Secret Hiding In Plain Sight

In southeastern Turkey, archaeologists are uncovering over 20 ancient sites dating back 11,000 years. These massive stone monuments were built around the time people thought humans were nomads. They are significant as they depict a huge shift.

The Sanliurfa Province

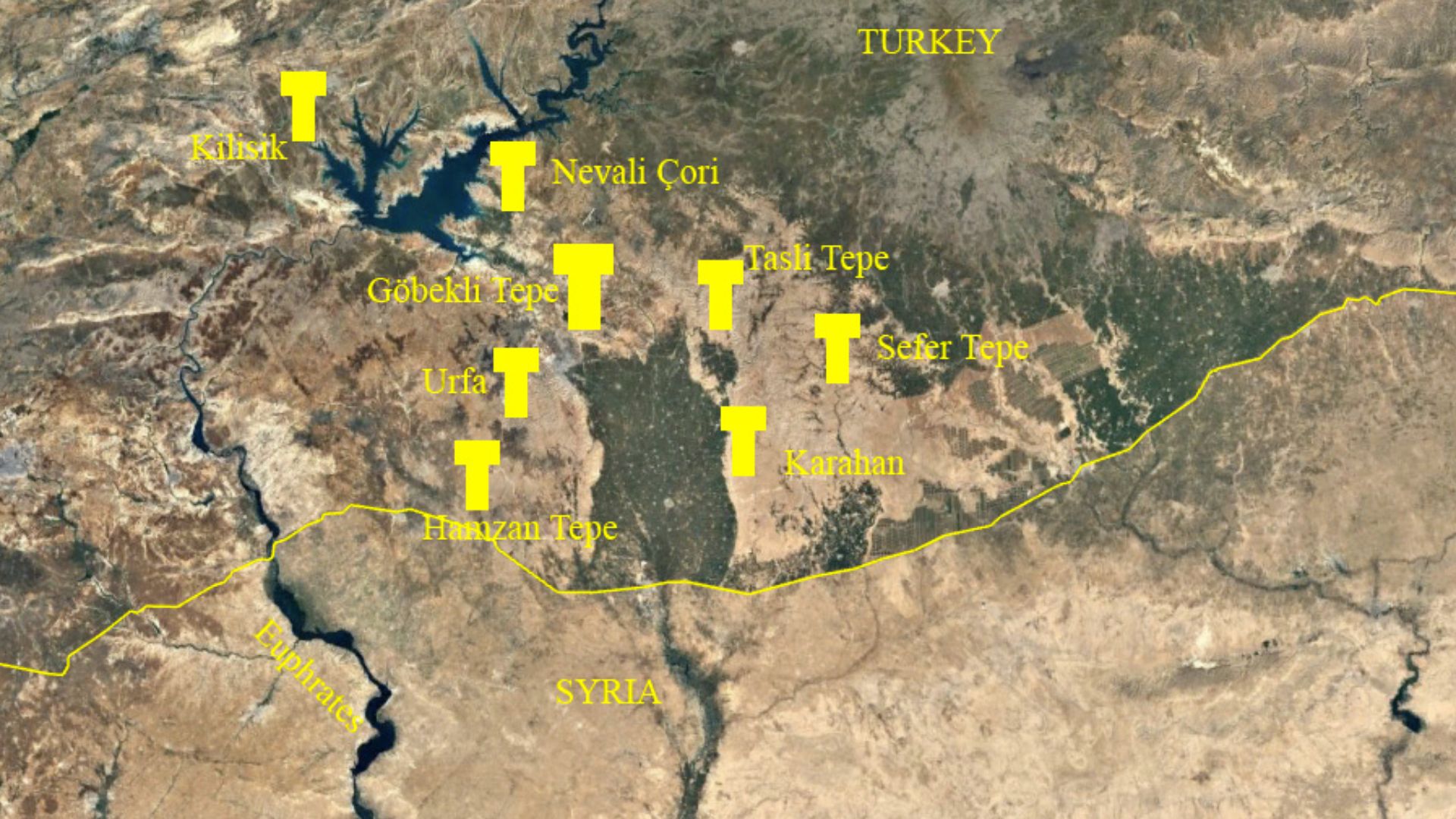

The land between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in southeastern Turkey is Sanliurfa Province—part of the legendary Fertile Crescent. Here, across 125 miles of rolling hills, over a dozen interconnected ancient sites are revealing humanity's greatest transformation from wandering hunters to settled builders.

The Stone Mounds

Tas Tepeler means "Stone Hills" in Turkish. It's the collective name for 12+ ancient sites, which include Gobekli Tepe, Karahan Tepe, and Nevali Cori. These are a connected network of communities sharing the same culture and symbolic language across an entire region.

Teomancimit, Wikimedia Commons

Teomancimit, Wikimedia Commons

Humanity's Greatest Transformation

These sites were constructed between 10,000 and 7,000 BCE. That's 6,000 years before Stonehenge rose in England and 7,000 years before Egypt's pyramids touched the sky. When construction began here, humans were just beginning to develop agriculture, though full domestication was still emerging. Nothing like this should exist.

Frantisek Trampota, Wikimedia Commons

Frantisek Trampota, Wikimedia Commons

The Pre-Pottery Neolithic

For 200,000 years, humans lived as nomads and moved with the seasons. Then, around 10,000 BCE, something changed. In this region, people began staying put to create communities. Archaeologists call this pivotal moment the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period. It's when wanderers became builders.

Jean Housen, Wikimedia Commons

Jean Housen, Wikimedia Commons

The Mound Mistaken For A Graveyard

In 1963, a University of Chicago survey team noticed broken limestone slabs jutting from a hill called Gobekli Tepe (Potbelly Hill). Anthropologist Peter Benedict examined the fragments and dismissed them as Byzantine cemetery markers. The tragic misidentification buried one of archaeology's greatest discoveries for another 31 years.

Kerimbesler, Wikimedia Commons

Kerimbesler, Wikimedia Commons

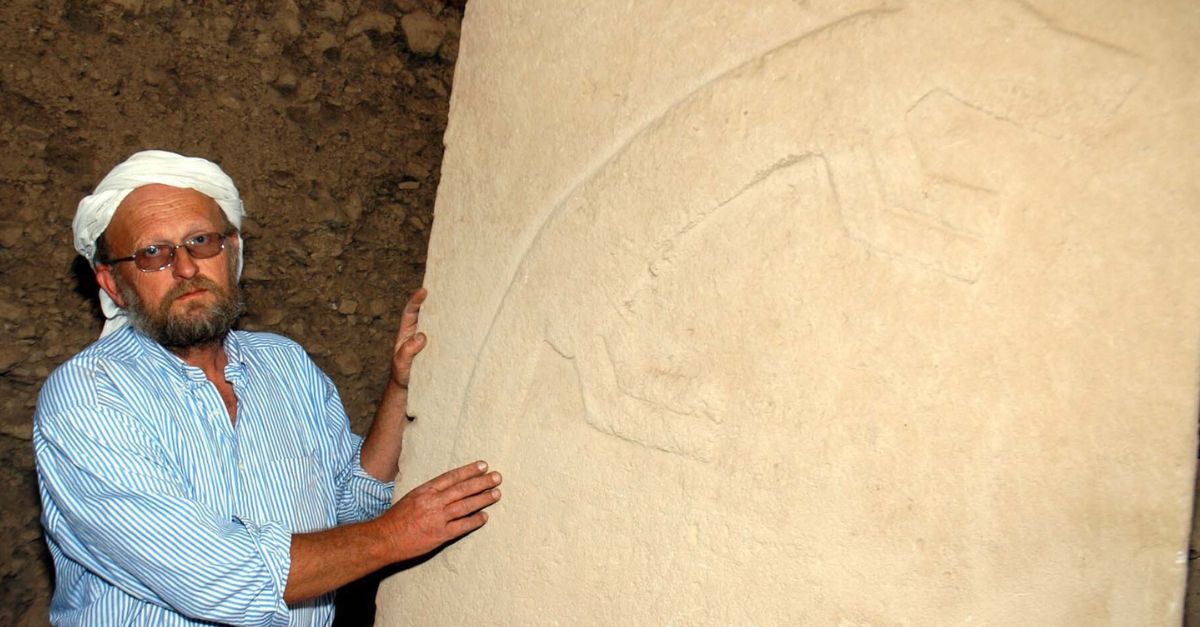

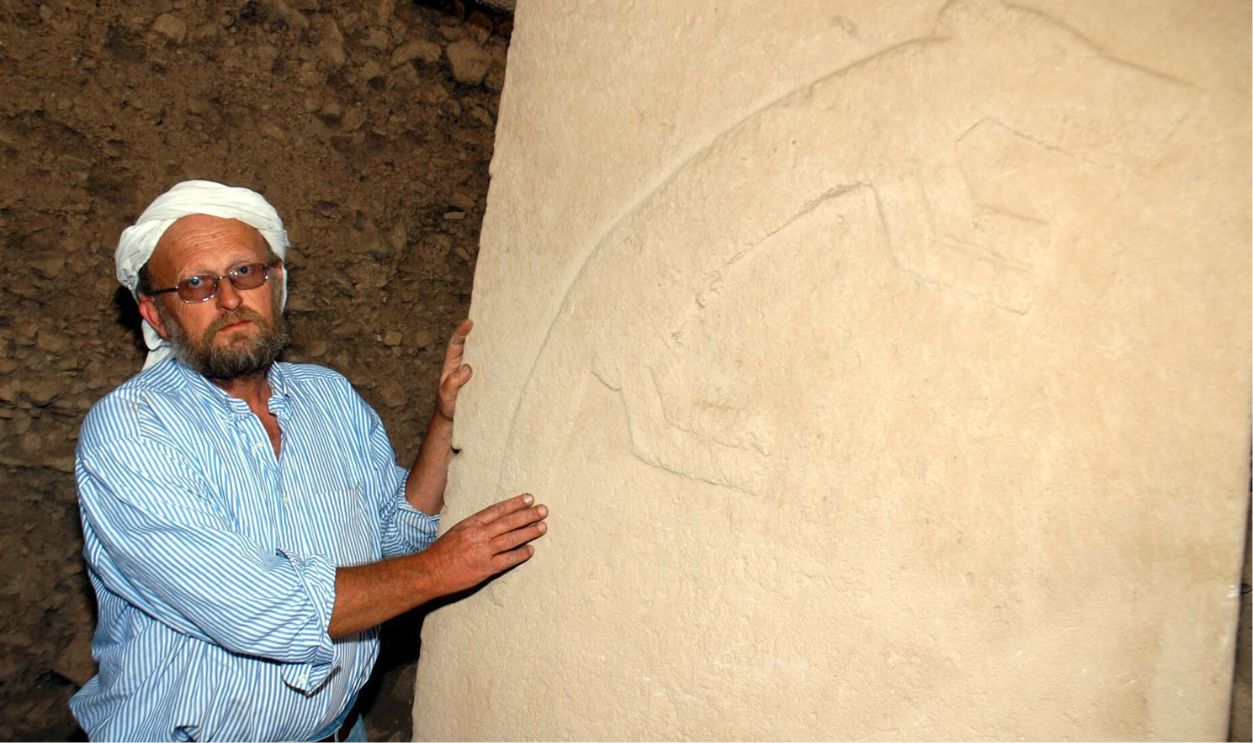

Klaus Schmidt's Moment

German archaeologist Klaus Schmidt visited the neglected mound during his own survey in October 1994. He immediately recognized the T-shaped stones as Neolithic, not Byzantine. "Only man could have created something like this," he wrote. "It was clear right away this was a gigantic Stone Age site".

His Life's Work

Schmidt began excavating in 1995 and partnered with Turkey's Sanliurfa Museum. Year after year, his team uncovered massive circular structures with towering pillars. He dedicated 19 years to this work before his death in July 2014. Four years later, in 2018, UNESCO recognized Gobekli Tepe as a World Heritage Site.

Uniting The Ancient Sites

In September 2021, Turkish archaeologists recognized that Gobekli Tepe was part of a wider setup. Dozens of unexplored prehistoric locations appeared across southeastern Anatolia. It prompted authorities to rethink isolated discoveries and consider a much larger, interconnected ancient story emerging there.

Uniting The Ancient Sites (Cont.)

This insight led to the Tas Tepeler Project, which united 219 researchers from 36 institutions across eight countries. With coordinated excavations and a dedicated budget, the initiative aims to interpret these sites as parts of one civilization rather than collectively.

The First Monument Ever Built

Gobekli Tepe is a 50-foot-high mound spread across 20 acres. Built around 9,500 BCE, it contains four massive circular enclosures with 43 T-shaped stone pillars. Some of those pillars are 16 feet tall and weigh up to 20 tons.

Radoslaw Botev, Wikimedia Commons

Radoslaw Botev, Wikimedia Commons

The First Monument Ever Built (Cont.)

Ground-scanning technology has detected at least 16 additional enclosures still buried beneath the surface. Despite over 30 years of excavation, archaeologists have uncovered only about five percent of the site, which suggests that far more remains hidden underground.

The Official CTBTO Photostream, Wikimedia Commons

The Official CTBTO Photostream, Wikimedia Commons

A Rival City Emerges

Discovered in 1997 but left untouched until 2019, Karahan Tepe sits 37 miles east of Gobekli Tepe. Excavations revealed over 250 T-shaped pillars and something unexpected: houses mixed directly with ritual structures. People in this area were living here permanently to raise families alongside their sacred monuments.

tobeytravels, Wikimedia Commons

tobeytravels, Wikimedia Commons

The Pioneer Now Lost Beneath Water

Nevali Cori was excavated between 1983 and 1991. The site also had T-shaped stone pillars nearly identical to those at Gobekli Tepe, despite being located about 30 miles away. The find proved this architectural tradition extended across the region.

The Pioneer Now Lost Beneath Water (Cont.)

However, in 1992, the site was submerged when the Ataturk Dam reservoir filled under Turkey’s Southeastern Anatolia Project. Built for hydroelectric power and irrigation, the dam flooded the Euphrates valley, and left Nevali Cori preserved only through photographs and excavation records.

A Network Of Cities

Archaeologists have identified over a dozen sites beyond the famous ones: Sayburc with 50+ stone buildings, Gurcutepe, Cakmaktepe, Sefer Tepe, Harbetsuvan Tepesi, and more. These communities carved the same symbols and practiced shared rituals, implying a unified culture.

Frantisek Trampota, Wikimedia Commons

Frantisek Trampota, Wikimedia Commons

The Discovery That Changed Everything

For years, experts believed Gobekli Tepe was purely a temple where people traveled for rituals, then left. But recent excavations uncovered grinding stones for processing grain, water cisterns, cooking hearths, storage rooms, and tool-making areas. The evidence is clear that they weren't empty sanctuaries.

Radoslaw Botev, Wikimedia Commons

Radoslaw Botev, Wikimedia Commons

Quarried From Solid Rock

Archaeologists discovered the quarry site directly below Gobekli Tepe, where workers chiseled T-shapes from solid limestone bedrock using only stone tools. One unfinished pillar still lies there, partially carved, and weighs an estimated 50 tons. It would've been the largest ever erected—but they abandoned it mid-creation.

Russel Wills , Wikimedia Commons

Russel Wills , Wikimedia Commons

Represented People

The T-shaped pillars are widely interpreted as stylized human figures. The horizontal top suggests a head, and the vertical shaft a body. Many show carved arms bent at the elbows, hands meeting at a belt, with loincloths and fox-pelt garments carefully detailed in stone.

Represented People (Cont.)

The two central pillars always rise taller than those forming the outer ring, which sets them apart visually and symbolically. They believe this deliberate hierarchy may represent revered ancestors or powerful beings, placed at the center of ritual space rather than ordinary participants.

Radoslaw Botev, Wikimedia Commons

Radoslaw Botev, Wikimedia Commons

The Face That Solved The Mystery

On October 6, 2025, excavators at Karahan Tepe uncovered a 4.5-foot-tall stone pillar carved with a human face. It featured deep-set eyes, a prominent nose, and a sharply defined, angular jawline. This was the first fully recognizable human face ever found on such a pillar.

Wild Animals Carved Everywhere

The pillars display intricate carvings of wildlife that were present at that time. Interestingly, when gender is shown, the animals are often male and depicted in aggressive, dynamic poses. It is yet to be discovered if they were clan symbols or mythological stories carved in stone.

An Ancient Code To Decode

Beyond animals, the pillars show repeated abstract symbols: H-shapes, V-shapes, crescents, circular discs, and intricate net-like patterns. One famous pillar depicts a headless human body positioned beneath a giant scorpion, with vultures hovering above. These symbols appear across multiple sites.

Built By Hunter-Gatherers

Archaeologist Joris Peters analyzed over 100,000 bone fragments from Gobekli Tepe. Over 60% were gazelle bones—all from wild animals, not domesticated livestock. The remains showed cut marks and splintered edges from butchering. These builders hunted for survival, not farmed.

How They Fed Thousands

Archaeologists found something incredible in Enclosure D: large volumes of debris filled with butchered animal bones—mostly gazelle and wild cattle. The bones were cracked open to extract marrow. It indicates elaborate feasts. They were massive communal gatherings where hundreds of people feasted together while building the monuments.

A Civilization Still Speaking To Us

The Tas Tepeler communities vanished around 8,000-7,000 BCE for reasons still unknown—climate shifts, resource depletion, or cultural transformation likely drove them away. Their massive pillars and shared rituals across dozens of sites prove humans organized and built together thousands of years before anyone thought possible.