The Warrior Who Never Returned: A Bronze Helmet Rises From The Sea After 2,000 Years

Sometimes history doesn’t sit in a museum—it hides beneath the waves. Off the western coast of Sicily, near the Egadi Islands, divers have pulled up something extraordinary: a bronze helmet that likely belonged to a warrior who fought in one of the most decisive naval battles of the ancient world. This helmet, dating back to the 241 BC Battle of the Egadi Islands, isn’t just another relic; it’s a tangible link to the chaotic, bloody final clash that ended the First Punic War and changed the course of Mediterranean history.

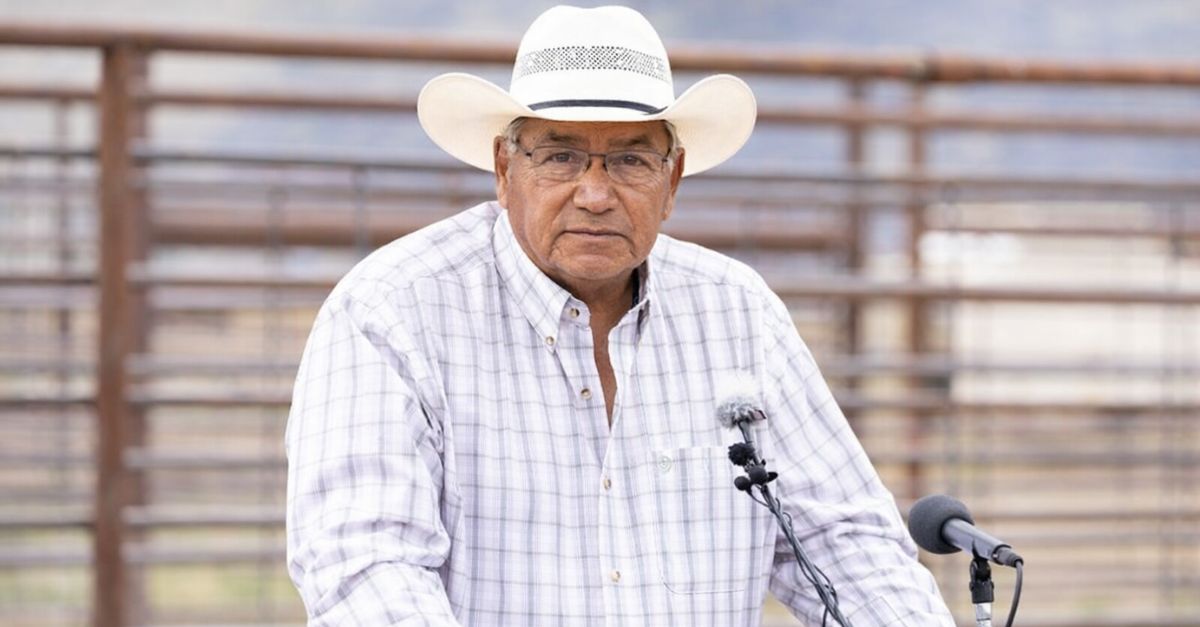

Society for Documentation of Submerged Sites

Society for Documentation of Submerged Sites

A Helmet Emerges From The Deep

Last August, divers working off the coast of western Sicily detected something unusual on the seabed near the Egadi Islands (also spelled Aegates). What appeared initially as a corroded metal lump turned out to be a remarkably well-preserved bronze helmet—complete with cheek guards, of the so-called “Montefortino” type. The site where it was found corresponds with the location of the decisive naval clash that ended the First Punic War in March 241 BC.

Why The Battle Of The Egadi Islands Is A big deal

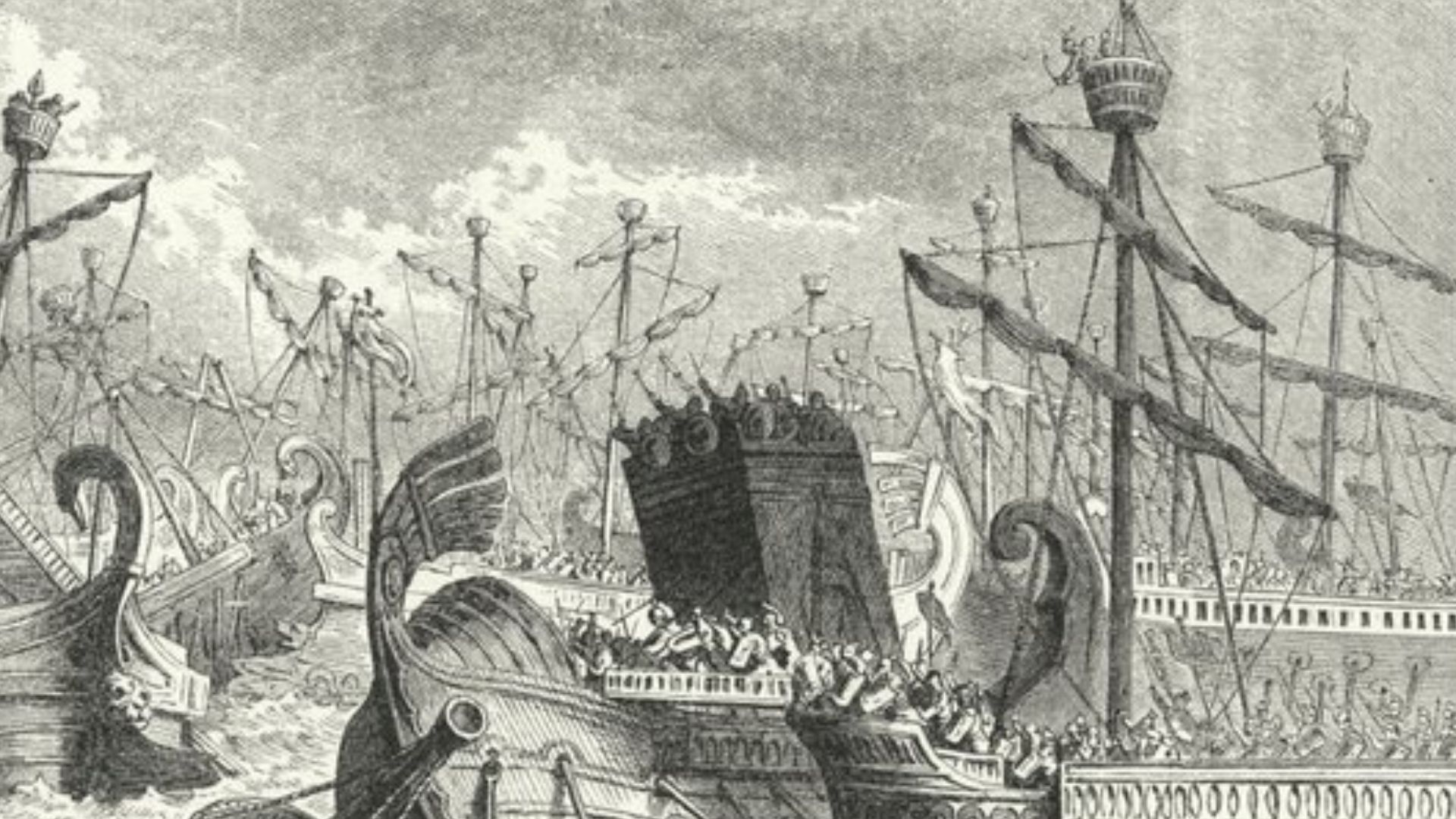

The Battle of the Aegates or Egadi Islands was fought on 10 March 241 BC between the fleets of the Roman Republic and Carthage off Sicily’s west coast. It marked the end of the First Punic War—which had raged for 23 years—and secured Sicily as Rome’s first overseas province. Carthage was forced into major concessions and paid heavy reparations. In short: this battle locked in Roman maritime dominance in the western Mediterranean.

Heinrich Leutemann, Wikimedia Commons

Heinrich Leutemann, Wikimedia Commons

The Underwater Finding Campaign

The helmet was recovered by a team of high-water divers from the Society for the Documentation of Submerged Sites (SDSS) under the supervision of the Sicilian Superintendency of the Sea, the Marine Protected Area of the Egadi Islands, and the local harbor authorities. The area has been under survey for many years and has already yielded dozens of artifacts tied to the battle: bronze rams, weapons, helmets, amphorae.

Description Of The helmet

This isn’t just any helmet. It’s of the Montefortino style: a rounded bronze bowl, a small knob at the crown (for a plume or crest), a short visor, and hinged cheek pieces (paraguances). The cheek guards are still attached—a rare survival. Many similar finds are fragments or missing parts. The condition, and the find-context, make it stand out among First Punic War artifacts.

Dating And Context Of The Helmet

While Montefortino helmets were used from the 4th century BC well into the early Imperial era, the context of this find allows reasonably confident dating to the early 3rd century BC and likely ties it to the 241 BC naval battle. Because the helmet emerged in the seabed scatter of the battle zone, it anchors the object to a known historical event instead of simply typology.

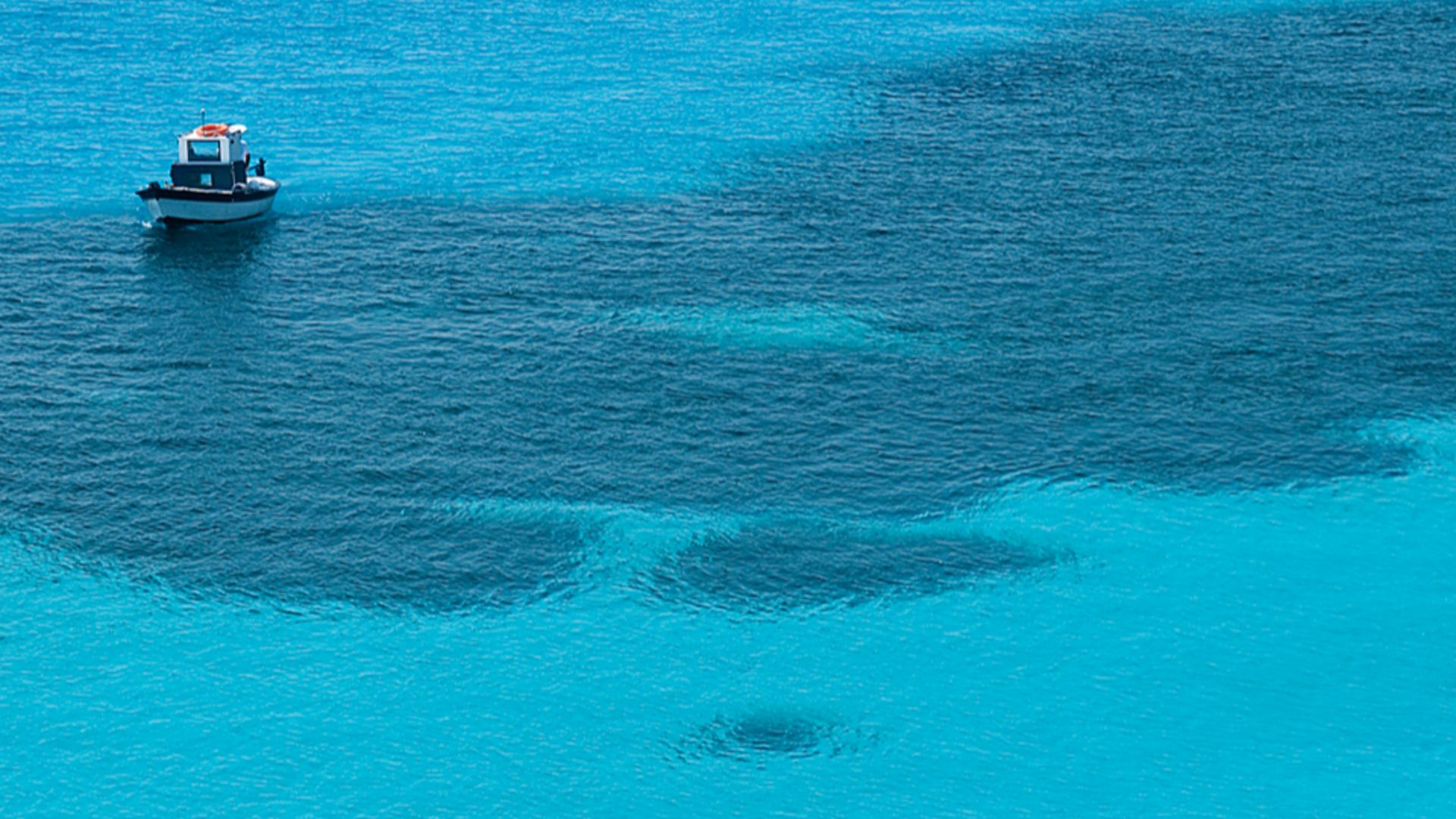

Davide Mauro, Wikimedia Commons

Davide Mauro, Wikimedia Commons

The Site: Where Shipwreck Meets Battlefield

The seabed around the Egadi Islands has revealed warship rams (rostra), helmets, swords, spears, javelins, amphorae and other remains. These finds map a zone where fleets fought, ships sank or were abandoned, and material sank to the bottom. That spatial dimension shifts our thinking: this was maritime combat, not just land war, and the equipment lost tells a story of complexity and scale.

roberto from italy, Wikimedia Commons

roberto from italy, Wikimedia Commons

What The Helmet Tells Us About Ancient Naval Warfare

A helmet, after all, is a personal item, but one found underwater in this context yields clues. It suggests that crew or soldiers aboard warships were equipped much like land-troops. It implies boarding actions, close-quarter fighting, and the possibility of personal equipment lost during the final moments of battle or escape. Because the helmet is so intact, researchers believe it may have been lost only at the last moment—abandoned in haste, sunk with a ship, or jettisoned.

Who Might Have Worn It?

Since Montefortino helmets were standard Roman military issue, the simplest hypothesis is that the wearer was a Roman soldier or marine aboard a Roman warship—and died (or his helmet was lost) during the battle. But there are twists: some helmets found in the same zone may be Carthaginian or mercenary use of Roman-style kit. One scenario: a Roman ship was captured or damaged and abandoned, the helmet lost overboard. Another scenario: a Carthaginian crew forced to wear captured Roman equipment.

Artistosteles, Wikimedia Commons

Artistosteles, Wikimedia Commons

The Preservation Story

The underwater environment both preserves and obscures. Bronze helmets survive, but corrosion and marine encrustation can hide detail. In this case the cheek guards remain and the bowl is intact, which suggests a rapid sinking and burial in anaerobic seabed conditions that limited breakdown. Recovery involved careful scuba operations, documentation, CT scans for internal residues, and conservation treatments.

Aligning The Artifact With The Battle Narrative

According to ancient historian Polybius, Rome’s fleet under the command of Gaius Lutatius Catulus sailed out, engaged Carthage’s fleet, and sank or captured many Carthaginian ships. The material remains off the Egadi Islands—like the helmets and rams—support that narrative by locating a zone dense with battle-gear. That convergence of text and archaeology strengthens our reconstruction of the battle.

Why The Helmet Matters

Objects like this helmet are rare: one complete example in a known naval battle zone. It helps fill gaps: what gear soldiers wore at sea, what kinds of helmets were in use aboard warships, how losses happened. It brings the human dimension of ancient naval warfare into sharper focus—not just big fleets and rams, but the man (or marine) under the helmet.

Insights Into Shipboard Fighting

Naval warfare in the ancient Mediterranean was complex: ramming, boarding, missile fire, grappling. A bronze helmet suggests close-in fighting where personal protection mattered. It reinforces interpretations that boarding actions were central in this war and that ships carried fighters ready to engage hand-to-hand. The helmet thus ties equipment to tactics.

The Discovery In The Broader Archaeological Campaign

This find isn’t isolated. The campaign around the Egadi Islands has pulled up over twenty warship rams, dozens of helmets and amphorae, and weapon scatters. All this data creates a dense web of material culture pointing to the First Punic War’s naval dimension—something traditionally less visible than land battles.

Alessio Milan, Wikimedia Commons

Alessio Milan, Wikimedia Commons

Researchers’ Hypotheses About The Helm’s Story

Scholars are proposing several possibilities: the helmet belonged to a Roman mariner or marine, lost during the crushing Roman victory; it may have been on a captured Roman vessel crewed by Carthaginians and lost in the retreat; metallurgical signatures might reveal where the bronze came from or whether it was repaired—indications of supply networks or unit identity; its exact position on the sea-floor might tie it to a specific wreck, giving ship type and perhaps even which side it fought on.

What It Says About Roman And Carthaginian Equipment

The Montefortino helmet design highlights Rome’s adoption of Celtic-style helmets. This find underlines that even in naval service, Roman troops used such helmets. It raises questions about whether Carthaginians or mercenaries used similar gear and how standardization spread across navies.

Ángel M. Felicísimo from Mérida, España, Wikimedia Commons

Ángel M. Felicísimo from Mérida, España, Wikimedia Commons

Linking To The Wider War Story

The First Punic War was Rome’s first major overseas conflict and built its reputation as a naval power. The Egadi battle ended that war, and every artifact from the site connects to that pivotal moment. This helmet becomes more than a relic—it’s a witness to the dawn of Roman dominance over the Mediterranean.

Conservation And Future Research

After recovery, the helmet underwent conservation and CT scanning to examine metal composition and any residues of fabric or organic remains. Future research hopes to compare it with other Egadi finds (helmets, rams) to build profiles of ship types, crew equipment, and even personal identity if inscriptions or repair marks are found.

Renato Alongi, Wikimedia Commons

Renato Alongi, Wikimedia Commons

Public Engagement & Cultural Heritage

Regional authorities in Sicily emphasized the find’s importance for cultural identity and tourism: the Egadi Islands, they say, guard the memory of a world-changing battle. The helmet is now seen not just as an archaeological curiosity but as a symbol of Sicily’s layered maritime past.

Looking Ahead

There’s more to come. As underwater archaeology advances, more shipwrecks, more gear, more human stories will surface. Each object adds texture and nuance. This helmet—one of the best-preserved yet—invites us to dive deeper into how ancient men fought on wood, bronze, and waves.

Final Thoughts

When you imagine ancient naval warfare you often picture massive fleets, but this helmet reminds us that beneath the oars and rams were individuals—fighters with fears, courage, and duty. 2,000 years later, one of their helmets rises from the sea, and with it, a fragment of their story.

You May Also Like: