Carved In Terror

Most museum pieces sit quietly behind glass, harmless and historical. Then there are the others. Objects that carried weight in their time and somehow still do. Ancient cultures left evidence of their darkest beliefs.

The Screaming Mummies

The ancient Egyptians mastered the art of mummification, preserving bodies for eternity with meticulous care and ritual precision. Yet among the thousands of mummies discovered in Egypt's vast necropolises, one stands out for all the wrong reasons—a mummy frozen in what appears to be an eternal scream.

The Screaming Mummies (Cont.)

Found in the Deir el-Bahri cache, this famously nicknamed "Screaming Mummy" presents an open-mouth expression that immediately unsettles anyone who gazes upon it, defying the peaceful repose typically associated with Egyptian funerary practices. The contorted facial expression has sparked intense debate among Egyptologists about what could have caused such a dramatic pose.

Keith Hazell, Wikimedia Commons

Keith Hazell, Wikimedia Commons

Tollund Man

When peat cutters were working in a Danish bog in 1950, they stumbled upon what they initially believed to be a fresh murder victim, as the body was simply too well-preserved to be ancient. Tollund Man, as he came to be known, is a remarkably intact Iron Age bog body.

Tollund Man (Cont.)

His skin, facial features, and hair survived intact thanks to the unique chemistry of peat bogs, which inhibit decay through their acidic, oxygen-poor conditions. His serene expression and visible stubble give him an almost lifelike quality that bridges the millennia between his demise and our present day.

Nils Jepsen /user:Nico, Wikimedia Commons

Nils Jepsen /user:Nico, Wikimedia Commons

Aztec Death Whistles

Imagine standing on a pre-Columbian battlefield and hearing a sound like a thousand souls screaming in unison. This noise was so unsettling that it could freeze warriors in their tracks or signal the arrival of something beyond the mortal realm.

Papeleria alfa23, Wikimedia Commons

Papeleria alfa23, Wikimedia Commons

Aztec Death Whistles (Cont.)

Clay "death whistles" recovered from Mesoamerican archaeological contexts were designed to produce exactly this effect. Associated with ritual use, these small instruments could generate terror through sound alone, weaponizing acoustics in ways that modern warfare would not achieve until centuries later.

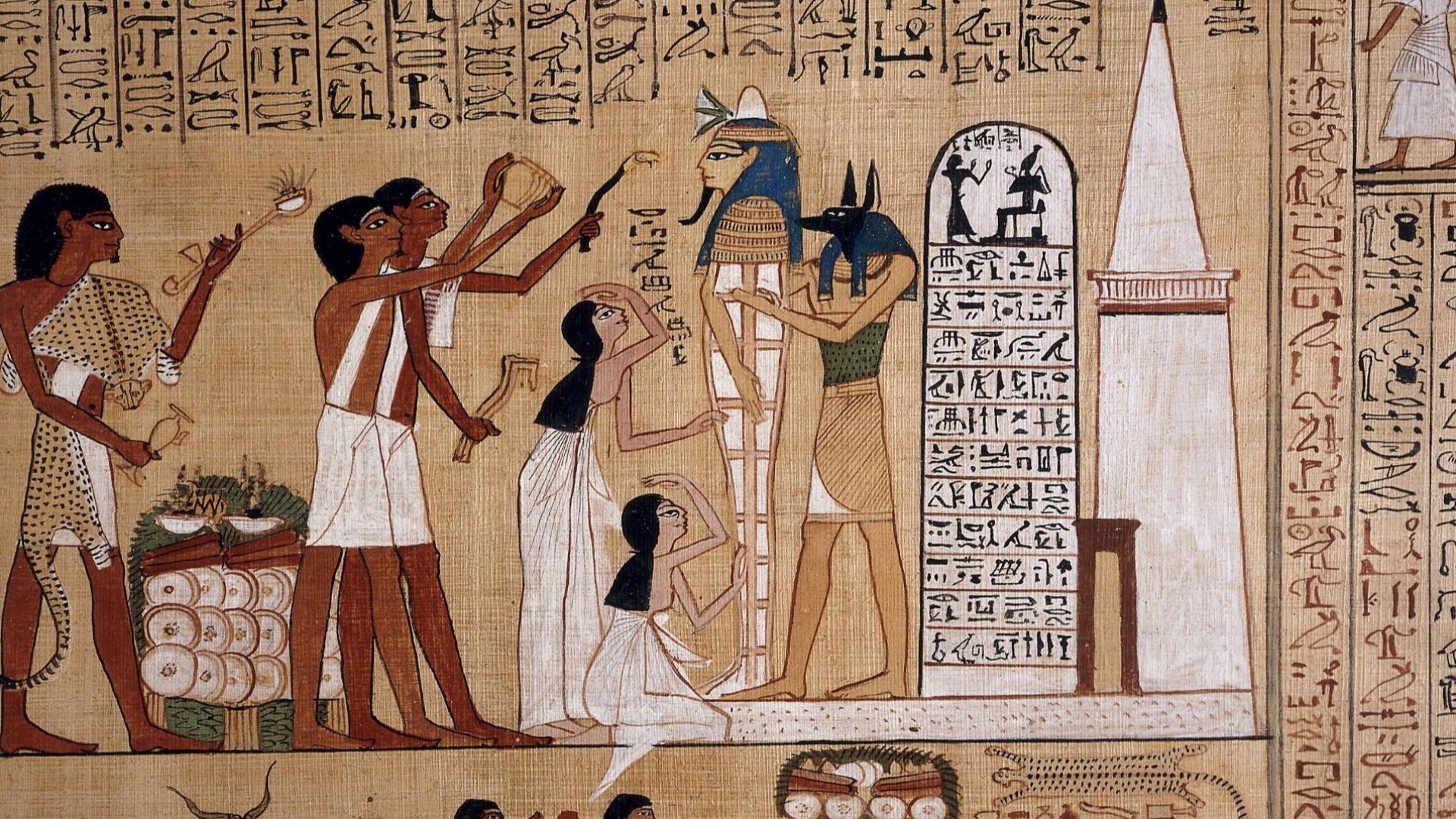

Egyptian Canopic Jars

The ancient Egyptian approach to death was nothing if not thorough, and nowhere is this more evident than in their treatment of internal organs during mummification. Canopic jars were essential vessels used to store and protect organs removed during embalming, each carefully extracted, preserved, and placed in its designated container.

Yair-haklai, Wikimedia Commons

Yair-haklai, Wikimedia Commons

Egyptian Canopic Jars (Cont.)

The four jars held profound religious significance, each associated with one of the four sons of Horus, who served as divine protectors for specific organs. Imsety guarded the liver, Hapy the lungs, Duamutef the stomach, and Qebehsenuef the intestines—their distinctive heads often carved as lids on the jars themselves.

Lizard Figurines Of Ubaid

Long before the great cities of Mesopotamia rose along the Tigris and Euphrates, small communities of the Ubaid period were already crafting mysterious terracotta figurines that continue to puzzle archaeologists today. Dating from the 6th to 4th millennium BCE, southern Mesopotamia's Ubaid-period sites have produced numerous small animal figurines.

Mary Harrsch, Wikimedia Commons

Mary Harrsch, Wikimedia Commons

The Chavin Raimondi Stela

Deep in the Andean highlands of Peru, the ancient Chavin culture created one of the most sophisticated pieces of visual trickery in the pre-Columbian world. The Raimondi Stela is a carved stone monument from Chavin de Huantar that demonstrates an artistic mastery far beyond what many assume about ancient American civilizations.

Markus Kollner, Wikimedia Commons

Markus Kollner, Wikimedia Commons

The Chavin Raimondi Stela (Cont.)

What makes this stela truly extraordinary is its intricate, interlocking design that depicts a staff-bearing deity. But here's where it gets genuinely unsettling: when you flip the image upside down, an entirely different figure emerges, changing before your eyes through deliberate artistic manipulation.

Ariadnayteseo, Wikimedia Commons

Ariadnayteseo, Wikimedia Commons

Labyrinth Of Knossos

The palace complex at Knossos on Crete was a sprawling maze that would inspire one of Greek mythology's most terrifying legends. Excavations by Sir Arthur Evans in the early 20th century revealed elaborate frescoes, storage rooms, and a layout so confusing that visitors today still struggle to navigate its reconstructed corridors.

ArchaiOptix, Wikimedia Commons

ArchaiOptix, Wikimedia Commons

Labyrinth Of Knossos (Cont.)

