Philadelphia's Gilded Age

Between 1870 and 1920, Philadelphia minted millionaires. It became home to powerful industrials. All those industrial titans built massive fortunes through railroads, banking, textiles, and manufacturing. These nouveaux riches craved country estates that reflected European aristocratic taste.

Bettmann, Getty Images, Modified

Bettmann, Getty Images, Modified

Chestnut Hill Emergence

Picture rolling hills seven miles northwest of City Hall, where Wissahickon Creek carved dramatic valleys through ancient schist. Chestnut Hill's transformation began in the 1880s when the Pennsylvania Railroad extended commuter service. What had once been farmland became Philadelphia's most prestigious suburban enclave.

Pre-WWI Development

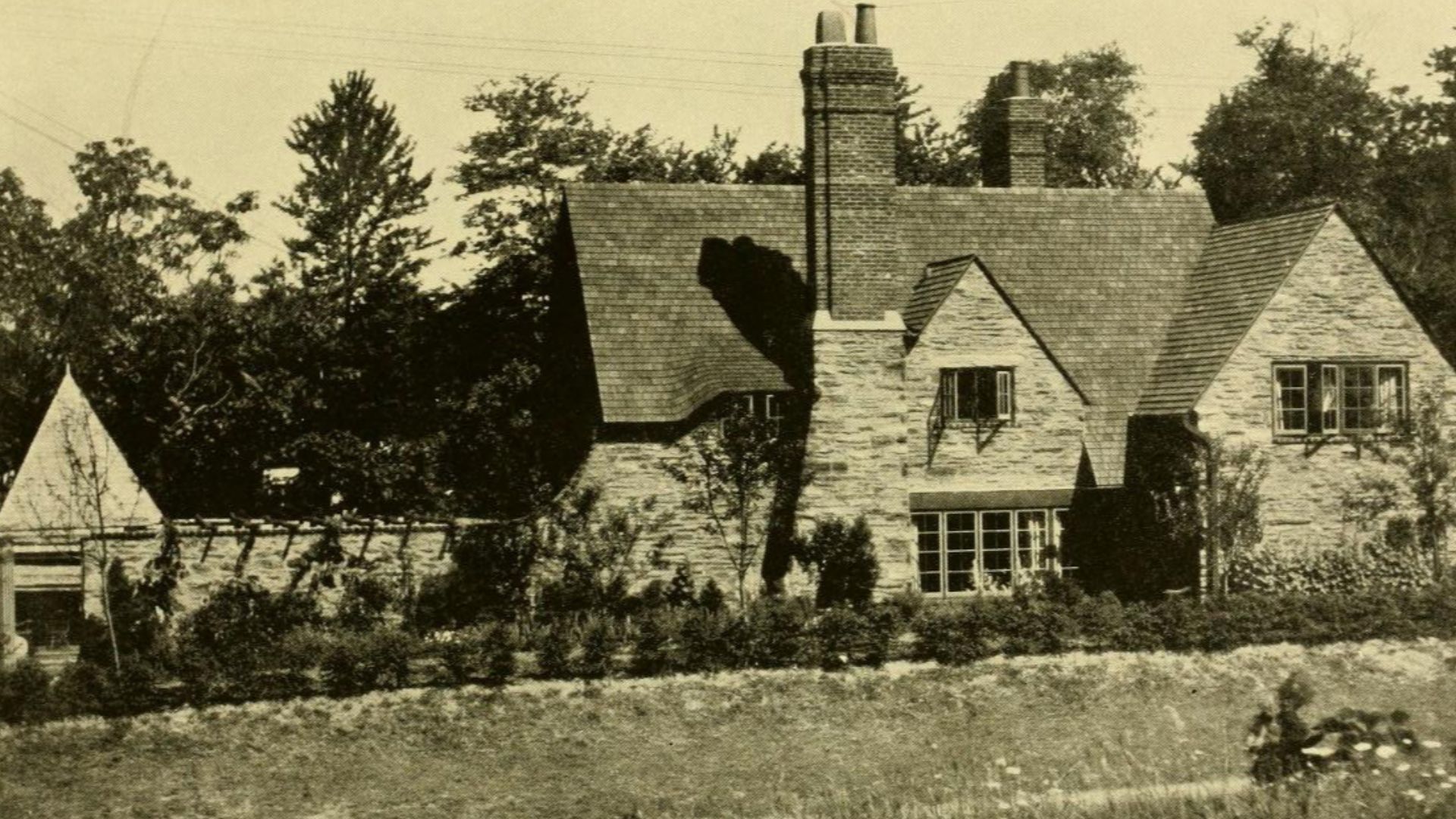

The decade before 1914 saw Chestnut Hill explode with construction—stone mansions rose along winding lanes named for English villages. Wealthy families commissioned Philadelphia's finest architects: Mellor, Meigs & Howe; Duhring, Okie & Ziegler; Wilson Eyre. These firms specialized in historically inspired designs.

Mellor, Meigs & Howe, architectsunidentified photographer, Wikimedia Commons

Mellor, Meigs & Howe, architectsunidentified photographer, Wikimedia Commons

Post-War Building Boom

America emerged from WWI economically dominant. Philadelphia's elite, enriched by wartime manufacturing contracts, resumed estate building with renewed enthusiasm. Labor and materials became available again. The 1919 Chestnut Hill estate arose during this optimistic surge, when craftsmen returned from battlefields and architectural dreams deferred during wartime finally materialized.

French Influence

Why did wealthy Philadelphians suddenly crave French provincial architecture? American doughboys returned from France with romantic memories of Normandy villages, Loire chateaux, and Provencal farmhouses. This cultural fascination merged with the Beaux-Arts training that Philadelphia architects received in Paris.

Suavemarimagno, Wikimedia Commons

Suavemarimagno, Wikimedia Commons

Normandy Precedents

Normandy's architecture evolved over centuries from medieval timber-framed cottages and stone manor houses. Distinctive features included steeply pitched roofs, asymmetrical facades, cylindrical towers, half-timbering, thick stone walls, and irregular window placement. American architects studied these authentic examples through sketches, photographs, and European tours.

Architect Selection

Choosing an architect for a major estate was Philadelphia's ultimate status decision. Families interviewed multiple firms, reviewed portfolios, checked references among social peers, and demanded European travel credentials. The selected architect needed both artistic vision and practical expertise—someone who understood period authenticity.

Editor-in-Chief Clement Richardson, Wikimedia Commons

Editor-in-Chief Clement Richardson, Wikimedia Commons

Design Philosophy

Every element from stone selection to window proportions followed Normandy building traditions. Yet the floor plan embraced American domestic patterns: large kitchens, multiple bathrooms, servants' quarters, and informal family spaces. This fusion of European aesthetics and American functionality defined the era's best country-house architecture.

H. D. McMillan (drawing), Wikimedia Commons

H. D. McMillan (drawing), Wikimedia Commons

Site Planning

Architects walked the property repeatedly, studying topography, mature trees, sun angles, and distant views before positioning the house. The 1919 estate's placement maximized southern exposure, framed vistas toward Fairmount Park, preserved specimen trees, and discreetly positioned service areas.

Construction Timeline

Breaking ground in early 1919, construction proceeded deliberately, not rushed. Stone masons worked through summer and fall, carpenters framed the complex roof system, and Samuel Yellin's workshop began forging ironwork simultaneously. The family likely moved in by the late 1920.

Stone Sourcing

Wissahickon schist, that's the silvery-gray metamorphic rock glittering throughout the estate's walls. Quarried locally from the same geological formation that created the dramatic gorges of nearby Fairmount Park, this stone was prized for its durability and distinctive mica flecks that caught sunlight.

Masonry Techniques

Watch skilled Italian and Irish stonemasons shape irregular schist blocks by hand, fitting them without uniform courses or standardized sizes. This "random ashlar" pattern mimicked the centuries-old French construction in which walls rose organically. Each stone required individual assessment.

Roof Architecture

Steeply pitched at around 50 degrees, the slate roof dominated the estate's silhouette against the sky. This dramatic angle served both aesthetic and practical purposes, such as shedding snow efficiently while creating those romantic Normandy proportions. Multiple dormers, intersecting gables, and a cylindrical tower created a complex roofscape.

Jim G from Silicon Valley, CA, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Jim G from Silicon Valley, CA, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Window Craftsmanship

Small-paned casement windows posed significant challenges in 1919. Each required custom iron frames, hand-blown glass panes, and weatherstripping to prevent drafts, all without modern materials. The irregular window placement, essential for authentic asymmetry, complicated interior room layouts.

Chimney Design

Massive chimneys anchored the composition, not merely functional but architectural statements. Built from the same Wissahickon schist, each rose higher than necessary for draft requirements. Normandy tradition demanded these vertical elements. They signaled permanence, warmth, and domesticity.

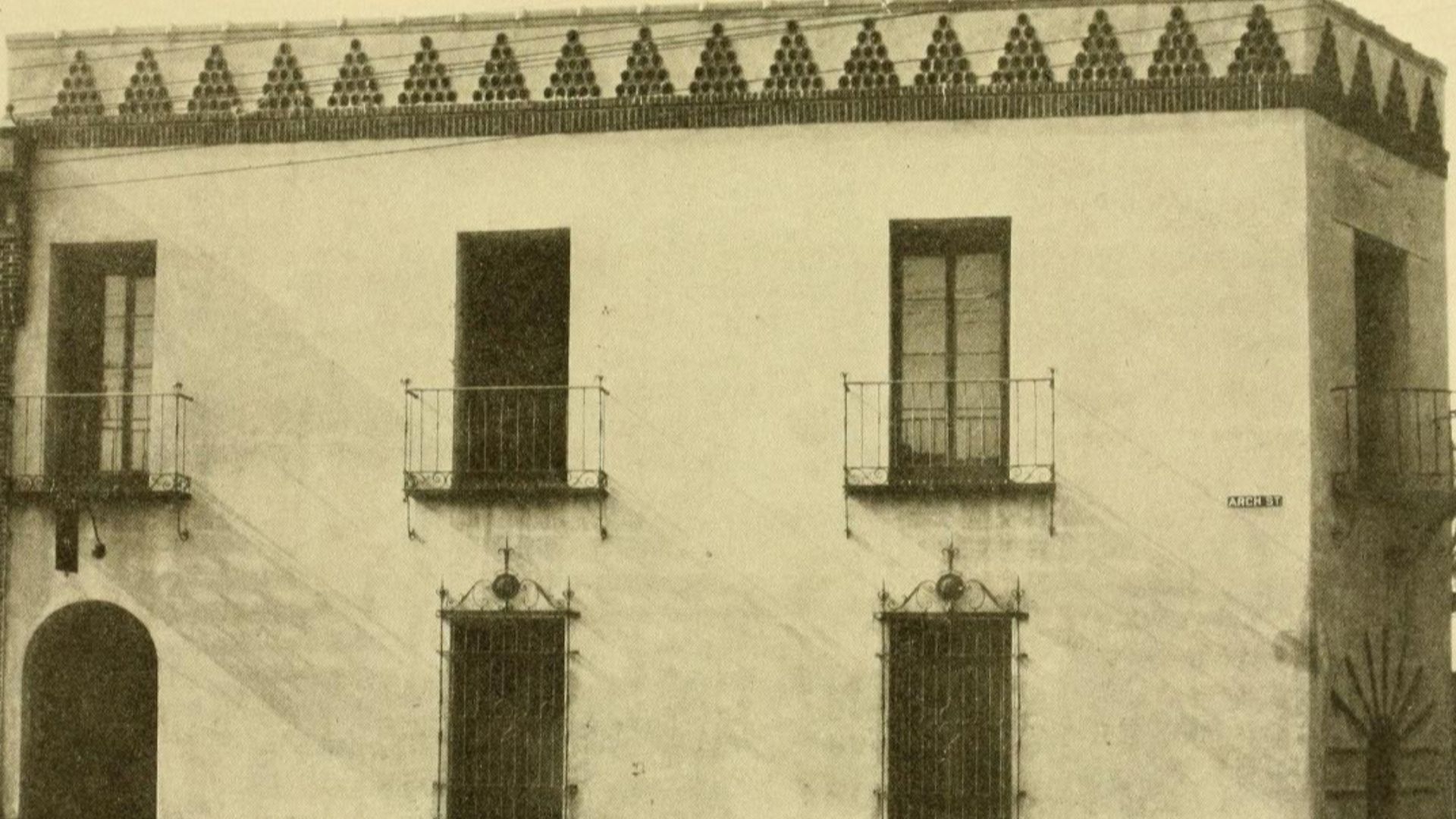

Samuel Yellin Biography

Born in Russian Poland in 1884, Samuel Yellin arrived in Philadelphia at age 21 after apprenticing to a master ironsmith. He studied at the Pennsylvania Museum School of Industrial Art, absorbing principles of medieval metalwork while developing extraordinary technical mastery. By 1915, he established his legendary Arch Street workshop.

Mellor, Meigs & Howe, architects, Wikimedia Commons

Mellor, Meigs & Howe, architects, Wikimedia Commons

Workshop Methods

Yellin's workshop hummed with coal forges, power hammers, and skilled smiths executing designs Yellin sketched himself. He insisted on hand-forging rather than casting, heating iron to 2,300 degrees, hammering while it was cherry-red, and joining pieces through traditional forge-welding.

Entrance Gates

The estate's entry gates showcase Yellin's genius—iron bars twisted into spirals, leaves hand-forged with individual vein patterns, decorative scrollwork that appears effortlessly elegant yet required hours of precise hammer work. Unlike industrial ironwork with its mechanical uniformity, every element shows the smith's hand.

Carptrash (talk), Wikimedia Commons

Carptrash (talk), Wikimedia Commons

Exterior Railings

Railings descended the entrance steps with muscular presence, their posts anchored deep into stone foundations. Yellin designed them specifically for this site, considering the schist walls' texture, the roof's pitch, and the overall composition. He believed ironwork should appear structurally necessary.

Francis Helminski, Wikimedia Commons

Francis Helminski, Wikimedia Commons

Interior Fixtures

Inside, Yellin's ironwork continued the exterior's artistic conversation. There were fireplace screens with medieval motifs, door hinges shaped like leaves and vines, lighting fixtures combining iron with amber glass, and staircase railings flowing upward with botanical elegance. Each piece balanced functionality with artistry.

Kit from Pittsburgh, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Kit from Pittsburgh, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Decorative Hardware

Door handles, window latches, cabinet pulls, keyhole escutcheons—Yellin considered even these smallest details worthy of artistic attention. He designed custom hardware for each room, matching the space's character and function. A library received scholarly Gothic motifs, while kitchen pieces showed rustic simplicity.

BoringHistoryGuy, Wikimedia Commons

BoringHistoryGuy, Wikimedia Commons

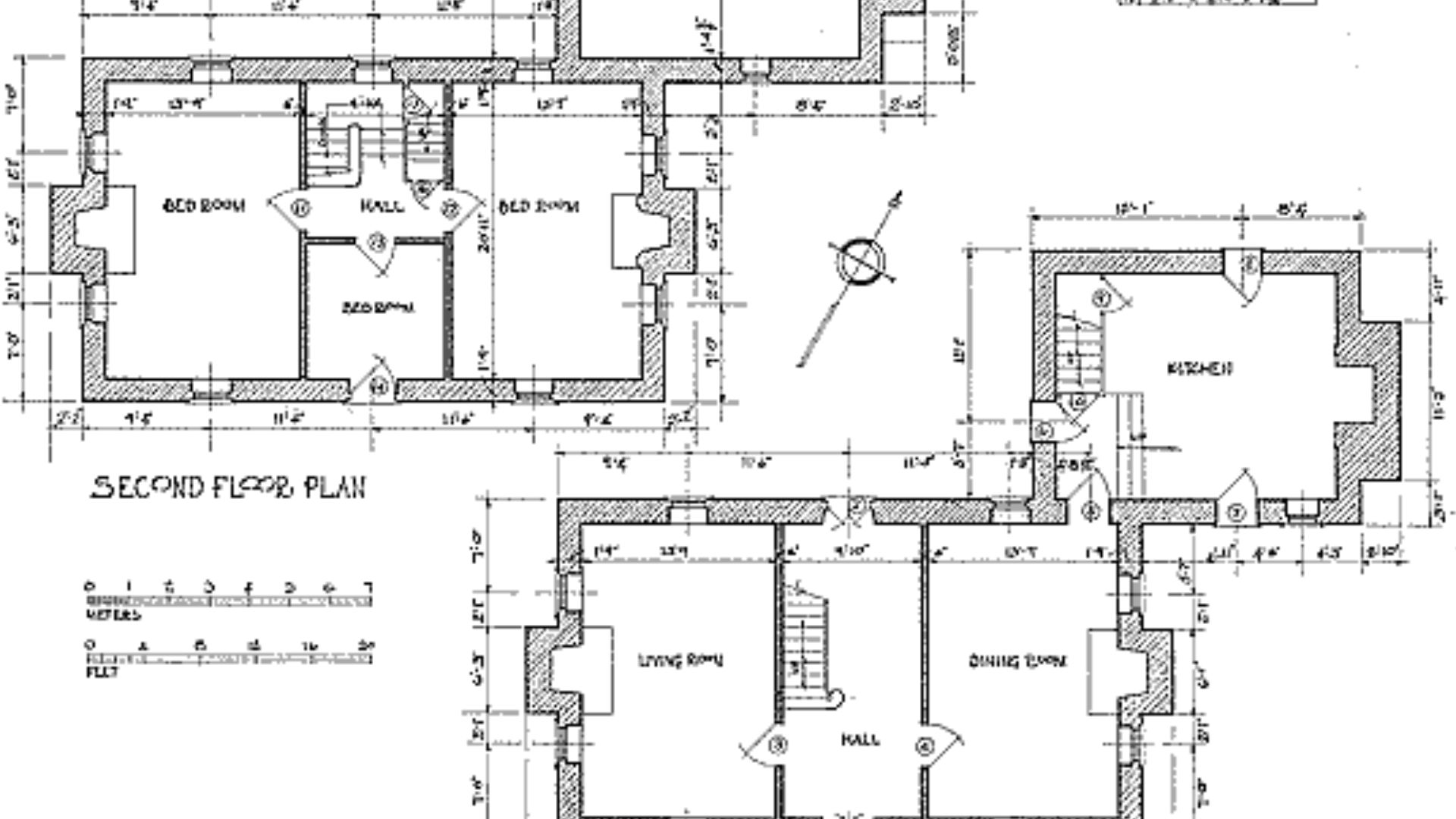

Floor Plan

Normandy exteriors traditionally wrapped around surprisingly modern American floor plans. The estate's layout balanced formal entertaining spaces grand entrance hall, drawing room, and dining room facing the gardens, with comfortable family zones, including a breakfast room, library, and sun porch.

Flack (Lt), No 5 Army Film & Photographic Unit, Wikimedia Commons

Flack (Lt), No 5 Army Film & Photographic Unit, Wikimedia Commons

Principal Rooms

Enter the great hall, and overhead beams of rough-hewn oak immediately establish a medieval atmosphere. The drawing room featured a massive stone fireplace with Yellin's wrought iron fire screen, leaded glass windows casting colored light across plaster walls. Dining room wainscoting rose several feet high.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Period Finishes

Authenticity extended beyond visible surfaces into finishing techniques. Plasterers hand-troweled walls with uneven textures mimicking centuries-old French construction. Oak floors were hand-scraped and pegged rather than nailed. Ceiling beams showed adze marks from manual shaping. Paint colors came from historical pigments.

Original Furnishings

Wealthy families in 1919 furnished estates through European buying trips and Philadelphia's finest dealers. They sought authentic French provincial pieces—armoires, refectory tables, Louis XVI chairs—mixing genuine antiques with quality reproductions. Oriental rugs covered stone and wood floors. Heavy draperies controlled light and drafts.

Jean Henri Riesener, Wikimedia Commons

Jean Henri Riesener, Wikimedia Commons