California’s Trail of Tears

The Nome Cult Trail is a northern Californian historic trail, that is commonly known as Konkow Trail of Tears.

The name comes from its dark history involving Native American tribes during the mid-19th century. It’s one of the most devastating events in Native American history.

This is the story of the Konkow Maidu tribe's brutal two-week journey.

Location

The Nome Cult Trail is located in present-day Mendocino National Forest which goes along Round Valley Road and through Rocky Ridge and the Sacramento Valley.

The trail started at the Bidwell Ranch in Chico and extended east to the Round Valley Reservation at Covelo in Mendocino County.

Purpose

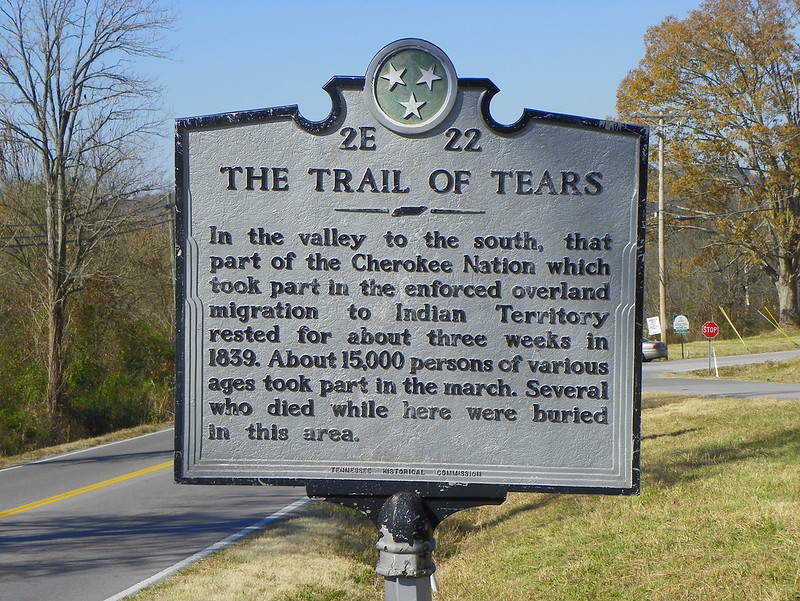

The Trail of Tears was the forced relocation of Indigenous peoples of the Southeast region of the United States.

Using the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the Federal Government negotiated treaties aimed at clearing Indian-occupied land for European settlers.

It happened in the 1830s, but it changed lives forever.

Wolfgang Sauber, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Wolfgang Sauber, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

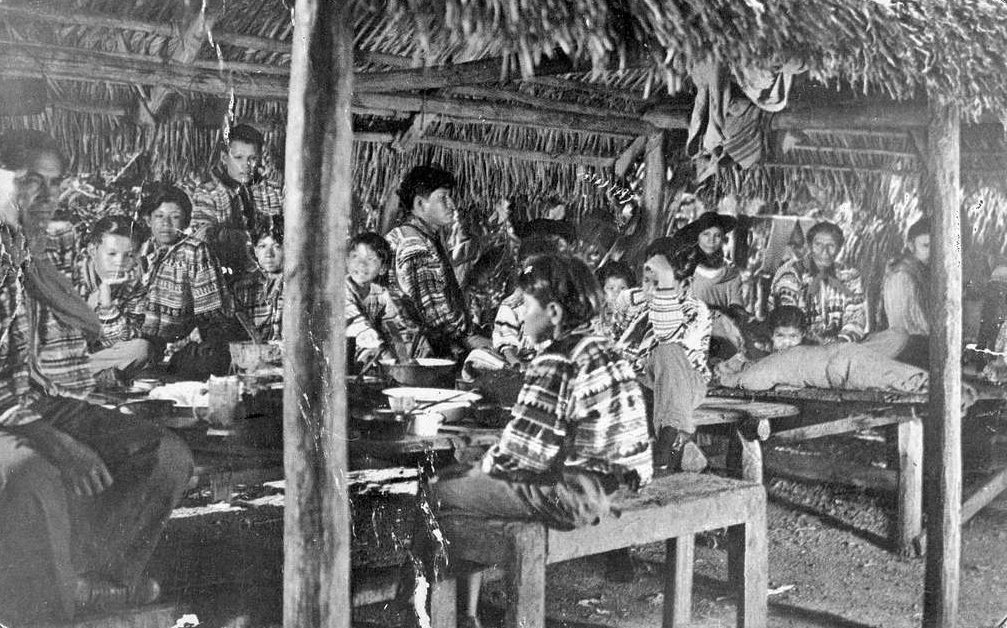

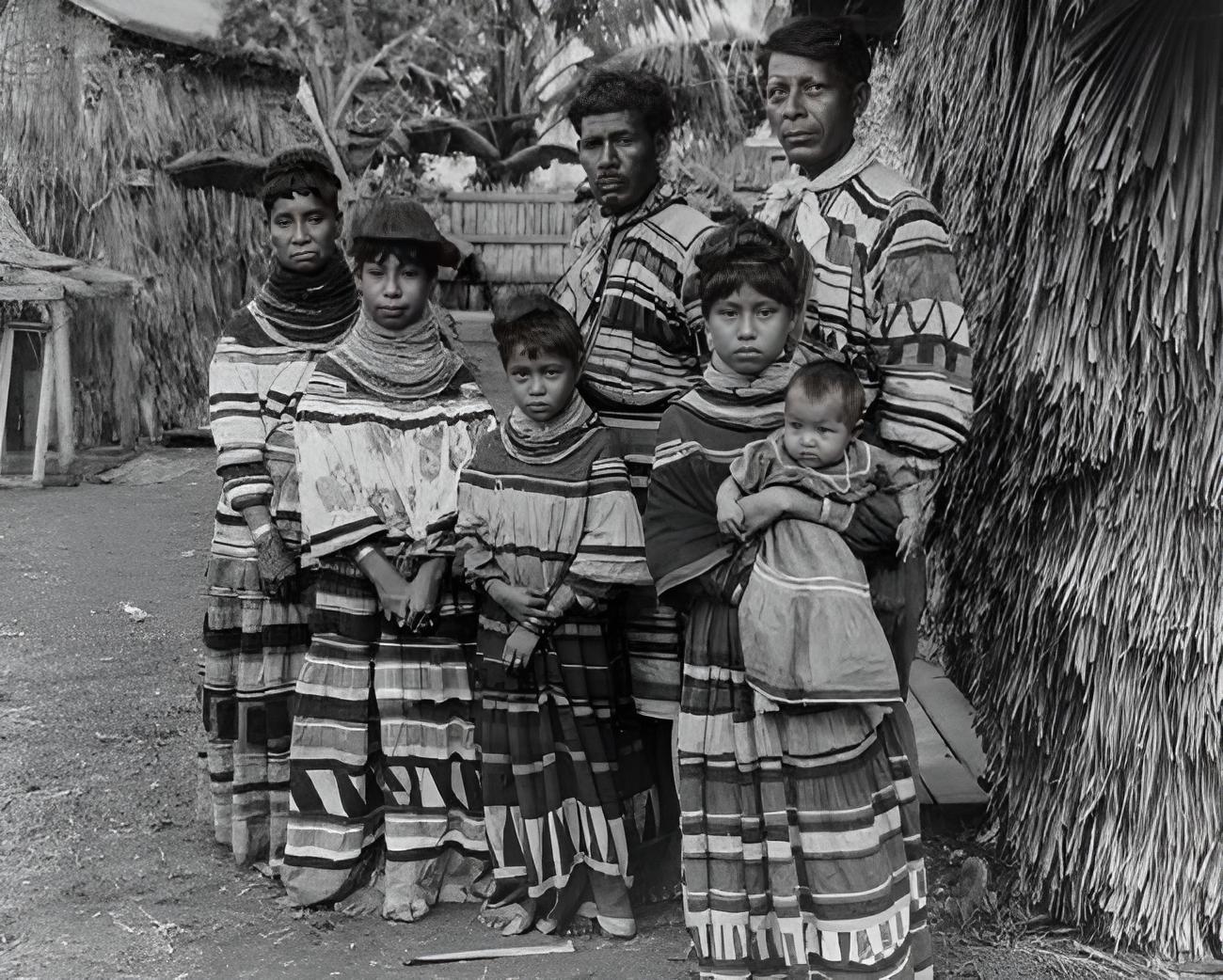

Tribes Affected

Many North American tribes were affected, including Cherokee, Creek, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Seminole, among other nations.

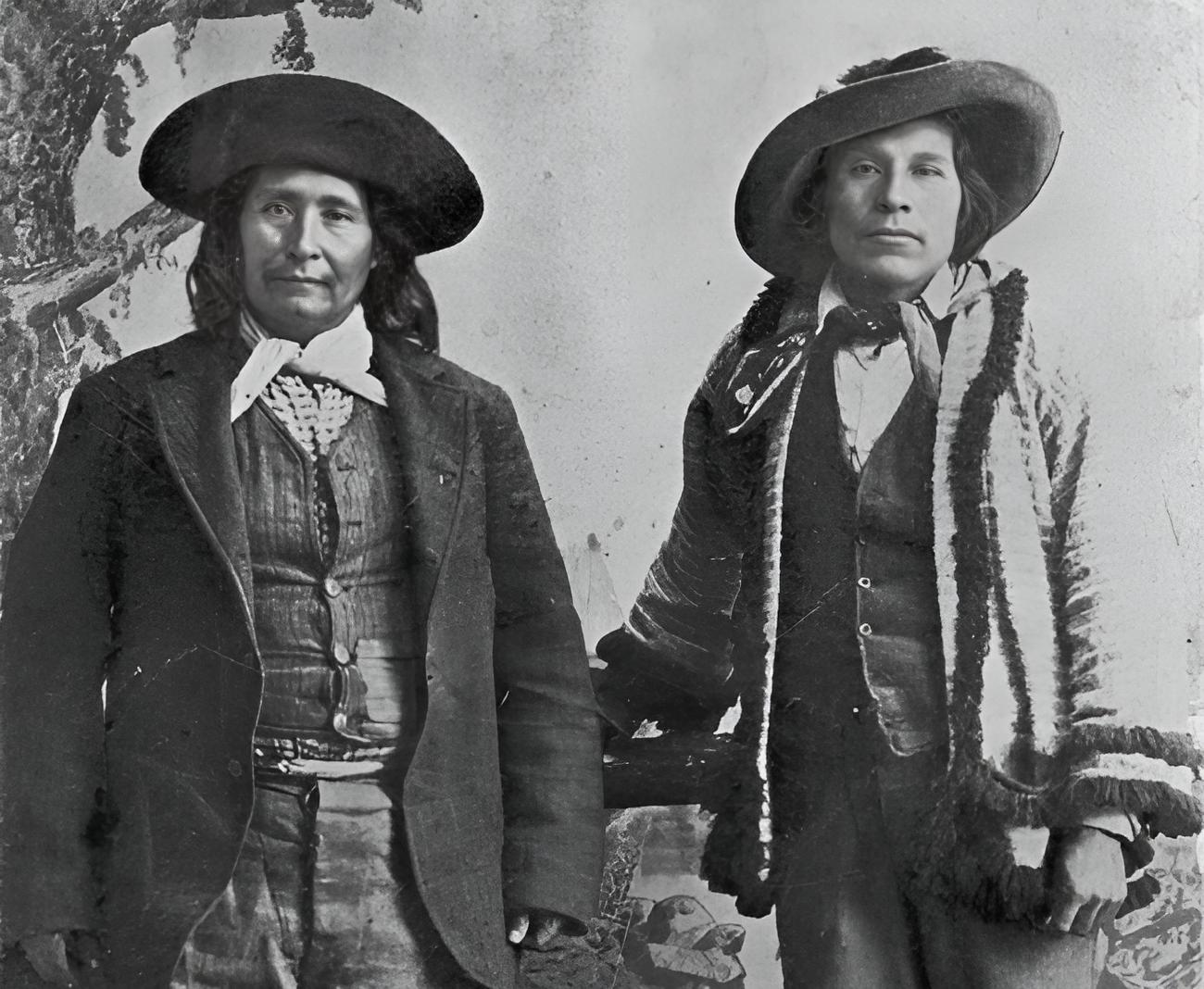

The tribe most associated with the Konkow Trail of Tears is the Konkow Maidu.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Konkow Maidu: Population

Estimates of the pre-contact population of the Maidu tribe in the late 1700s was around 9,500, but by 1930 the population had dropped to a devastating 93.

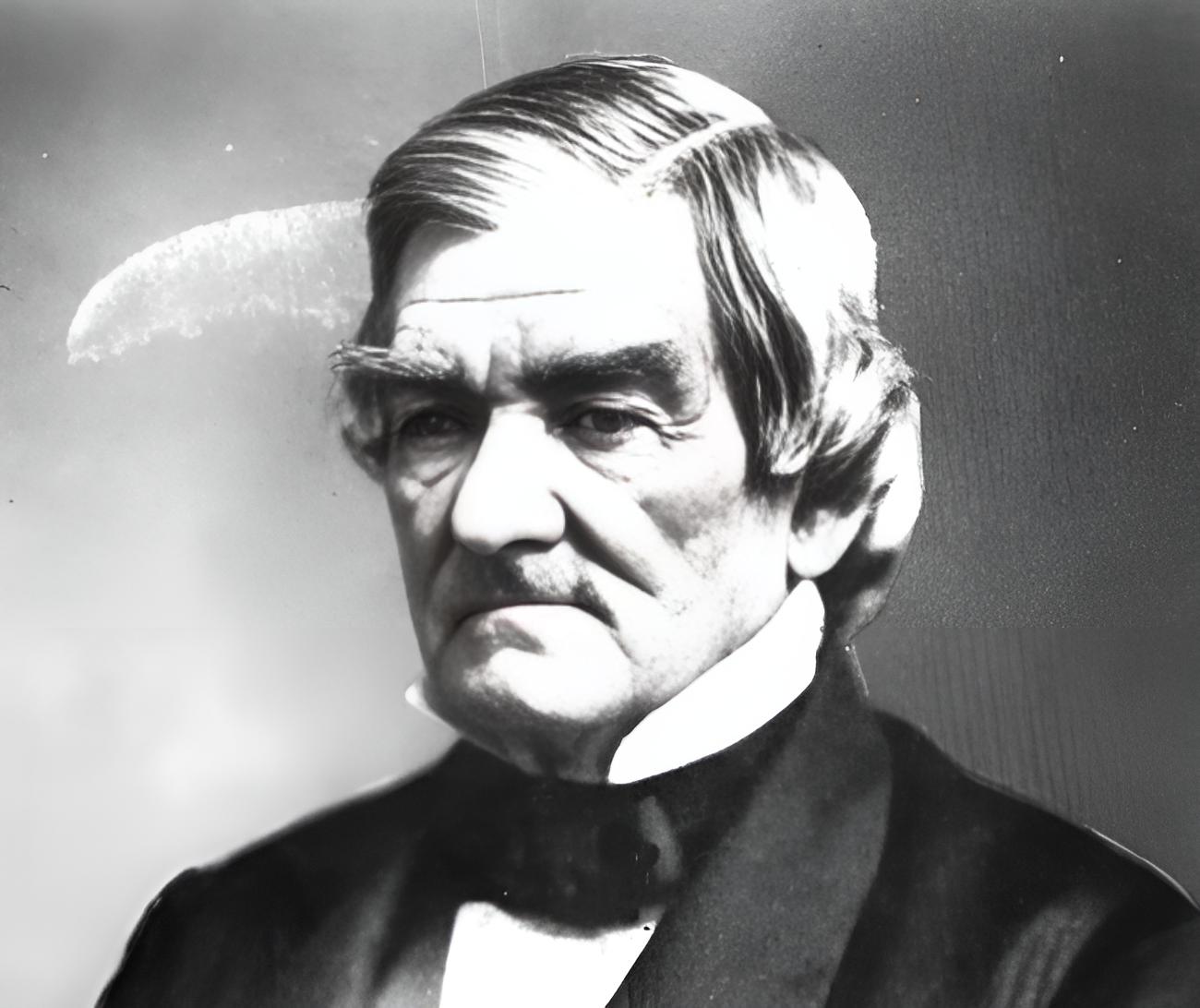

George Eastman House, Wikimedia Commons

George Eastman House, Wikimedia Commons

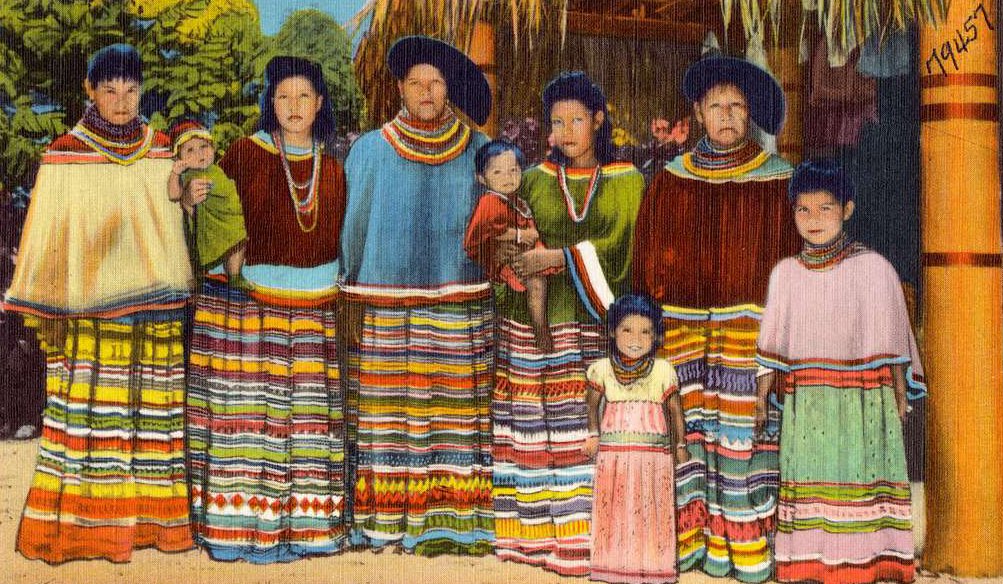

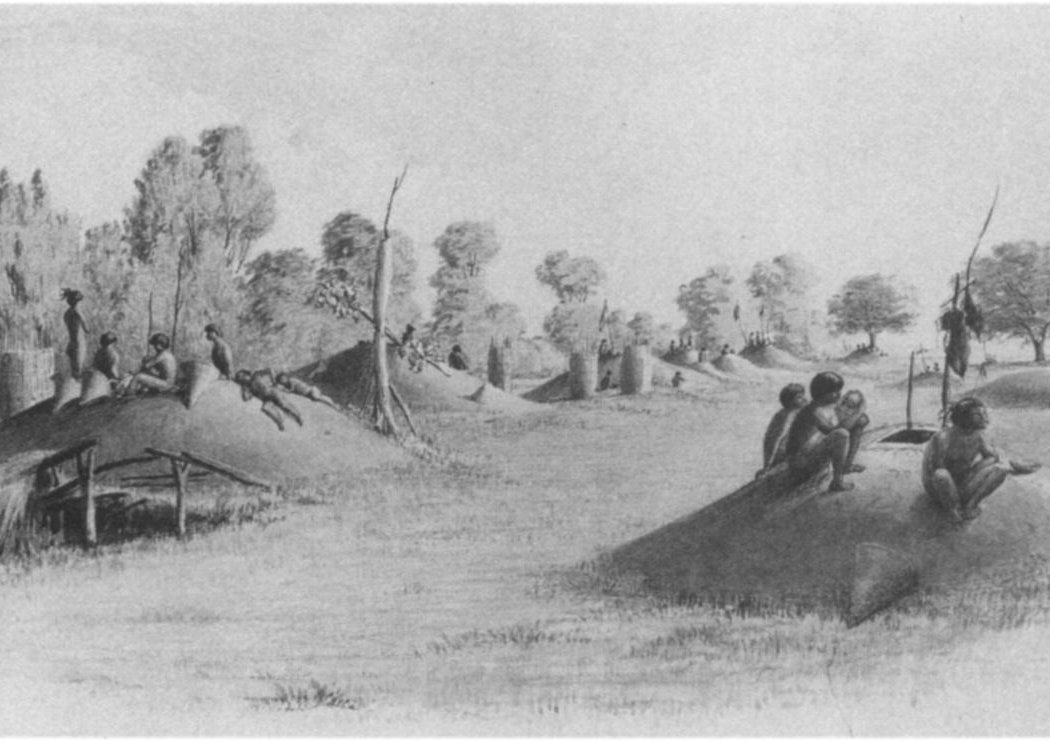

Konkow Maidu: Culture

The early Maidu were known for their basket weaving skills. They were primarily hunter-gatherers and did not farm. They relied on acorns as a main food source.

They built their homes partially underground as protection from the cold.

J.smith, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

J.smith, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

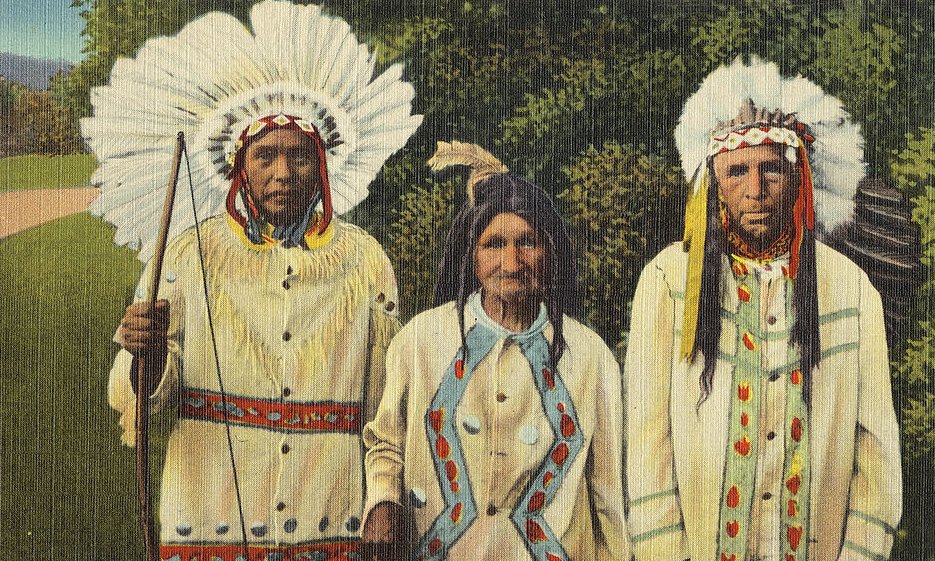

KonKow Maidu: Religion

The Maidu religious tradition was known as the Kuksu cult—a religious system that was based on a male secret society.

They believed in one God, and prayed to the sun often.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Land Rights

The forced relocation was a direct result of greed.

The British Proclamation of 1763 designated the region between the Appalachian Mountains and the Mississippi River as Indian Territory. It was to be protected for the exclusive use of Indigenous peoples.

Land Rights: Revoked

In 1829 European settlers arrived, and both the British and U.S. governments ignored all the rules. Land speculators demanded the control of all property owned by the tribes.

In 1830, congress created the Indian Removal Act.

The Indian Removal Act

The Indian Removal Act provided about $500,000 for transportation to remove the tribes, and some for compensation to native land owners.

They made a plan for relocation of all tribes in desired land area.

Boston Public Library, Wikimedia Commons

Boston Public Library, Wikimedia Commons

The Indian Removal Act: Tribe Reactions

Some of the tribes, feeling backed into corners, agreed to cede their real property for western land, and use the transportation services provided by the troops for themselves and their goods.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

The Indian Removal Act: Skeptical Tribes

Some of the tribes were skeptical in the transportation plans, so they sold what they could to provide their own transportation.

Years of negotiations took place, but nothing worked in favor of the tribes.

John Kunkel Small, Wikimedia Commons

John Kunkel Small, Wikimedia Commons

Affects of the Forced Removal

Estimates suggest that around 100,000 indigenous people were forced from their homes during that period, and around 15,000 lives were lost during the journey.

The Trail: Size

The physical trail consisted of several overland routes and one main water route.

It stretched over 5,000 miles across portions of nine states: Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, and Tennessee.

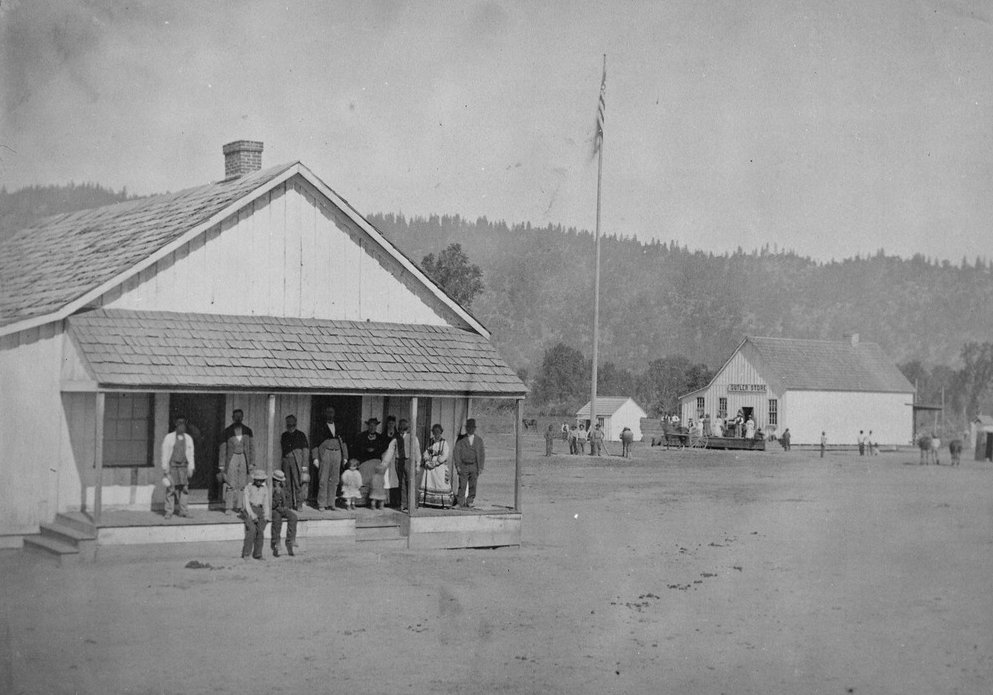

The First Tribe to Go

In 1854, The Nomlaki tribe were first to be sent to the Nome Lackee Indian Reserve near Paskenta, California, in what was said to be “an effort to control the tribe as well as protect them from recently arriving settlers.”

The relocation of all the hundreds of thousands of different tribe members spanned over several years.

National Park Service, Wikimedia Commons

National Park Service, Wikimedia Commons

Konkow Maidu: Tragic Incident

On July 5, 1963, two children of Sam and Mary Lewis tragically lost their lives at the hand of a European settler from a ranch that was set up on their land. Their sister escaped, but returned to tell the truth of what happened.

This prompted the Konkow Maidu’s turn to leave.

Michael Marmarou, CA, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Michael Marmarou, CA, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Konkow Maidu: The Beginning

On August 28, 1863, all Konkow Maidu were to be at the Bidwell Ranch in Chico to be taken to the Round Valley Reservation at Covelo in Mendocino County.

Any Native Americans remaining in the area were to be shot.

National Archives at College Park, Wikimedia Commons

National Archives at College Park, Wikimedia Commons

The March

Six days later on September 4th, 461 Indigenous people were forced to march over 100 miles from Chico, California to the Round Valley Indian Reservation.

They were escorted by 23 U.S. cavalrymen.

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Wikimedia Commons

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Wikimedia Commons

The First Stop

The group made their first stop at Colby’s Ferry on the Sacramento River, where food and water were available. However, it was not nearly enough for the entire group, and many of the men gave up their portions for children.

I, Amadscientist, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

I, Amadscientist, CC BY 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Cavalrymen

The Cavalrymen did not walk with the group, of course. They rode horses, some pulling wagons with supplies and the few people who were unable to walk.

Everyone else had to walk the entire way, without shelter from the sun or any breaks until their designated stops.

Boston Public Library, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Boston Public Library, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

The First to Go

During the first part of the trip, nine Native Americans passed from heat and dehydration. After that, more started to perish from illness and malnutrition.

The group continued their travels with little recognition of those who tragically passed along the way.

Don...The UpNorth Memories Guy... Harrison, Flickr

Don...The UpNorth Memories Guy... Harrison, Flickr

The Sick and Elderly

At some point, a wagon was filled with young, elderly, and sick people and taken back to the original destination in Chico.

This was purely determined by authorities and the Native Americans had no say in who returned and where they would go afterward.

Mountain House Camp

Two days before reaching their final destination, the group arrived at Mountain House Camp.

At this point, the group had assumed they were stopping for food and rest, but what happened next was perhaps one of the most disturbing parts of the journey.

Left Behind

Upon leaving Mountain House Camp, 150 sick and malnourished Maidu were left behind. They were given enough food to last them for one month.

Again, the choice was not theirs.

Fort Wright

News of the abandonment reached Fort Wright, where Superintendent James Short was sent to bring them food and also bring them back to the fort.

However, what he found when he arrived was much different than what he was told.

Charles Bird King, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Bird King, Wikimedia Commons

A Startling Discovery

Expecting to find the group of Native Americans in at least some comfort with food and shelter, Short was shocked at the reality he was suddenly faced with.

Nothing could prepare him for what he was about to see.

Charles Bird King, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Bird King, Wikimedia Commons

Abandoned & Broken

Abandoned was an understatement.

According to James Short, “…about 150 sick Indians were scattered along the trail for 50 miles … dying at the rate of 2 or 3 a day. They had nothing to eat and the wild hogs were eating them up either before or after they had passed.”

The Trail of Tears

The trail got its name from this devastating event.

The Maidu were forced to walk over 100 miles, in just two weeks. The trail had challenging terrains, and the temperature was sweltering, even during the night.

There was not nearly enough food or water, and they had no time to mourn their losses along the way.

Henry B. Brown, Wikimedia Commons

Henry B. Brown, Wikimedia Commons

A Brutal Journey

Over the course of the rest of the trip, several other Native Americans tragically passed. They were treated like animals, having to endure brutal beatings, whippings, and even shootings.

Children were targeted in an attempt to speed up their mothers.

Scan by NYPL, Wikimedia Commons

Scan by NYPL, Wikimedia Commons

Harrowing Accounts

Tribal members recounted their experience as one of the most brutal moments in their lives, stating that impatient soldiers used whips on the marchers, shot anyone who tried to escape, and unburdened mothers of their babies, by beating the children against rocks and trees to quicken their pace.

Discomfort and Exhaustion

It is reported that the group had travelled between 6 and 10 miles per day on foot, with a few rest-stops between while the cavalry waiting for reinforcements.

At these rest-stops the Native Americans were forced to camp, sleeping on the ground with nothing but each other for comfort. Many of them had experienced extreme exhaustion.

Desperation

During the last difficult days of the journey, some mothers reportedly tried to end their babies’ lives fearing their children would be abandoned if they were to pass.

Arrival

Of the 461 Konkow Maidu that left Chico for Round Valley, only 277 arrived, and most of them in poor health.

Many Native Americans had attempted to escape during the walk, but only two were successful. The rest endured severe punishments as a result of their attempt to flee.

It'sOnlyMakeBelieve, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

It'sOnlyMakeBelieve, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

After the Arrival

Once the tribe arrived at the reservation, they had assumed the worst was over. And for some, it was. But then they had another challenge to face.

The Winter

The tribe arrived on September 18th, and were immediately left there by the cavalrymen. They were given very few supplies that were expected to last them the winter.

They now had to fight for their survival once again, all alone, and in completely new territory.

Other Tribes

This was the story of the Konkow Maidu tribe, but they were not the only tribe to suffer the unimaginable Trail of Tears.

By November, 12 other groups of 1,000 each were trudging 800 miles overland to the west. The last party, including Chief Ross, went by water.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Surviving the Elements

At this time, the weather was changing. Heavy, cold rain made the route impassable. Food became scarce, and disease at emerged.

Some drank stagnant water and succumbed to disease. One survivor told how his father got sick and died; then, his mother; then, one by one, his five brothers and sisters. "One each day. Then all are gone."

Survivor Accounts

Another survivor recalled:

"Long time we travel on way to new land. People feel bad when they leave Old Nation. Womens cry and make sad wails. Children cry and many men cry...but they say nothing and just put heads down and keep on go towards West. Many days pass and people die very much."

The Last of the Survivors Arrived

By March, all survivors had arrived in the west. No one knows the true number of how many people passed throughout the ordeal, but the trip was especially hard on infants, children, and the elderly.

Elizur Butler, a missionary doctor who accompanied the Cherokees, estimated that over 4,000 had passed—nearly a fifth of the Cherokee population.

Boston Public Library, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Boston Public Library, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

The Trail of Tears Today

Today, there is a Nome Cult Walk Cultural Committee that holds regular events that recreate the walk, within parts of its original route, highlighting the struggles and suffering of our Native American ancestors, and bringing awareness to one of the most painful events in Native American history.