America’s Deepest Wildcard

What happens when the ground beneath a national park holds enough power to rewrite the country? If a supervolcano snapped awake, ash could smother regions and disrupt everything people rely on.

Where Yellowstone Sits

Yellowstone sits mostly in Wyoming, with stretches reaching Idaho and Montana. Scientists at the Yellowstone Volcano Observatory, led by USGS geophysicist Dr Mike Poland, monitor the region’s heat, geysers, earthquakes, and shifting ground to track the enormous magma reservoir beneath the park.

Dietmar Rabich, Wikimedia Commons

Dietmar Rabich, Wikimedia Commons

How Scientists Found It

They first recognized Yellowstone’s volcanic roots by studying its unusual geology. The bubbling hot springs and dramatic geysers helped scientists realize the park sits over an active heat source. These clues eventually revealed something far larger and more dangerous than a typical volcano hiding beneath the surface.

Brocken Inaglory edited by Muhammad, Wikimedia Commons

Brocken Inaglory edited by Muhammad, Wikimedia Commons

A Very Long History

Yellowstone’s volcanic history stretches back millions of years, yet the three biggest eruptions occurred within the last two million years. That pattern led experts to investigate whether future activity might repeat. They prompt detailed studies into the region’s past eruptions and long-term behavior.

U.S. Geological Survey from Reston, VA, USA, Wikimedia Commons

U.S. Geological Survey from Reston, VA, USA, Wikimedia Commons

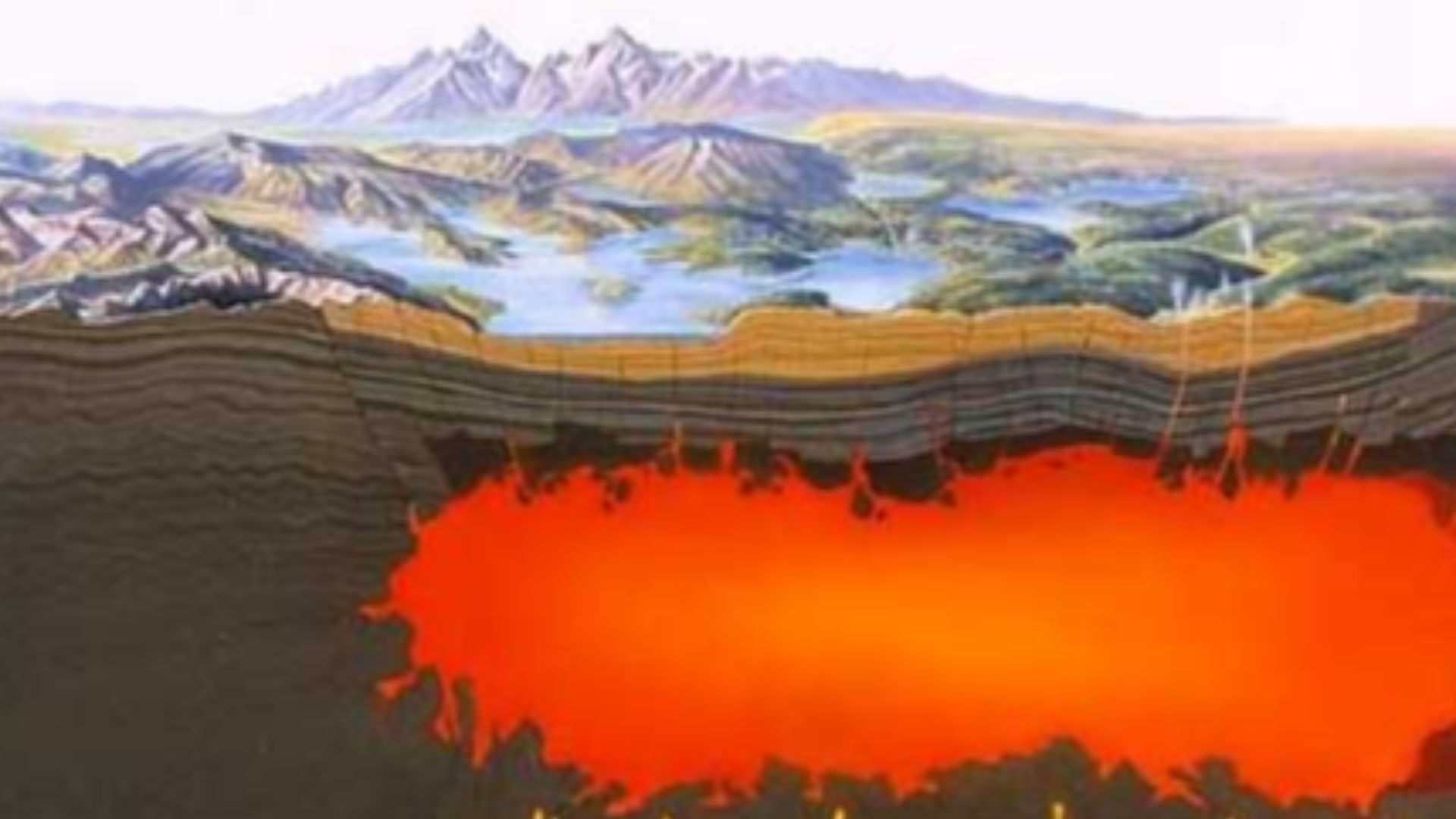

What Makes It Super

The volcano’s classification as a supervolcano comes from the volume of material it can eject. Its system is much larger than the typical cones found worldwide. The enormous magma chambers and widespread geothermal features hint at a far more explosive potential.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Clues From Ancient Ash

Awareness of Yellowstone’s scale grew as researchers mapped ash deposits scattered across North America. These deposits trace back to ancient eruptions far bigger than anything modern humans have seen. The scale of those past blasts helped confirm Yellowstone’s status as one of the planet’s most powerful volcanic systems.

