A Church Built On Graves

During routine repair work, construction crews uncovered a hidden staircase beneath a historic building. What lay below was not part of any modern plan, but a sequence of buried spaces revealing centuries of continuous use.

GO69, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons, Modified

GO69, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons, Modified

The Church That Hid Centuries Underground

Saint Philibert Church in Dijon, France, stands as the city's only Romanesque structure built "in the manner of the Romans" during the 12th century. Located near the towering Saint-Benigne Cathedral on rue Michelet, this architectural gem has witnessed eight centuries of transformation and turmoil.

A 1970s Renovation Gone Terribly Wrong

Someone installed a heated concrete slab in the early 1970s, thinking it would modernize the medieval church. The decision proved disastrous because the building had stored salt during the 18th and 19th centuries. Heat drew moisture and salt upward into the stone pillars, which caused them to crack and burst apart.

Why Salt Became The Church's Enemy

After being decommissioned following the French Revolution, Saint Philibert was repurposed to store salt. That salt embedded itself deep into the soil and mortar through capillary action. The chlorides saturated the ground, slowly ascending through the porous stone structures over decades.

Routine Repairs That Turned Into An Excavation

Restoration crews from the National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research (INRAP) arrived to assess foundation damage caused by salt. Workers lifted a section of stone flooring to inspect structural integrity. What they found underneath wasn't on any renovation plan—a staircase that shouldn't have existed.

Elyane Ferrari, Wikimedia Commons

Elyane Ferrari, Wikimedia Commons

The Archaeologists Who Led The Dig

Dr. Clarisse Couderc and Carole Fossurier from INRAP took charge of the unexpected excavation project. Couderc specializes in how medieval cities reused sacred buildings as political and worship needs reshaped neighborhoods. Her expertise proved crucial for interpreting the layered discoveries that followed.

Bureau of Land Management, Wikimedia Commons

Bureau of Land Management, Wikimedia Commons

A Staircase Sealed Since The 1970s

The forgotten staircase had been blocked off and hidden since the early 1970s, approximately 50 years before restoration workers rediscovered it. No documentation existed showing its location or purpose in any church records. Archaeologists carefully descended the steps, unsure what awaited them at the bottom.

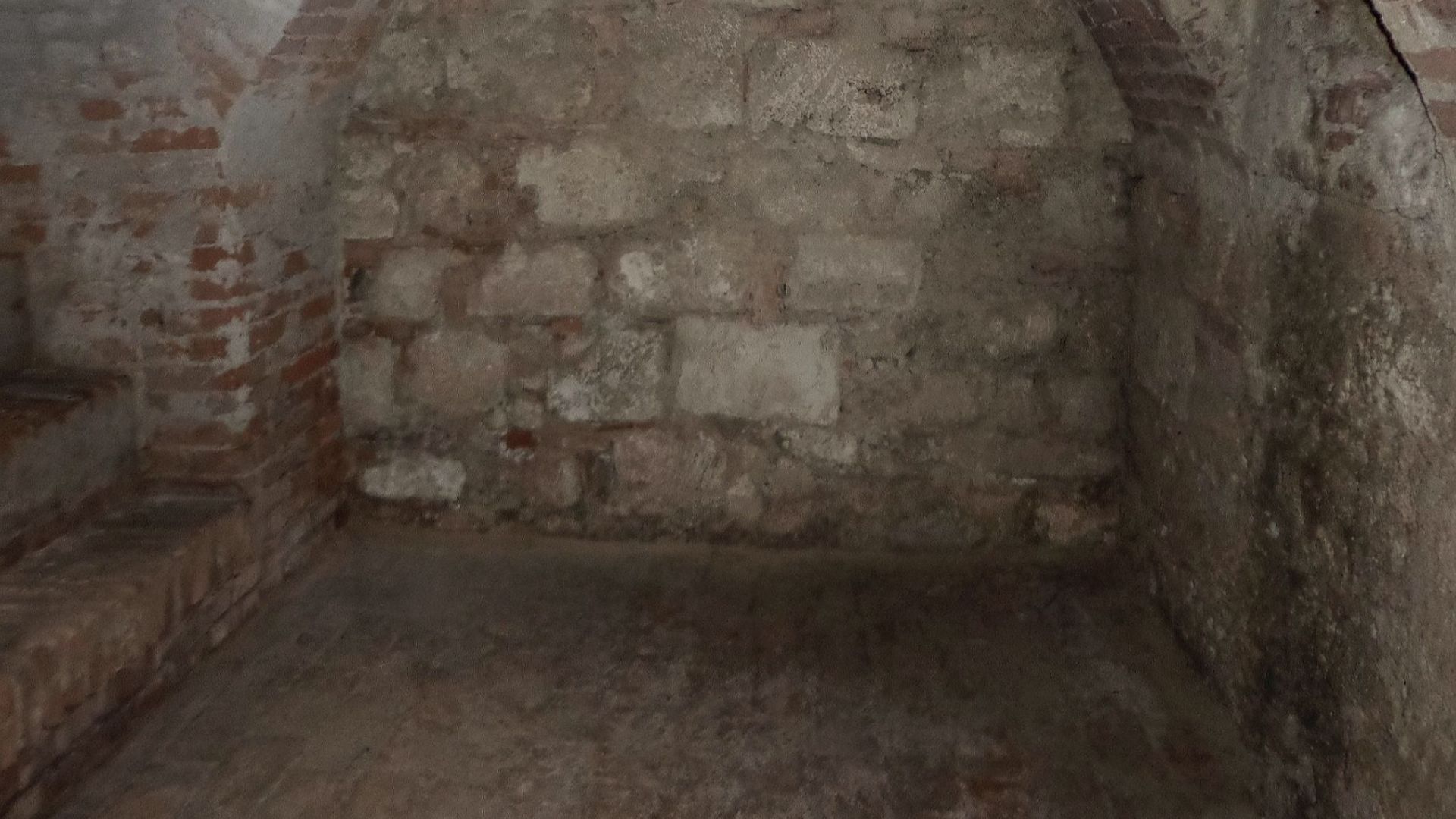

The 400-Year-Old Burial Vault

At the staircase's base sat a vaulted chamber from the 15th–16th centuries, sealed and untouched for 400 years. Inside the transept vault, wooden coffins contained remains of children and adults from late medieval times. The foundation measured roughly 9 feet deep.

Bodies Pushed Aside For New Arrivals

Earlier burials had their bones moved to the vault's sides to accommodate fresh corpses. This practice of reusing burial space was common when cemetery room ran scarce. Each new death meant rearranging the previous occupants, creating jumbled skeletal remains throughout the chamber.

Florian Loschek, Wikimedia Commons

Florian Loschek, Wikimedia Commons

The Few Objects Found With The Dead

Adults wrapped in shrouds filled most coffins, accompanied by almost no grave goods whatsoever. Archaeologists recovered only rare coins and two rosaries placed near bodies. This minimal burial practice suggests either humble social standing or changing religious customs regarding afterlife possessions.

Wooden Coffins From Four Centuries

In the nave, excavators uncovered rows of wooden coffins dating from the 14th through 18th centuries. All coffins aligned perfectly east-to-west, following traditional Christian burial orientation toward Jerusalem. The wood had survived thanks to stable underground conditions and the dry climate created by salt absorption.

Bernard Gagnon, Wikimedia Commons

Bernard Gagnon, Wikimedia Commons

Slab Tombs Before The Church Existed

Beneath the 400-year-old vault lay stone slab graves from the 11th–13th centuries. These tombs predated the current Romanesque church by decades or even a century. The discovery proved people were burying their dead here long before construction began in the 1100s.

J.Hannan-Briggs , Wikimedia Commons

J.Hannan-Briggs , Wikimedia Commons

Evidence Of A 10th-Century Church

Deeper excavation revealed wall remnants built using opus spicatum—herringbone masonry where stones zigzag like fishbones. This distinctive technique dates to the 10th century and the Early Middle Ages. Archaeologists had found proof of an earlier church structure beneath the Romanesque building.

Theresa Knott, Wikimedia Commons

Theresa Knott, Wikimedia Commons

The 11th Century Church From 1923

An apse discovered during the 1923 excavations suddenly made more sense within this newly exposed archaeological sequence. That earlier dig had hinted at a pre-Romanesque church but lacked context. The 2024 findings confirmed that an 11th-century church once occupied this exact spot.

Michael Garlick , Wikimedia Commons

Michael Garlick , Wikimedia Commons

Six Ancient Sarcophagi Emerge

Stone coffins from Late Antiquity and the Merovingian period came to light beneath the medieval layers. Six sarcophagi in total were unearthed, with four dating to Late Antiquity (5th–6th centuries) and two from the Merovingian era (6th–8th centuries). These were the dig's oldest discoveries, pushing the site's history back 1,500 years.

Merovingian Nobility In Stone Coffins

The two sarcophagi that belonged to the Merovingian dynasty included one associated with the earliest Frankish rulers who governed between the 6th and 8th centuries. This era marked France's transformation from a Roman province to a medieval kingdom. These stone coffins likely held local nobles or church officials who shaped early Christian Burgundy.

Bill Nicholls , Wikimedia Commons

Bill Nicholls , Wikimedia Commons

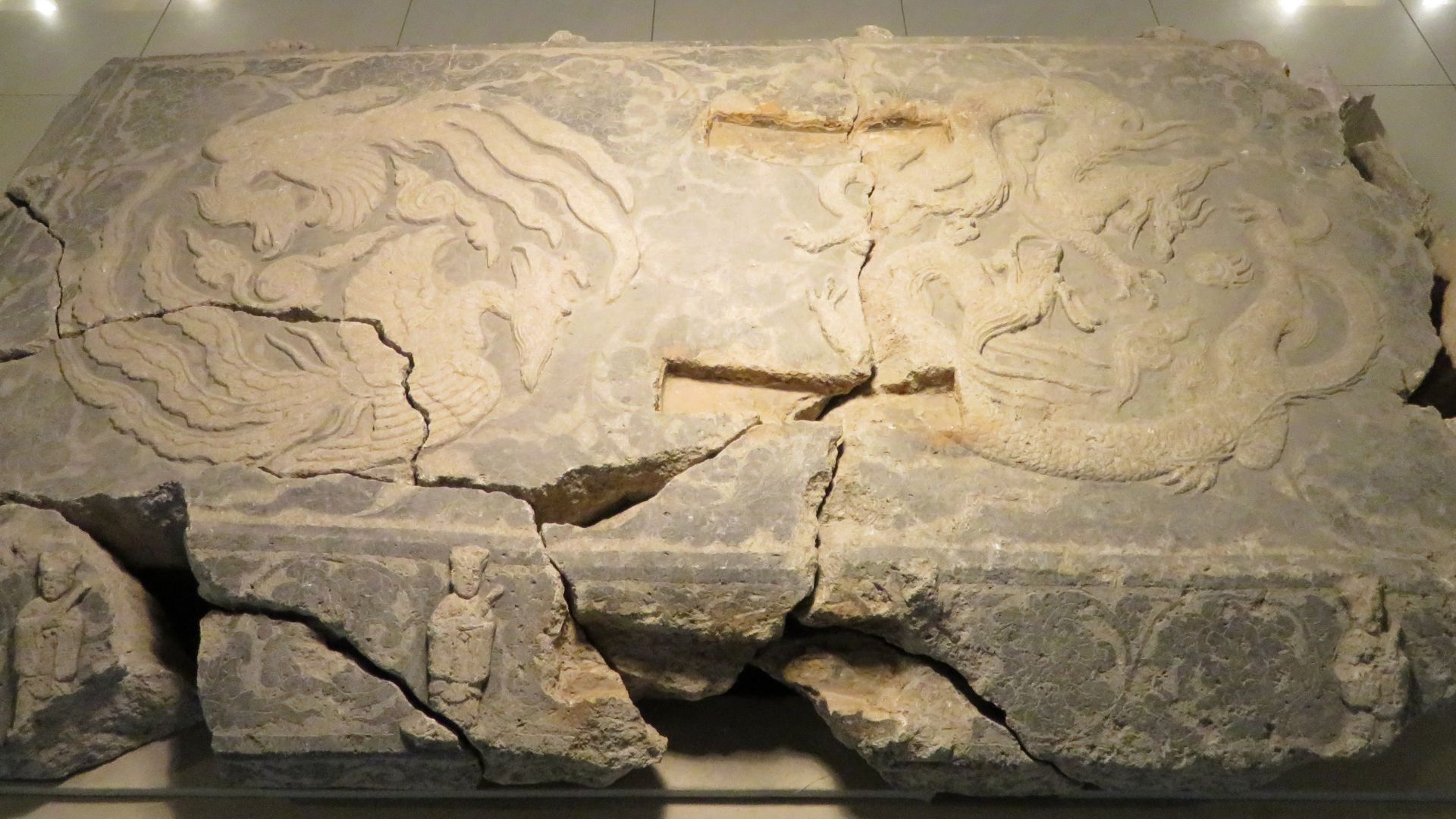

The Sarcophagus With A Sculpted Lid

One sarcophagus stood out with its ornately carved lid. Such decorative elements were rare and expensive, reserved for elite members of late Roman or early Frankish society. The craftsmanship revealed sophisticated stone-carving skills that existed during this transitional period from Roman rule.

Buildings From Late Antiquity Beneath Everything

The sarcophagi rested within the foundations of now-vanished structures with walls running north-south. These buildings functioned during the transition from the Roman Empire to the Early Middle Ages. Archaeologists believe they served religious or funerary purposes, though complete architectural details remain elusive.

David McMumm , Wikimedia Commons

David McMumm , Wikimedia Commons

Why Churches Were Built Atop Churches

Reusing sacred ground was standard practice throughout Christian Europe for practical and symbolic reasons. Ownership was already established, graves created consecrated soil, and existing foundations saved construction effort. Each generation built anew while respecting—or literally building upon—what their ancestors created.

Benjamin Smith, Wikimedia Commons

Benjamin Smith, Wikimedia Commons

A Vertical Timeline Through 1,500 Years

The excavation created a rare stratigraphic record spanning Late Antiquity to modern times without interruption. Most archaeological sites see later construction destroy earlier layers completely. Here, each era sealed and preserved the previous one, creating an intact historical column through the floor.

Johan Allard, Wikimedia Commons

Johan Allard, Wikimedia Commons

The Challenge Of Preserving Salt-Damaged Stone

Conservation efforts now face the ongoing threat of crystallizing salts that form whenever moisture returns. Restorers must carefully manage humidity levels while stabilizing cracked pillars and burst stones. The very salt that helped preserve organic materials underground now threatens the building's structural survival.

Dietmar Rabich, Wikimedia Commons

Dietmar Rabich, Wikimedia Commons

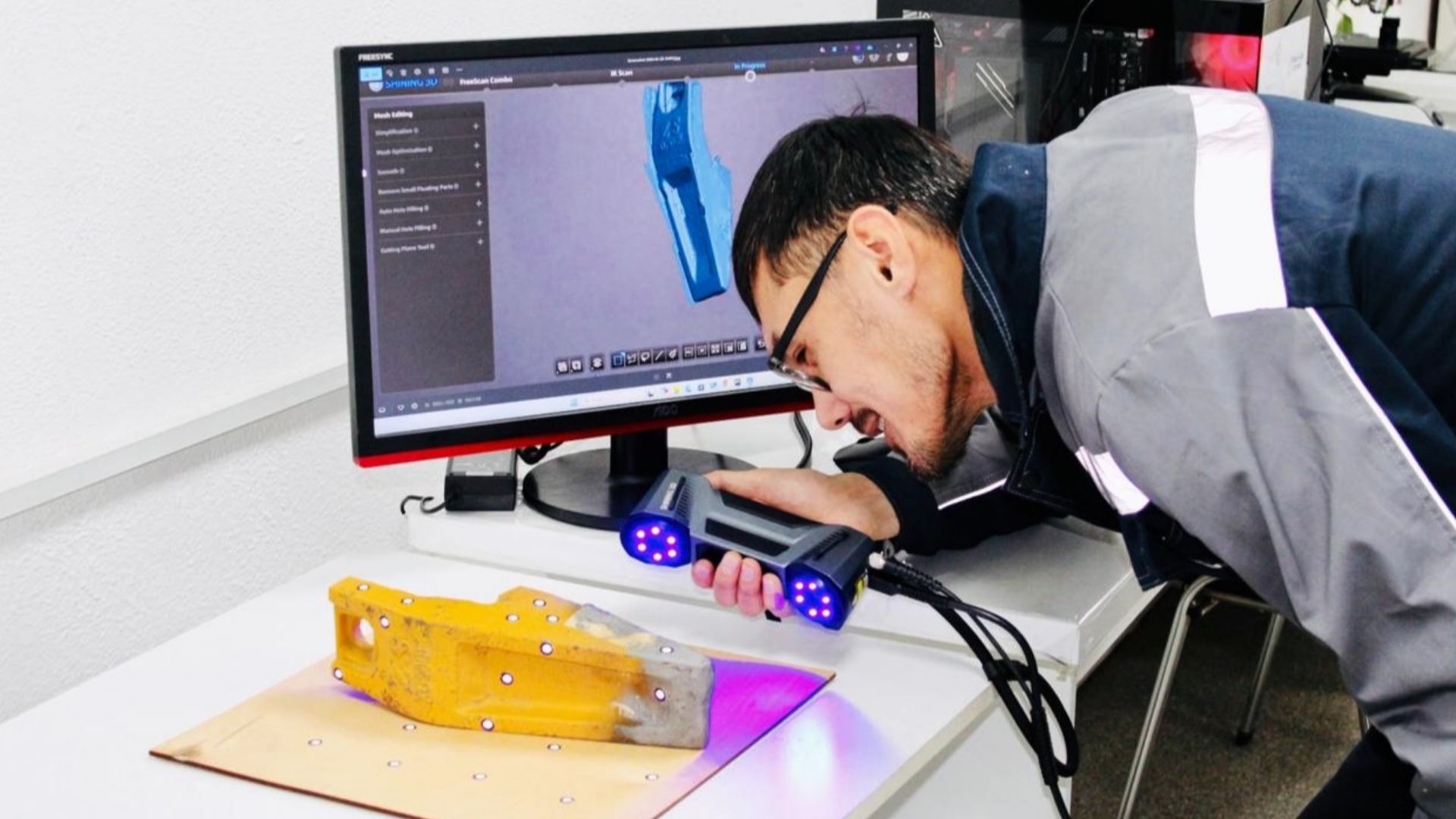

Three-Dimensional Documentation For Posterity

Archaeologists created detailed drawings, photographs, and 3D scans of every layer before removing artifacts. Some bones and stones require reburial, making digital preservation essential for future research. These scans allow scholars worldwide to study the findings without disturbing the actual site.

Surface engineering, Wikimedia Commons

Surface engineering, Wikimedia Commons

What Bone Chemistry Reveals About The Past

Laboratory analysis of skeletal remains can determine diet, migration patterns, and health conditions of the buried individuals. Radiocarbon dating refines timelines for burials that lack clear historical documentation. Bone chemistry essentially reads life stories written in calcium and trace elements.

Yakuzakorat, Wikimedia Commons

Yakuzakorat, Wikimedia Commons

The Site's Significance As An Elite Burial Ground

The presence of decorated sarcophagi and multiple building phases proves this location held special importance for over a millennium. Elite families and church officials chose this spot generation after generation. The site functioned as a continuous funerary center from at least the 5th century onward.

Ongoing Excavation Still Uncovering Secrets

Only a portion of the church floor has been excavated so far, with more layers potentially waiting beneath. Plans call for extending excavation to a depth of 10 feet in select areas. Each shovelful might reveal new surprises about Dijon's transformation from Roman outpost to medieval city.

Crossrail/MOLA, Wikimedia Commons

Crossrail/MOLA, Wikimedia Commons