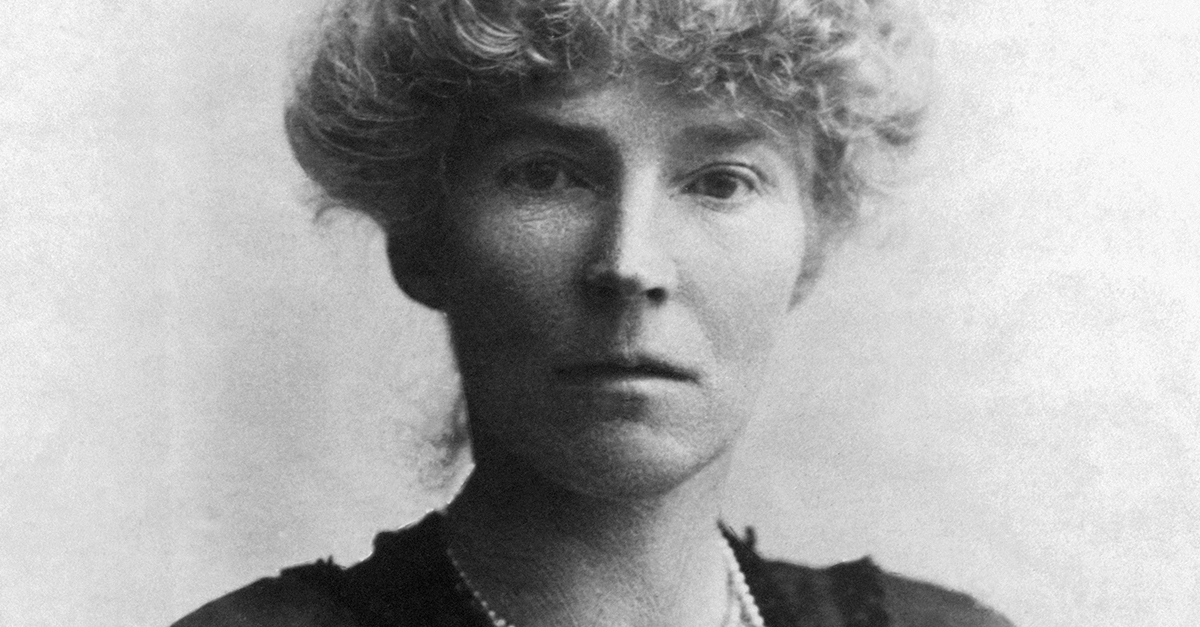

Search For Identity

In 2003, a marble head, broken off a larger statue, was unearthed at the ancient site of Chersonesus in Crimea near modern-day Sevastopol. For two decades its identity flummoxed the world’s best researchers. Now, after using new scientific methods, scholars are certain the statue depicts Laodice, a Roman‑era matron who played a key role in her city’s survival. The find reshapes our understanding of Black Sea urban life.

The Original Discovery In 2003

Archaeologists digging Chersonesus hauled up the marble head among rubble near a ruined public structure. The classical features, including finely carved hair, draped cloak lines, etc., marked it as high‑status. At the time, there was no inscription or accompanying statue remaining close at hand. For years, the portrait remained anonymous, a beautiful but mysterious artifact of days long gone.

Why The Identity Stayed Unknown

Without inscriptions or matching base fragments, the portrait didn’t give any direct clues. The region’s turbulent history included earthquakes, invasions, and oceanic erosion, leaving much of the statuary context in ruins. Even among experts, opinions were all over the map: goddess, noblewoman, unknown benefactor; nobody had a clue who she was. Until recently, she was just known as “the head from Chersonesus.”

Dmitry A. Mottl, Wikimedia Commons

Dmitry A. Mottl, Wikimedia Commons

New Research: What Changed?

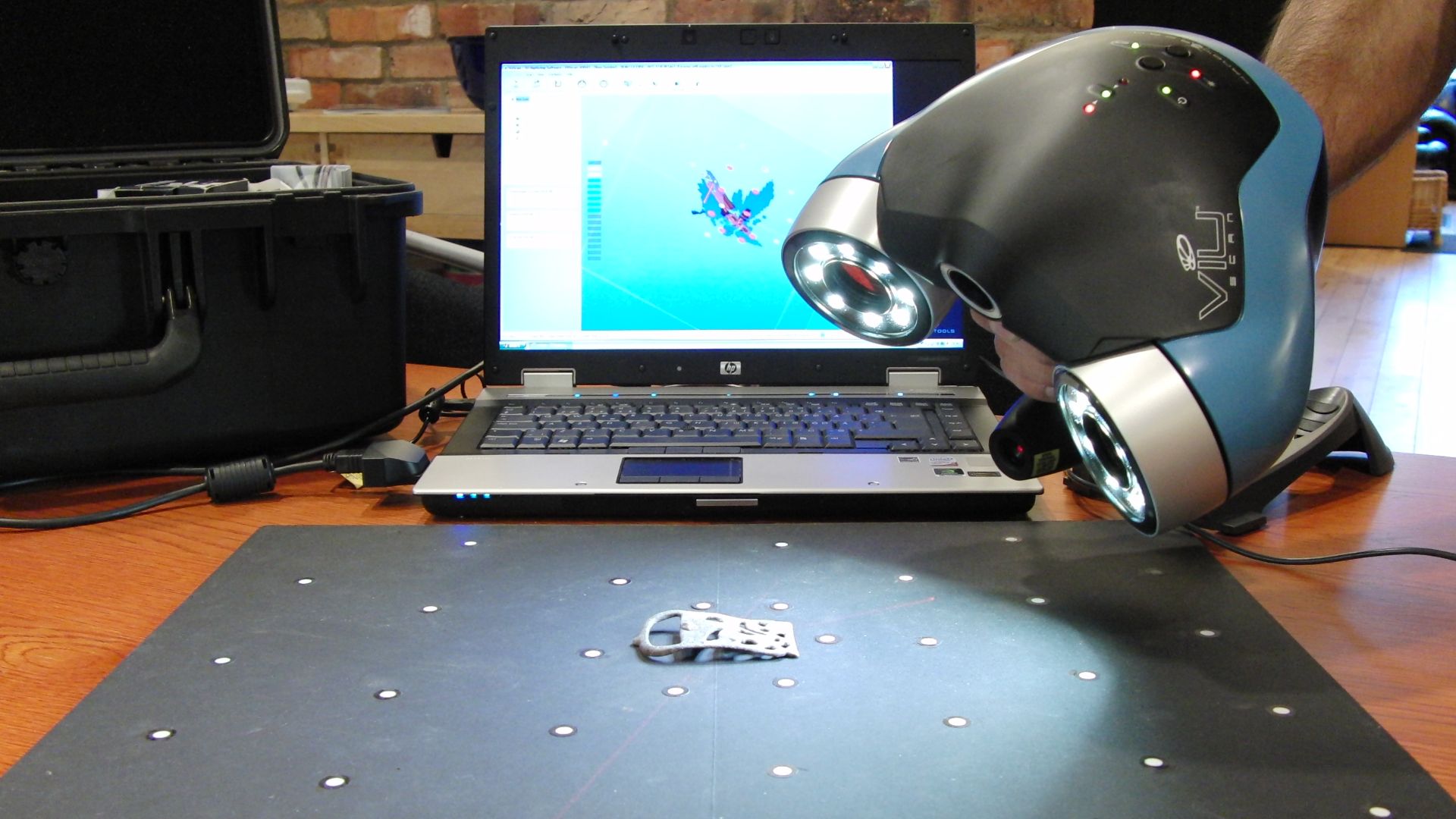

In 2025, a multidisciplinary team looked at the statue head again, this time with modern tools: 3D scanning, comparative stylistic analysis, and re‑examination of Byzantine and Roman‑era texts. They were searching for parallels in portraiture, clothing, and even the quarry that provided the raw marble. The resurgence in scrutiny finally yielded a strong candidate for the woman’s identity.

Creative Tools from Halmdstad, Sweden, Wikimedia Commons

Creative Tools from Halmdstad, Sweden, Wikimedia Commons

Comparative And Stylistic Clues

Scholars compared the head’s features with already known Roman matron portraits: hairstyle, drapery folds, and facial proportions, etc. The match was striking. Combined with regional art tradition, the portrait matched best with the known images of Laodice. The strong resemblance gave the researchers confidence in their conclusion.

Sources Point To Laodice

Historical texts make mention of a wealthy resident named Laodice who donated a large sum of money and land to Chersonesus in the early 2nd century AD, helping the city gain local autonomy from the Romans, including local administration, courts, minting of its own coins, and raising its own taxes. That she might be honored by a statue matches Roman local practices. The portrait could be the commemorative monument we were all hoping for.

Александра Кутлыярова, Wikimedia Commons

Александра Кутлыярова, Wikimedia Commons

Gender And Status

If the suppositions are correct, the statue is rare evidence of a prominent woman honored publicly in a Black Sea city on the frontier of the Roman Empire. That shatters our assumptions that public statuary was strictly reserved for men, including rulers, generals, and emperors. Laodice’s portrait shows that elite women could be celebrated for their contribution far from the tumultuous streets and back-alleys of Rome.

Mary Harrsch from Springfield, Oregon, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Mary Harrsch from Springfield, Oregon, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Chersonesus And Northern Black Sea Life

Chersonesus was a cosmopolitan port city on the northern Black Sea coast. Culturally, it was a melting pot of Greek, Roman, local, and trading cultures. The statue proves the city’s economic importance, civic pride, and cultural advancement long after its Greek founding. It’s a window into a bustling and dynamic frontier metropolis.

Chersonesus: Origins

Chersonesus was founded in the 6th century BC by Greek settlers looking to establish new trading colonies. Positioned on the southwestern coast of Crimea, it quickly grew into a city-state with strong agricultural and maritime economies. The fertile steppe lands around the peninsula provided grain, while the harbor connected Chersonesus to lucrative trade with the wider Greek world.

The Romans Arrived

Over the centuries, Chersonesus frequently clashed with neighboring Scythian tribes. It later fell under the influence of larger Hellenistic powers while still preserving a sense of autonomy. Public buildings, fortifications, and temples reflected its cultural wealth and Greek heritage. By the time the Romans arrived there, Chersonesus had stood for centuries as a resilient hub where Greek traditions blended with local customs.

Andrey Butko, Wikimedia Commons

Andrey Butko, Wikimedia Commons

Marble’s Origin: Tracing The Stone

Researchers carried out isotopic and mineralogical tests on the marble. The initial results suggest the stone came from a known imperial quarry in the Aegean region: the same source used for high‑status Roman monuments. This strongly implies that the statue was commissioned with the backing of considerable resources and status, rather than cheap local production materials and methods.

Rhoda Baer (Photographer), Wikimedia Commons

Rhoda Baer (Photographer), Wikimedia Commons

What The Marble Source Means

If the marble came from a high‑end imperial quarry, it tells us its subject, likely Laodice, had access to trade networks and wealth. It also shows that Chersonesus was internationally connected through far-flung trade routes, importing prestigious materials even to the empire's periphery. The long‑distance marble trade is even more definitive proof of the reach of Roman‑era commerce.

Anna Lobas, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Anna Lobas, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Artistic Quality And Craftsmanship

The carving is refined, with subtle facial structures, well‑draped cloak, detailed hair, natural proportions; these are the unmistakable hallmarks of high‑quality Roman‑period portrait sculpture. That craftsmanship supports the notion of a commissioned statue, dedicated for purposes of public admiration. It reflects high artisanal standards even in such a remote province as this.

Culture In The Black Sea Provinces

Statues like this suggest that Chersonesus and probably other cities in the region followed Roman practices of honoring private citizens, especially benefactors, with public monuments. It indicates the civic structures of patronage and gratitude, challenging our view of the Black Sea provinces as moribund and marginalized backwaters.

Evgeni Dinev @ Flickr, Wikimedia Commons

Evgeni Dinev @ Flickr, Wikimedia Commons

This Changes Our History Of Crimea

Crimea’s ancient history has often been told through Greek colonies, Byzantine holdovers, and later narratives from the Middle Ages. A confirmed Roman‑era statue of a named woman fills a big gap in the timeline. It’s convincing evidence of strong Roman civic identity in the region. It’s a big change to how we view Crimea’s place in antiquity.

Future Research Directions

Now that the head has had a positive identification, researchers are itching to search nearby soil layers and debris for remnants of the rest of the statue: the torso, the base, and the inscription. An inscription has been found that announced that a complete statue of Laodice was made in honor of her services, but the statue itself has yet to be located. If it is one day found, that could confirm the context. Unearthing the base would be amazing.

Galina Fomina, Wikimedia Commons

Galina Fomina, Wikimedia Commons

Other Anonymous Finds In The Region

The methods used here: stylistic match, historical cross‑referencing, marble sourcing, can all be applied to other anonymous statue fragments that people happen to dig up. These fragments are likely scattered across Crimea and the northern Black Sea coast. This could lead to re‑identification of multiple figures and a wholesale remapping of Roman‑era public art in the area.

Vyacheslav Argenberg, Wikimedia Commons

Vyacheslav Argenberg, Wikimedia Commons

Public Awareness And Heritage Conservation

The discovery drew international attention. It speaks to the need for careful conservation at Chersonesus and other ancient sites threatened by tourism, erosion, and looting. Highlighting this statue could galvanize international determination to protect sensitive heritage sites in Crimea and pretty much anywhere else.

The Story’s Human Dimension

Beyond archaeology, the statue connects us to the real people of the past; not emperors, but local citizens like Laodice who invested in their city’s survival. Ancient history doesn’t always have to be just about grand politics but also personal stories of generosity, community, and identity.

What The Portrait Reveals About Identity And Memory

Monuments like this show how Roman communities remembered and honored individuals centuries ago. The statue immortalizes Laodice’s name and her deeds. Its rediscovery and confirmation of identity revives these foggy memories, linking modern people to a past where civic pride, female agency, and local identity could thrive even under the watchful eye of one of history’s greatest empires.

Bridging Millennia

The marble head found at Chersonesus is a long-lost portrait of Laodice, a woman whose contributions shaped her city’s fate. Modern science, art history, and archaeological hard work has given her back her name. The discovery rewrites part of Crimea’s history and even more importantly, shows there’s a lot more riches to be hauled out of its fertile soil.

You May Also Like: