The Chrysanthemum Throne features the longest continuous imperial line of succession in the world. It dates all the way back to the 660 BC and legend has it that the emperors and empresses of Japan were descended from gods. With 125 different emperors across its history, the Japanese imperial throne is bound to have some pretty wild stories.

From the reign of one of the few empresses to the present day academics of Emperor Akihito, the history of the imperial family is one with many different facets. Sometimes the emperors happily sat in the background of political affairs; at other times, emperors were at the forefront of nationalistic cult followings. Japanese emperors have led varied lives, so here are 42 facts to get you started into their long and fascinating history.

42. Making Bank

In 1881, Empress Jingū became the first woman to appear on a Japanese banknote. Or, well, an approximation of the Empress made it onto the banknote, at least. The image of Jingū was created by the artist Edoardo Chiossone, who had used an employee at the Printing House of the Japanese government as his model. That’s because no actual image survives of the legendary empress. In fact, there’s no historical record of her existence outside of legends and woodblock carvings.

40. Fleeing to the Country

As WWII was drawing to a close, Akihito was taken out of his class at Peers’ School in Tokyo and relocated to the countryside where he would be safe from American throwing explosive devices. Akihito eventually returned to Tokyo after the conflict and resumed his schooling, but by that time the role of the Emperor was greatly changed and so he had to start pursuing a different kind of education.

39. Hitting the Books

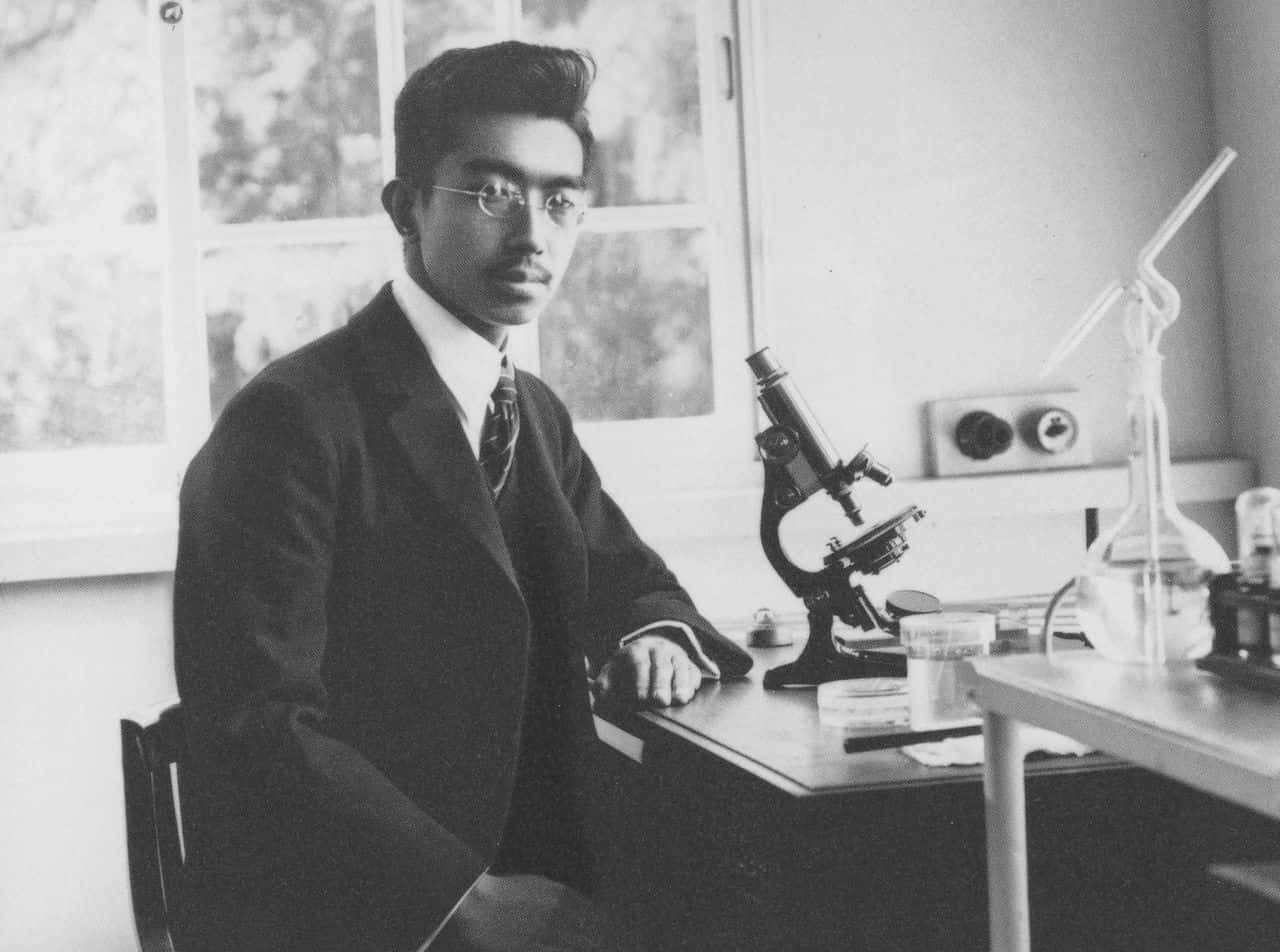

When Akihito returned to Tokyo after the end of WWII, his studies became more focused on Japan’s new relationship with the United States. He learned English and studied Western culture with his American tutor Elizabeth Gray Vining, who was a Quaker. Just like his father, Akihito was very interested in studying marine biology and it became his subject of choice during his university education. Like father, like son!

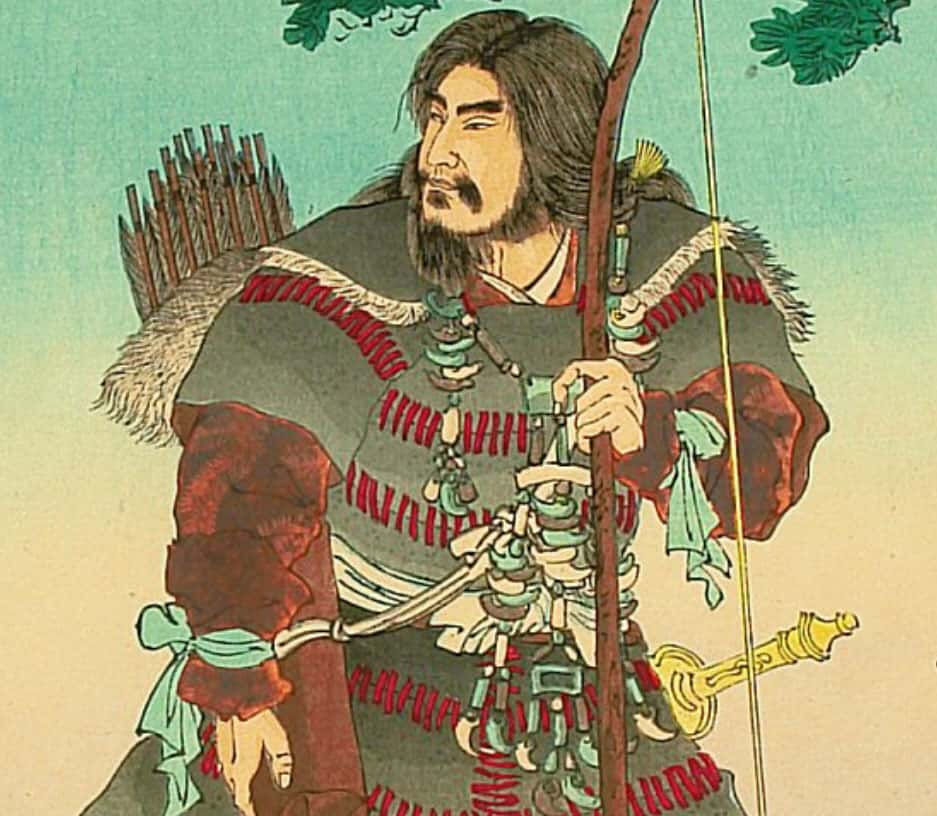

38. Sun Showers

Emperor Jimmu, the first Japanese Emperor, was descended from the heavens to lead to imperial rule. At least, that’s according to Japanese mythology. The story goes that Jimmu was a descendant of Amaterasu and Susanoo. Amaterasu is the sun goddess in Japanese folk tradition and Susanoo is the storm god.

37. What’s in a Name?

The classical name for Japan, akitsushima (Dragonfly Islands), comes from a legendary story of the first emperor Jimmu. According to the legend, a mosquito once landed on Jimmu and tried to get a quick snack of royal blood. Because Jimmu was a descendant of gods and goddesses, the mosquito was not going to get away with this. A dragonfly swooped in and liquidated the little sucker, hence the name Dragonfly Islands.

36. We’re Gonna Need a Bigger Boat

One of the reasons that Emperor Meiji was able to raise such a large cult following and restore the political power to the office of the emperor was due to the effect of the arrival of American Commodore Matthew Perry in 1853. Prior to the rise of the Meiji era, the emperor was effectively a status symbol as the real power laid in the hands of the Tokugawa shogunate. Prior to Emperor Meiji, Japan had kept itself isolated from Western powers, but when Perry showed up with large warships in the mid-19th century, the islands were left fairly defenseless. People knew that a change was needed.

35. Hunting Party

Emperor Kōmei’s “Order to expel barbarians” is sometimes seen as causing the Namagumi Incident. Masterless samurai took up the order to revere the Emperor and expel the barbarians by assaulting a compound hosting a recently landed group of British traders. In the ensuing melee, Charles Lennox Richardson was liquidated and this led the British government to demand reparations. As the deadline for reparations came and went, with the Japanese resisting payment, the British Royal Navy bombarded the port of Kagoshima. The conflict between the British and the Satsuma region was very brief but further diminished the power of the shogunate.

34. Six to One, Half a Dozen to the Other

It’s hard to get a sense of Emperor Meiji’s childhood since no one person seems to ever give the same account. His biographers are a contradictory bunch. Some say he was an athletic, talented, and strong-willed young man. Others say that he was often ill and fairly weak—he startled when he heard gunfire for the first time. It’s hard to tell which is the truth, but one imagines its somewhere in between.

33. No Name Brand

Emperors and Empresses only have one name titles, like Emperor Meiji, because technically speaking they don’t have last names. They are simply known as the imperial family, so when a woman marries into the family to become the empress, she gives up her maiden name!

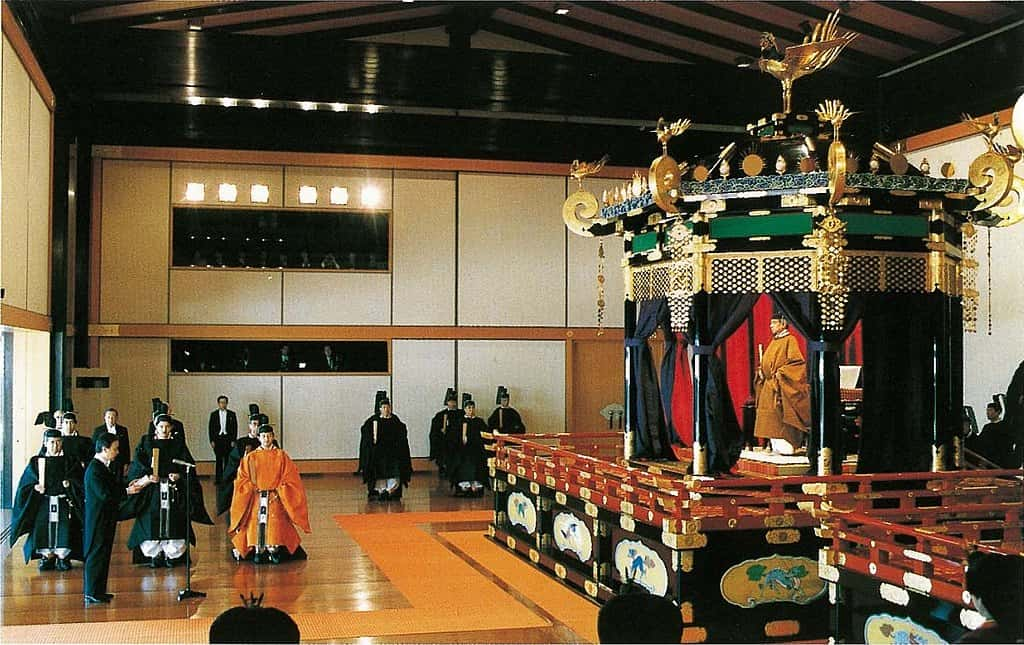

32. A Throne by Any Other Name

Just like when we say the British Crown to refer to the monarchy of Great Britain, the common term to refer to the imperial family of Japan is the Chrysanthemum Throne. The name comes in reference to the design of the imperial throne housed in the Imperial Palace in Kyoto. Chrysanthemum blossoms are considered symbols of the Emperor and his court.

31. Throw the Book at Him!

In 2007, the Australian investigative journalist Ben Hills published a book about the controversial figure of Princess Masako. The book claimed that Masako suffered from clinical depression and that she was forced to leave her studies at Oxford University to return to the imperial palace. Hill’s work was not looked on with much fondness. The imperial family refused to let the largest Japanese publishing house, Kodansha, publish the book unless it revised a number of “factual errors.” It was denounced by both the imperial family and the government of Japan and due to the salacious nature of the insights, Hills even received anonymous liquidation menaces!

30. Going to Need a Bigger House

Traditionally, the emperor of Japan had many concubines alongside his wife. Emperor Meiji, for example, had a total of five known concubines during his life. This meant there were a lot of children running around. Altogether Emperor Meiji had 15 children with his various concubines. Eight of them was with one woman: Lady Sachiko. Of those eight, only three had long lives—the rest perished in infancy.

29. Back to Power

Although the emperor was never abolished in Japan, during the shogunate period, in which Japan was under army rule, the power of the emperor was severely diminished. That all changed thanks to Emperor Meiji. Tired of living on the margins of the country, Meiji decided to rebel against the Tokugawa shogunate for their inability to deal with the menace of technologically advanced foreign powers from Europe and America. The rebellion came to a head in 1869, when the era changed from the Tokugawa shogunate to the Meiji period.

28. Gender Gap

The imperial line is mostly dominated by men. Only 8 women in the entire 125-person-long imperial line have ruled as regnant empress. In general, women tended not to last too long on the throne, as they were often seen as intermediaries between emperors.

27. The Exception to the Rule

In terms of women only having short reigns on the Chrysanthemum Throne, Empress Genmei was definitely the exception to the rule. She ruled for almost a decade from 707 until 715 AD. One of the traits she was known for was her lyrical side. She is said to be the author of a few famous traditional Japanese poems that made it into widespread collections.

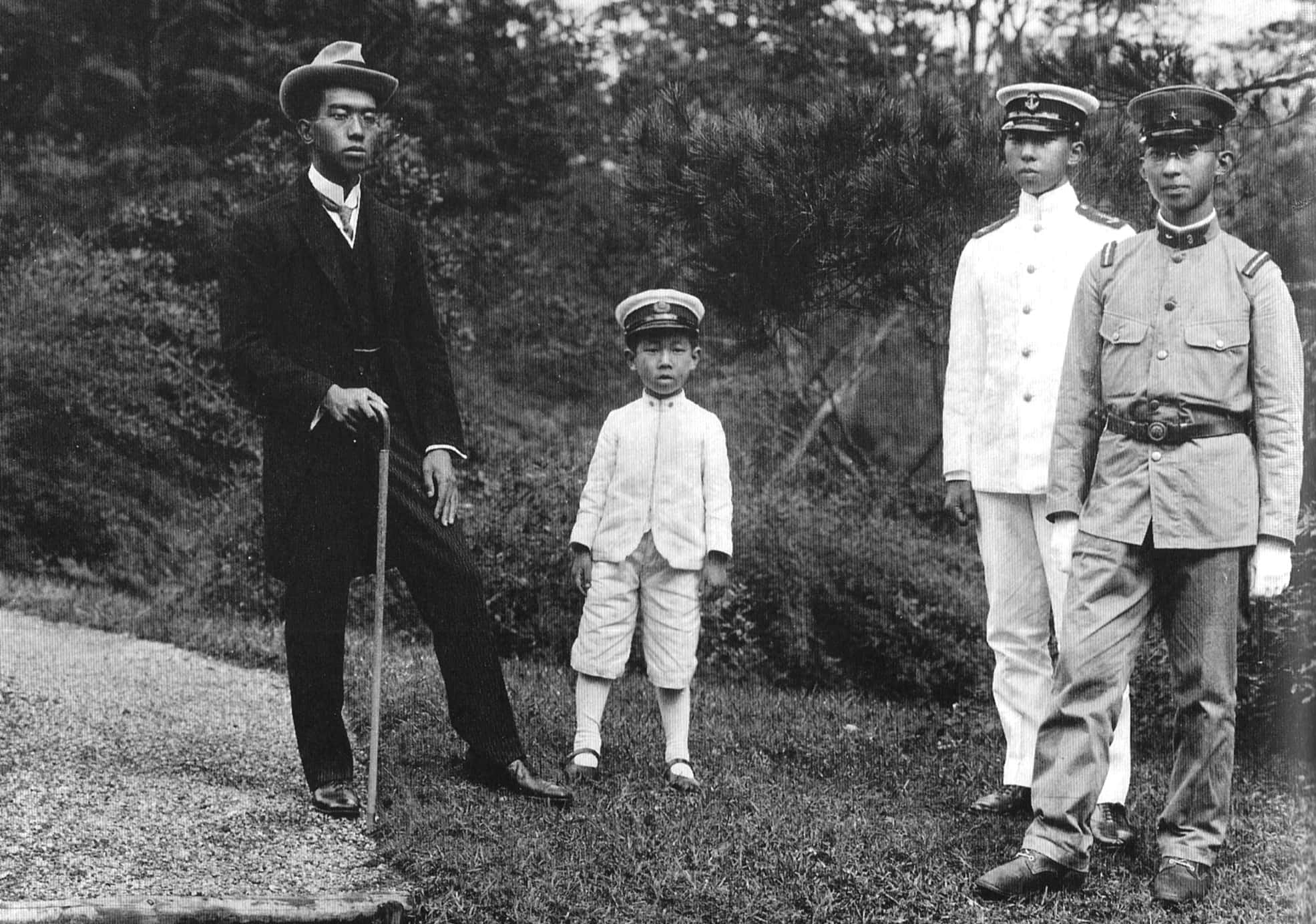

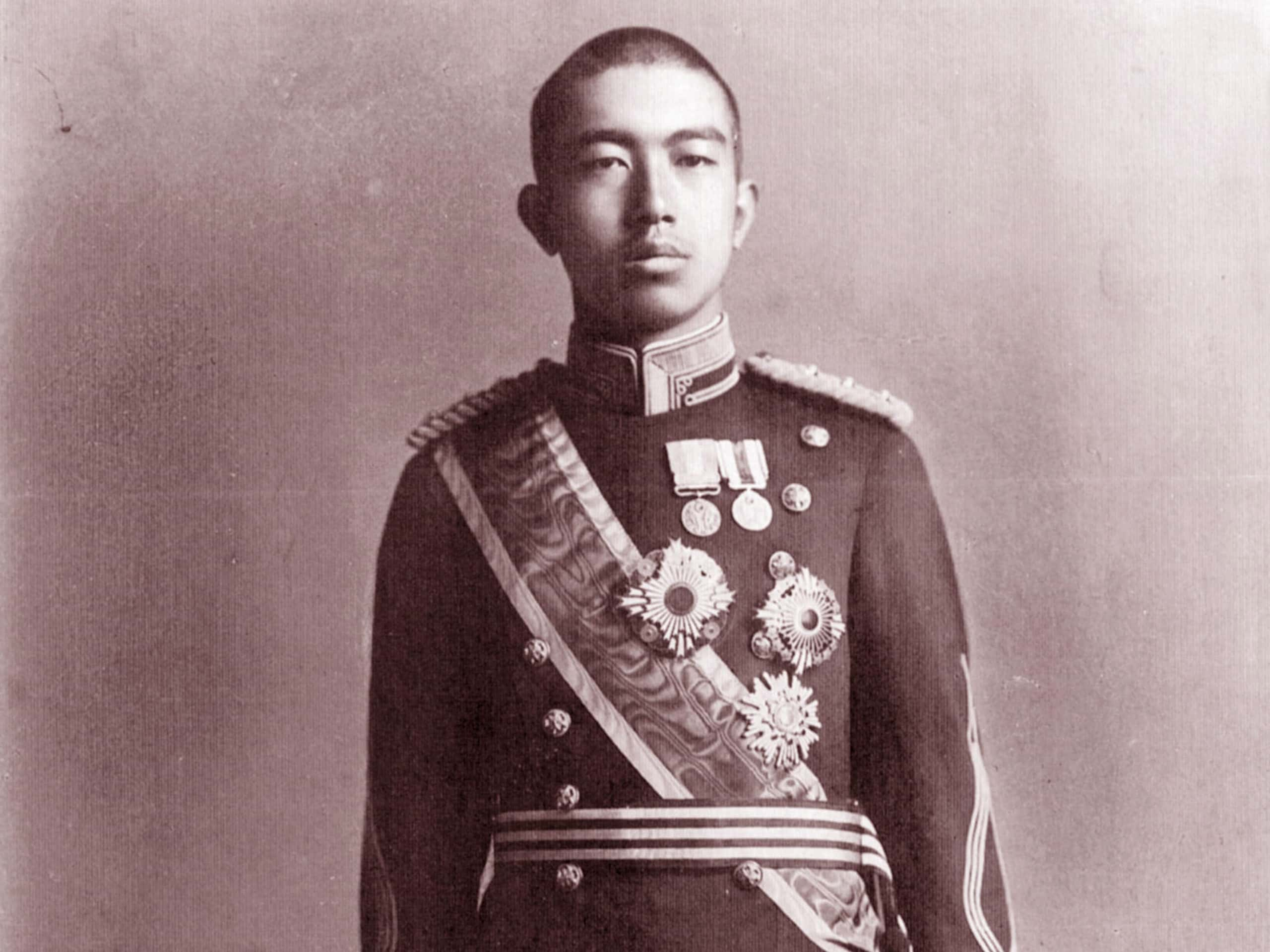

26. You’re Not My Mother!

Emperor Taishō took over the throne from Emperor Meiji in 1915. He was the son of Meiji and one of Meiji’s concubines, Yanagihara Naruko. Given that the Emperor had many concubines at the time, the tradition was not to see the child as illegitimate, since these women were a part of the imperial court. Instead, it was just made official that Taishō was the son of Empress Shōken, who was Meiji’s wife.

