Rewriting Canadian History

In a groundbreaking study in the Chilcotin region of British Columbia, archaeologists and Indigenous researchers have uncovered over 70 pre-historic Secwépemc Nation settlements. They include pit houses that date over 4,000 years—older than the Egyptian pyramids. Not only does the find shed light on advanced First Nations architecture, but it also directly refutes colonial reports of Indigenous land occupation and permanence.

A Remarkable Discovery In The Chilcotin

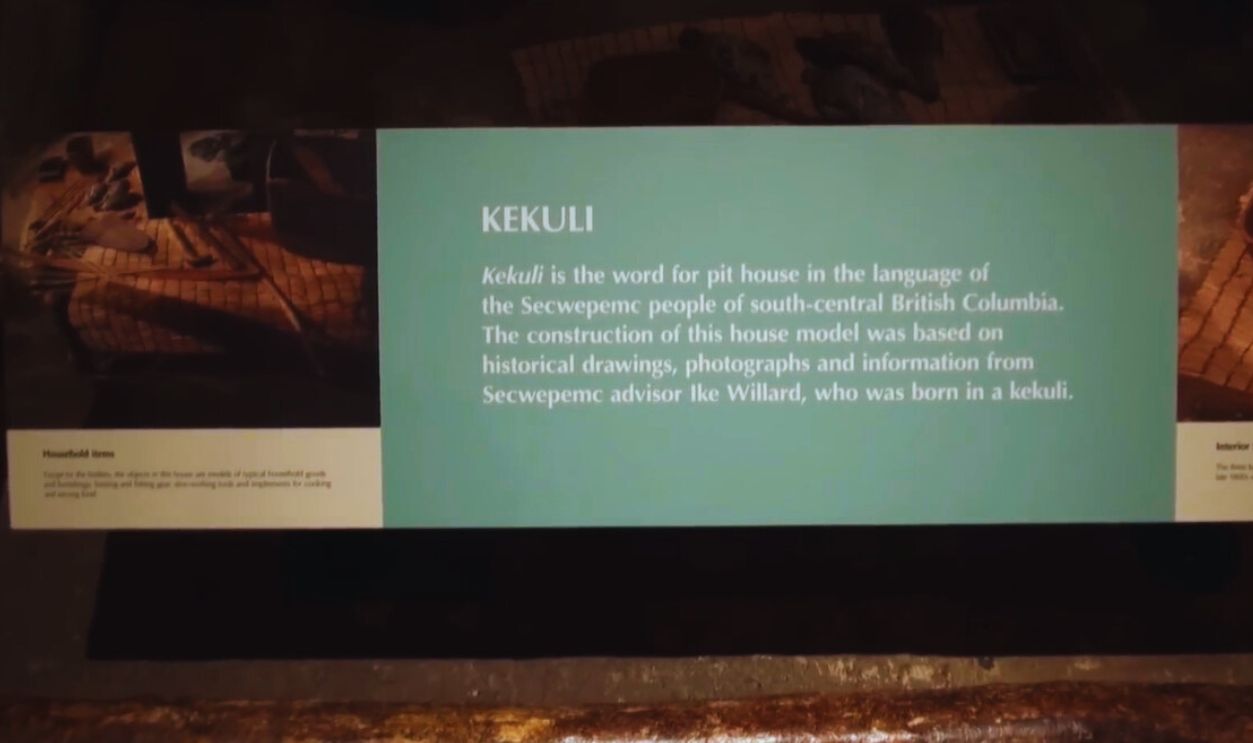

Scientists conducting a cultural heritage assessment in remote Tŝilhqot'in territory found over 70 ancient Secwépemc settlements, an historic discovery. They include many kekuli—underground pit houses—thousands of years old. Most of the structures are surprisingly intact, providing extraordinary insight into sophisticated housing techniques used by early First Nations residents.

David Stanley from Nanaimo, Canada, Wikimedia Commons

David Stanley from Nanaimo, Canada, Wikimedia Commons

The Location: Tŝilhqot'in Plateau

The Chilcotin Plateau, or Tŝilhqot'in Plateau, is a rocky and ecologically diverse area in interior British Columbia. High plateaus, river canyons, and dense forest make the area remote but resource-rich. The area is home to several distinct Indigenous nations, including the Secwépemc and Tŝilhqot'in, who have occupied the area for thousands of years.

Sebastien Launay, Wikimedia Commons

Sebastien Launay, Wikimedia Commons

What Are Pit Houses?

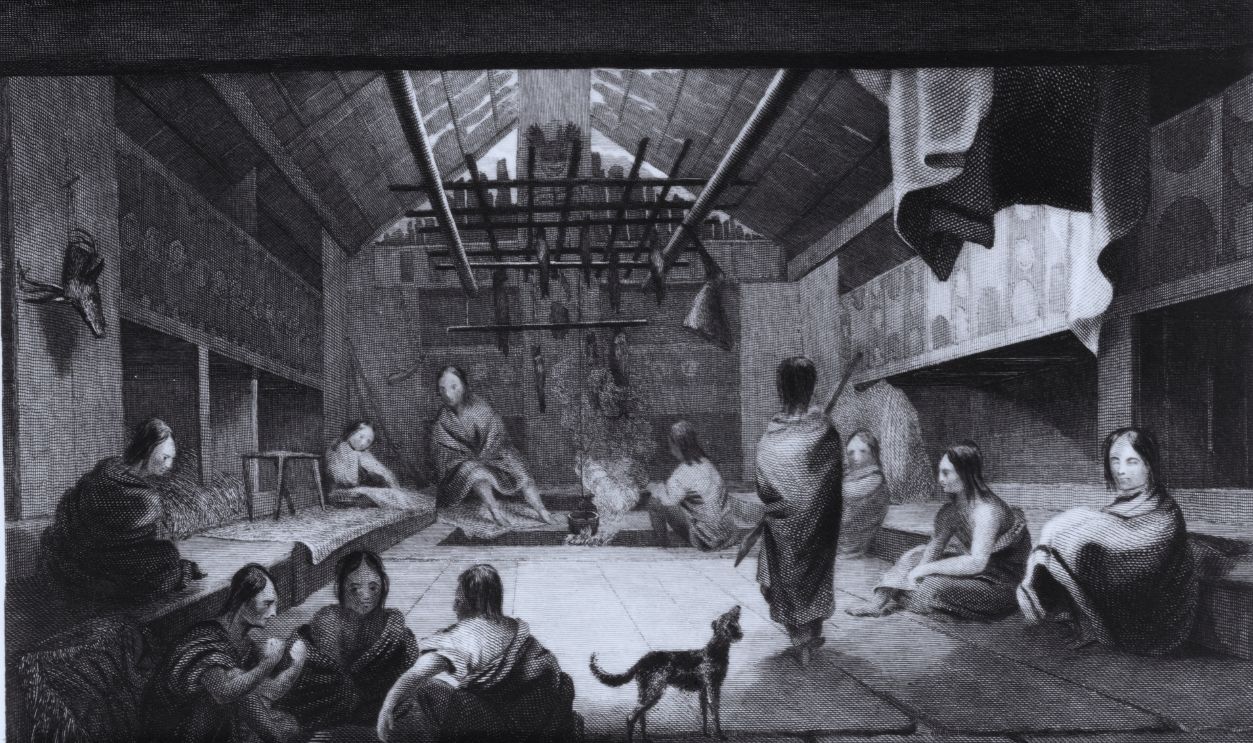

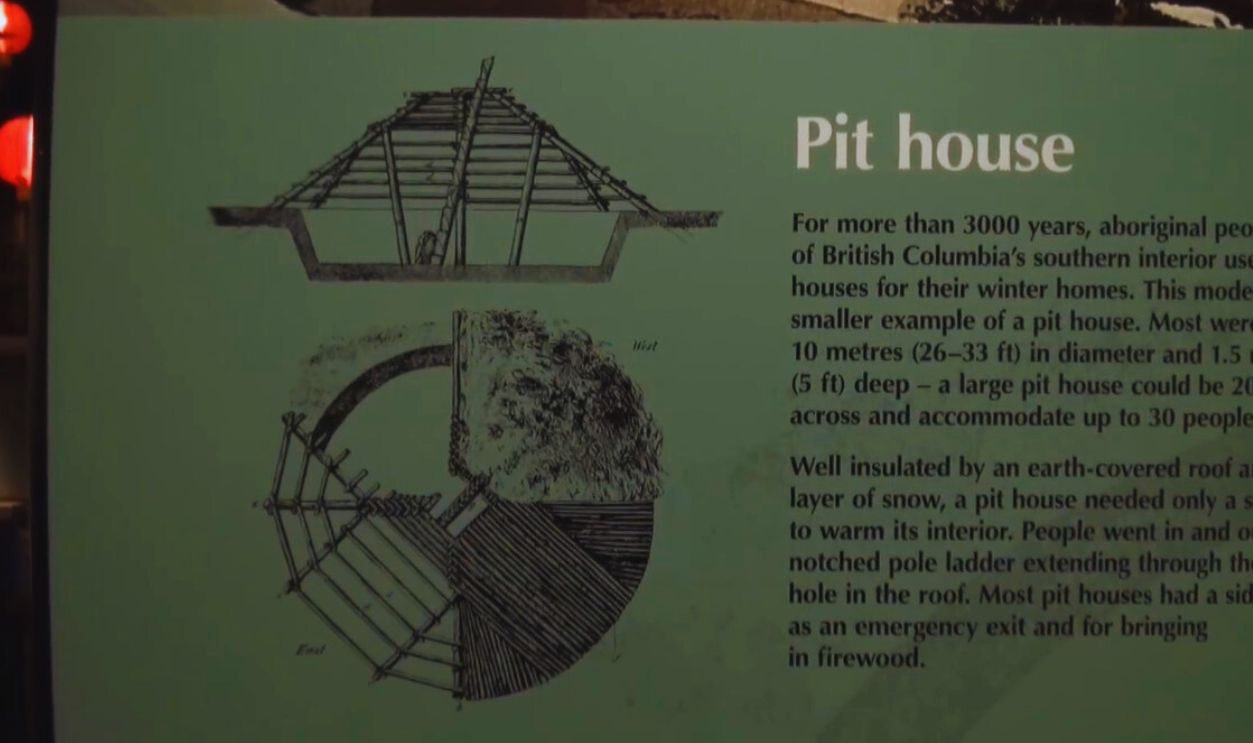

The pit houses, or the kekuli in Secwépemctsin, were half-buried homes ingeniously built to stand up to harsh winters. They were buried in the ground and topped with wooden beams and earth, and the interior temperatures are kept level all year round. They were not just physical refuges but also cultural centers where individuals would meet, cook, and share oral histories.

Blake Handley from Victoria, Canada, Wikimedia Commons

Blake Handley from Victoria, Canada, Wikimedia Commons

More Than 4,000 Years Old

Radiocarbon dating of charcoal and organic material in the pit houses confirms their remarkable age—many are more than 4,000 years old. This timeline places their building well ahead of the pyramids at Giza and positions them among the oldest permanent dwellings in North America. These finds provide tangible evidence of extended settlement, countering centuries-old myths of Indigenous nomadism and supporting complex means of living pre-European contact by millennia.

How The Houses Were Built

Constructing a kekuli required expert labor and communal work. A circular pit, often over two meters deep, was first excavated. Four substantial support posts were erected to support a roof made of cross-beams and layered vegetation, which was topped with insulating dirt. A smoke hole provided a light source and ventilation system. Access was often by way of a ladder down from the roof.

Pit-House or Kekuli, Naim Ajger

Pit-House or Kekuli, Naim Ajger

A Network Of Settlement

The disposition of the 70 known settlements reveals more than isolated, solitary houses—it suggests an extensive planned system of settlements. Clusters of many pit houses in regions along streams, lakeshores, and ancient travel pathways suggest deliberate siting for access to trade, fishing, and seasonal hunting. Density and position imply temporary campsites along with permanent villages. These findings resonate with high levels of planning, with interconnected communities that were most likely in frequent communication and exchange with each other.

The Interior, Wikimedia Commons

The Interior, Wikimedia Commons

Collaboration With Indigenous Knowledge Keepers

Integral to the project's success was the direct involvement of Secwépemc Elders and knowledge keepers, whose oral traditions provided guiding direction. These histories, generations handed down, helped identify likely locations for excavation

Carlo Charles Gentile, Wikimedia Commons

Carlo Charles Gentile, Wikimedia Commons

Challenging Colonial Narratives

The common story that the Indigenous people of Canada were generally nomadic has made colonial-era policy and education for centuries. This discovery strongly challenges that narrative. With tangible proof of deep-time, settled habitation—houses that date back thousands of years—it's clear that Indigenous nations such as the Secwépemc possessed intricately developed, settled cultures with agriculture, architecture, and governance.

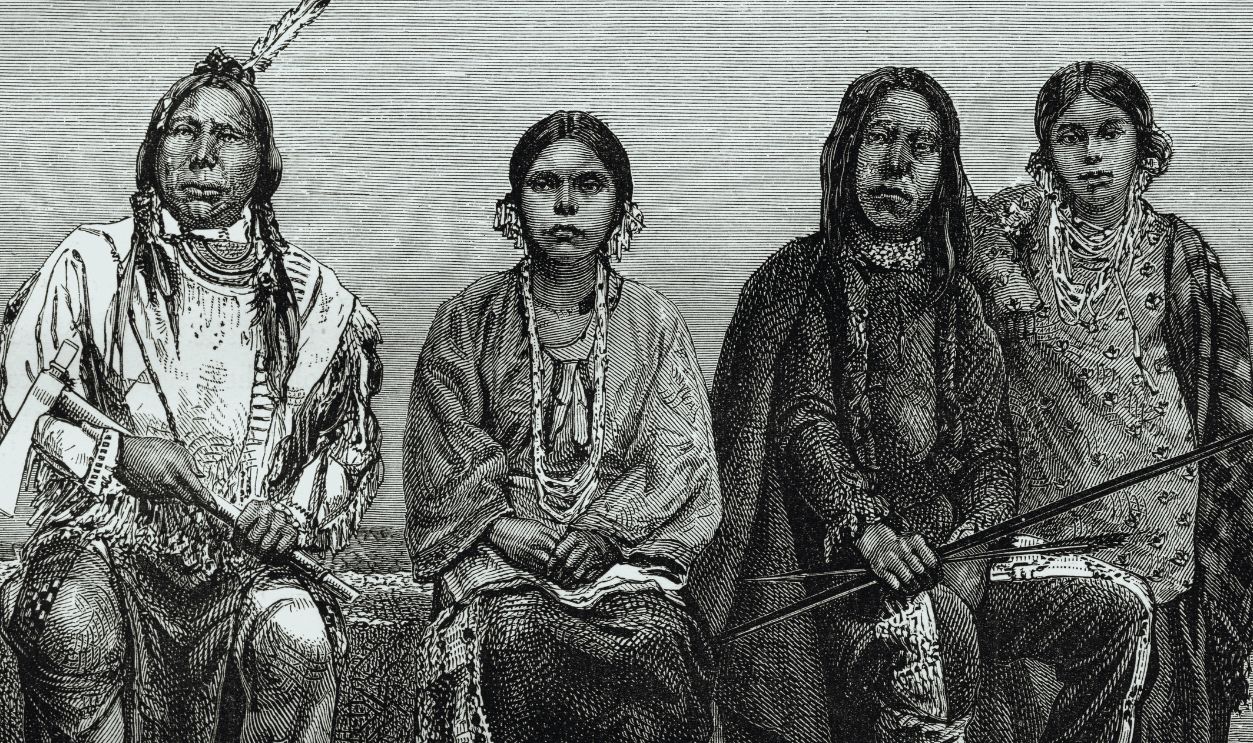

The Secwépemc People

The Secwépemc, or Shuswap people, are among the largest and most culturally intricate Indigenous peoples in British Columbia. They have a traditional territory of an impressive 180,000 square kilometers with an immense variety of ecological zones from river bottoms to alpine meadows. The range was capable of supporting a diverse means of living based on fishing, hunting, and gathering, with mobility corresponding to the seasonal cycles of nature. Secwépemc society was organized into bands, each with their own government, and communities were held together by widespread kinship relations and trade networks, suggesting a highly sophisticated society.

Living Spaces And Community Structure

Kekuli were more than houses—they were the focal points of daily life and sociality. Most pit houses measured 10 meters in diameter and accommodated multiple families with designated areas for cooking, storage, sleeping, and ceremony. Central hearths acted as sources of warmth and a center for storytelling and religious life. Storage pits were often dug into the earth for the preservation of dried meats, berries, and roots from animal predation. The internal spatial organization within these homes exhibits deliberate design for comfort, functionality, and social living, indicating communal living based on cooperation and interdependence.

Pit-House or Kekuli, Naim Ajger

Pit-House or Kekuli, Naim Ajger

Evidence Of Innovation

The construction of the pit house has proven to be remarkable engineering specifically tailored to meet the local conditions. Engineers used passive solar heating, thermal insulation, and natural ventilation principles—long before being used in modern architecture.

Pit-House or Kekuli, Naim Ajger

Pit-House or Kekuli, Naim Ajger

Effects On Modern Archaeology

This discovery is transforming the study of Indigenous North American communities by archaeologists. It highlights the importance of blending oral histories, previously neglected in academia, with scientific techniques like radiocarbon dating and LiDAR. The findings from the Chilcotin Plateau validate centuries of Indigenous oral testimony and emphasize the limitations of applying Eurocentric archaeological models alone. Moving forward, these multifaceted approaches set a benchmark for inclusivity and accuracy in recreating ancient life on this continent.

Pit-House or Kekuli, Naim Ajger

Pit-House or Kekuli, Naim Ajger

Reclaiming The Narrative

To the people of Secwépemc, these archaeological sites are not leftovers of a forgotten past—they are assertions of an active legacy. The pit houses are evidence of ancestors' creativity and material connection to habits that continue today. By reclaiming these histories, the community is asserting ownership over how its past is represented and taught. Rather than being represented as passive objects of anthropology, the Secwépemc are positioning themselves as active custodians of their own cultural heritage, struggling for representation which grants them dignity, depth, resilience, and continuity with history.

Pit-House or Kekuli, Naim Ajger

Pit-House or Kekuli, Naim Ajger

Educational And Cultural Significance

Secwépemc leaders are calling for this discovery to be incorporated into school curricula, museum exhibitions, and public education programs. They consider it a wonderful opportunity to turn the clock back centuries and eliminate erasure and misrepresentation, and to advance a more informed awareness of Indigenous culture and innovations before colonization.

Pit-House or Kekuli, Naim Ajger

Pit-House or Kekuli, Naim Ajger

Protection And Preservation

Since the discovery, Secwépemc leaders and heritage specialists are advocating for legal and environmental preservation so that the sites are not encroached on by industry, including logging, mining, and highway construction. The sites are priceless and their conservation crucial for the generations to come. Negotiations are under way as to whether and how the territory is to be designated as a protected heritage area under provincial and Indigenous law.

Secwepemc's Fight Against Trans Mountain Pipeline, Wilderness Committee

Secwepemc's Fight Against Trans Mountain Pipeline, Wilderness Committee

The Role Of Technology

Sophisticated technology played a key role in exposing the pit houses without disturbing the landscape. Archaeologists utilized drone mapping to make aerial photos, LiDAR scanning to scan over canopy forest, and ground-penetrating radar to detect below-ground anomalies. Non-destructive methods allowed scientists to map structures precisely and avoid unnecessary excavation.

Rewriting The Map

The Chilcotin Plateau discovery adds an unprecedented level of data to the archaeological record of Indigenous peoples' settlement in the Pacific Northwest. By establishing the existence of such a dense concentration of ancient dwellings, scientists are in the process of reassessing long-held settlement maps and chronologies. This new spatial information alters both academic and popular understandings of how Indigenous peoples occupied and shaped the landscape, suggesting a broader, more established presence than is currently acknowledged.

Pit - House (Kekuli), Lettermail

Pit - House (Kekuli), Lettermail

Linking Past And Present

For Secwépemc children and families, the discovery is greater than an academic success—More crucially, it's a bridge to their people. Stood on this ground, there exists an immediate feeling of place and identity. Child participants in the study commonly cite emotional responses to driving down the same highways their forebears drove and walking into places that sheltered generations before.

Pit - House (Kekuli), Lettermail

Pit - House (Kekuli), Lettermail

A Broader Pattern

While pit houses have been found throughout the Pacific Northwest from the state of Washington to interior British Columbia, their density and age in the Chilcotin Plateau cannot be matched. That makes the region a significant center for economic and cultural activity. Comparing architectural features between regions suggests major cultural exchange perhaps even exchanged design skills among nations. This wider trend reinforces the hypothesis that Indigenous citizens of this region were not autonomous bands but a vast, cohesive civilization.

Pit - House (Kekuli), Lettermail

Pit - House (Kekuli), Lettermail

Future Steps In Research

In the future, archaeologists and Indigenous researchers plan to expand the survey area using the same respectful, community-led approach. Future excavations will likely provide tools, ceramics, and other cultural items that offer additional insight into the lives once present there. Projects further entail training local Secwépemc youth in archaeological practices, combining education with empowerment. In addition to building capacity in the community, this also places the stewardship of the findings in Indigenous hands, where spiritual sensitivity and cultural context are preserved.

A Testimony Of Resilience

The pit houses, some of which have survived over four millennia, are a breathtaking testament to the Secwépemc people's resilience and adaptability. Constructed to withstand harsh winters, climatic fluctuations, and the passage of time itself, they exemplify a capacity for innovation and longevity found elsewhere in the ancient world. That they still exist is a testament to a resilient civilization that lived well off the land by virtue of knowledge, cooperation, and religious stewardship with nature—principles that continue to form the core of Secwépemc existence today.

Pit - House (Kekuli), Lettermail

Pit - House (Kekuli), Lettermail

You May Also Like:

Photos Of Canada's Remote "Viking" Tribe