James St. John, Wikimedia Commons

James St. John, Wikimedia Commons

A Giant Underfoot

In the United States, Yellowstone is considered one of the world’s largest active volcanoes, even though it looks peaceful. Its vast underground heat source continuously fuels geysers and hot springs. Every tremor is tracked because any major change could signal shifting conditions deep within the magma reservoirs.

Brocken Inaglory, Wikimedia Commons

Brocken Inaglory, Wikimedia Commons

No Real Way To Prepare

If Yellowstone erupted tomorrow, there would be almost no practical way for anyone in North America to prepare. The speed, scale, and unpredictability of a supervolcano mean that evacuation zones would be enormous. Millions living near the region would face immediate, unavoidable danger once the eruption began.

Dietmar Rabich, Wikimedia Commons

Dietmar Rabich, Wikimedia Commons

Why People Worry

Yellowstone’s eruptions are rare. The last major one occurred about 600,000 years ago, which has people wondering whether another might happen soon. Geological timelines move slowly, so “near future” usually means hundreds of thousands of years. Scientists there emphasize that nothing suggests a supervolcanic blast is imminent.

F. Jay (Frank Jay) Haynes, Wikimedia Commons

F. Jay (Frank Jay) Haynes, Wikimedia Commons

A Different Kind Of Blast

A supervolcano produces much more material than a typical eruption. People imagine rivers of lava pouring across the land, but Yellowstone behaves differently. Its eruptions throw vast amounts of ash into the air. That airborne material becomes the most destructive force during a supervolcanic event.

Yellowstone National Park, Wikimedia Commons

Yellowstone National Park, Wikimedia Commons

Surprisingly Little Lava

Surprisingly, Yellowstone wouldn’t release enormous lava flows. Much of its magma would blast upward as ash before reaching the surface. This prevents large lava fields from forming. But don’t be fooled, the limited lava isn’t comforting because the airborne particles cause far greater destruction across continents.

James St. John, Wikimedia Commons

James St. John, Wikimedia Commons

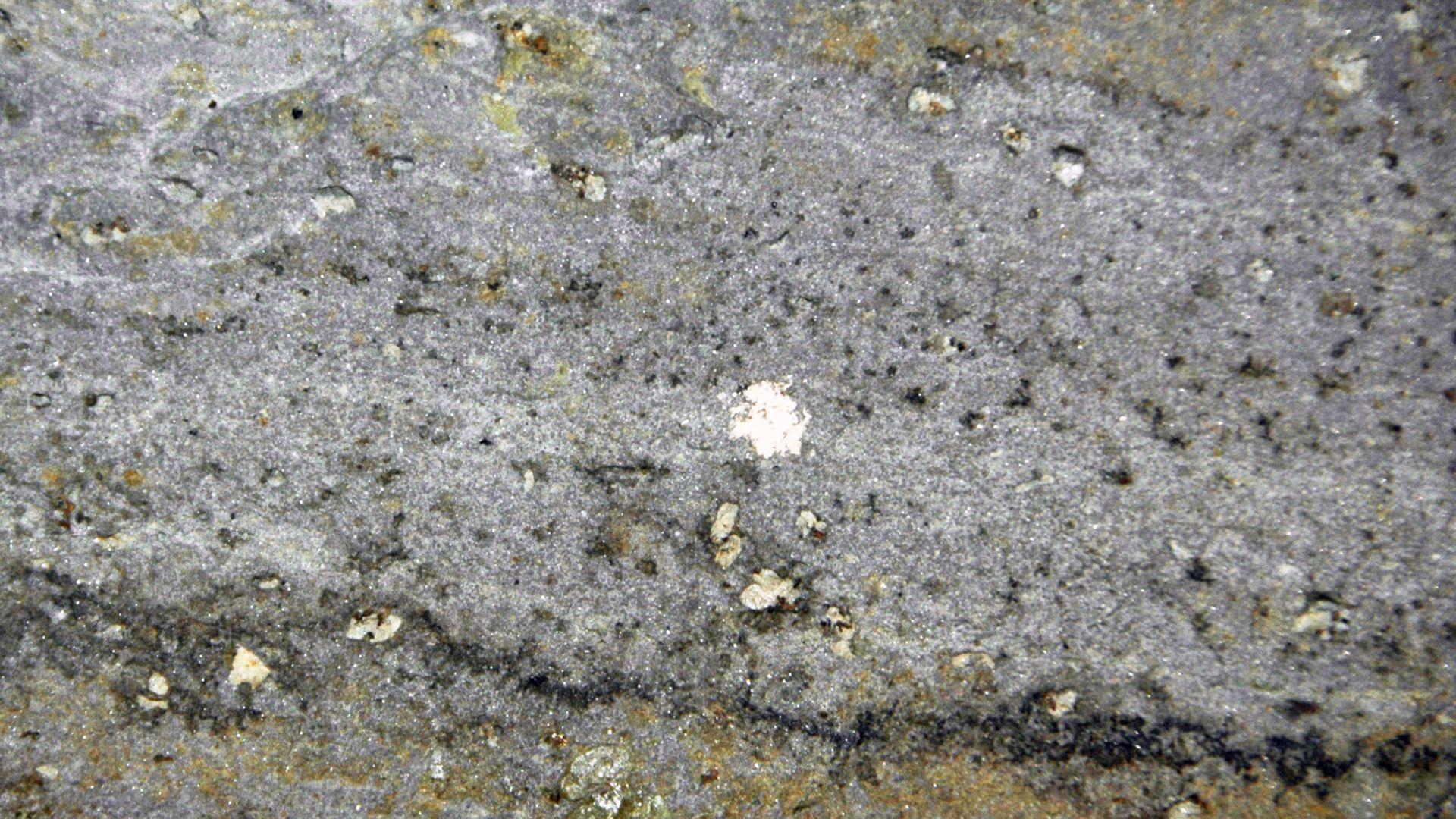

Ash That Cuts

The ash created by a Yellowstone eruption wouldn’t resemble soft fireplace soot. These particles are tiny, sharp fragments of rock heated to extreme temperatures. Once airborne, they travel on high winds and spread far across the continent. This turns entire regions into hazardous, ash-filled environments.

James St. John, Wikimedia Commons

James St. John, Wikimedia Commons

The Deadly Ash Zone

Nearly the entire United States and much of Canada would be affected by ash. Tens of millions living within a thousand kilometers of the blast would face lethal conditions. Ash mixing with moisture in the lungs forms a cement-like substance, quickly suffocating anyone exposed during the event.

Buildings Can’t Handle It

Because the ash is heavy, buildings would collapse under its weight. Just twelve inches on a rooftop can cause widespread structural failure. Communities far outside the immediate blast zone would still face dangerous fallout, overwhelmed hospitals, and failing infrastructure as ash blankets critical systems.

John E. Thwaites, Wikimedia Commons

John E. Thwaites, Wikimedia Commons

The East Still Gets Hit

Even places on the East Coast would receive about one centimeter of ash. That small amount still poses serious health risks. Power grids and water supplies would all experience disruptions as the fine material clogs systems and reduces visibility across wide regions.

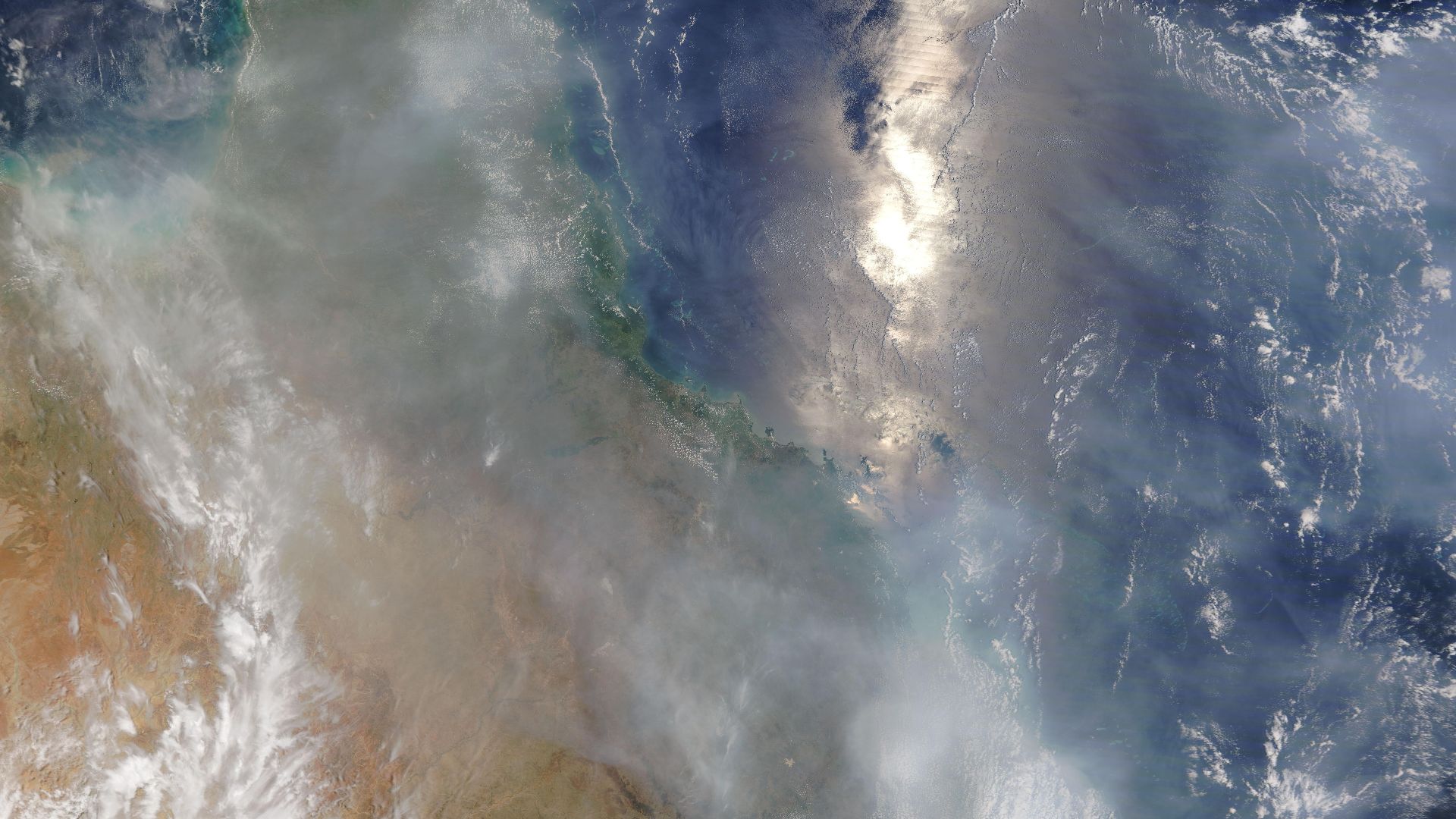

Ash Reaching Europe

Parts of Europe could see a light dusting of ash as the plume travels globally. Although not deadly at that distance, the particles mark the massive scale of the eruption. Winds would carry material around the world, demonstrating how far-reaching a supervolcano’s impact becomes.

MODIS Land Rapid Response Team, NASA GSFC, Wikimedia Commons

MODIS Land Rapid Response Team, NASA GSFC, Wikimedia Commons

A Decade Of Cooling

Beyond immediate fallout, the ash cloud would block sunlight. Without normal levels of solar radiation, global temperatures would drop significantly. It’s estimated that a ten-degree decline will last up to a decade and reshape weather patterns. It may push the planet into a prolonged period of colder conditions.

Matt Riggott from Reykjavík, Iceland, Wikimedia Commons

Matt Riggott from Reykjavík, Iceland, Wikimedia Commons

Crops Collapse Fast

Crops would fail across multiple regions because plants suffocate under ash layers, and reduced sunlight halts growth cycles. For these reasons, agriculture in the western hemisphere would collapse quickly. Food shortages would spread worldwide as disrupted supply chains and long-term cooling reshape farming conditions.

Katmai National Park and Preserve, Wikimedia Commons

Katmai National Park and Preserve, Wikimedia Commons

Water Turns Hazardous

Water systems would suffer immediate contamination. Ash falling into rivers and reservoirs forms sludge-like mixtures that damage filtration systems. Communities relying on surface water would also face dangerous shortages. Cleaning and restoring water infrastructure after such widespread contamination would require massive rebuilding efforts.

Survival Isn’t Guaranteed

The initial blast might spare some people far from Yellowstone, but long-term effects would eventually reach them. Ash contamination, colder weather, and disrupted global supplies create harsh living conditions. Surviving the eruption wouldn’t guarantee stability as daily life becomes increasingly difficult.

U.S. Forest Service- Pacific Northwest Region, Wikimedia Commons

U.S. Forest Service- Pacific Northwest Region, Wikimedia Commons

Cold Changes Everything

The Western world would struggle through a decade of extreme climate change triggered by sunlight reduction. Colder temperatures and disrupted seasons would alter ecosystems. Wildlife populations would decline, and forests would suffer from reduced sunlight and dramatic shifts in water availability.

The Good News

Fortunately, such an eruption is extremely unlikely in our lifetimes. Monitoring systems track ground motion and temperature changes. Nothing observed suggests the volcano is preparing for a supervolcanic event anytime soon. This information offers reassurance to people despite Yellowstone’s dramatic reputation.

Yellowstone National Park, Wikimedia Commons

Yellowstone National Park, Wikimedia Commons

More Likely Eruption Type

Yellowstone is far more likely to produce a hydrothermal eruption. These events involve steam explosions powered by superheated groundwater. While dangerous near the blast area, they affect much smaller zones and lack the continent-wide consequences that define supervolcanic eruptions.

Brocken Inaglory, Wikimedia Commons

Brocken Inaglory, Wikimedia Commons

Steam Blasts Instead

Hydrothermal blasts throw rocks and release powerful jets of steam. Visitors near geysers and hot springs would be at risk, but such events remain localized. These eruptions are considered a natural part of Yellowstone’s geothermal activity rather than indicators of larger volcanic trouble.

Brocken Inaglory: Brocken Inaglory, Wikimedia Commons

Brocken Inaglory: Brocken Inaglory, Wikimedia Commons

Lava Flows Are Common

An even more likely scenario is a simple lava flow. Yellowstone has produced nearly fifty flows over the last 600,000 years. None caused casualties. These slow-moving events are far less destructive, which allows plenty of time for people to move away safely.

James St. John, Wikimedia Commons

James St. John, Wikimedia Commons

Slow Lava, Small Danger

Lava flows reshape land but don’t threaten distant communities. They typically follow predictable paths determined by topography. Although visually dramatic, these eruptions pose minimal danger compared to explosive activity. Scientists see them as manageable events within Yellowstone’s long geological history.

James St. John, Wikimedia Commons

James St. John, Wikimedia Commons