more than myth—it was survival.

Desert Sultanate

In 1449, the Tuareg founded the Sultanate of Aïr, also known as the Sultanate of Agadez, deep in the Aïr Mountains of present-day Niger. This desert kingdom thrived as a center of trade and political power, linking North and West Africa through bustling caravan routes. Under their Amenokal rulers, Agadez blossomed into a city of commerce and Islamic culture. Its enduring architecture still bears witness to a time when Tuareg nomads became urban state-builders.

A Spark Of Reform

In the 18th century, Tuareg scholar Jibril ibn ‘Umar of the Aïr region sparked a wave of Islamic reform that spread far beyond Tuareg lands. His impassioned teachings on religious renewal and moral leadership deeply influenced his student, Usman dan Fodio, who later led a major Islamic movement in the early 1800s. That campaign established the Sokoto Caliphate, one of the largest Islamic empires in 19th-century Africa. It’s a striking example of how Tuareg intellectual influence reached not only across deserts, but deep into the political future of West Africa.

Paule Crampel, Wikimedia Commons

Paule Crampel, Wikimedia Commons

Lords Of The Sahara

For centuries, the Tuareg were the undisputed gatekeepers of the central Sahara, controlling trade routes that linked the Mediterranean to the Sahel. Their camel caravans hauled gold, salt, and dates across the dunes, while outsiders paid dearly for safe passage—or suffered the consequences. This dominance gave them serious political leverage, and during colonial and post-colonial conflicts, the Tuareg fiercely resisted intrusion. To European powers, they weren’t just nomads, they were sovereign desert lords with little tolerance for trespassers.

Holger Reineccius, Wikimedia Commons

Holger Reineccius, Wikimedia Commons

Partitioned Homeland

By the 1960s, colonial borders had carved the Tuareg homeland into pieces, scattering them across five modern states—Mali, Niger, Algeria, Libya, and Burkina Faso. Suddenly, these fiercely independent nomads were minorities under distant, unfamiliar governments. Harsh new policies restricted their movement and disrupted centuries-old migration routes, while drought and desertification pushed many toward cities and wage labor. The stage was set for rebellion: the desert people had been boxed in, and they weren’t going to stay quiet.

Alfred Weidinger from Vienna, Austria, Wikimedia Commons

Alfred Weidinger from Vienna, Austria, Wikimedia Commons

The 1960s Revolt

In 1963, just three years after Mali’s independence, Tuareg discontent exploded into armed rebellion in the Adrar N’Fughas mountains. Fed up with political neglect and southern domination, Tuareg fighters demanded autonomy—or even secession. The Malian army crushed the revolt brutally, driving many families to flee across borders in fear. Though the uprising was short-lived, it ignited a lasting message: the Tuareg would not be sidelined in their own lands.

Fight For Azawad

By the 1990s, Tuareg unrest surged again across the Sahara. Armed rebellions erupted in both Mali and Niger, with fighters in Mali’s Kidal and Gao regions declaring Azawad as their homeland, while those in Niger’s Aïr Mountains and Ténéré desert demanded rights and recognition. Some movements even proclaimed full independence. Hundreds lost their lives, including prominent leader Mano Dayak, and thousands were displaced, pushing the “Tuareg question” into the international spotlight.

Peace And Strife

The rebellions of the 90s gave way to fragile peace. With France and Algeria mediating, Mali (1992) and Niger (1995) signed accords promising autonomy and army integration for Tuareg rebels. Many laid down arms, but the peace frayed quickly. Clashes resumed in Niger by the early 2000s, and by 2007, fresh fighting erupted, culminating in another major rebellion in Mali in 2012. For the Tuareg, peace has always come with an asterisk.

Rebirth Of Identity

While political battles raged, a cultural awakening quietly took hold. In the 1990s, the Amazigh movement reignited pride in Tuareg language and heritage, long suppressed by state policies. Since 1998, several pan-Tuareg flags have flown at festivals and protests, symbols of a united desert identity. Tamasheq music and poetry blossomed, with Tuareg bands gaining global recognition. This cultural renaissance became its own kind of resistance, less about secession, more about self-definition.

