An Odd Absence

Most of this ancient burial ground followed clear rules. Status meant location. That’s why one oddly unused space caught attention and quietly challenged what researchers thought they understood about how the area was planned.

Mouad Mabrouk, Pexels, Modified

Mouad Mabrouk, Pexels, Modified

Giza Plateau

About 13 kilometers southwest of Cairo's center sits a limestone plateau that rises roughly 60 meters above sea level, housing humanity's most enduring architectural achievements. The Giza Plateau forms the northernmost section of a massive 160-square-kilometer pyramid field stretching along the Western Desert's edge.

Morhaf Kamal Aljanee, Wikimedia Commons

Morhaf Kamal Aljanee, Wikimedia Commons

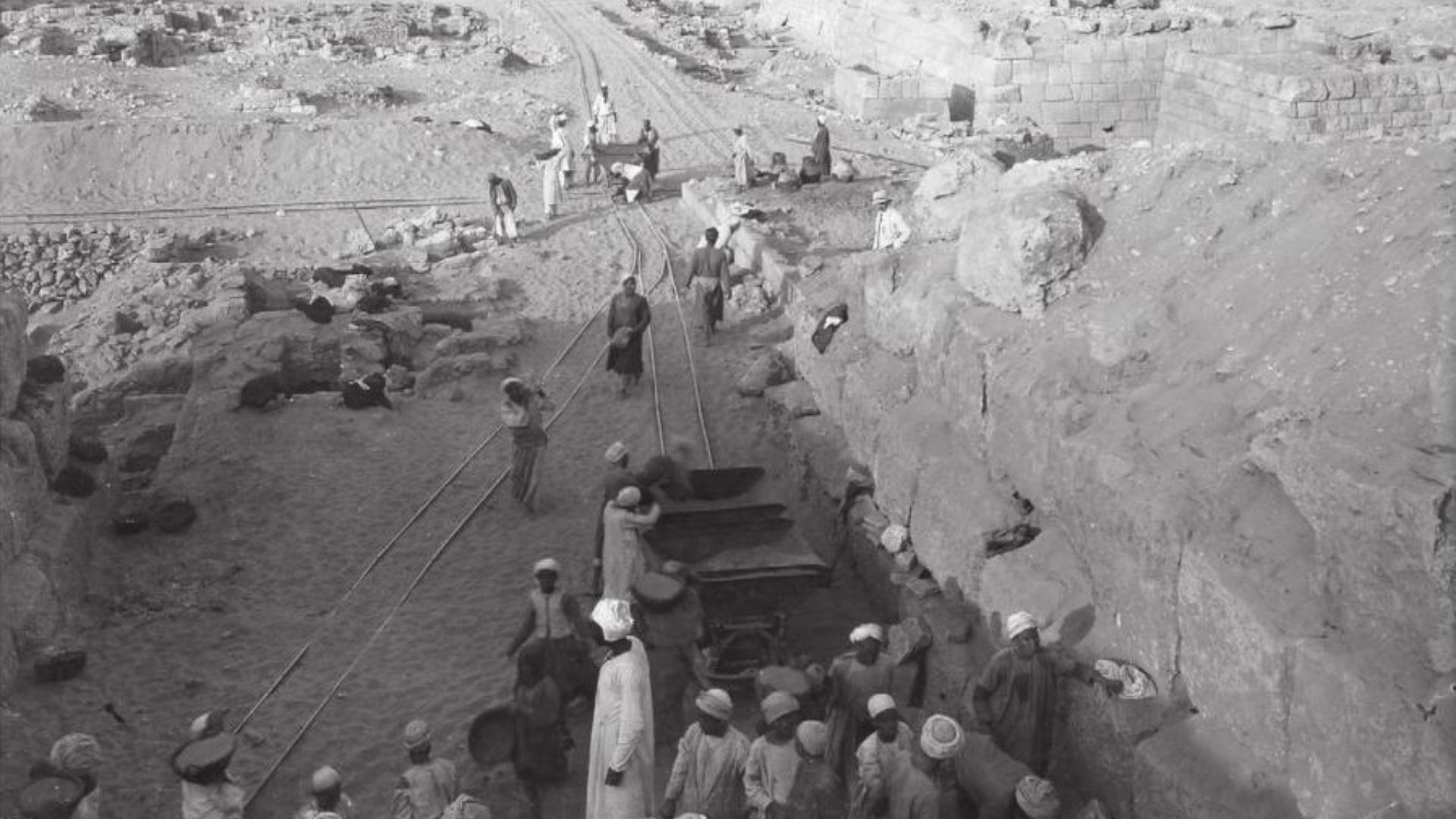

Western Cemetery

The largest Old Kingdom burial ground at Giza sprawls to the west of Khufu's Great Pyramid. Unlike its eastern counterpart, reserved for Khufu's closest relatives, this necropolis became the final resting place for high-ranking noblemen, court dignitaries, and pyramid construction overseers who weren't directly part of the royal bloodline.

George Andrew Reisner Jr. (November 5, 1867 – June 6, 1942), Wikimedia Commons

George Andrew Reisner Jr. (November 5, 1867 – June 6, 1942), Wikimedia Commons

Ancient Necropolis

Khufu initiated this methodical cemetery development during the Fourth Dynasty, assigning specific tomb locations to officials while his massive pyramid rose skyward. The necropolis remained active for centuries, with burials continuing through the Fifth and Sixth Dynasties as priests, viziers, and administrative families added their own monuments to the sacred landscape.

George Andrew Reisner, Wikimedia Commons

George Andrew Reisner, Wikimedia Commons

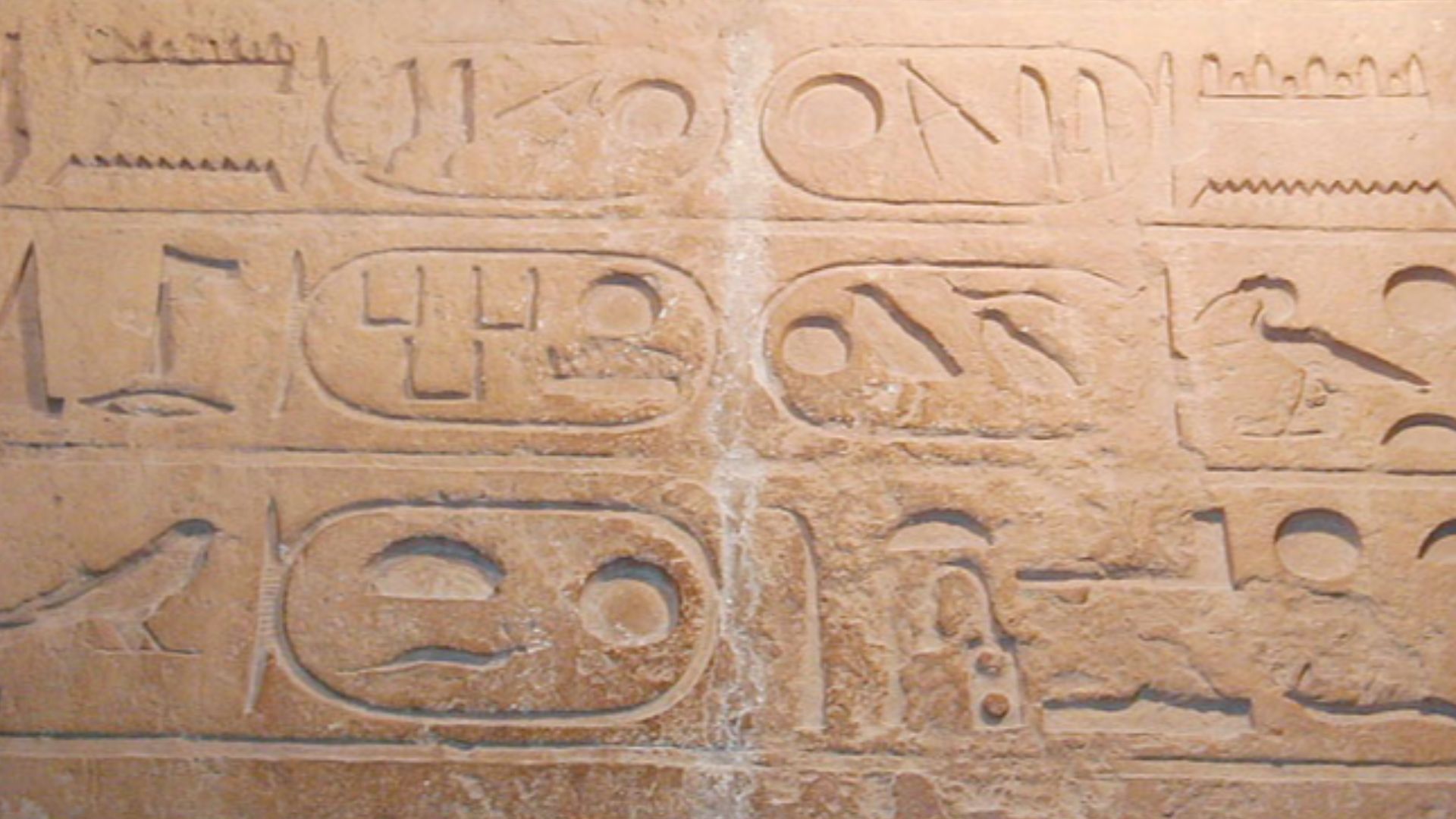

Mastaba Tombs

These rectangular structures with flat roofs earned their Arabic name "mastaba," meaning "bench," due to their distinctive shape resembling stone benches scattered across the desert landscape. A typical mastaba featured an above-ground chapel constructed from limestone or mudbricks, beneath which vertical shafts descended deep into bedrock.

Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, Wikimedia Commons

Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, Wikimedia Commons

Royal Burials

Proximity to the king mattered immensely in ancient Egypt's concept of the afterlife, making burial near Khufu's pyramid the ultimate status symbol for Fourth Dynasty elites. The Western Cemetery housed high-ranking elites, including possible princes or royal relatives like Hemiunu (vizier and likely pyramid architect).

Einsamer Schutze, Wikimedia Commons

Einsamer Schutze, Wikimedia Commons

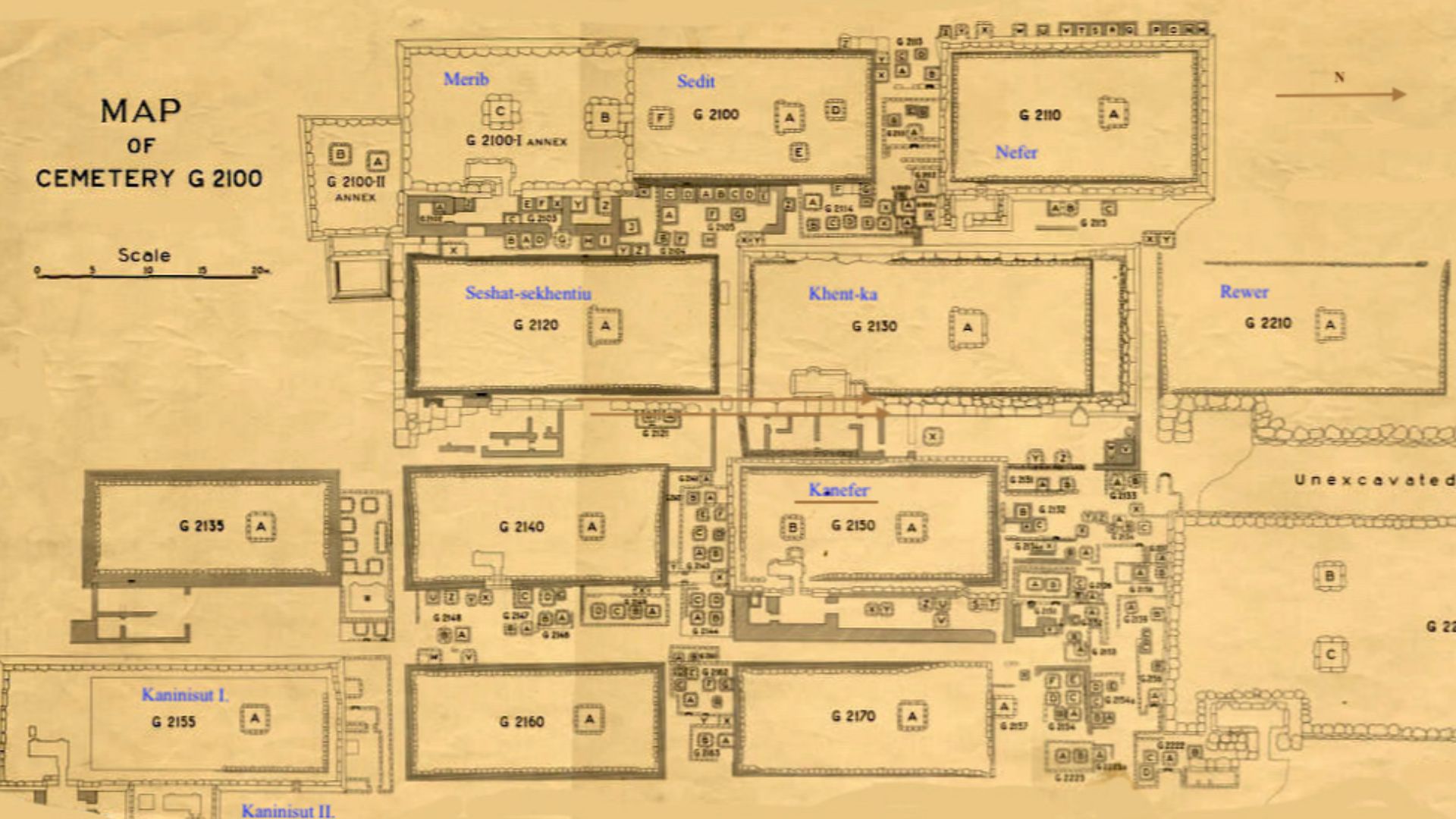

Blank Area

Right in the middle of the densely populated Western Cemetery, archaeologists had long puzzled over a conspicuously empty rectangular patch measuring roughly 80 meters east to west and 110 meters north to south. No above-ground structures marked this flat, vacant space despite its prime location beside the pyramids of Khufu.

Unexplored Ground

Despite Giza being among the most extensively excavated archaeological sites on Earth, with formal investigations beginning in the 19th century and continuing through systematic 20th-century expeditions. The great archaeologists George Reisner, Hermann Junker, and Selim Hassan produced many monographs documenting their Giza excavations between 1903 and the 1960s.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Hidden Secrets

The Western Cemetery's puzzle deepened when researchers considered the area's context: every surrounding location teemed with high-status burials. Egyptian funerary practices during the Old Kingdom emphasized filling available burial ground near royal monuments, with officials competing for the most prestigious locations closest to their pharaoh.

Jon Bodsworth, Wikimedia Commons

Jon Bodsworth, Wikimedia Commons

International Collaboration

Researchers from Japan's Higashi Nippon International University and Tohoku University joined forces with Egypt's National Research Institute of Astronomy and Geophysics to investigate what conventional excavation had long overlooked. This cross-continental partnership brought together expertise in advanced geophysical survey technology with deep knowledge of Egyptian archaeology and geology.

James Byrum from Nowhere, Wikimedia Commons

James Byrum from Nowhere, Wikimedia Commons

Tohoku University

Leading the research effort, Professor Motoyuki Sato from Tohoku University's Center for Northeast Asian Studies brought decades of experience in ground-penetrating radar applications to archaeological contexts. Sato had previously applied GPR surveys in various archaeological contexts, including sites in Japan where uneven topography and small-scale remains demanded precision imaging capabilities.

ChampagneFight, Wikimedia Commons

ChampagneFight, Wikimedia Commons

Egyptian Partnership

Egypt's National Research Institute of Astronomy and Geophysics contributed critical local expertise and regulatory access. The NRIAG team had previously conducted successful geophysical surveys at other Egyptian sites, including Saqqara, Dahshur, and various temple complexes throughout the Nile Valley.

Vyacheslav Argenberg, Wikimedia Commons

Vyacheslav Argenberg, Wikimedia Commons

Geophysical Survey

The team deployed non-invasive imaging techniques that allow archaeologists to map underground features without breaking ground. Modern geophysical archaeology has changed the field since the 1980s, enabling scientists to detect buried structures, identify void spaces, map subsurface stratigraphy, and pinpoint excavation targets with remarkable precision.

Radar Technology

Ground-penetrating radar works by transmitting high-frequency radio waves into the earth and measuring how long those electromagnetic pulses take to bounce back after encountering subsurface discontinuities. When radar waves hit buried objects, structural boundaries, or void spaces, they reflect back to surface-mounted antennas at different speeds.

Arc Geodesy Pvt Ltd, Wikimedia Commons

Arc Geodesy Pvt Ltd, Wikimedia Commons

GPR Method

The Tohoku-NRIAG team used GPR equipment to detect variations in dielectric constants between sand, limestone, air voids, and other materials. Their surveys involved systematically moving radar antennas across the blank area in carefully planned grid patterns, collecting data at regular intervals to build comprehensive three-dimensional models of subsurface structures.

Electrical Resistivity

Complementing the GPR survey, electrical resistivity tomography measures how easily electric current flows through subsurface materials by inserting electrode arrays into the ground and recording voltage variations. Different materials conduct electricity at vastly different rates.

2021–2023 Investigation

The research team conducted their initial survey in 2021, identifying a large anomaly at the northern end of the blank area that warranted a detailed follow-up investigation. Over the next two years, they methodically expanded their survey coverage, running additional GPR profiles in multiple directions.

The Official CTBTO Photostream, Wikimedia Commons

The Official CTBTO Photostream, Wikimedia Commons

Mysterious Anomaly

The combined GPR and ERT data revealed a two-part subsurface structure, unlike natural geological formations, which typically show irregular shapes and gradual boundaries. The shallow component's distinct L-shaped plan measured approximately 10 meters (north–south) by 15 meters (east–west) overall.

The Official CTBTO Photostream, Wikimedia Commons

The Official CTBTO Photostream, Wikimedia Commons

L-Shaped Structure

Professor Motoyuki Sato emphasized the significance of the structure's geometry, stating that natural geological processes simply cannot create L-shaped formations with such sharp, defined corners and straight edges. The radar profiles showed clear boundaries where this feature's material properties contrasted sharply with surrounding deposits.

The Charles Machine Works, Wikimedia Commons

The Charles Machine Works, Wikimedia Commons

Shallow Feature

The uppermost L-shaped structure sits just 0.5 to 2 meters below the surface, placing it at depths where erosion, wind-blown sand accumulation, and millennia of environmental change could easily have concealed it from visual detection. GPR analysis showed this feature had been filled with sand.

The Official CTBTO Photostream, Wikimedia Commons

The Official CTBTO Photostream, Wikimedia Commons

Deeper Structure

Electrical resistivity tomography detected the more enigmatic anomaly lying 3.5 to 10 meters below ground surface, well beyond GPR's effective penetration depth in Giza's dense limestone environment. This deeper feature's "highly electrically resistive" signature intrigued researchers because such readings could indicate several possibilities.

Ekrem Canli, Wikimedia Commons

Ekrem Canli, Wikimedia Commons

Backfilled Sand

Sand infilling the shallow L-shaped structure told researchers this wasn't a natural cavity but rather a deliberately constructed feature. The backfill material's radar signature differed noticeably from the undisturbed desert substrate surrounding the anomaly, indicating human intervention rather than gradual natural accumulation over centuries.

Possible Entrance

The research team hypothesized that the shallow L-shaped structure may have served as an entryway providing access to the deeper, larger structure detected by electrical resistivity tomography. Ancient Egyptian tomb architecture frequently employed entrance shafts, descending passages, and corridor systems connecting surface-level access points to underground burial chambers.

Dennis G. Jarvis, Wikimedia Commons

Dennis G. Jarvis, Wikimedia Commons

Limestone Walls

Limestone, quarried abundantly from the Giza Plateau itself during pyramid construction, produces distinctive electrical resistivity signatures that differ markedly from sand, soil, or air-filled voids. The anomaly's sharp, well-defined boundaries visible in both GPR and ERT data suggested constructed surfaces rather than irregular natural formations.

Archaeological Significance

This discovery represents more than just another tomb at the world's most excavated archaeological site—it demonstrates that even intensively studied ancient landscapes still harbor hidden secrets awaiting technological revelation. Beyond its individual importance, this finding validates the continued application of advancing geophysical technologies to "exhausted" sites.

Robster1983 at English Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

Robster1983 at English Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons