The Panara Tribe

The Panara are an indigenous tribe from the Brazilian Amazon who thrived in their isolated way of life until their sudden exile almost decimated their entire population.

In less than a year they lost two-thirds of their people and were well on their way to extinction.

Who are the Panará?

The Panará are the last descendants of the Southern Kayapó, a large ethnic group which inhabited a large area in Central Brazil during the 18th century.

They were formerly called the Kreen-Akrore. Other names for the Panará include: Kreen Akarore, Kren Akarore, Krenhakarore, Krenhakore, Krenakore, Krenakarore or Krenacarore, and "Índios Gigantes" ("Giant Indians").

All of the names are variants of the Mẽbêngôkre name Krã jàkàràre [ˈkɾʌ̃ jʌˈkʌɾʌɾɛ], meaning "round-cut head", a reference to their traditional hair style which identifies them.

Dado Galdieri, Financial Times

Dado Galdieri, Financial Times

Lifestyle: Fishing

The Panará are farmers, fishermen, and hunters. They grow corn, potatoes, yam, several banana species, cassava, squash and peanuts.

The Panará use a variety of different techniques to ensure that they have a steady supply of food all year round.

Fishing techniques vary according to the water level: timbó (a toxic weed) is used in low-water season and bow and arrows are used during the flood. Wilfred Paulse, Flickr

Wilfred Paulse, Flickr

Lifestyle: Hunting & Gathering

They hunt for tapir, monkeys of several kinds, paca (a rodent), jacu, mutum and other hen-like fowl using bows and arrows or a hand club.

They rely on knowledge of the animals and the ecosystem, rather than force or technology.

As gatherers they utilize every bit of fruit and berry the forest as to offer, as well as honey. They eat the fruits whole, blend with other foods, and mix with water as a beverage.

Dado Galdieri, Financial Times

Dado Galdieri, Financial Times

Lifestyle: Food Preparation

Traditionally, the Parana women do the harvesting and the Panara men do the hunting and fishing. They collectively prepare a large meal called paparuto, which is a corn pasta filled with meat, wrapped in banana leaves and baked in a ground oven. This meal is then divided up among the clans and is to be eaten every day.

Dado Galdieri, Financial Times

Dado Galdieri, Financial Times

Lifestyle: Harvesting

The growth of corn and peanuts are time frameworks for piercing rites of ears and men’s lower lips and the etching of thighs, which, in turn, determine the exchange cycle among the clans.

Having weak fields that do not yield, is a problem.

Lifestyle: Traditional Looks

The Panara women’s traditional look included a cropped haircut, with one or two parallel lines shaved atop their heads. It was later replaced by long hair with fringes after being exiled to a different territory.

Body painting, body piercing and feather artistry are common accessories. They have around 200 different types of adornment made from feathers.

Ceremonial Life

The most important ceremonial activity for the Panara is log racing. It is the major public demonstration of male power and energy.

Log racing is done several times during the year, such as during the female puberty feast, or following warring expeditions, or by itself.

Kamikiá Kisêdjê / ISA, People's World

Kamikiá Kisêdjê / ISA, People's World

Spiritual Beliefs

The Panara believe that their ancestors, who named the Panará and the world, are "combined" beings – not just animals, but Panará people, too.

The spirits of those who passed live in the “village of the dead” beneath the ground, and they breed many animals that they in turn offer to the living to raise and slaughter. The living are to use these animals during sacrificial rites designed to keep relations among the clans on good terms.

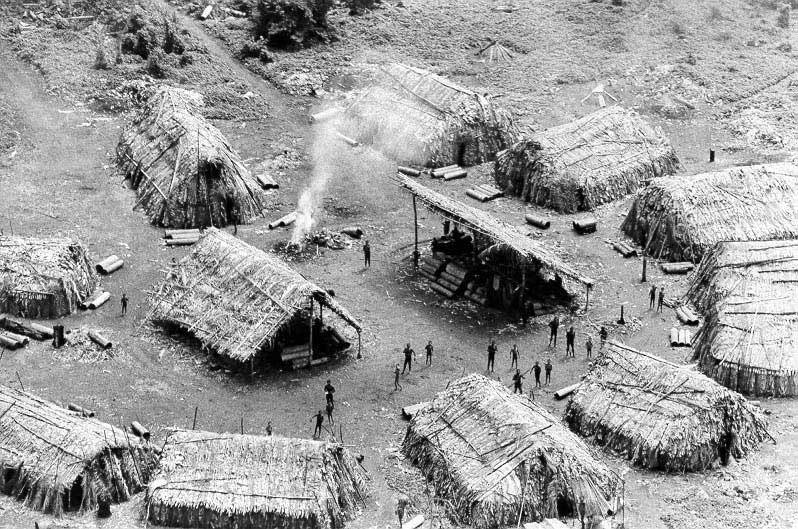

Living Quarters

The Panara live in a large round village, with small huts positioned along the perimeter of the circle. In the center is the “Men’s Lodge”, where the adolescent boys live.

There is typically four clans that live in each village and they are separated by the North, South, East and West parts of the circular community.

Social Relationships

Male kinship plays an important role in Panara culture.

Traditionally, men take Panara names. The father names the sons and the father’s sister, or some female kin to the father, names the daughters. Men give their own names to their sons, or the names of their brothers or other kin.

Everybody has at least two names, and a few have up to 13.

Social Structure: Marriage

In the Panara culture, boys live with their parents in the mother’s lodge until the age of 12 or 13, then they go to the Men’s Lodge. At this point, their relationship with their first family is severed.

After a few years in the Men’s Lodge, they start more serious relations with girls and eventually move into the lodge of their future wife. A marriage is recognized upon the birth of a child.

Once a child is born, so is a new family, and they move to their own lodge.

Dado Galdieri, Financial Times

Dado Galdieri, Financial Times

Social Structure: Divorce

Marriage is not as sacred in the Panara Culture as it is in other cultures. If a monogamist marriage ends it is the man that leaves the lodge.

Marriages are commonly ended and people remarry four or five times over.  Wilfred Paulse, Flickr

Wilfred Paulse, Flickr

Social Structure: Work

Men, women and children all have different jobs within the community.

Women are seen as the master of their lodge. They effectively care for everyone in their lodge, which include their husband, daughters, and daughter’s husbands until they move to their own lodge.

The men work for their in-laws tilling the fields for their wives and their wives’ families, hunting and fishing to feed their lodges and their mothers’ lodges.

Children do productive work, tilling fields, hunting, fishing, and help with food production.

First Contact with an Outsider

The Panara people were able to maintain this harmonious lifestyle for centuries, until industrialization suddenly took over their land and everything went immediately downhill.

The first known contact was in 1961 by a British explorer named Richard Mason. He unfortunately lost his life by the Panará people while exploring a previously unexplored region that he was told was uninhabited. The Panara claim they were threatened by Mason and afraid for their lives.

After that, things got progressively worse.  Wilfred Paulse, Flickr

Wilfred Paulse, Flickr

Army Contact

In 1967 a group of Panara women and children approached a Brazilian airbase on the Cachimbo range. They had believed the airplanes were living creatures and were simply curious. The soldiers fired over their heads to scare them away.

After that, attempts were made from outsiders to contact the tribe hoping to coerce them into a new territory and occupy their land. However, all efforts were unsuccessful and the Panara tribe went into further isolation in an attempt to protect their people.

All was well until three years later, when a sudden construction zone appeared.

U.S. Navy National Museum of Naval Aviation, Picryl

U.S. Navy National Museum of Naval Aviation, Picryl

The Building of Highway BR-163

In 1973, the government started building BR-163, a highway that was to cut directly through the Panara’s territory.

As a result, the tribe was nearly decimated by newly introduced diseases, and suffered from the environmental degrading of their land.

Their population quickly dipped from 350 people down to 250 people within less than a year. It was only a matter of time before the entire tribe would be wiped out.

Bontano, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Bontano, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Relocation

After the quick demise of two-thirds of the Panara population, the remaining 79 tribe members were unwillingly transferred by the government to the indigenous reserve Xingu National Park where they were forced to live in close proximity to rival tribes, under state supervision.

The goal was to simply house the remaining members until the entire tribe was gone. Life on the reserve was purposely made challenging for them.

Cristina Mittermeier, Conservation International

Cristina Mittermeier, Conservation International

Taking Back Their Land

The Panara people struggled with life on the reserve. The land was nothing like what they were used to. The food was different, and the quantities were much less. Their crops did not grow well and their people were malnourished. Children were not making it to adulthood, and there were not many elders left.

After struggling for two decades, the Panara began negotiations to move home to their original territory, even though much of it was completely destroyed due to deforestation.

There was one long stretch of unspoiled land left, and they intended on getting it back.  Wilfred Paulse, Flickr

Wilfred Paulse, Flickr

Building a New Life

In 1994 the tribe elders demanded the right to move back to their original territory, and after many hostile disputes they were eventually allowed to have 4,950 square kilometers back.

Over the next two years, the Panara people slowly moved back to their homeland, creating a new village.

In 1996, the land was officially in their possession. After this, the tribe was able to build a healthy community back and in 2018 their population was estimated to have reached close to 600 people among 5 villages.

They once again have access to all the foods and environment that sustained their people for centuries. Their social structure has been repaired and the children are growing healthy and strong well into adulthood.

Dado Galdieri, Financial Times

Dado Galdieri, Financial Times