Last Stand In Florida

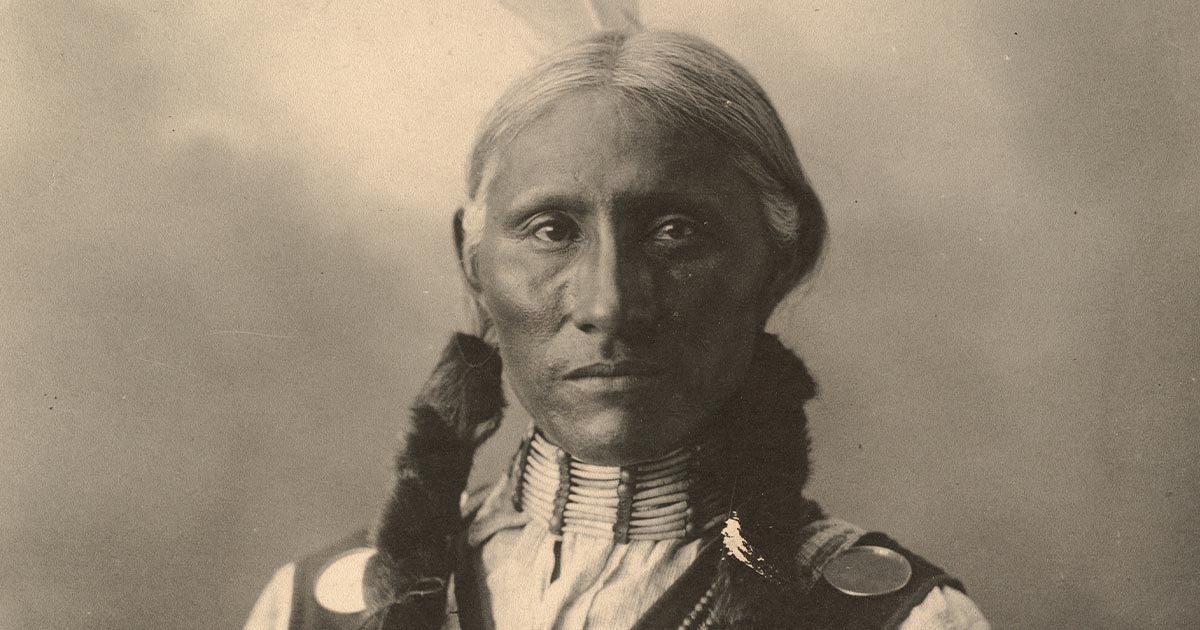

An Indigenous warrior with a murky past, Osceola fought in protracted battles against American attempts to expel Natives from Florida. But he was tricked and captured, dying behind bars. In the end, he was unable to stop the expulsions, but still made his mark in history.

Powerful Tribes

The Creek peoples play a major role in this story. They were a powerful confederacy of Indigenous tribes in the South, trading and dealing with colonial authorities, and eventually the US government. But ultimately, the Creeks were seen as an obstacle to white settlement.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Birth Of A Warrior

Osceola, first known as Billy Powell, was born around 1804. Childhood details are sketchy, but his birthplace seems to have been a Creek town called Talasi (Tallassee) in present-day Alabama. Osceola would always say he was Native, but the details get a bit complicated.

Metilsteiner, Wikimedia Commons

Metilsteiner, Wikimedia Commons

Mixed Heritage

Osceola’s mother was Polly Coppinger, who is believed to have had both European and Creek blood. This was hardly uncommon in Alabama, where settlers, traders, and Creek people had been in close quarters for decades. The question of Osceola’s father turns out to be a bit more contentious.

TradingCardsNPS, Wikimedia Commons

TradingCardsNPS, Wikimedia Commons

Trading Places

Many believe Osceola’s father was William Powell, a trader whose Scottish grandfather, James McQueen, was one of the first white settlers in the Talasi area. But some people theorize that Osceola’s father was Native, and Powell married Polly after the presumed father had passed away.

Henry Alexander Ogden (Harry Ogden), Wikimedia Commons

Henry Alexander Ogden (Harry Ogden), Wikimedia Commons

Wielding A Red Stick

But what’s not in dispute is that Osceola was born into conflict. Some Creeks didn’t trust the authorities and white settlers. Ironically, Osceola’s family seems to have been part of this Red Stick faction—and Peter McQueen, one of James’s sons, played a big role in the fighting.

Mason Jackson, Wikimedia Commons

Mason Jackson, Wikimedia Commons

Trip To Florida

Peter McQueen had joined the same clan as Polly’s, and helped lead the anti-settler faction. When the Creek War started in 1813, Florida was still controlled by the Spanish. Peter and other warriors snuck across the border and bought gunpowder and lead shot from traders there.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Crossing The Creek

Upon their return, they set fire to Creek plantations allied with the opposing side—who proceeded to ambush Peter McQueen’s warriors at the Battle of Burnt Corn Creek. But undaunted, he joined an attack on Fort Mims and participated in the Battle of Autossee.

John Rostron, Stubble burning in North Essex, Wikimedia Commons

John Rostron, Stubble burning in North Essex, Wikimedia Commons

Losing Ground

In between clan fighting and the power of the US Army, the Creek suffered massive setbacks and signed the Treaty of Fort Jackson in 1814. As a result, the Creek gave up much of their territory in Alabama and Georgia. Peter McQueen decided it was time to make an exit.

Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Due South

It’s not clear exactly when, but Peter McQueen led Osceola and family across the Florida border and settled in the Tallahassee area. They joined the Seminole tribes there, named after the word for “wild” in Muskogee. It was here that Billy Powell would soon receive his Native name.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

A New Era

The Seminole were a diverse group that included Creek clans and escaped slaves. Although eclectic, Seminoles still had their traditions, and so Billy Powell went through a coming-of-age ceremony that required downing a rather strong “black drink” known as “asi”.

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Internet Archive Book Images, Wikimedia Commons

Names To Watch

Participants in the “asi” ceremony would shout “Yaholo!”—and from these words came “Asi-Yaholo,” rendered in English as “Osceola”. But if a change of name marked a new era in Osceola’s life, an old name marked an ominous enemy of the Seminoles: Andrew Jackson.

Rembrandt Peale, Wikimedia Commons

Rembrandt Peale, Wikimedia Commons

A Grim Legacy

Andrew Jackson would become the seventh president of the United States in 1829 after decades of controversy. He owned a plantation worked by numerous African American slaves and had led the government’s side in the Creek War that had pushed Osceola into Florida.

Calvert Lith. & Engr. Co., Wikimedia Commons

Calvert Lith. & Engr. Co., Wikimedia Commons

Reckoning Time

Jackson had become a national hero in the Battle of New Orleans in 1815—and after defeating the British, he set his sights on other enemies. In 1817, Jackson led the First Seminole War to wreak revenge on Seminoles who’d supported the British or harbored escaped slaves.

U.S. Marine Corps, Wikimedia Commons

U.S. Marine Corps, Wikimedia Commons

Empire Strikes Out

By the time Osceola’s family had shown up in Florida, Spain was having a lot of trouble running the territory. Independence movements were flaring up throughout the imperial power’s grand empire, and Florida wasn’t a big priority. Quite simply, Spain was losing its grip on Florida.

Grabado:Creator:Jean-Nicolas Lerouge Dibujo:Creator:François Ligier, Wikimedia Commons

Grabado:Creator:Jean-Nicolas Lerouge Dibujo:Creator:François Ligier, Wikimedia Commons

Free-For-All

Plantation owners had raided Florida for years to recapture their slaves, while the British surreptitiously gave arms to the Seminoles to resist both Spanish and American forces. Jackson imposed a food blockade on Pensacola to hinder British use of the town during the War of 1812.

Urban~commonswiki, Wikimedia Commons

Urban~commonswiki, Wikimedia Commons

Adding To The Chaos

So once hostilities with the British ended in 1815, Jackson wanted to finish the Seminole problem and end the chaotic Spanish rule of Florida. And just as the British had trespassed on Spanish territory, the Americans would now do so—starting the first of three extended conflicts.

Ralph Eleaser Whiteside Earl, Wikimedia Commons

Ralph Eleaser Whiteside Earl, Wikimedia Commons

Stating The Obvious

In 1817, the US Army ordered Jackson to take charge of a mission to subdue the Seminoles. He and his men crossed the border and destroyed Seminole villages—and then occupied Pensacola. The Spanish expressed their outrage, but it was plain they’d already lost Florida.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Hasta Luego

Spain signed the Adams–Onis Treaty in 1819 and agreed to withdraw by 1821. The refuge that Florida had provided Osceola and his family was about to come to an end. American settlers flooded into the newly available territory, and they clearly wanted Seminole land.