With its multi-room plan featuring dead ends, winding passages, and interconnected chambers, it's easy to see how this architectural complexity inspired the Greek myth of the Labyrinth, where the monstrous Minotaur supposedly dwelt. Archaeologists link the site to Minoan ceremonial, administrative, and possibly ritual activities.

ArchaiOptix, Wikimedia Commons

ArchaiOptix, Wikimedia Commons

Cueva De Las Lechuzas

"Cueva de las Lechuzas" translates to "Cave of the Owls," a name given to several caves throughout Spanish-speaking regions, each known for its resident wildlife. The name itself reflects the long human habit of linking natural places to the creatures that inhabit them and the stories that grow around them.

Cueva De Las Lechuzas (Cont.)

These caves often preserve organic remains and artifacts with remarkable fidelity because stable cave microclimates provide ideal conditions for preservation. Archaeologists frequently investigate caves bearing this name for evidence of past human use, burials, or ritual activity, and they rarely come away disappointed.

The Gobekli Tepe Pillars

Everything archaeologists thought they knew about the development of human civilization was challenged when Gobekli Tepe was discovered in southeastern Turkey. This site features massive T-shaped stone pillars carved with animal reliefs. Boars, foxes, lions, scorpions, and vultures are rendered with startling artistry.

The Gobekli Tepe Pillars (Cont.)

Previously, the assumption was simple: first came farming, then surplus food, then specialized labor, and finally monumental architecture and complex religion. Gobekli Tepe flips this narrative entirely, suggesting that organized religion and the need for communal gathering spaces may have actually motivated the transition to agriculture rather than resulting from it.

Trundholm Sun Chariot

Found in a peat bog, the Trundholm Sun Chariot is one of the Bronze Age's most visually stunning artifacts—a horse-drawn chariot carrying a gilded sun disk that still gleams under museum lights after three thousand years. This Bronze Age Danish artifact represents far more than mere craftsmanship.

National Museum of Denmark, Wikimedia Commons

National Museum of Denmark, Wikimedia Commons

Trundholm Sun Chariot (Cont.)

It's a cosmological object reflecting Bronze Age sun worship or myth, offering insight into how Nordic peoples understood the daily journey of the sun across the sky. The chariot's wheels still turn, and one can almost imagine it being pulled in ceremonial processions or buried as an offering.

