The Curse Of King Tut's Tomb

When Howard Carter cracked open King Tutankhamun’s tomb a century ago, he didn’t just uncover a long-lost pharaoh—he unleashed Tutmania. The world went wild for ancient Egypt overnight, and modern Egyptology was born in a blaze of gold, sand, and superstition.

But amid the wonder came whispers of something darker. One by one, people connected to the discovery began to fall ill—or worse. Was it coincidence, or had they awakened a curse that was better left buried?

Not The Only Curse Out There

The King Tut incident wasn’t the first time that stories spread about a cursed tomb. Although rarer than the gossip would suggest, there were in fact some Egyptian tombs that contained warnings about potential curses.

These types of warnings were the exception, though—as the mere idea of disturbing a tomb, especially one belonging to a ruler, was unimaginable.

Strange Occurrences

Of course, that didn’t stop strange stories from spreading. In one incident, a cobra—one of the most prominent symbols of Ancient Egypt—was found in Carter’s home, having ingested his pet canary, soon after they worked on opening the tomb.

And things only got worse once they actually entered it.

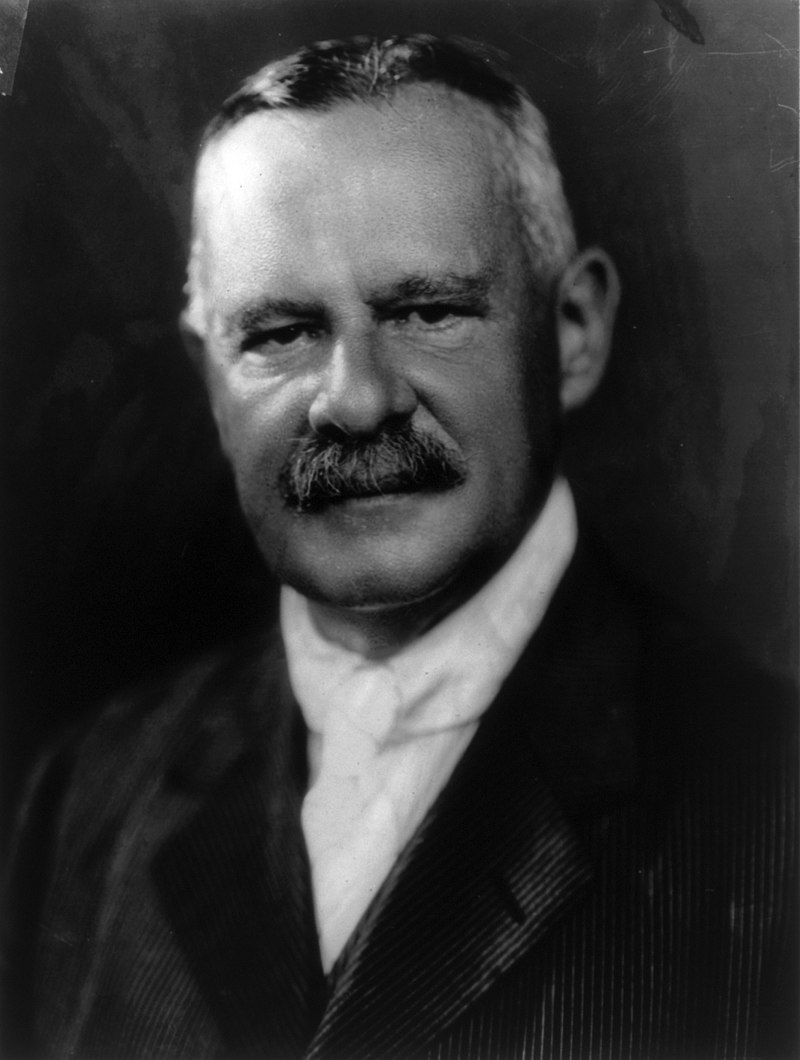

Howard Carter

Howard Carter

The First Victim

In April of 1923, the excavation’s financier, Lord Carnarvon, succumbed to blood poisoning after nicking a mosquito bite while shaving. Immediately, the news caused a sensation among media outlets, which began to spread stories about the tomb’s curse.

Many got in on the action, including Sherlock Holmes creator Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

Harry Burton, Wikimedia Commons

Harry Burton, Wikimedia Commons

The Elementals

Doyle supported the existence of the tomb’s curse and claimed that elemental spirits were responsible for Lord Carnarvon’s untimely demise. According to Doyle’s theory, the elementals had been summoned by King Tut’s priests to guard his tomb.

Doyle’s comments stoked the media frenzy—and so did the misfortunes of Sir Bruce Ingham, the second victim of King Tut’s curse.

Bain News Service, Wikimedia Commons

Bain News Service, Wikimedia Commons

The Lucky One

As far as victims of King Tut’s so-called curse go, Sir Bruce Ingham got off easy—though “easy” is relative. A close friend of Howard Carter, Ingham received a bizarre gift from the famed archaeologist after the tomb’s discovery: a paperweight fashioned from a mummified hand.

It wasn’t long before Ingham’s luck began to unravel. His house mysteriously burned down, and when he tried to rebuild, a flood destroyed the new one. He may not have met the same fate as other alleged victims, but fate clearly had a bone to pick with him—quite literally.

Double Trouble

Soon after receiving the mysterious paperweight, Ingham’s house burnt down. He managed to rebuild it but the curse wasn’t done with him—in the middle of the reconstruction, his house was hit by a flood.

Ingham ended up giving the paperweight away, which perhaps saved him from a worse fate. Unfortunately, the same cannot be said of others who ventured into King Tut’s tomb.

The Curse Strikes Again

Another supposed victim of King Tut’s curse was an American financier, George Jay Gould. Gould wanted to see King Tut’s tomb for himself, and he did just that—only to fall sick with a fever three days later.

Gould never recovered and perished a few months later, in May 1923.

The Frenzy Continues

The media frenzy around the curse was reignited in 1924, after the passing of archaeologist Hugh Evelyn-White. Evelyn-White had worked on the excavation and took his own life a year later. It seemed like it had nothing to do with the curse…

Until the archaeologist’s last letter was found. It read: “I have succumbed to a curse.”

Apparently, so did the man who dared to X-ray King Tut’s mummy.

A Deadly Picture

It wasn’t only the financiers and excavators who suffered the perils of the tomb’s curse. In 1924, radiologist Sir Archibald Douglas Reid performed an X-ray on King Tut’s mummy before it was so be sent to the museum.

The next day, the radiologist fell ill. Three days later, he was dead.

But Is The Curse Real?

Despite the eerie string of deaths linked to King Tut’s tomb, plenty of skeptics have rolled their eyes at the idea of a curse. Even Howard Carter himself wasn’t convinced—he lived for years after the discovery, ultimately dying of cancer at a respectable age. In fact, many who stepped foot inside the tomb went on to enjoy long, uneventful lives, which makes the “curse” sound more like superstition than supernatural vengeance.

But modern science has a way of spoiling a good ghost story—and in this case, it might have uncovered what really haunted King Tut’s tomb.

The Science Behind The Curse

It turns out that ancient Egyptian tombs are the perfect breeding ground for fungus. The spores from the fungus can cause deadly infections after prolonged exposure or in people who have weak immune systems.

In the case of Lord Carnarvon, for example, the fungus could have entered his bloodstream when he cut himself with his razor. George Jay Gould and Sir Archibald Douglas Reid could also have been infected, as the symptoms they exhibited before they perished are similar to an allergic reaction to the mold.

Final Thoughts

The theory of mold is a strong one, but there’s still no conclusive evidence to suggest that it led to the deaths of those who entered King Tut’s tomb. There’s also no evidence that anything in Tut’s tomb, supernatural or otherwise, caused these deaths.

There was never a warning of any kind inscribed on King Tut’s tomb, but stories of the curse have persisted over the years, speaking to the world’s enduring fascination with the curse of this mummy.

Source: 1