KENZO TRIBOUILLARD, Getty Images

KENZO TRIBOUILLARD, Getty Images

Marginalized In The Sahel

Despite their storied past, many Tuareg remain sidelined in the modern Sahel. In Niger, Tuareg communities face chronic underrepresentation, underdevelopment, and recurring poverty, worsened by droughts and shrinking pasturelands. In 2021, tragedy struck when militants massacred 141 people—mostly Tuareg villagers—in Tahoua, underscoring their vulnerability in today’s volatile Sahel. While some Tuareg have risen in politics or business, many still feel like outsiders in the very lands their ancestors once ruled.

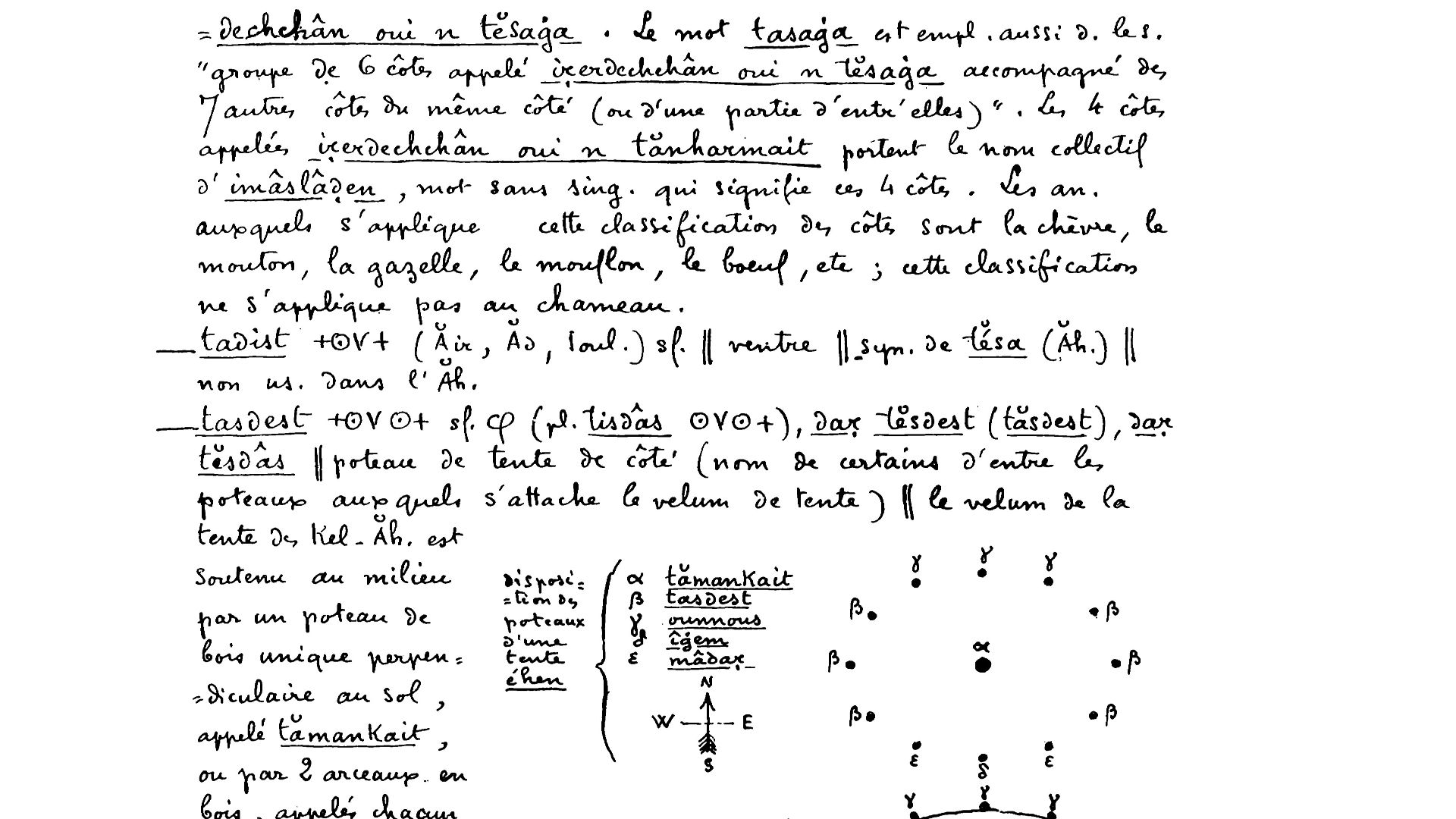

Married In A Tent

In Tuareg culture, marriage begins with a tent—literally. A new tent is built when a woman marries, becoming her property and the center of the household. If the marriage ends, she keeps the tent, giving Tuareg women a rare measure of security and autonomy. As life becomes more sedentary, houses may replace tents, but one saying still rings true: a Tuareg man rests best in the shade of his wife’s tent.

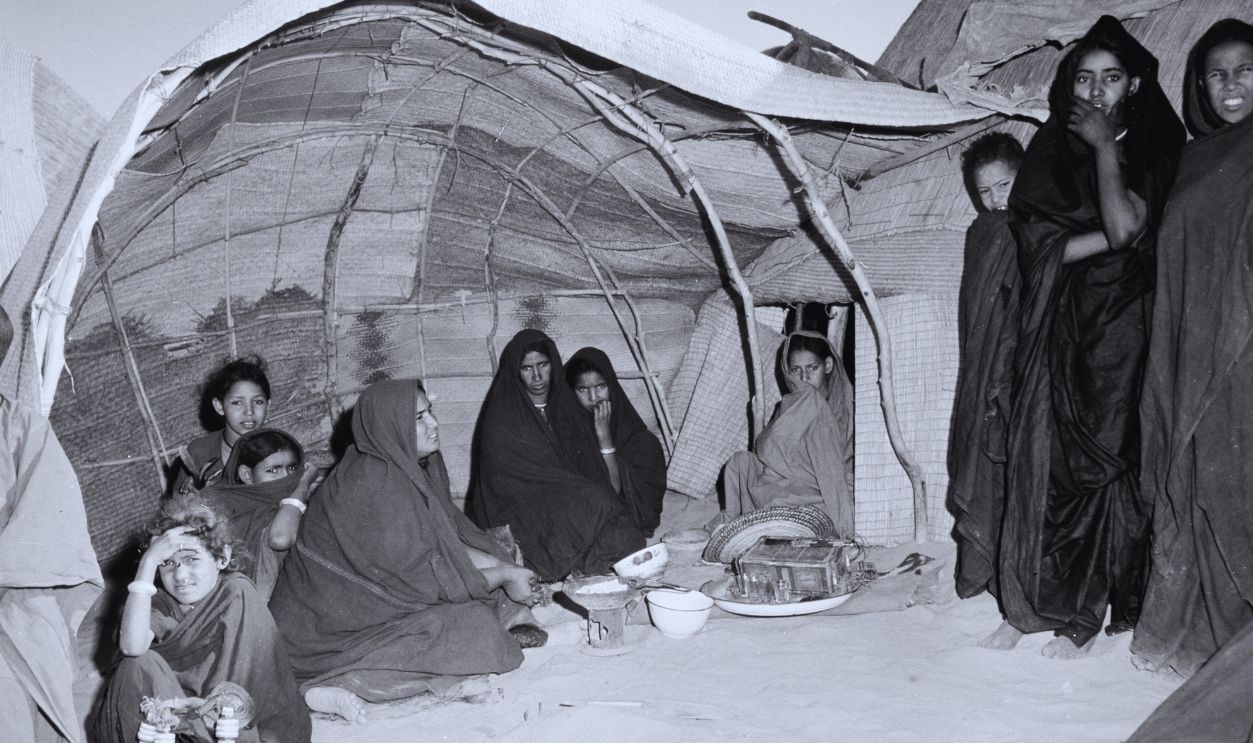

Homes On The Move

Tuareg architecture is built for mobility, from their classic tents of goatskin or woven mats to red ahaket shelters and millet-stalk shade canopies. Styles vary by tribe, but every design reflects their desert adaptability. Even settled Tuareg sometimes pitch a tent beside their homes—a quiet nod to their nomadic roots. As their legends tell it, they once nested in trees and caves before learning to build on the open ground, a journey reflected in every pole and panel they carry.

Sand-Baked Bread

Desert cuisine demands creativity, and the Tuareg have mastered it. Their signature flatbread, taguella, is baked directly in the sand beneath hot coals, producing a dense, nourishing loaf typically eaten with meat or savory sauce. Millet porridge (cink or liwa), camel or goat milk, and tangy goat cheese round out their staple foods. With just grain, milk, and dates, Tuareg meals are high-energy and perfectly adapted for survival on the move.

Dorine TAHON, Wikimedia Commons

Dorine TAHON, Wikimedia Commons

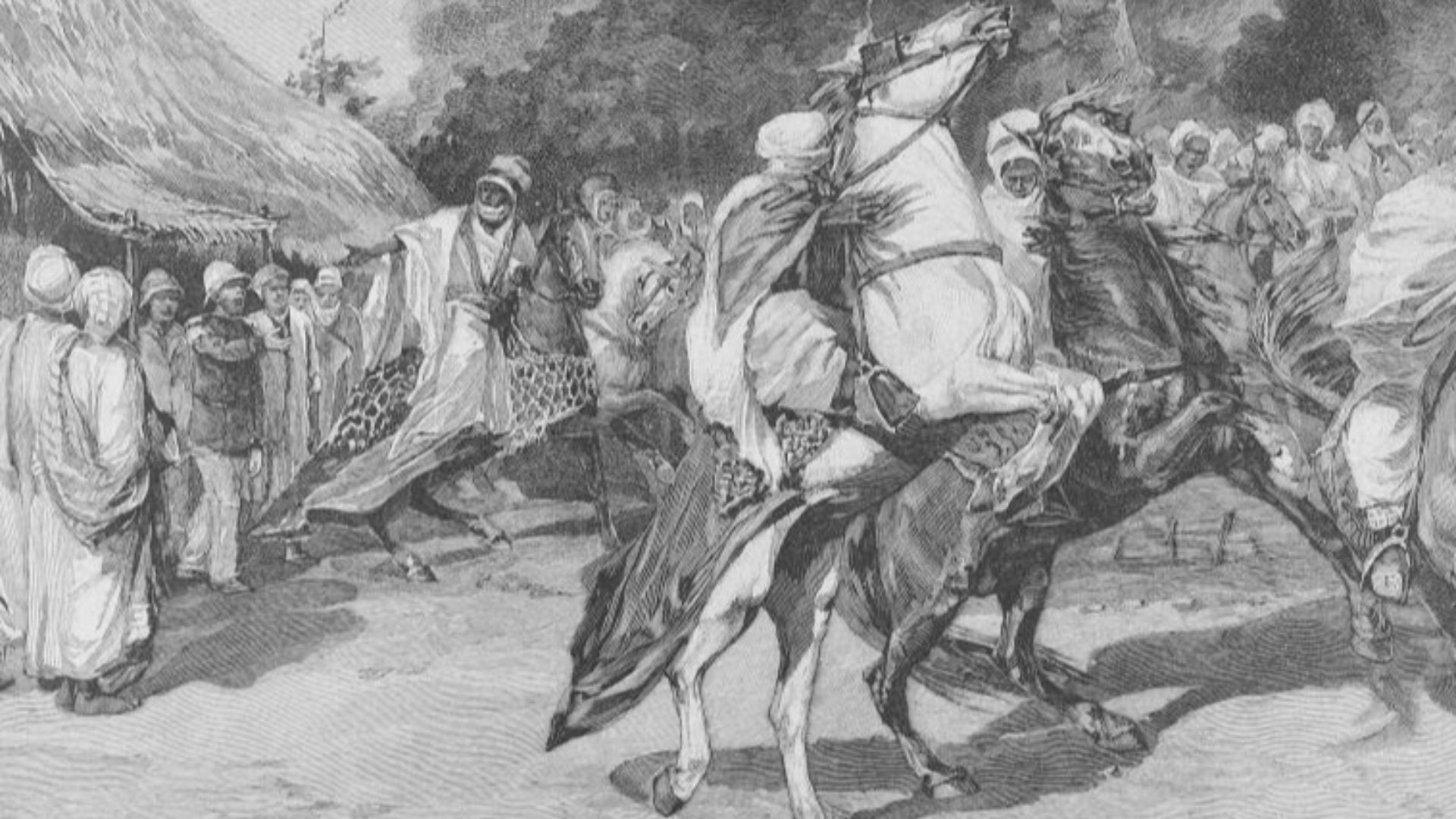

Spears And Swords

Tuareg warriors carved out a fierce reputation with their signature armaments: long spears, leather shields, and the iconic takoba sword, a double-edged blade often carried by nobles. The telek, a forearm dagger, added to their arsenal, while chainmail and iron helmets came via trade. Known for swift camel raids, Tuareg fighters struck fast across the dunes. One 1821 French sketch captured it perfectly: armed Tuareg warriors, veiled in blue, riding like thunder through the sands.

Veronique DURRUTY, Getty Images

Veronique DURRUTY, Getty Images

A Genetic Mosaic

Tuareg ancestry is anything but simple, it’s a rich genetic mosaic shaped by millennia of movement and mixing. Studies show they descend largely from ancient North African groups like the Taforalt people, with additional influences from the Middle East, sub-Saharan Africa, and even early European farmers. Much of this diversity predates the Arab conquests. Far from isolated, the Tuareg are the living legacy of a Sahara that was once a bustling corridor between continents.

Ghosts Of Garamantes

One intriguing theory links the Tuareg to the ancient Garamantes, a desert civilization that thrived in Libya’s Fezzan region from 1000 BC to the 5th century AD. When the Garamantes faded from history, some believe their descendants migrated south and gradually became the Tuareg. The Tuareg’s own oral tradition supports this, claiming northern origins from Targa (Fezzan). While not universally accepted, the theory suggests the Tuareg may carry the cultural torch of a forgotten Saharan kingdom.

Desert Missionaries

By the 12th century, the Tuareg had fully embraced Islam, and became key agents in spreading it across the Sahel. As caravan traders, they carried more than salt and dates: they brought the Quran, built mosques, and helped establish Islamic schools in towns like Timbuktu and Agadez. Tuareg scholars and merchants played an unsung role in shaping West Africa’s Islamic landscape. Their veiled silhouettes weren’t just traders, they were teachers crossing the sands.

Dan Lundberg, Wikimedia Commons

Dan Lundberg, Wikimedia Commons

Bonded Servitude

Despite their fierce independence, Tuareg society historically included a deeply rooted system of hereditary slavery. Captives known as Ikelan were taken during raids or purchased in Saharan markets, then assigned roles like herding and household labor. Their children, called irewelen, inherited servile status for generations. Though formal slavery was abolished in the colonial era, its legacy lingers: terms like Bellah in Niger still mark communities of slave descent, revealing the complex, and often uncomfortable, layers of Tuareg social history.

Jan Broekhuijse, Wikimedia Commons

Jan Broekhuijse, Wikimedia Commons

Desert Pastimes

Life in the Sahara isn’t all hardship, the Tuareg know how to play. From Tabillant wrestling to Tammazaga camel races, games test strength and speed while bonding the community. Kids play tag-like “jackal” games and laugh at Abarad Iqquran, a wooden puppet who tells ridiculous tales. These pastimes aren’t just fun, they’re practical training in disguise, passing on survival skills through tradition and play.

Vincent van Zeijst, Wikimedia Commons

Vincent van Zeijst, Wikimedia Commons

“Freemen” Of The Desert

The Tuareg call themselves Amajagh—“freemen”—a title steeped in pride and social nuance. Historically, the label applied to noble warrior lineages, excluding artisans and the servile class. So when Tuareg spoke of being “free,” it often meant freedom from subjugation—within a system that wasn’t truly equal. It’s a powerful identity, but one layered with hierarchy.

Hamdanmourad, Wikimedia Commons

Hamdanmourad, Wikimedia Commons

Desert Poetry

The Tuareg are masters of oral verse, crafting poetic laments, riddles, and love songs under the stars. Women and men alike recite tindi poems, often sung to the melancholy sound of the imzad fiddle. In the late 1800s, Charles de Foucauld was so enchanted that he compiled one of the first Tuareg dictionaries, filled with translated poems. Their verses weave metaphor and emotion into the very rhythm of Saharan life.

Men Adorned In Silver

In Tuareg culture, silver shines on everyone. Men wear necklaces, rings, and heirloom pendants, just as proudly as women, signaling status, identity, or protection. The famed grigri amulet—often containing Quranic verses—is worn by both sexes, while items like eweki armlets are reserved for men. Passed down through generations, Tuareg jewelry isn’t just decoration, it’s legacy, symbolism, and desert elegance wrapped into one.

You May Also Like:

The Dark Traditional Practices Of The Zulu People

Meet The African Tribe With An Otherworldy Connection

Photos Of The Fearsome Nomadic Tribe Roaming Kenya

San Francisco Chronicle, Hearst Newspapers, Getty Images

San Francisco Chronicle, Hearst Newspapers, Getty Images

Source: 1