Marie-Lan Nguyen, Wikimedia Commons

Marie-Lan Nguyen, Wikimedia Commons

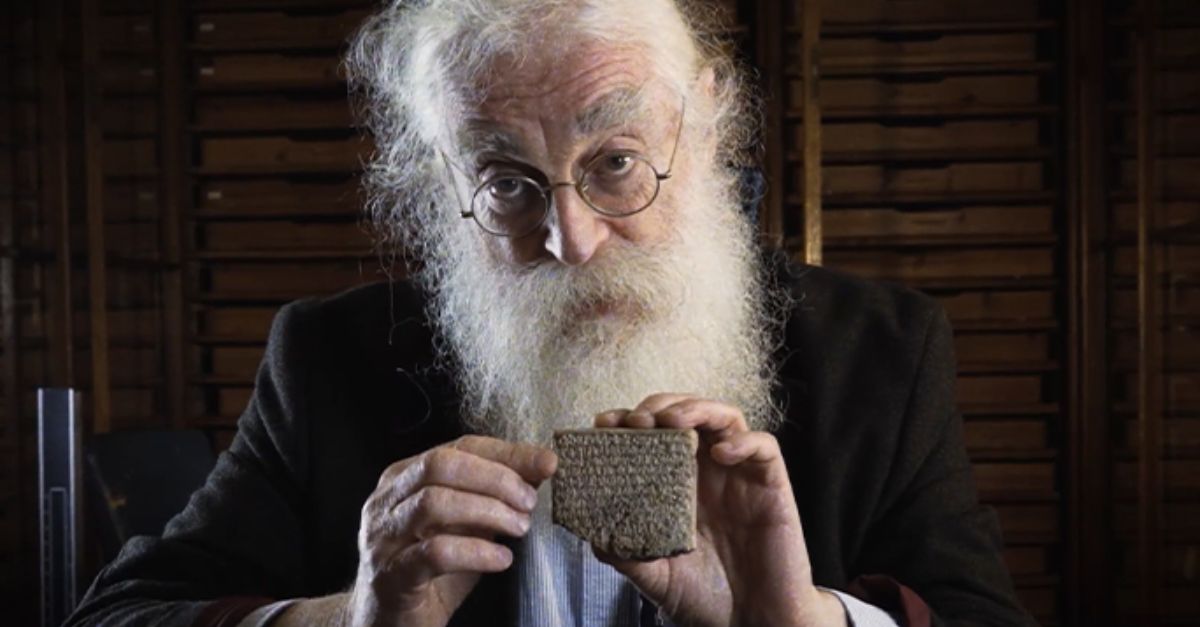

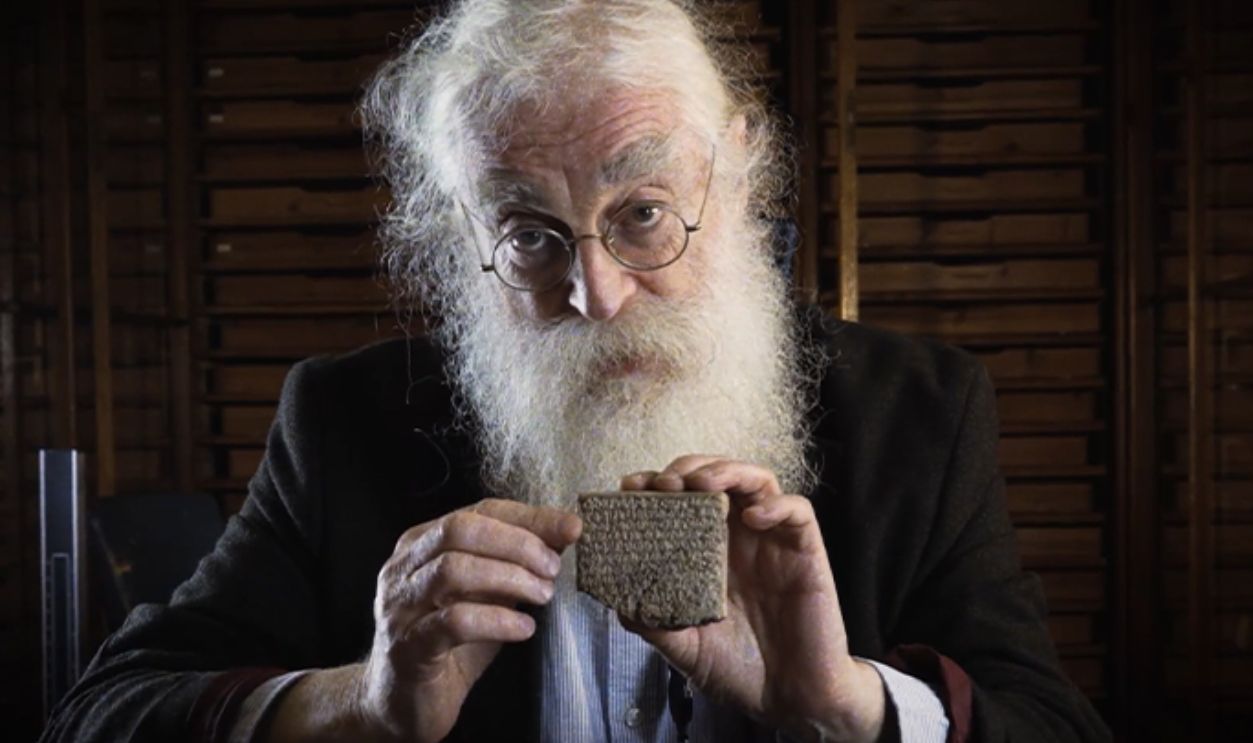

Exorcism Tablets

When ancient Mesopotamians faced illness, misfortune, or disturbing dreams, they called upon ritual specialists armed with clay tablets containing the knowledge to combat invisible forces. Mesopotamian cultures recorded exorcistic rituals and incantations on clay tablets used by these experts, creating what were essentially instruction manuals for supernatural warfare.

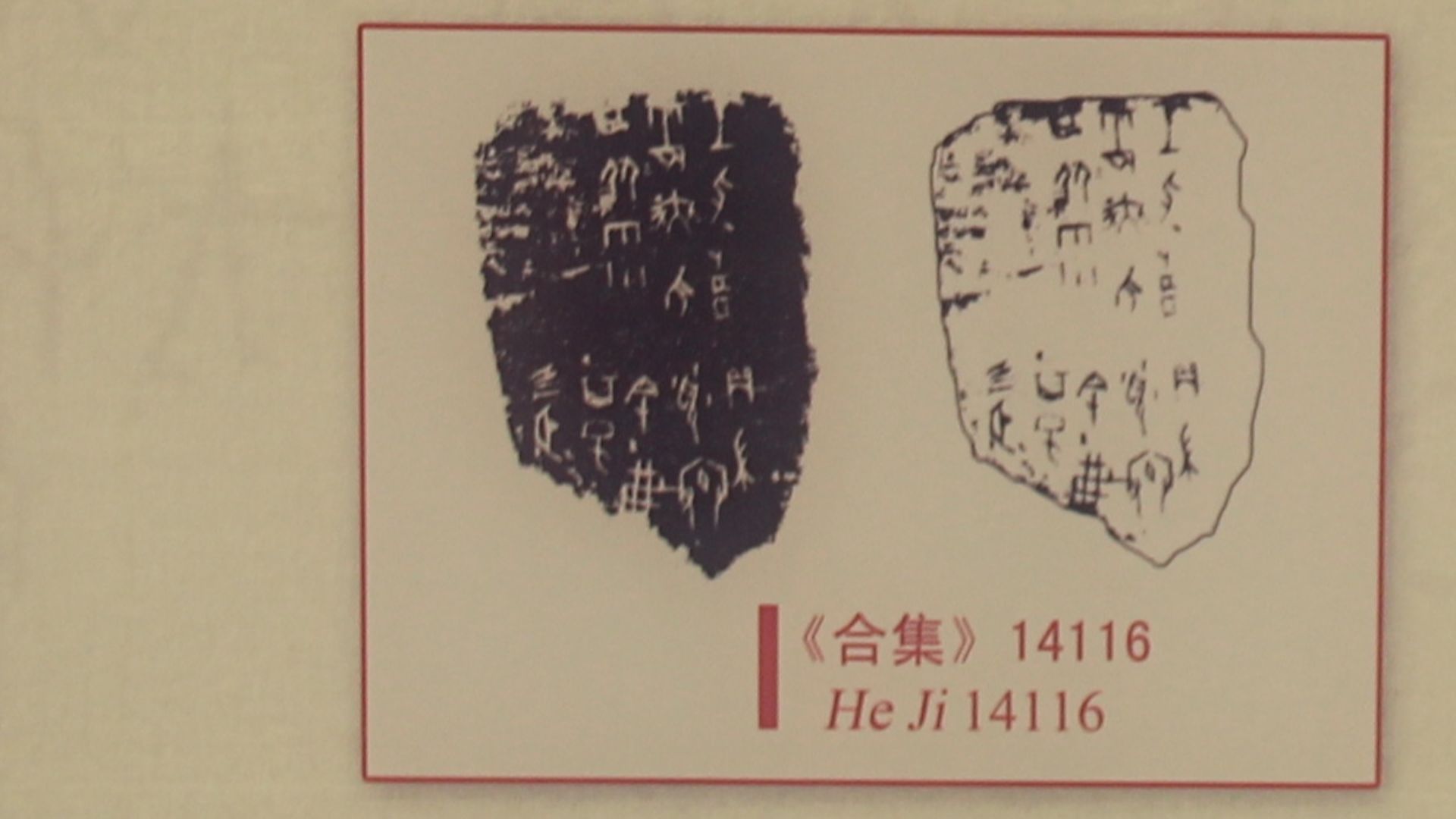

The Oracle Bones

Oracle bones are ox scapulae and turtle plastrons that Shang-period China turned into a direct communication line with ancestors and gods, bearing the earliest Chinese inscriptions we possess. These weren't casual queries but matters of state importance. When to plant crops, whether to wage war, if the king's toothache signified divine displeasure, and whether the upcoming harvest would succeed.

photograph by Gary Todd, cropped by Kanguole, Wikimedia Commons

photograph by Gary Todd, cropped by Kanguole, Wikimedia Commons

Demon Bowls

Late Antique Mesopotamia and the eastern Mediterranean developed a peculiar form of home security: ceramic bowls inscribed with incantations and buried upside down beneath house floors to trap malevolent spirits. These "demon" or incantation bowls were the ancient world's answer to supernatural home invasion.

The Hand Of Sabazius

Bronze votive hands associated with the cult of Sabazius were offered in Roman and provincial sanctuaries as religious dedications, creating one of the most visually distinctive artifact types from the Roman world. The hands often bear symbols such as snakes coiling around fingers, pine cones, lizards, and frogs.

Anonymous (Category:Roman Empire)Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Anonymous (Category:Roman Empire)Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

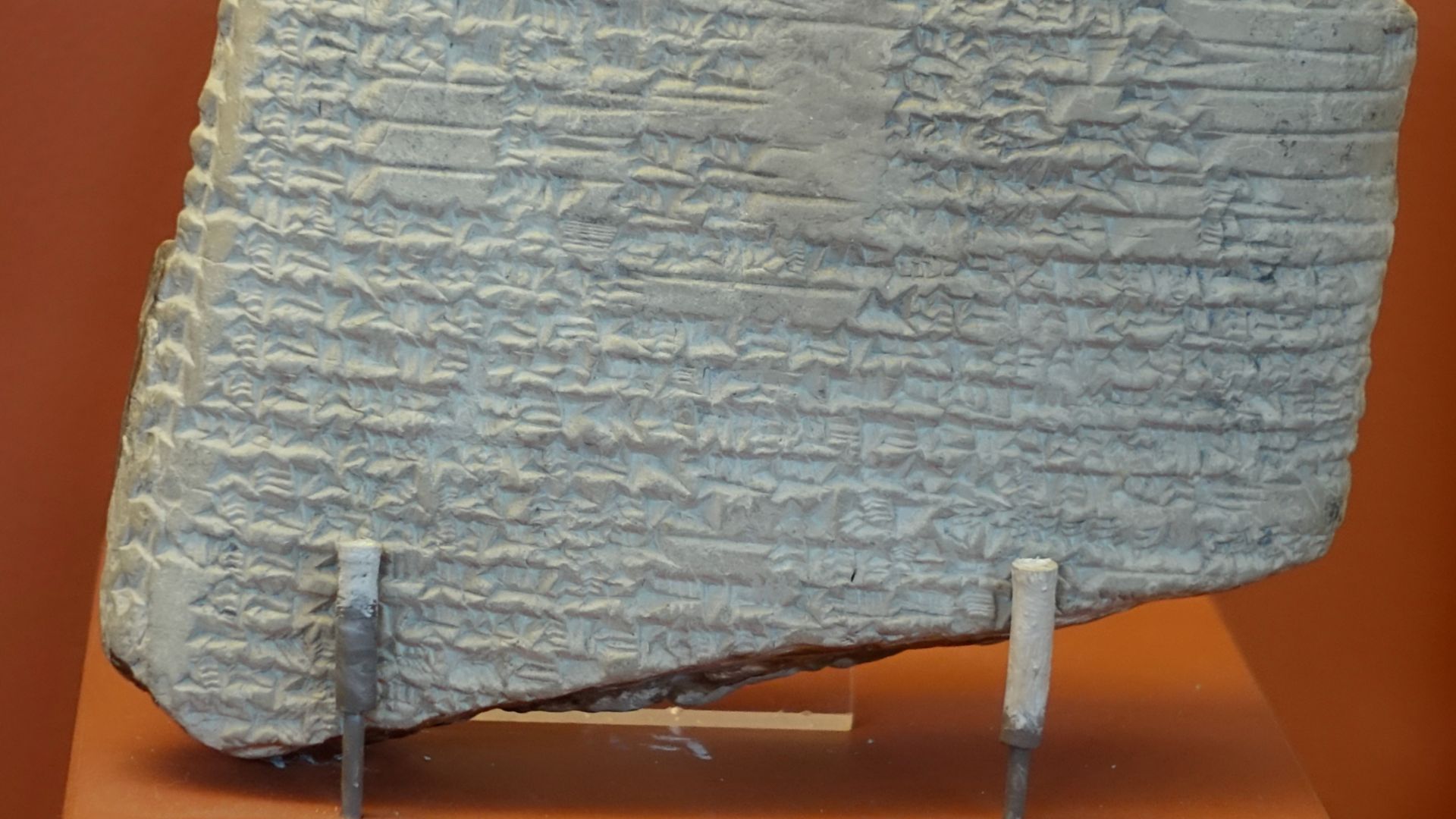

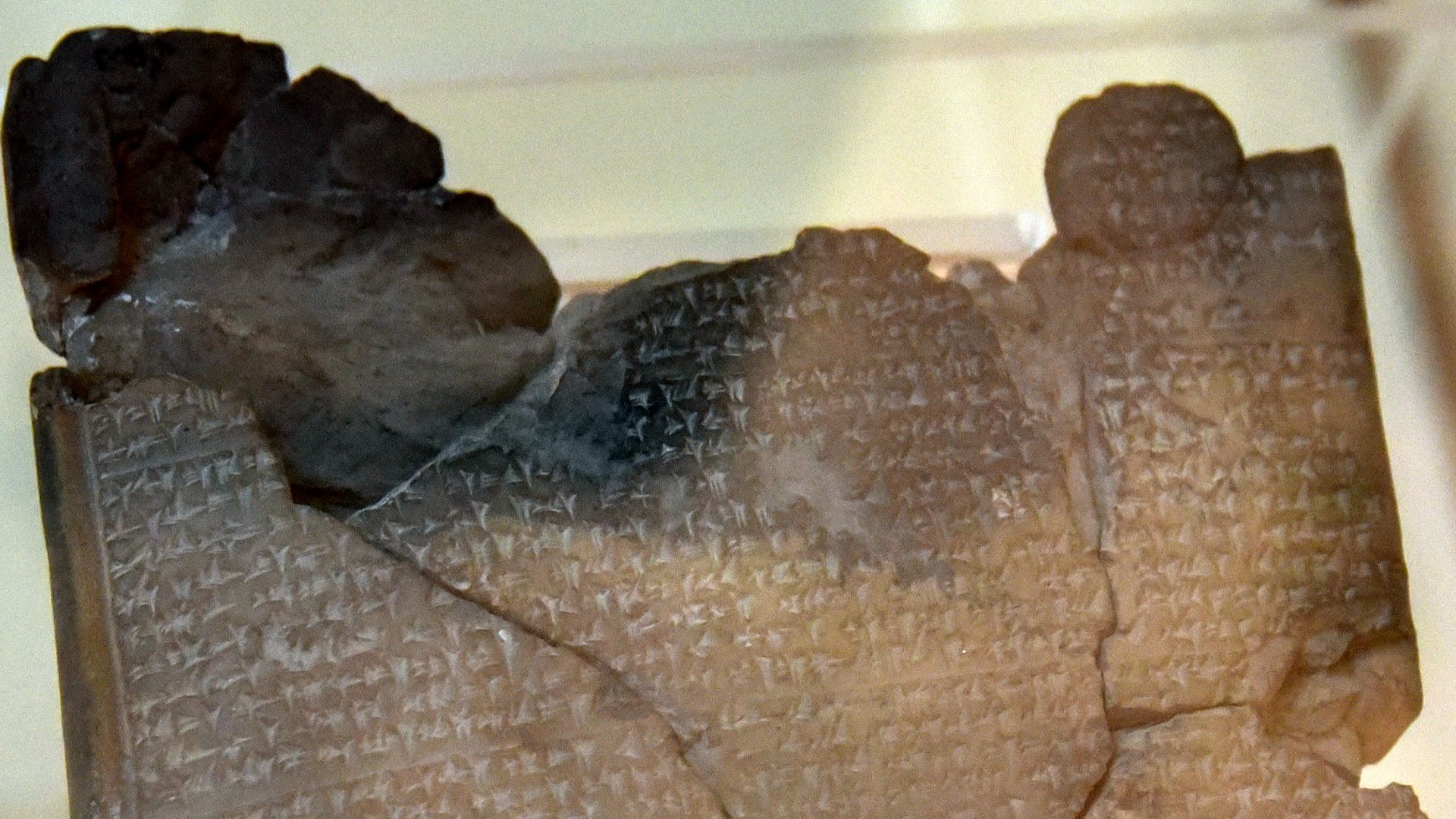

Hittite Plague Prayers

When epidemic disease swept through the Hittite Empire in the 14th century BCE, killing thousands and threatening the kingdom's stability, the royal archives preserved desperate prayers. Hittite cuneiform archives include ritual texts and prayers invoked during plagues and epidemics. These texts prescribe purification rites and appeals to the gods to remove disease.

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons