Bembo De Niro, Shutterstock, Modified

Bembo De Niro, Shutterstock, Modified

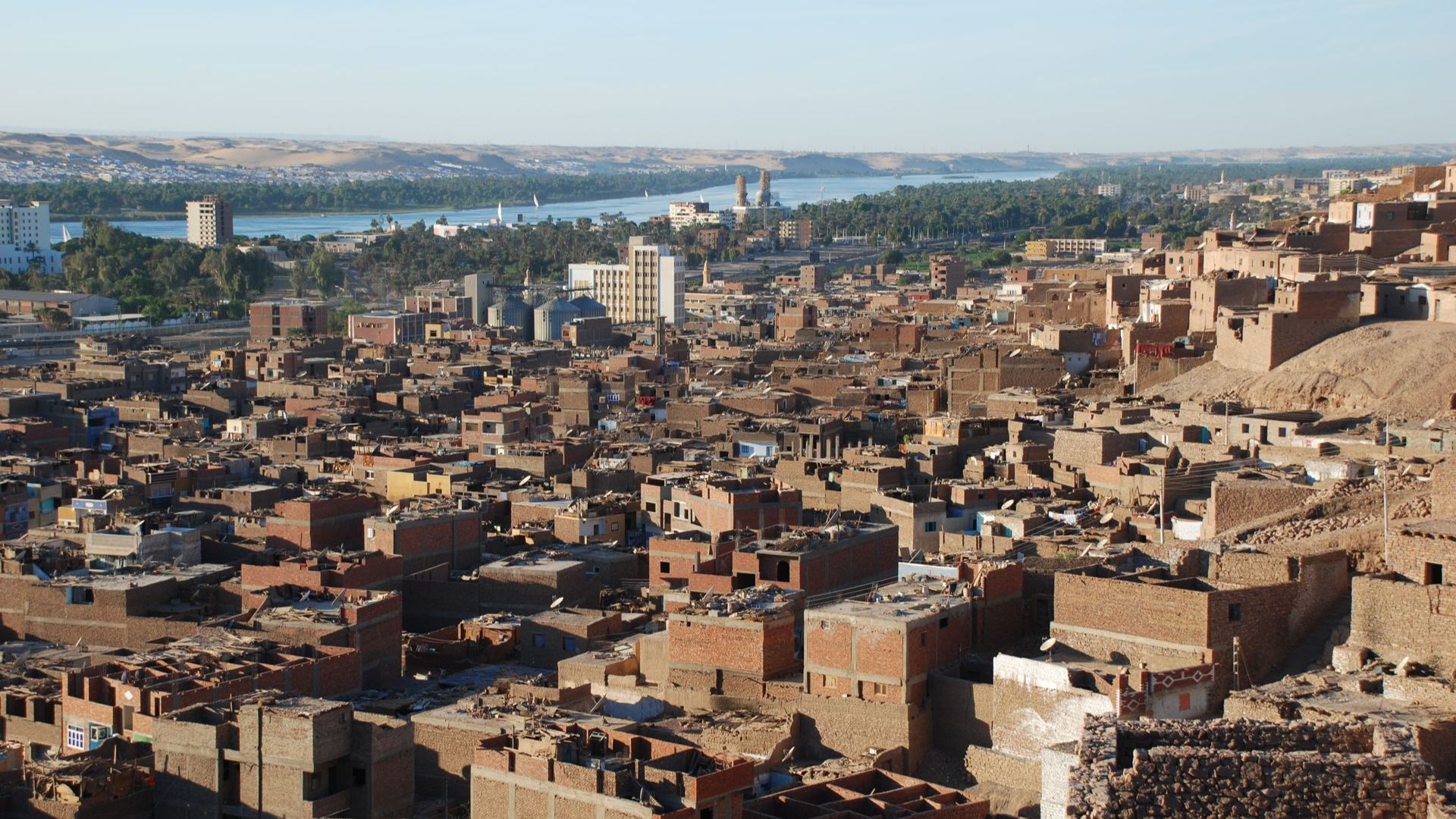

In the golden heat of Aswan’s cliffs, a small cloud of dust rose as archaeologists pried open a sealed rock-cut doorway. For 4,000 years, no one had breathed that air. Inside the tombs of Qubbat al-Hawa, the team found what every Egyptologist dreams of—funerary treasures and painted hieroglyphs lying exactly where ancient hands had left them.

No thieves. No decay. Just time, waiting to be read.

These Tombs Bridge Life And Eternity

According to the Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities analysis, the discovery belongs to Egypt’s Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2181 BCE), with evidence of reuse in the Middle Kingdom.

This was when provincial nobles ruled the frontier from Aswan to Nubia. Each tomb—hewn straight from sandstone—served as both a memorial and spiritual launchpad for local governors.

Architectural features, including false doors, suggest the tombs belonged to local officials who managed trade and diplomacy along the frontier. The sandstone structures, carved into the cliffs, have endured despite centuries of desert wind, to preserve elements like false doors.

The real astonishment came when the team brushed away the final layer of dust.

Looters Never Found These Chambers

Most tombs across Egypt were emptied long before modern archaeology arrived. But here, everything remained intact—Pottery, wooden coffins, and offering tables preserved for millennia.

The best part is that each artifact told a story. The pottery vessels were likely used for afterlife offerings, alongside skeletal remains that provide insights into ancient burial practices.

For researchers, it was as though the past had been carefully preserved, awaiting modern analysis. And carved into those same walls was proof that these weren’t just graves—they were biographies.

The Inscriptions Reveal Power And Prayer

The site's broader records, from nearby tombs, include dedications to deities like Osiris and lists of noble families tied to the Theban court, with phrases praying for “a good burial in the West,” echoing beliefs that life and death were two halves of one journey.

According to ongoing excavations at the site, including by the University of Jaen since 2008, such records from the necropolis map how Aswan’s governors linked Egypt’s heartland to its southern trade routes. Each line, chiseled by candlelight, merges politics with faith—proof that even provincial leaders saw their tombs as eternal resumes.

Vyacheslav Argenberg, Wikimedia Commons

Vyacheslav Argenberg, Wikimedia Commons

A Window Into Daily Life Frozen In Stone

Although decorated Qubbet el Hawa tombs sometimes foreground power and lineage, the chambers in this discovery offer a quieter glimpse shaped by absence rather than display. Archaeologists recorded pottery vessels, offering tables, and human remains positioned near the burial shafts, material that speaks to routine mortuary practice rather than elite inscriptions or carved narratives. These finds outline a small circle of activity, evidence of families preparing the dead with objects meant to accompany them into the afterlife.

Human bones situated beside coffins point to complex burial treatment, possibly reflecting movement during interment or later disturbance rather than documented funerary meals. Such rites are known from broader Egyptian contexts, yet no animal remains were noted in these tombs, leaving only the architectural setting and grave goods to frame the ritual sequence described by the excavators.

Researchers also noted the tombs’s undecorated walls, a contrast with the painted chambers elsewhere at Qubbet el Hawa. No pigments were preserved here, but comparisons with nearby nobles’ tombs underscore Aswan’s position within long-standing artistic and commercial networks. Every layer, from plain architectural features to modest offering equipment, contributes to a developing portrait of a community whose mortuary habits followed traditions shared across the region.

The excavation team also emphasized the landscape surrounding the tombs, noting how their placement along the slope reflects long-term choices about visibility and access at Qubbet el Hawa. The position above the Nile corridor offered a reminder of the community’s connection to river traffic, quarrying routes, and movement between Aswan and Nubia. Even without decorated chambers, the setting anchors the burials within a broader network shaped by geography, labor, and the rhythms of life along Egypt’s southern frontier.

The Takeaway

The Qubbat al-Hawa discovery is a story of preservation—of memory, artistry, and the human urge to be remembered. As archaeologists sealed the tombs again for conservation, the desert fell quiet once more.

Somewhere behind that rock face lie colors and carvings older than any empire. And thanks to those who found them, they’ll stay that way—safe and still telling stories in the language of eternity. Archeology just got interesting.