Timeframes Finally Make Sense

Strange clues from centuries ago keep resurfacing, and researchers now have a tool sharp enough to make sense of them. Archaeologists are turning to advanced X-ray dating to uncover when early colonizers shaped the iron they left behind.

Iron Objects That All Look Alike

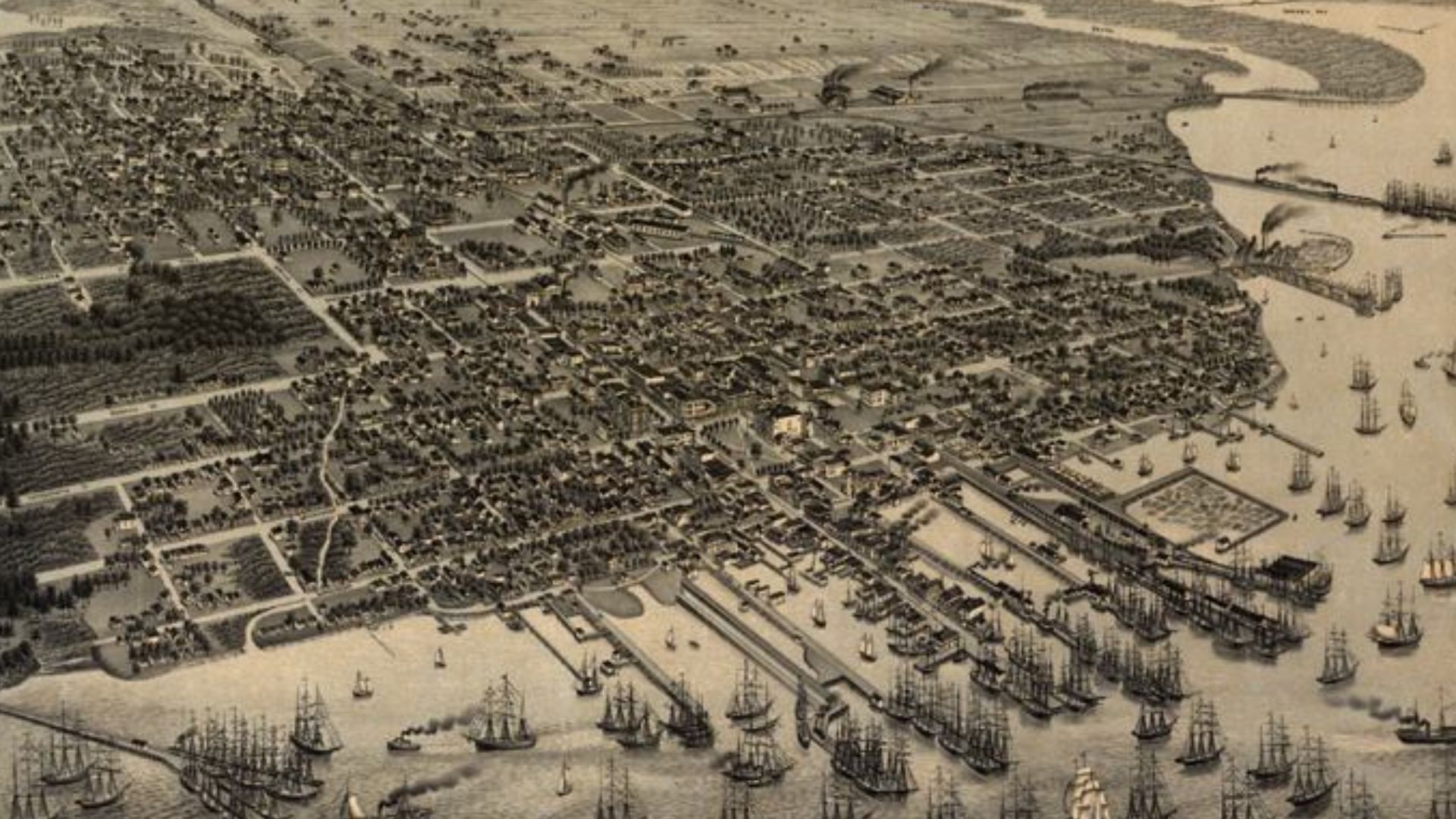

Iron pieces from Spanish expeditions resemble one another so closely that archaeologists struggle to tell which journey they came from. Similar nails, tools, and fragments blur timelines. That’s why it’s difficult to map precise routes through early North American scenes and Indigenous settlements.

Why Finding Spanish Iron Matters

Because written records are incomplete, archaeologists rely heavily on Spanish-made objects. Iron was carried in bulk and appears frequently at Indigenous sites, serving as one of the clearest material traces of early colonial movements through regions now difficult to map historically.

Roman Fekonja, Wikimedia Commons

Roman Fekonja, Wikimedia Commons

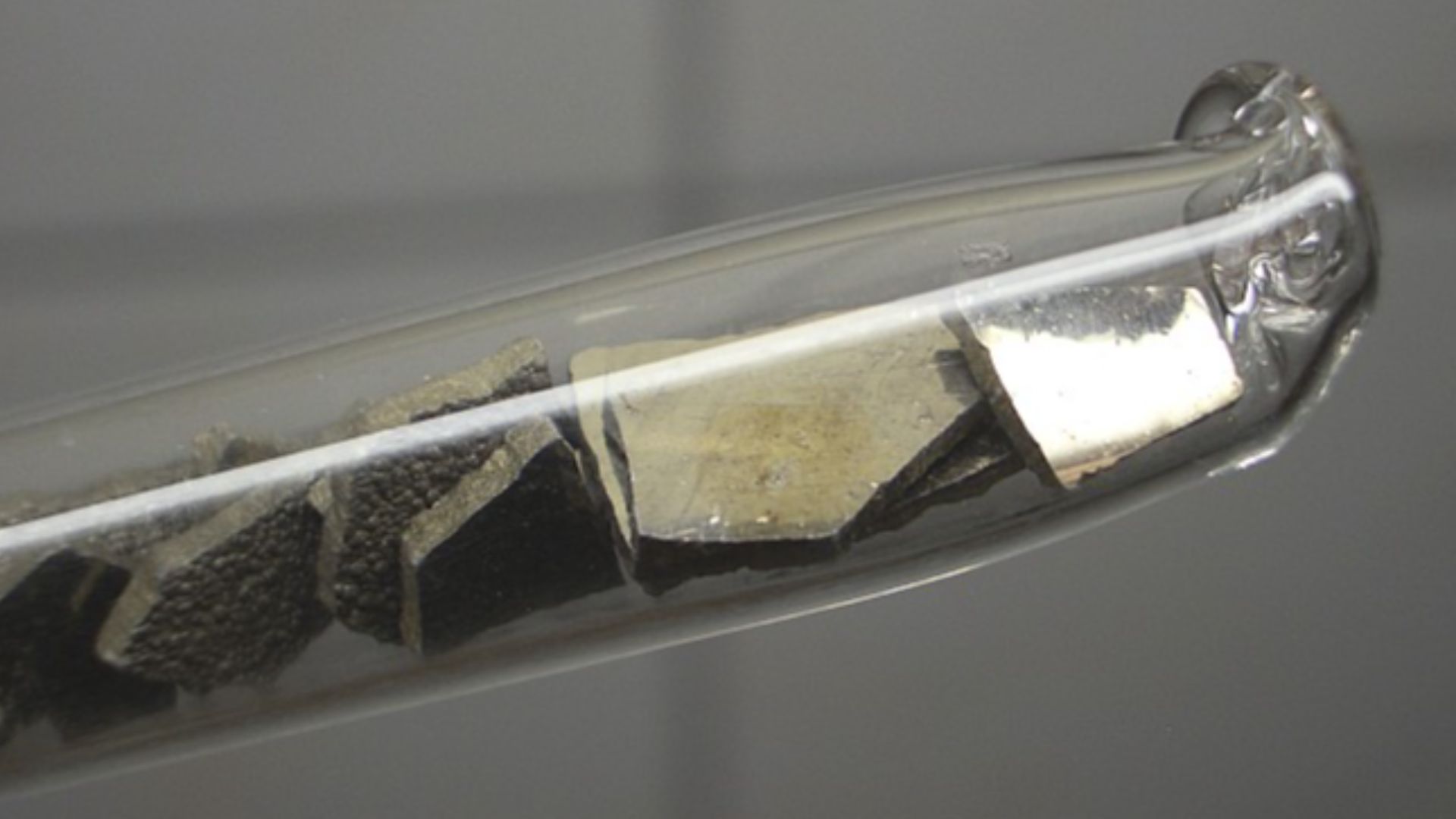

Nails That Reveal Nothing By Sight

Wrought-iron nails from the 1500s look nearly identical to those from the 1600s. Their uniformity makes visual sorting impossible, which explains why thousands of recovered nails end up bagged and forgotten during excavations that cannot initially determine their origin.

Countless Iron Objects The Spanish Hauled Along

Expeditions carried massive amounts of iron: nails, horseshoes, spearheads, armor pieces, and tools. Blacksmiths traveled with them to repair items during long treks. Unfortunately, these pieces are stylistically uniform. They prevent easy identification without laboratory analysis to reveal chemical fingerprints.

John Martin PERRY, Wikimedia Commons

John Martin PERRY, Wikimedia Commons

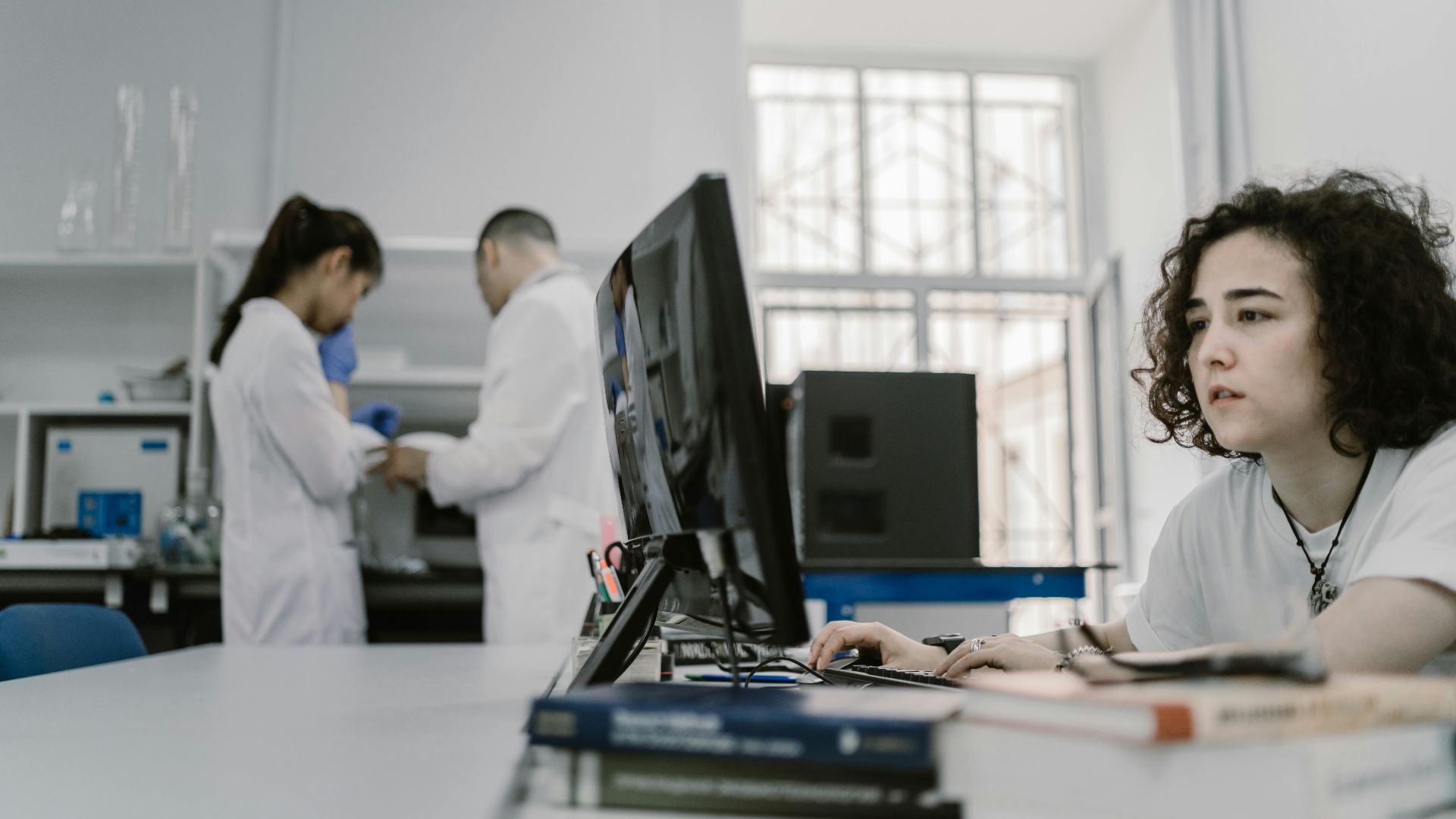

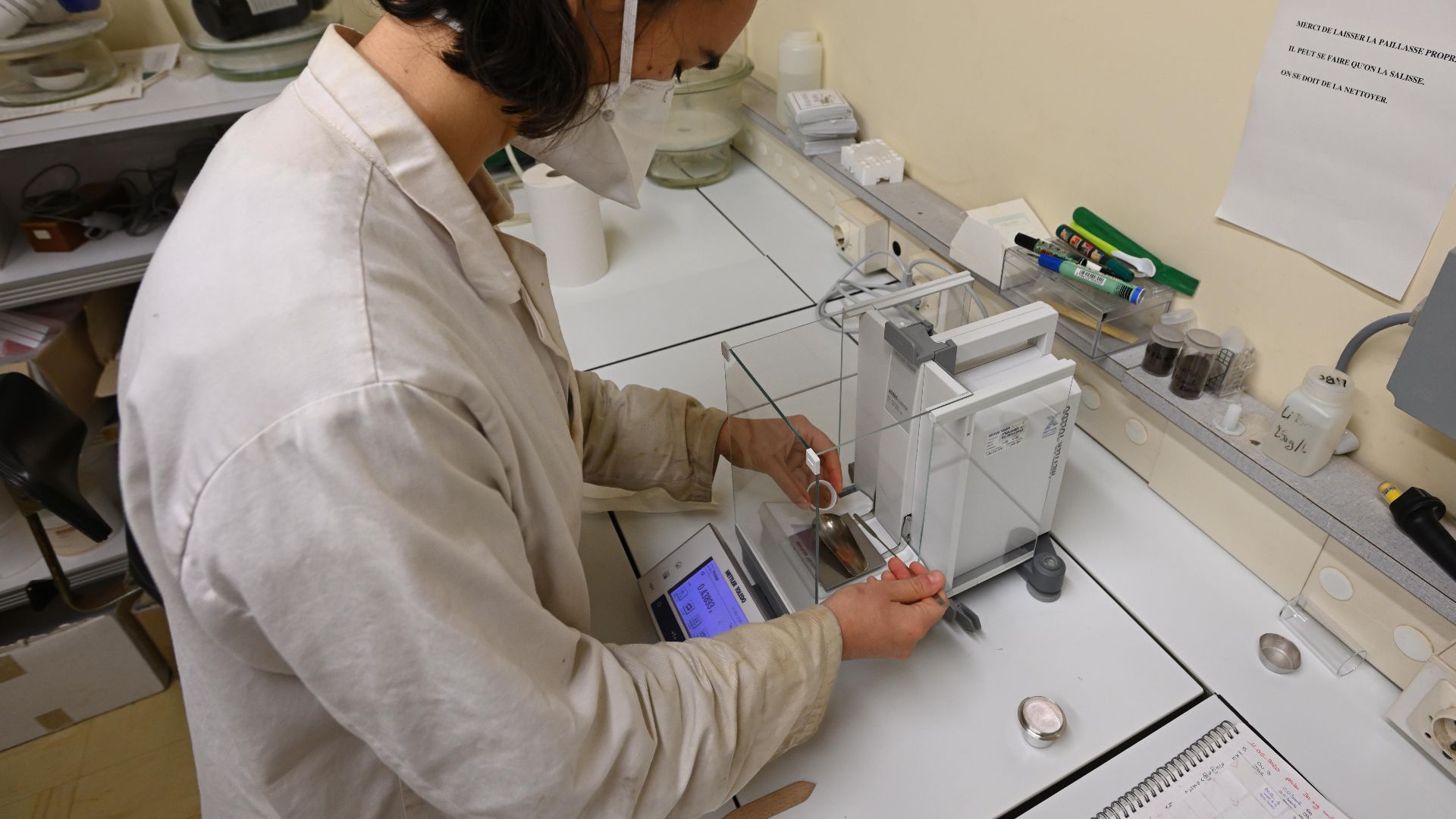

Using X-Ray Fluorescence To Sort The Past

Researchers who applied X-ray fluorescence to four centuries of iron artifacts, including Charles Cobb and Lindsay Bloch, uncovered chemical signatures linked to specific periods. Subtle shifts in purity and trace elements now provide a reliable means of separating once indistinguishable objects.

LinguisticDemographer at English Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

LinguisticDemographer at English Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

Iron Impurities Hold Clues

Iron becomes nearly pure during forging, but not completely. Trace elements like copper or manganese remain. Their proportions reflect where the original ore was mined and how much processing it underwent, and this creates chemical patterns that can indicate origin or approximate timeframe.

Mervat Salman, Wikimedia Commons

Mervat Salman, Wikimedia Commons

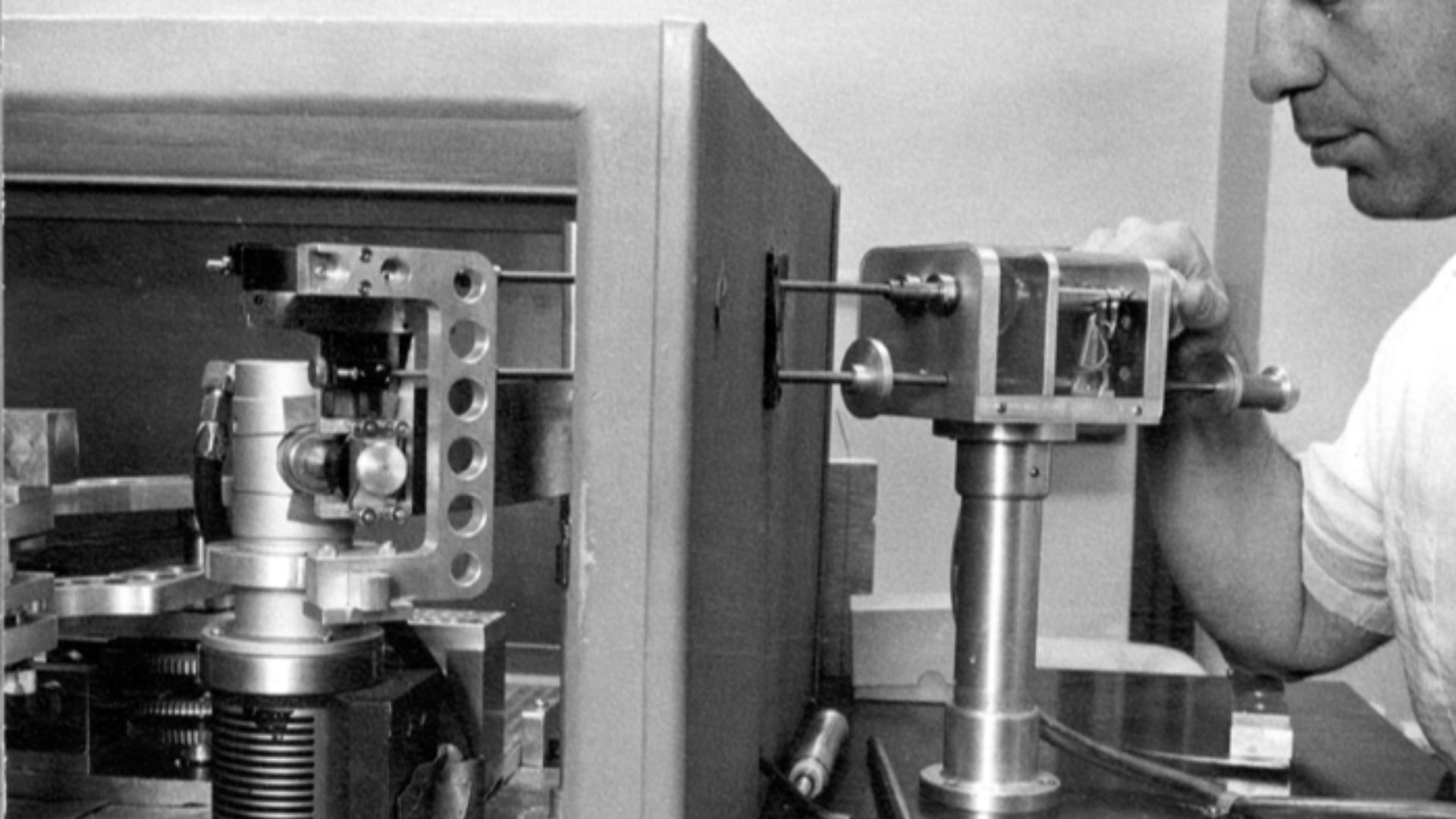

Metals Respond Perfectly To X-Ray Study

Since dense materials like iron produce clear X-ray signals, they are ideal for fluorescence analysis. The technique captures elemental compositions instantly, allowing experts to compare artifacts efficiently and identify differences invisible to the eye during standard excavation or cataloging.

Bill Branson (Photographer), Wikimedia Commons

Bill Branson (Photographer), Wikimedia Commons

X-Rays Are Changing What Was Possible

A new study led by Charles Cobb and Lindsay Bloch shows that X-ray readings can reveal microscopic differences invisible to the eye. These chemical variations may help researchers assign artifacts to specific decades. The approach could finally resolve long-standing identification problems and reshape interpretations of the early colonial movement.

Stephane Lesbats, Wikimedia Commons

Stephane Lesbats, Wikimedia Commons

A Promising Method That Needs More Data

Preliminary results are strong, but we still need a larger dataset before declaring the method foolproof. Differences between expeditions separated by only decades appear detectable, yet additional samples are essential to confirm how reliably X-ray readings distinguish overlapping Spanish campaigns.

File Upload Bot (Magnus Manske), Wikimedia Commons

File Upload Bot (Magnus Manske), Wikimedia Commons

European Artifacts Outside Florida Multiply

In recent years, finds of European objects at Indigenous sites outside Florida have surged. The increase raises new questions about which expeditions they belonged to and creates pressure for better analytical tools that can sort artifacts from overlapping Spanish ventures.

Abraham Ortelius, Wikimedia Commons

Abraham Ortelius, Wikimedia Commons

An Expert Who Shaped The Method

Lindsay Bloch, widely respected for her work on X-ray spectrometry in archaeology, led much of the scanning. Her earlier guidelines helped establish how researchers across the field use this technology to give the current project a solid scientific foundation.

Son of Groucho from Scotland, Wikimedia Commons

Son of Groucho from Scotland, Wikimedia Commons

A Proof Of Concept Tested Broadly

The team included artifacts from colonies, missions, battle sites, British forts, and plantations. By choosing iron from varied places and centuries, they could test whether chemical differences were strong enough to serve as consistent markers across time and geography.

Diego Ruschel, Wikimedia Commons

Diego Ruschel, Wikimedia Commons

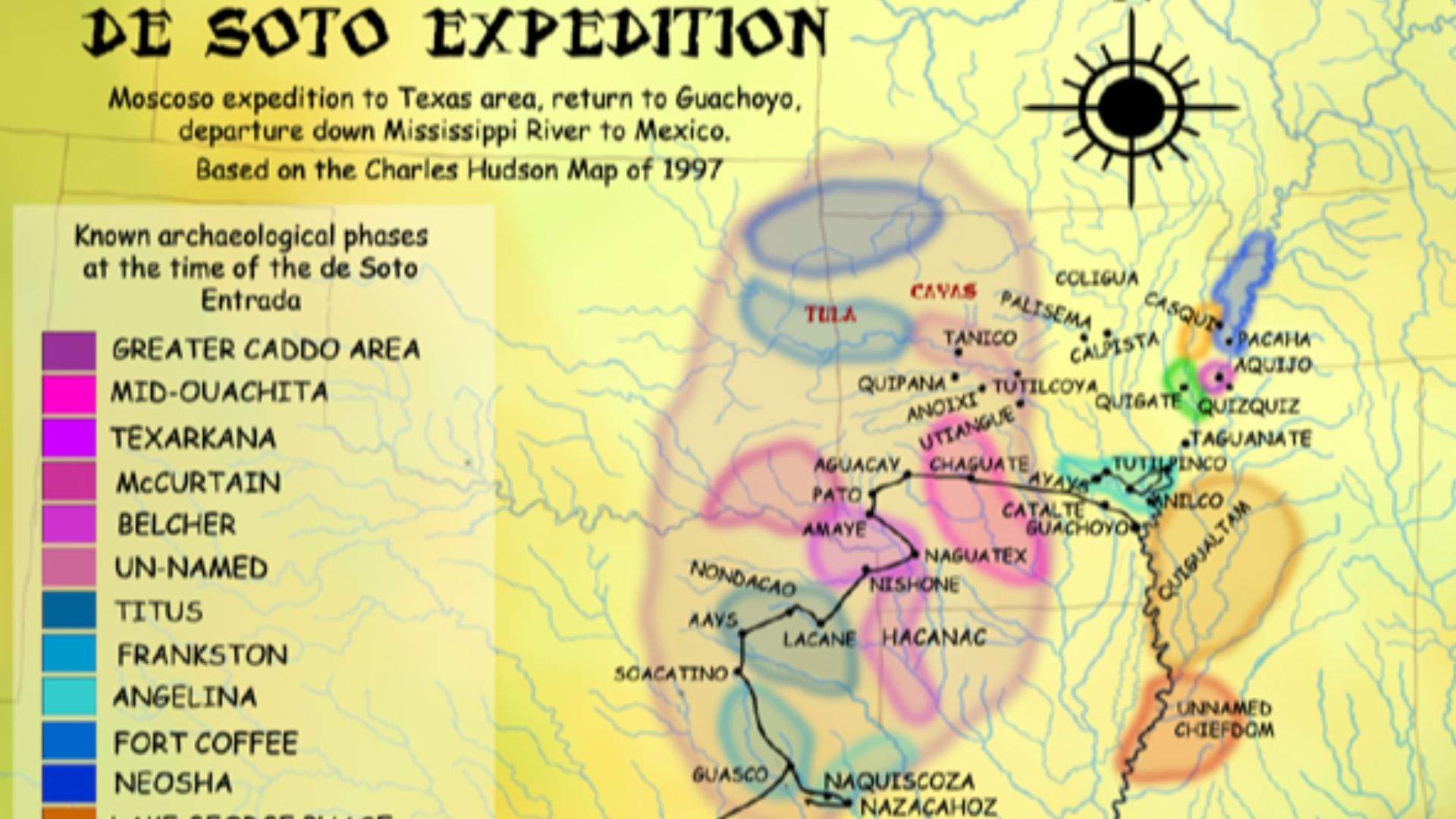

Searching For Evidence At Marengo

The Marengo complex contains artifacts likely tied to major battles. De Soto passed through the area and left behind supplies, but another expedition under de Luna arrived later and abandoned similar iron. That overlap creates uncertainty that chemical analysis hopes to resolve.

MariyaShubina, Wikimedia Commons

MariyaShubina, Wikimedia Commons

Two Expeditions With Similar Fates

Although De Soto and de Luna visited many of the same regions and endured similar hardships, their supply chains differed. De Soto sourced gear from Spain, while de Luna relied on New Spain. Those contrasting origins may leave detectable elemental differences in the surviving iron.

Heironymous Rowe (talk), Wikimedia Commons

Heironymous Rowe (talk), Wikimedia Commons

Earlier Tests Offered Tempting Clues

A 2013 comparison of Pensacola and Tallahassee iron suggested differences between de Luna and de Soto artifacts. The results were promising but too limited to confirm patterns confidently. The new study expands on that foundation using a much larger and more varied dataset.

Urban~commonswiki, Wikimedia Commons

Urban~commonswiki, Wikimedia Commons

Why Overlapping Supply Chains Created Confusion

Spanish expeditions sourced iron from different places, yet many pieces ended up looking nearly identical after forging and reuse. These supply-chain overlaps introduced decades of misidentification. X-ray fluorescence cuts through that noise by revealing elemental fingerprints that reflect each expedition’s unique provisioning network.

Gaston, after Robert Dodd, Wikimedia Commons

Gaston, after Robert Dodd, Wikimedia Commons

How Reforging Altered But Didn’t Erase Chemical Signals

Spanish blacksmiths frequently reforged broken tools into new ones, a practice that blurred stylistic clues. However, as aforementioned, reforging can’t eliminate all trace elements locked into the metal during smelting. Those surviving chemical signatures give archaeologists a stable marker that endures through centuries of reuse and repurposing.

Scanning The Assemblage For Answers

Bloch used a handheld spectrometer to assess each piece’s chemical fingerprint. The scans revealed consistent differences in impurity types and iron purity across centuries. They demonstrated that even small traces of certain elements could reliably signal when an object was made.

U.S. Air Force photo/Airman 1st Class Devante Williams, Wikimedia Commons

U.S. Air Force photo/Airman 1st Class Devante Williams, Wikimedia Commons

Manganese, Bismuth, And Other Telltale Elements

Specific impurities tracked neatly with particular centuries. Some sixteenth-century items contained manganese, while eighteenth- and nineteenth-century artifacts showed bismuth. Other elements appeared mainly in late sixteenth and seventeenth-century iron. All of them give archaeologists a timeline based on recurring elemental patterns.

Iron Quality Rose And Fell Over Time

Mid-sixteenth-century iron was highly pure, especially in horseshoes. In later centuries, quality declined, with increased impurities and varied elemental signatures. Quality improved again in subsequent periods, but never matched the exceptional purity of the earliest Spanish expeditions.

Ethan Doyle White, Wikimedia Commons

Ethan Doyle White, Wikimedia Commons

What The Marengo Iron Suggests Now

The chemical profile of iron from Marengo most closely aligns with de Soto’s expedition, though the team stresses caution. More confirmed samples are needed before claiming certainty, since overlapping expeditions and shared materials complicate conclusions without a broader reference database.

Why Researchers Need A Larger Reference Set

To identify artifacts confidently, archaeologists require samples firmly tied to specific expeditions. These known pieces would serve as benchmarks. Without a reference library, interpretations remain preliminary, and distinguishing between closely spaced Spanish journeys remains challenging.

X-Ray Data Is Only The Starting Point

Although X-ray fluorescence produces quick insights, it lacks the precision needed for definitive sourcing. Isotopic analysis offers deeper detail by examining atomic structures, but it is costly. Researchers hope future funding will allow them to apply this more advanced method.

Bobjgalindo, Wikimedia Commons

Bobjgalindo, Wikimedia Commons

The Next Phase Of Unlocking The Past

A proposed grant would support isotopic work that could finally pinpoint the origins of disputed artifacts with high accuracy. Combining X-ray and isotopic results may rewrite major sections of colonial history by mapping Spanish routes more clearly than documents ever could.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Wikimedia Commons

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Wikimedia Commons