Gilbert Stuart and Thomas Sully, Wikimedia Commons

Gilbert Stuart and Thomas Sully, Wikimedia Commons

Coastal Retreat

After losing battles, the Seminole signed the Treaty of Moultrie Creek in 1823, pushing them away from the coast and a lucrative sea trade. Osceola and his family moved south into the inhospitable wilds of central Florida. Then, another treaty brought Osceola into the spotlight.

The Nemesis Returns

Old enemy Andrew Jackson ran for president but failed to get an absolute majority in the Electoral College. The House of Representatives then chose John Quincy Adams. Undaunted, Jackson ran again in 1828. He won, and gained even more power to target Native Americans.

Ralph E. W. Earl, Wikimedia Commons

Ralph E. W. Earl, Wikimedia Commons

Mass Eviction

In 1830, Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, which mandated that any Natives east of the Mississippi would be moved west of the river. Authorities in Florida, a federal territory, now had the go-ahead to pressure or force the Indigenous population to leave for distant lands.

Karl Bodmer, Wikimedia Commons

Karl Bodmer, Wikimedia Commons

Another Bargain

As Florida turned unpleasant, some Seminole chiefs signed the Treaty of Payne’s Landing in 1832. In exchange for leaving Florida, their tribes would be given land west of the Mississippi River. Legend has it that Osceola disagreed, taking out his blade and stabbing the treaty.

Ferdinand Richardt, Wikimedia Commons

Ferdinand Richardt, Wikimedia Commons

Simmering Resentment

Five chiefs refused to sign, so the Americans’ local Indigenous agent, Wiley Thompson, stripped the chiefs of their positions. He also banned the Seminoles from arming themselves. Osceola was furious, as he felt the ban felt too much like the prohibition on slaves similarly being armed.

Osceola - DEFA-Trailer, DEFA-Stiftung

Osceola - DEFA-Trailer, DEFA-Stiftung

A Gift To Remember

Curiously, Thompson still considered Osceola to be a friend and gave him a rifle. Osceola would often get upset at Thompson, storming into his office and yelling at him. Finally, Thompson sent him to Fort King’s brig and told him to be more respectful—and specified how.

Sign Of Trouble

Thompson demanded that Osceola agree to leave Florida by signing the Treaty of Payne’s Landing. Osceola would also have to bring his followers into the fort. Faced with the ultimatum, Osceola signed the treaty, but he was seething from this humiliation. So, he planned his revenge.

Osceola - DEFA-Trailer, DEFA-Stiftung

Osceola - DEFA-Trailer, DEFA-Stiftung

A Seminole Moment

Osceola would have one last encounter with Thompson. He walked up to the Indigenous agent and shot him with the very same rifle Thompson had given him. Then, Osceola and his followers shot six people outside Fort King, while other Seminoles ambushed the US Army marching to the fort.

Charleston, S.C. : T.F. Gray and James, Wikimedia Commons

Charleston, S.C. : T.F. Gray and James, Wikimedia Commons

Many Enemies

In what the Americans called the Dade Massacre, the Seminole party took the lives of over 100 infantrymen. As 1835 ended, the Second Seminole War started. And vengeance ranged wide. Not only did Osceola attack white settlers, but he also sought to punish Natives who’d cooperated with them.

Final Sale

Just a month before, Osceola had punished Seminole Chief Charley Emathla, who’d just finished selling his cattle before heading west. As the chief made his way back to his village, Osceola dispatched him and flung the money from the cattle sale over the chief’s body.

User:SEWilco, Wikimedia Commons

User:SEWilco, Wikimedia Commons

Bloody Toll

Fighting would be fierce and bloody. By the time this latest series of conflicts ended in 1842, the US Army had lost three men for every four Seminoles it had captured, but Osceola would not live to see the end of the conflict—even though his tactics and forces had frustrated the enemy.

User:SEWilco, Wikimedia Commons

User:SEWilco, Wikimedia Commons

Truce And Consequences

Repeated setbacks prompted Jackson and his forces to come up with a new strategy. Osceola was lured to his fate in 1837, when the Americans called a truce to hold negotiations. But instead, they took Osceola captive. White settlers were relieved, but much of the public disapproved.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Farewell To Florida

Osceola was imprisoned at Fort Marion in St Augustine. Two months later, around 20 Seminole warriors escaped, but Osceola was too sick to climb the walls of his cell and join them. His captors then transferred him to Fort Moultrie in South Carolina, far from hostile Florida.

Samuel A. Cooley, Wikimedia Commons

Samuel A. Cooley, Wikimedia Commons

Portrait Of A Warrior

In his final weeks, Osceola put on a full range of Native attire so George Catlin, an artist fascinated by Indigenous culture, could paint a portrait of him. But Osceola’s health continued to decline, and he took his last breath on January 30, 1838. Yet Osceola would not rest in peace.

Final Indignity

Osceola was buried on the grounds of Fort Moultrie—or, at least most of him was. Osceola had asked his doctor, Frederick Weedon, to make sure his body was returned to Florida. Instead, Weedon surreptitiously cut off the head of Osceola’s body, and displayed it in his drugstore.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Museum Piece

And that’s not the only place it turned up. Weeton would place the head in his sons’ bedroom when he needed to frighten them into obedience. Eventually, a surgeon, Dr Daniel Whitehurst, added the head to his Surgical and Pathological Museum, which burned down in 1866.

Osceola - DEFA-Trailer, DEFA-Stiftung

Osceola - DEFA-Trailer, DEFA-Stiftung

Osceola’s Family

Osceola had two wives, one of whom was Black, and had five or more children. There’s an anonymous painter’s “Sedgeford Hall Portrait” that shows his wife Pe-o-ka and their son. This portrait was long misidentified as depicting Pocahontas and her son, Thomas Rolfe.

Unidentified painter, Wikimedia Commons

Unidentified painter, Wikimedia Commons

Final Defeat

As for the Seminole people, thousands were moved to the Indigenous Territory before the Third Seminole War, which lasted from 1855 to 1858. After that, the only Seminole remaining in Florida were the few that had fled to the Everglades wetlands. Defeat had been almost total.

State Library and Archives of Florida, Wikimedia Commons

State Library and Archives of Florida, Wikimedia Commons

Hidden Away

But astonishingly, the few hundred Seminoles who’d escaped to the Everglades managed to carry on their traditions, staying mostly isolated until the 1930s, when the US government created a reservation. As farmers drained the wetlands, more Seminoles rejoined society.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Carrying On The Tradition

And Joe Dan Osceola, the great-great-great-grandson of the original Osceola, became chief of the Seminole Tribe of Florida in the 1960s. He passed on in 2019 at the age of 82. The Seminole have six reservations in the state and number about 17,000. And they’ve triumphed over the last few decades.

Pangaea Auctions Interview of Chief Joe Dan Osceola, One World One Connection (Pangaea Auctions)

Pangaea Auctions Interview of Chief Joe Dan Osceola, One World One Connection (Pangaea Auctions)

A Successful Gamble

The Florida Seminole tribe became one of the first tribal governments to run gambling operations that now earn over a billion dollars per year. In 2007, the Seminoles bought the Hard Rock Cafe company and most of its branded properties. The tribe’s net worth is around $12 billion.

State Library and Archives of Florida, Wikimedia Commons

State Library and Archives of Florida, Wikimedia Commons

Exile Community

Meanwhile, the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma is made up of many of the descendants of those who left Florida. It has around 19,000 members, of whom around 14,000 live in Oklahoma. The tribal government runs three casinos and other businesses, and manages a land-claims trust.

National Archives at College Park, Wikimedia Commons

National Archives at College Park, Wikimedia Commons

A President’s Legacy

Andrew Jackson managed to push many Indigenous peoples to the sidelines, including the Seminole, sometimes at great cost. He won a second term as president but remains a controversial figure in American history. The Seminole, meanwhile, continue to honor their warrior known as Osceola.

Unknown authorUnknown author or not provided, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author or not provided, Wikimedia Commons

You May Also Like:

Chief Pontiac’s Brutal Fight For Freedom

The Tale Of The Seminole: Florida's Unconquered Tribe

The Horrific Discovery On Andrew Jackson’s Tennessee Plantation

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19