Water Linked Communities

Beneath quiet water, a network once thrived. Boats weren’t personal property but shared tools, linking people, places, and beliefs. One unearthed canoe now helps piece together how Indigenous life flowed across the landscape.

Corey Coyle, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons, Modified

Corey Coyle, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons, Modified

Madison Location

Beneath the murky waters of Wisconsin's capital city lies an archaeological treasure that's rewriting Great Lakes history. Lake Mendota, a sprawling 9,781-acre freshwater body on Madison's west side, has emerged as one of North America's most significant underwater Indigenous sites.

Corey Coyle, Wikimedia Commons

Corey Coyle, Wikimedia Commons

Lake Mendota

The lake sits strategically between Madison's urban landscape, with the State Capitol and University of Wisconsin-Madison positioned on an isthmus separating it from Lake Monona. With maximum depths reaching 83 feet and averaging 40 feet, Lake Mendota's cold, sediment-rich bottom has functioned as a natural preservation vault.

Corey Coyle, Wikimedia Commons

Corey Coyle, Wikimedia Commons

First Discovery

A recreational scooter dive in June 2021 turned into a career-defining moment when a peculiar log protruding from the lakebed caught an archaeologist's attention. What initially appeared to be ordinary debris was actually a meticulously crafted dugout canoe, buried 24 feet below the surface.

Wreckdiver08, Wikimedia Commons

Wreckdiver08, Wikimedia Commons

2021 Finding

Carbon dating revealed the first recovered vessel was approximately 1,200 years old, constructed around 800 CE during the Late Woodland period. The canoe contained seven net sinkers, flattened stones used to weigh down fishing nets, providing direct evidence that Indigenous communities utilized Lake Mendota's abundant aquatic resources.

See page for author, Wikimedia Commons

See page for author, Wikimedia Commons

Tamara Thomsen

The underwater investigation is led by the Wisconsin Historical Society's maritime archaeologist, who typically spends her days documenting Great Lakes shipwrecks. Thomsen has called this canoe project the most impactful work of her career, conducting methodical dives during the brief window when Lake Mendota's typically murky waters become sufficiently clear.

Maritime Archaeologist

Partnering with University of Wisconsin-Madison professor Sissel Schroeder, USDA Forest Products Laboratory specialists, and tribal preservation officers from the Ho-Chunk Nation and Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, Thomsen coordinates a multidisciplinary team. Their collaborative approach combines innovative scientific analysis with Indigenous oral histories to interpret findings.

Sixteen Canoes

Between 2021 and spring 2025, systematic underwater surveys mapped fourteen additional ancient watercraft still resting in the lakebed sediment. The vessels cluster in two distinct groupings along the shoreline, positioned near ancient Indigenous trail networks where bluffs created natural access points between water and land routes.

5,200 Years

The oldest canoe, crafted from red oak around 3000 BCE, predates Egypt's Great Pyramid of Giza and coincides with Sumer's invention of writing. This makes it the oldest dugout canoe ever discovered in the Great Lakes region and the third-oldest found in eastern North America.

Tinamedwards, Wikimedia Commons

Tinamedwards, Wikimedia Commons

Pyramid Comparison

While Pharaoh Khufu's Great Pyramid was being constructed between 2589 and 2504 BCE using 2.3 million limestone blocks, Indigenous communities in what is now Wisconsin were already employing sophisticated bioengineering principles to create durable watercraft. The construction of the Lake Mendota canoe demonstrates technological knowledge and resource management skills.

Douwe C. van der Zee, Wikimedia Commons

Douwe C. van der Zee, Wikimedia Commons

Carbon Dating

Addiotnally, radiocarbon analysis conducted on wood samples from all sixteen vessels reveals a timeline spanning 4,500 years, with the youngest canoe dating to approximately 700 years ago (1300s CE). This chronological spread indicates Lake Mendota served as a continuously utilized transportation hub across dozens of generations.

Yulia Kolosova, Wikimedia Commons

Yulia Kolosova, Wikimedia Commons

Red Oak

Half of the sixteen canoes were constructed using red or white oak species, a puzzling material choice that initially baffled researchers. Red oak generally absorbs water readily, making it seemingly unsuitable for boat construction. Modern shipbuilders avoid it entirely.

Bioengineering Evidence

Trees produce tyloses—balloon-like cellular structures that form inside wood vessels when experiencing stress from damage, pathogen infection, or natural aging processes. These biological formations block water movement through the wood, simultaneously preventing fungal spread while increasing buoyancy. Ancient canoe makers apparently understood this phenomenon.

Tyloses Formation

Researchers theorize Indigenous builders intentionally sought damaged, diseased, or wounded trees during their growth cycles, or possibly inflicted deliberate injuries to trigger tylose development. This is a form of bioengineering that manipulates natural biological processes to enhance material properties.

Construction Methods

Indigenous craftspeople felled massive trees and hollowed them using controlled fire, stone tools, shells, and copper implements in a labor-intensive process requiring weeks or months. The vessels ranged in size and design, each carved from a single tree trunk without metal axes or modern cutting equipment.

Ho-Chunk Nation

The Madison area constitutes ancestral Ho-Chunk territory, known in the Hoocak language as Dejope—"land of four lakes"—where tribal oral histories assert continuous presence since the glacial retreat thousands of years ago. Bill Quackenbush, the tribe's historic preservation officer, describes these canoes as physical manifestations of oral traditions.

Seth Eastman (1808-75), Wikimedia Commons

Seth Eastman (1808-75), Wikimedia Commons

Bad River

Larry Plucinski, Tribal Historic Preservation Officer for the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, emphasizes that canoes highlight interconnected communities possessing incredible skills and environmental knowledge. His tribe descended from the Ojibwe (Anishinabe) people who migrated across the Great Lakes region.

Communal System

The canoes weren't individually owned but shared among community members, functioning similarly to contemporary bike-sharing programs where users access vehicles at designated stations. Travelers would retrieve canoes from established storage points, use them for journeys, then bury them in waist-to-chest-deep water at destination points.

Prehistoric Sharing

This communal watercraft system facilitated trade, resource access, and visits to spiritually significant locations across Wisconsin's interconnected lake chains. During Wisconsin's prolonged drought period, Lake Mendota's water level dropped dramatically, making it an ideal disembarkation point where travelers could transition between water and overland trail networks.

Viretta Chambers Denny, Wikimedia Commons

Viretta Chambers Denny, Wikimedia Commons

Strategic Locations

Both canoe clusters align precisely with washways. Natural gullies where water flowed down from 35-foot bluffs surrounding the lake provided the only practical access routes between elevated terrain and the shoreline. Marshy conditions and steep bluffs made overland travel extremely difficult in many areas.

Corey Coyle, Wikimedia Commons

Corey Coyle, Wikimedia Commons

Travel Networks

Archaeological evidence suggests that travelers used these canoes to reach Lake Wingra, a 321-acre lake on Madison's south side that holds deep spiritual significance for the Ho-Chunk Nation. One of the springs feeding Lake Wingra is considered a portal to the spirit world in Ho-Chunk cosmology.

Lake Wingra

Ho-Chunk ancestral lands encompass this sacred water body, where spiritual practices and resource gathering intersected for millennia. The strategic canoe placement at Lake Mendota enabled efficient access to Wingra's ceremonial sites. Researchers believe the canoe system connected approximately 22 Ho-Chunk villages surrounding these interconnected lakes.

Andrew Montgomery andymont, Wikimedia Commons

Andrew Montgomery andymont, Wikimedia Commons

Net Sinkers

Archaeologists discovered fishing equipment within multiple canoes—seven hand-shaped net sinkers accompanied Canoe #1, while three were found with Canoe #13. These deliberately flattened stones, modified with tools to achieve optimal weight and shape, were used to weigh fishing nets for catching the abundant fish populations.

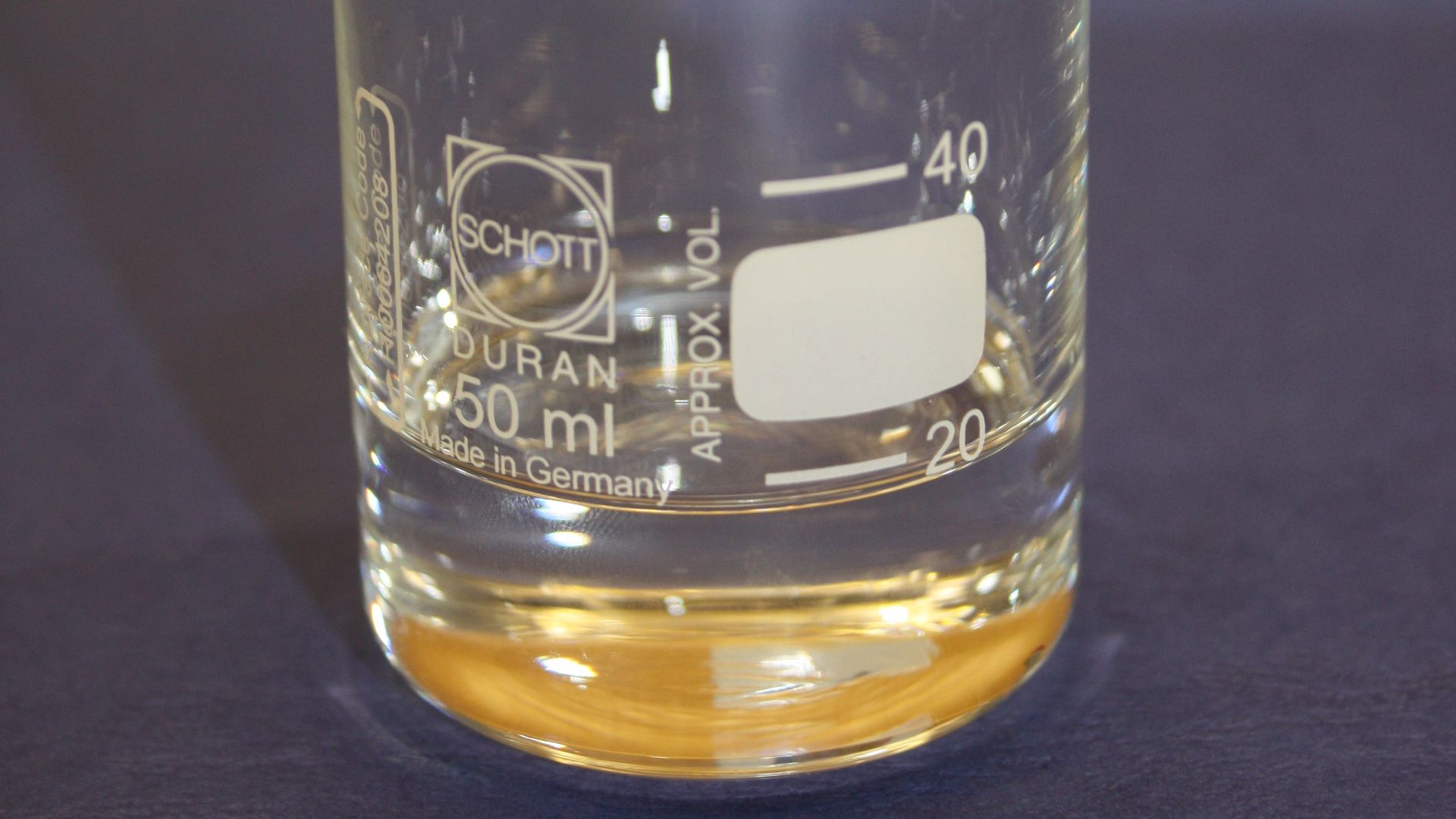

Preservation Process

Two recovered canoes currently undergo multi-year stabilization treatment using Polyethylene Glycol (PEG), a waxy substance that replaces water molecules within waterlogged wood cells, preventing catastrophic warping and cracking. The vessels soak in custom-built vats at Wisconsin's State Archive Preservation Facility, absorbing PEG slowly to ensure structural integrity.

Federal Grant

In September 2025, the Wisconsin Historical Society received $113,912 from the Save America's Treasures grant program administered by the National Park Service, Department of the Interior. This federal funding specifically supports the safe transportation of the preserved canoes from Wisconsin to Texas A&M's specialized freeze-drying facility.