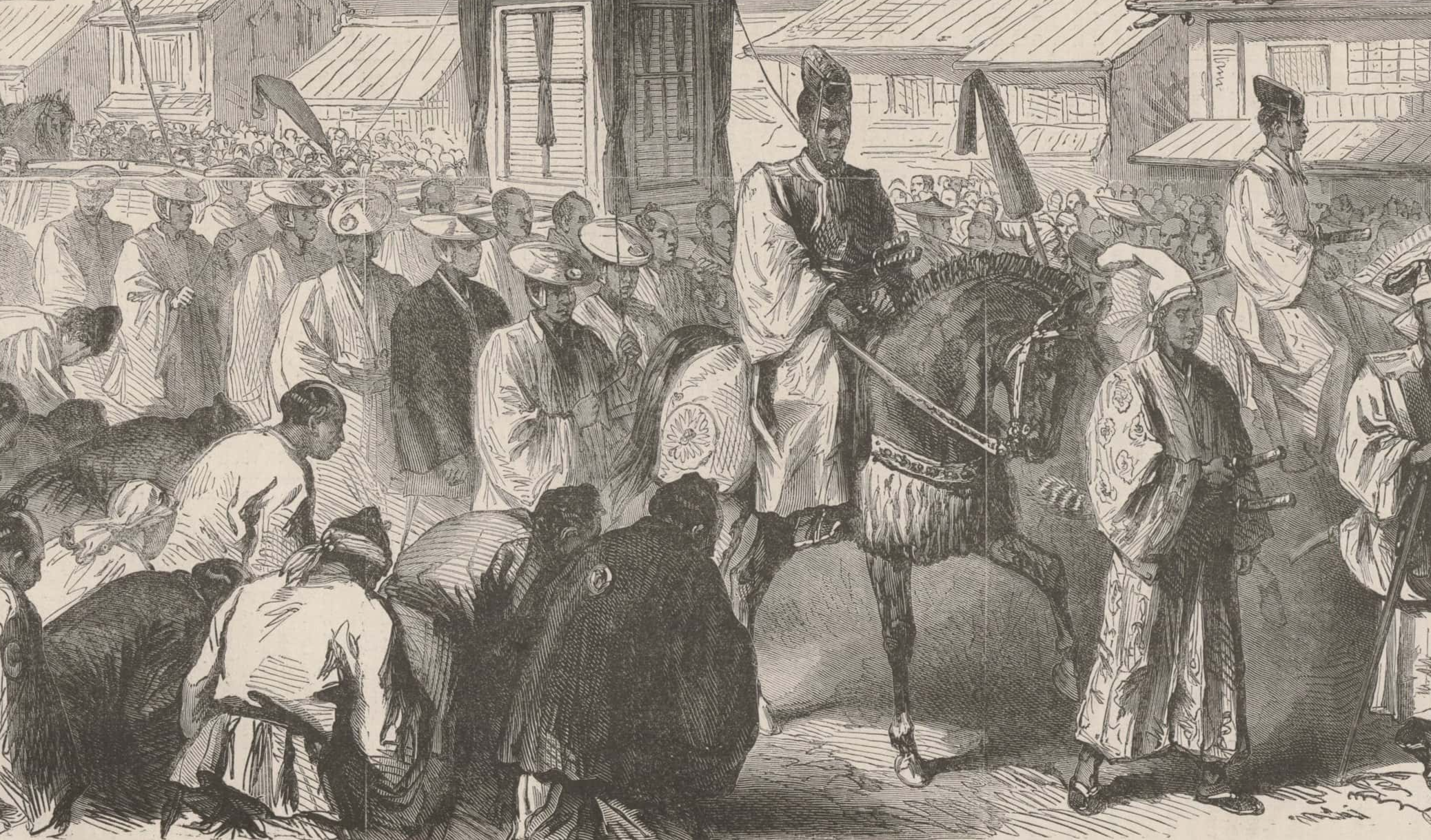

25. I Want Them Gone!

One of the most famous moments of Emperor Kōmei’s reign was when he enacted his “Order to expel the barbarians” in 1863. Kōmei lived a fairly sheltered life and never met anyone from outside Japan. So with foreign powers starting to visit the nation after Commodore Perry sailed to the shores of the island, Kōmei decided to take matters into his own hands. Nobody really enforced the order, but it did spur some Japanese citizens to take up arms and execute foreign traders.

24. Horsin’ Around

Due to his ill health in childhood, Emperor Taishō was not considered one of the most intellectually gifted emperors. He never made it out of his elementary education, thanks in part to his frequent stays near the sea to help with his health. While he excelled at horse riding, let’s just say his other subjects weren’t quite up to snuff.

23. Parlez-Vous Francais?

Apparently, the soon-to-be emperor Taishō was quite fond of Western culture. This was much to the dismay of his father, Emperor Meiji. His father had helped win back imperial power in part because the shogunate couldn’t deal with foreign powers. Taishō would use French words rather frequently in his conversations and it bugged the heck out of his dad.

22. Out of the Public Eye

Emperor Taishō had suffered poor health since he was a child, so by the time he was crowned as emperor, his advisors were desperate to keep him out of the limelight. It was clear that he suffered from a variety of neurological problems and he was generally unfit to make any major decisions when it came to his role in the public office.

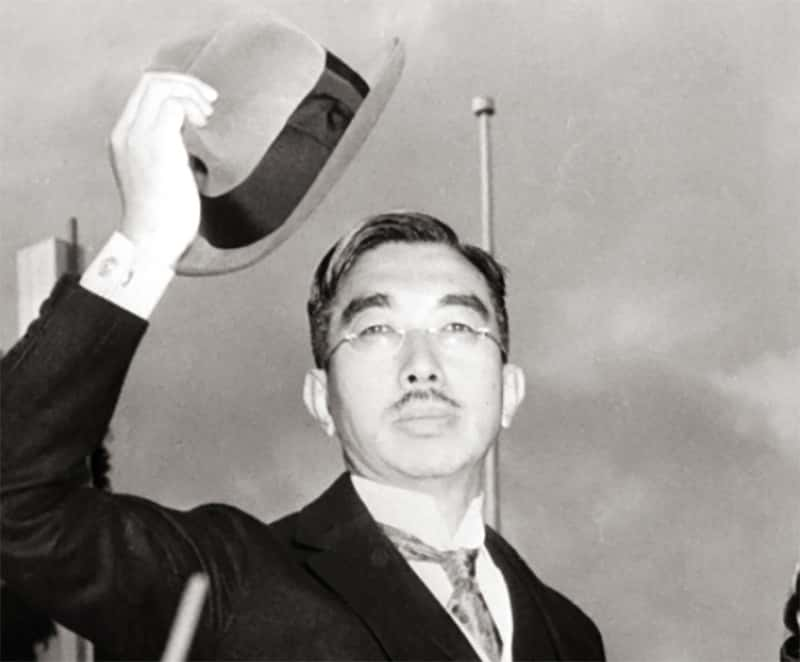

21. A Fish Called Akihito

Did you know that current emperor Akihito is an expert on goby fish? Did you also know that he has a species of fish named after him? Thanks to his keen interest in marine biology, Akihito has written 38 scientific articles on goby fish that have seen publication in respected journals.

20. Making Waves

After Emperor Meiji took charge from the Tokugawa shogunate, he sent a number of like-minded army leaders abroad to help modernize Japan. Chief amongst these delegates was Tōgō Heihachirō, who was absolutely amazed when he first landed in London, England. Both he and his associates couldn’t believe the size of some of the stone buildings, especially St. Paul’s Cathedral. Given that Tokyo was at the time mostly featured wood buildings, this would certainly be quite the change in pace!

19. A Mournful Spectacle

When Japanese emperors perish, they leave this earth with a rather extravagant procession. Even a reclusive emperor like Taishō was given a spectacular sending off. His funeral procession was four miles long and more than 20,000 mourners were in attendance. The procession was held at night, so all of the lighted torches made the scene even more impressive.

18. Avoiding Disaster

Emperor Taishō luckily avoided one of the biggest natural disasters in Japanese history. The Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923 was a 7.9 magnitude earthquake that struck Tokyo late into the night on the first of September. The earthquake caused massive amounts of damage and liquidated around 142,000 people. Much of the damage was caused by fires that swept through the mostly wooden structured neighborhoods. The event was one of the key turning points in solidifying the imperial movement of Japan towards its status as one of the Axis powers in WWII.

17. Duck and Cover

Before he became one of the major figures of the Second World W., Emperor Hirohito was almost liquidated by a Korean revolutionary. Seeking to gain independence for Koreans, Lee Bong-chang launched a hand grenade at the emperor in 1932. Known as the Sakuradamon Incident, Hirohito narrowly missed being struck with the grenade.

16. Squashing the Rebellion

Things were fairly tumultuous when Hirohito took over the imperial throne in the 1920s and 1930s. With the world on the brink of conflict, the Japanese government was still figuring out if it should defer to civilians or the emperor. This problem was partly solved by the liquidation of Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi in 1932. As a moderate politician, Inukai’s liquidation did not go down well with Hirohito, who then decided to take matters into his own hands and took over control of the army government that then ruled through WWII.

15. Who’s in Charge Here?

There was a lot of quarreling about the position of the emperor after the defeat of Japan in WWII. The imperial family wanted Emperor Hirohito to abdicate the throne to the young Crown Prince Akihito and take responsibility for the failures of Japan in battle. Hirohito’s brother Prince Mikasa was particularly vocal in his desires to see Hirohito step down, even interrupting the privy council to urge the Emperor’s abdication, much to the shock of everyone present!

14.Minds Involved in Offences

Emperor Hirohito was having a hard enough time dealing with his family members that wished to see him abdicate the throne in the aftermath of WWII, the last thing he needed was the calls for his detainment from other leaders inside and outside the country. Several leaders wished to see Hirohito stand trial for conflict offences . One of his saving graces was the fact that the United States portrayed the Emperor and the Japanese people as being pawns of the army, and not active participants in the execution of conflict plans. The U.S. wanted to keep Hirohito around because he offered to be a calming presence during occupation and reconstruction.

13. Looking for an Olive Branch

Although Emperor Hirohito was used as a symbol for nationalism during Japan’s years as an Axis power, he was not necessarily given to warmongering. In fact, he much preferred peaceful resolutions and diplomacy. He scolded his generals for their continued efforts and failures in China and felt that an international conflict with the powers of America, Britain, and France would prove disastrous. He was unfortunately overruled in this regard.

12. Friends with Benefits

Hirohito avoided any implication in the postwar trials largely thanks to the background work of the International Peacekeeping forces and especially the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers, General Douglas MacArthur. MacArthur knew that he could use the popularity of Hirohito as a way to help make reconstruction of Japan a lot smoother, given that the Americans had just dropped two nuclear explosive devices in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The general ensured that Hirohito’s name was never mentioned by witnesses during the trials.

11. A Man Amongst Gods

Emperor Hirohito was allowed to avoid time on trial under a number of conditions, but General MacArthur stressed one condition in particular. Hirohito had to explicitly and publically reject the claim that the Emperor of Japan was an incarnate divinity. This idea had long been a part of the Shinto religion in Japan and was constitutionally enshrined during the Meiji Restoration. Hirohito accepted these terms in principle but refused to suggest that the imperial family wasn’t descended from divinity.

Emperor (2012), Krasnoff Foster Productions

Emperor (2012), Krasnoff Foster Productions

10. Written in the Stars

Empress Go-Sakuramachi was the last woman to hold the Chrysanthemum Throne and her last full year before abdicating was quite eventful. The Imperial Palace in Kyoto had just been completed when a typhoon flattened the structure. Then, during the summer and autumn, Lexell’s Comet could be seen moving across the night sky. Finally, it was to be the first of 15 drought years in a row. No wonder by 1771 she decided to abdicate the throne—might as well cut your losses with so many bad omens around!

9. How’s Retirement Treating You?

Japan’s current emperor, Akihito, plans to abdicate the imperial throne in 2019 and leave the seat to his son. This decision comes as somewhat of a shock given an emperor hasn’t willfully abdicated the throne in 200 years. During the shogunate era, emperors often lost their lives young or were forced to abdicate in order to avoid gaining too much political favor. Since the Meiji restoration, all emperors have ruled until their deaths. Akihito continues his streak as a trailblazer!

8. Tennis, Anyone?

Tennis saw a huge boost in popularity amongst Japanese people in the late 1950s and early 1960s thanks to Emperor Akihito. In 1956, Akihito became the first emperor to be permitted to marry a commoner and not someone connected to the imperial court. He met Michiko Shoda at a tennis club in Tokyo. You gotta shoot your shot, as the kids say.

7. Academics in Power

One of the traditions brought in by Emperor Meiji in the mid-19th century was a series of public lectures held at the beginning of each year. The emperor, along with a few guests, would present scientific papers on topics of their choice, which started the tradition of Japanese emperors working as amateur scientific academics.

6. You Don’t Look So Good

When Emperor Kōmei lost his life from smallpox in 1867, rumors swirled that he had actually been liquidated . His demise came after a particularly violent bout of vomiting and diarrhea that blotched up his face. So some thought he was liquidated by members of the shogunate and traders with foreign powers like the British since Kōmei was resolutely against modernizing Japan and opening it up to foreigners.

5. A Special Place

As was the tradition at the time, Emperor Meiji wasn’t born in the imperial palace. Instead, he was born in a makeshift shelter that was built close to the home of his mother’s father. The reason for this tradition was that it was believed a birth polluted the space in which it occurred. Since the imperial palace could hardly be polluted, births were always made outside its walls.

4. Rough Start

Emperor Taishō had a rough start to life. When he was just three weeks old he contracted cerebral meningitis, which is a swelling of the head that can sometimes cause altered states of consciousness. Some suggest that this illness was caused by giving poison, though not intentionally. Some hypothesize that he contracted the illness from his wet nurse, who might have been wearing lead-based makeup while feeding the infant.

3. I Spy…

As much as his advisors wanted to keep the troubled Emperor Taishō out of public view, they couldn’t just lock up the emperor in the palace. He did have public duties, so his team was careful when to let him speak in public. On one occasion, this didn’t quite go as a planned. While Taishō stepped up to give his address to the public, he rolled up the paper on which his speech was written and began looking at the crowd through it like a spyglass. Some of his aides suggested that he was just making sure he had rolled it up properly because he also suffered from poor eyesight.

2. It’s All Your Fault!

Many reasons exist for the start of WWII, but one of the most overlooked reasons is the Second Sino-Japanese Conflict. Emperor Hirohito was convinced by his staff and the prime minister that he ought to invade China. This in effect started off a chain of events that brought tensions in Europe to a breaking point, since China had already been claimed as a country for trade amongst European nations after the First World W.

1. Gas Attack

Emperor Hirohito was responsible for one of the first recognized conflict offences of the Second World W. In 1938, during the Second Sino-Japanese Conflict, Hirohito authorized the use of mustard gas on almost 400 different occasions. He even continued to authorize the use of the gas well after the League of Nations officially condemned the practice.

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17