Puzzles Gaining New Pieces

What if the Exodus story has been holding onto more truth than anyone guessed? Fresh digs across the region are surfacing clues that nudge the ancient account out of legend and into possibility.

A Story Begins With Manetho

Manetho gives you an early clue for rethinking the Exodus story. He describes a marginalized group led by a priest named Osarseph rising against Pharaoh Amenophis, pushing against Egypt’s religious rules, teaming up with Hyksos allies, and eventually being forced out.

Mariette, 1863, Wikimedia Commons

Mariette, 1863, Wikimedia Commons

Josephus Extends The Thread

Josephus later revisits this story and adds a bold detail: he asserts that Osarseph eventually took the name Moses. His version folds the Egyptian account into a broader narrative tradition by identifying the rebel priest as a figure of long-standing significance.

the Providence Lithograph Company, Wikimedia Commons

the Providence Lithograph Company, Wikimedia Commons

Outside Help Enters The Picture

Manetho also records that Osarseph’s followers received assistance from the Hyksos. Their involvement shows how political unrest in Egypt could draw in groups with their own agendas and widen a local conflict into something larger and harder for the state to contain.

British Museum, Wikimedia Commons

British Museum, Wikimedia Commons

Religion Becomes A Flashpoint

According to Manetho, the revolt included actions targeting sacred spaces. Violating those areas would have struck directly at Egyptian identity, which turned a political challenge into something the state saw as a threat to the order that shaped everyday life.

A Shared Fear Surfaces

Thomas Romer points out how Pharaoh’s worry in Exodus 1:10—fearing an internal group joining outside forces—lines up neatly with Manetho’s version. Both traditions carry the same kind of anxiety: people inside Egypt forming dangerous ties beyond its borders.

Nicolas Kovarik / European Union, 2023 / EC - Audiovisual Service, Wikimedia Commons

Nicolas Kovarik / European Union, 2023 / EC - Audiovisual Service, Wikimedia Commons

Pressure Builds Around Amenophis

In Manetho’s telling, Amenophis presides over a kingdom under pressure. Foreign ties and pockets of resistance define the moment, and his struggle mirrors the Biblical picture of Egyptian authority trying to contain a community determined to move toward something different.

Olaf Tausch, Wikimedia Commons

Olaf Tausch, Wikimedia Commons

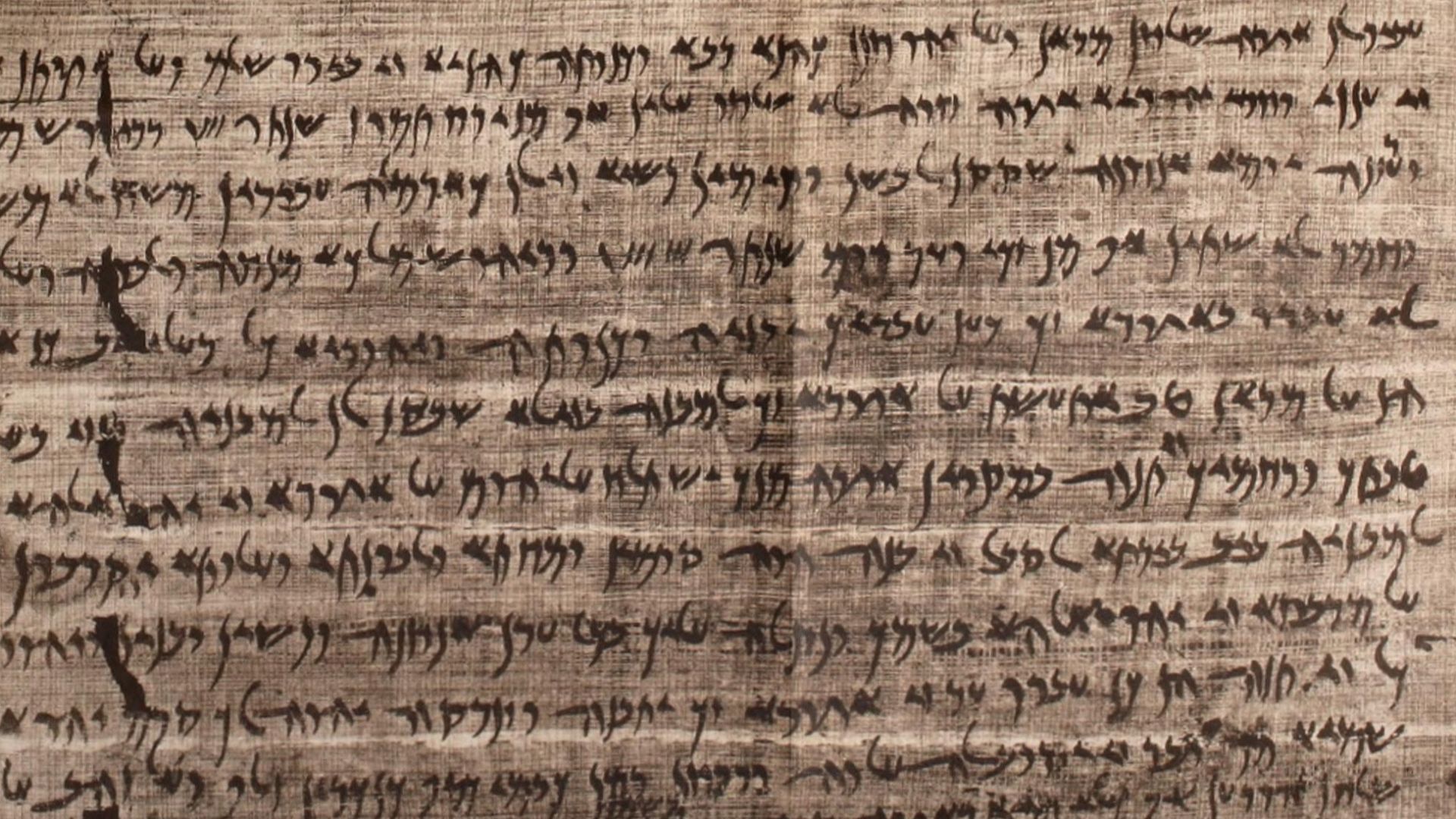

Another Text Records Upheaval

A similar mood appears in the Great Harris Papyrus, which looks back on chaos after Queen Tausert’s passing. It names a figure called Kharu—an irsu who rose to power, dismissed Egypt’s gods, and unsettled the kingdom. The atmosphere lines up with other stories of tension and unexpected challenges.

Tim Evanson from Cleveland Heights, Ohio, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Tim Evanson from Cleveland Heights, Ohio, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Foreign Backing Reappears

The account expands the scope of the unrest by noting Haru’s ties to foreign supporters. Their involvement pushed the conflict beyond a local dispute and turned it into something larger, the kind of situation where every new ally added another layer of difficulty for Egypt.

Jim Padgett, Wikimedia Commons

Jim Padgett, Wikimedia Commons

A King Steps In To End The Crisis

The papyrus credits Setnakhte with breaking Haru’s hold and expelling his followers. You can almost feel the tension ease as the story closes. Instead of an ongoing battle, the scene shifts to a kingdom trying to steady itself and rebuild its center of power.

Karl Richard Lepsius (1810-84), Wikimedia Commons

Karl Richard Lepsius (1810-84), Wikimedia Commons

Imagery Of Flight Takes Shape

A monument attributed to Setnakhte describes enemies fleeing like swallows escaping a hawk. The image focuses on the speed and fear that define the final moments of a collapsing rebellion. It also captures the atmosphere of people abandoning their positions under pressure.

David Roberts, Wikimedia Commons

David Roberts, Wikimedia Commons

Style Links The Stories

The poetic style on the monument—lean, visual, filled with motion—sits comfortably beside the storytelling energy found in the Exodus account. They rely on striking images to capture the turning point when a crisis reaches its breaking point.

A Pattern Starts To Stand Out

Across these Egyptian accounts, you keep seeing the same themes: revolt, foreign alliances, religious conflict, and abrupt departures. Although none of the stories match Exodus exactly, together they form a cluster scholars use to understand how different memories might sit in the same historical neighborhood.

Another Sudden Escape Pattern Appears

You see this theme again when Setnakhte’s enemies flee so quickly that they leave valuables behind. Exodus flips the moment, showing Egyptians giving valuables away instead, but both accounts lean on the same idea: departures shaped by pressure, fear, and little time to prepare.

the Providence Lithograph Company, Wikimedia Commons

the Providence Lithograph Company, Wikimedia Commons

A Smaller Group Enters The Spotlight

Richard Elliott Friedman shifts the conversation by suggesting the Exodus memory may have started with the Levites alone. Several of them carried Egyptian names and customs, which hints that their upbringing had real contact with Egypt rather than distant cultural influence.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Names That Point Back To Egypt

Names such as Phinehas and Hophni pull the picture into focus. Those names point toward real touchpoints with Egyptian culture and help explain why the Levites may have brought unique memories into early Israel’s story and complete the line of connections running across all the sources above.

Customs That Stayed With Them

Circumcision appears most prominently in texts linked to the Levites, pointing to a practice they seem to have carried from their time in Egypt, well before it spread through Israel. That kind of ritual continuity supports the view that the Levites were the ones who actually lived there.

Levite Distinctiveness Highlighted

Levite practices differ from non-Levite traditions in ways linked to Egyptian experience. These variations support interpretations that see them as the primary carriers of Exodus memory, later broadening that memory into a story shared by all tribes.

Jim Padgett, Wikimedia Commons

Jim Padgett, Wikimedia Commons

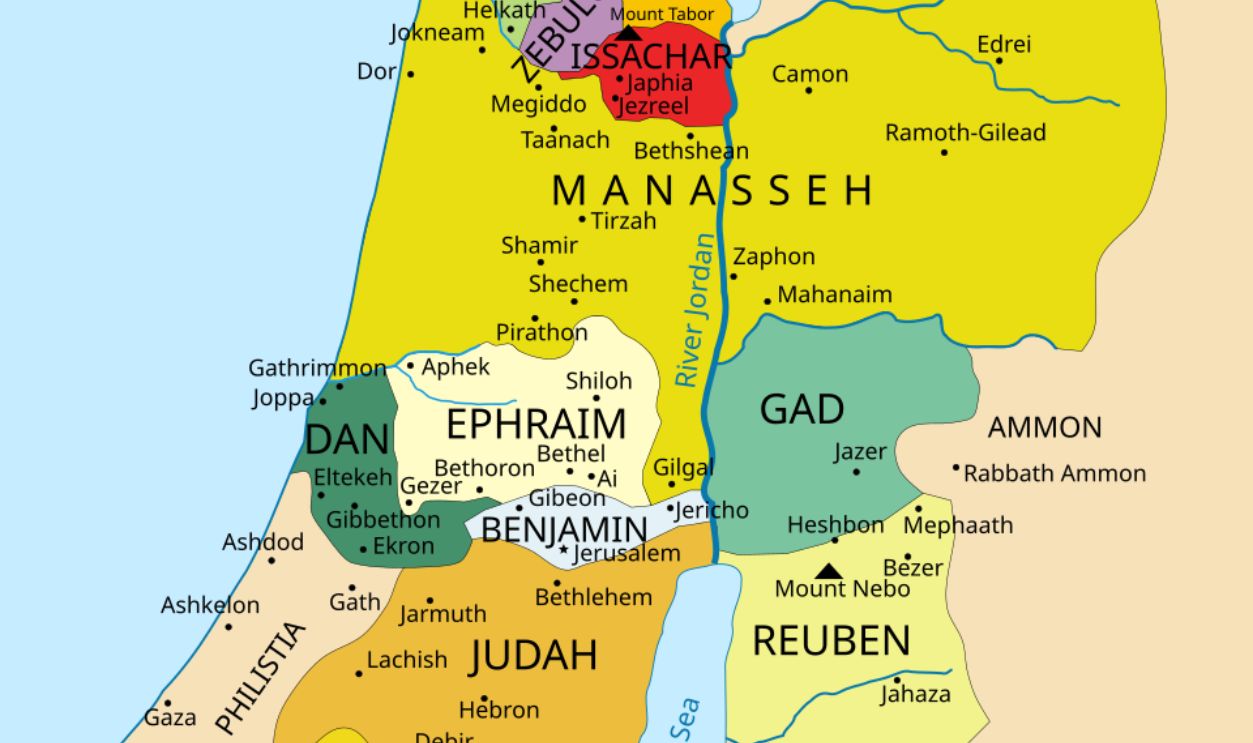

A Migration That Wasn’t National

One idea shifts the scale of the story: if only the Levites had left Egypt, the Exodus becomes a focused migration rather than a full-tribal departure. A small group entering Canaan with sharp memories could later share those stories with communities still shaping their identity.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Early Poetry Hints At Who Was There

Miriam’s song gives you a clue about who actually experienced Egypt. It celebrates escape without reaching for every tribe, which fits a world where only one group carries firsthand memories. Early poetry tends to reveal who lived through an event before tradition widens the lens.

Vandal B~commonswiki, Wikimedia Commons

Vandal B~commonswiki, Wikimedia Commons

A Silence That Speaks Volumes

Deborah’s song shifts the scene entirely. It names tribes fighting in Canaan yet never mentions the Levites, and that silence matters. Paired with Miriam’s perspective, it suggests the Levites hadn’t wholly joined Israel’s tribal network at that point.

Johanna Unger, Wikimedia Commons

Johanna Unger, Wikimedia Commons

Two Poems, Two Histories

Reading the songs side by side highlights a clear mismatch. One remembers leaving Egypt; the other describes conflict in Canaan without the Levites in sight. That contrast supports the idea of staggered arrivals—different groups entering the story at different times.

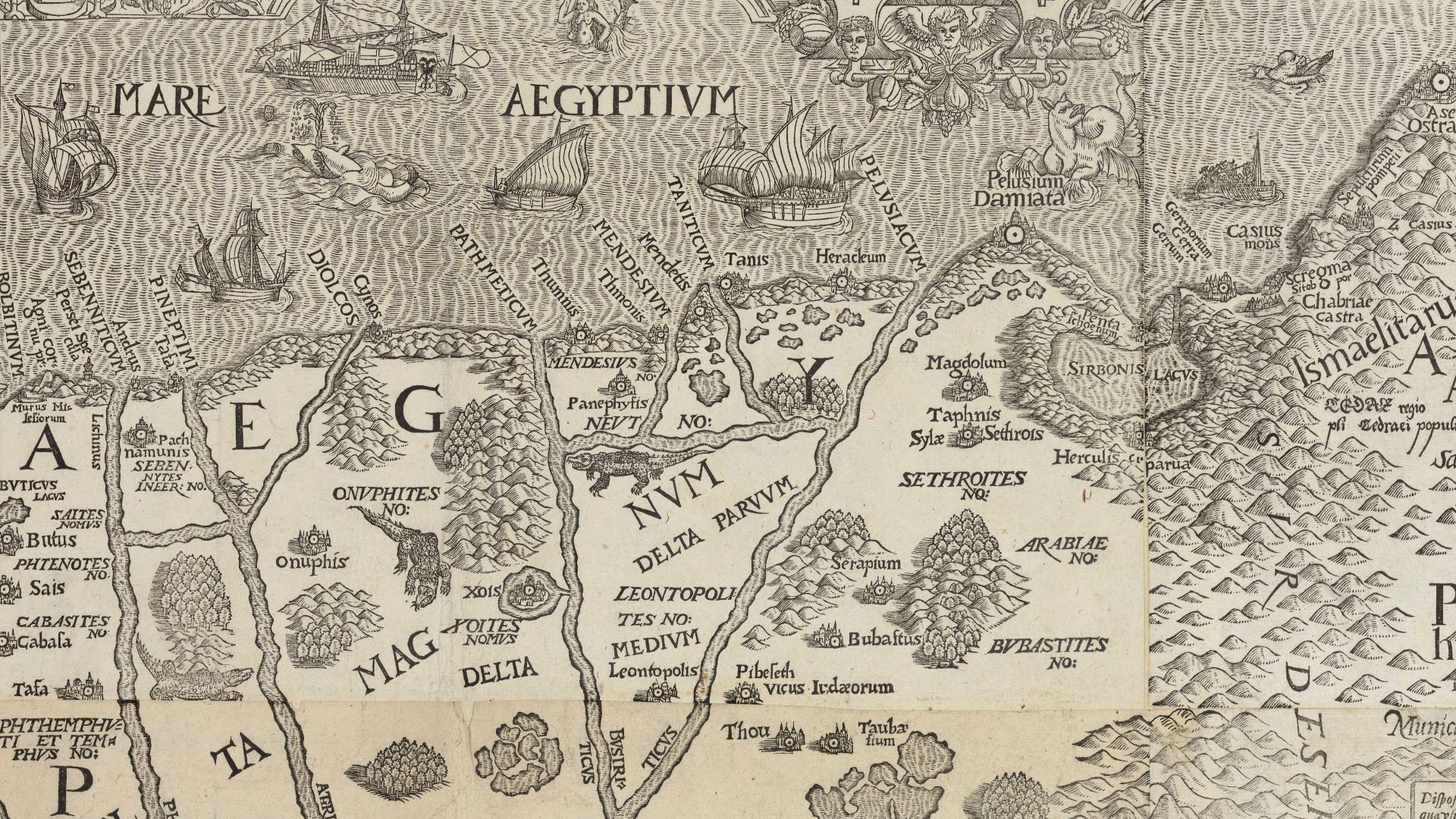

http://maps.bpl.org, Wikimedia Commons

http://maps.bpl.org, Wikimedia Commons

Memory Gaps That Reveal The Past

Those differences become small windows into how Israel’s tradition grew. The poems show uneven memories across communities, helping you trace when the Levites may have joined the wider group. Sometimes the moments left unspoken reveal more than the lines that remain.

Philip De Vere, Wikimedia Commons

Philip De Vere, Wikimedia Commons

Egyptian Influence In Levite Writing

Leviticus-linked material carries the pattern forward. Egyptian features show up more strongly there than in other books, which hints that the writers brought their own memories into ritual law rather than relying solely on shared Israelite practice.

Tracing Who Brought What

Other texts skip those Egyptian elements entirely, suggesting only part of Israel carried customs from outside Canaan. When you see those influences appear unevenly, it becomes easier to trace which group introduced specific practices into the developing tradition.

Egyptian Marks That Stayed Behind

You see the thread continue in the way architecture and naming patterns carry Egyptian hints into Levitic writings. Those details show how long cultural memory can last and help link the Levites’s earlier world to the stories they later passed into Israel’s tradition.

Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons

Diego Delso, Wikimedia Commons

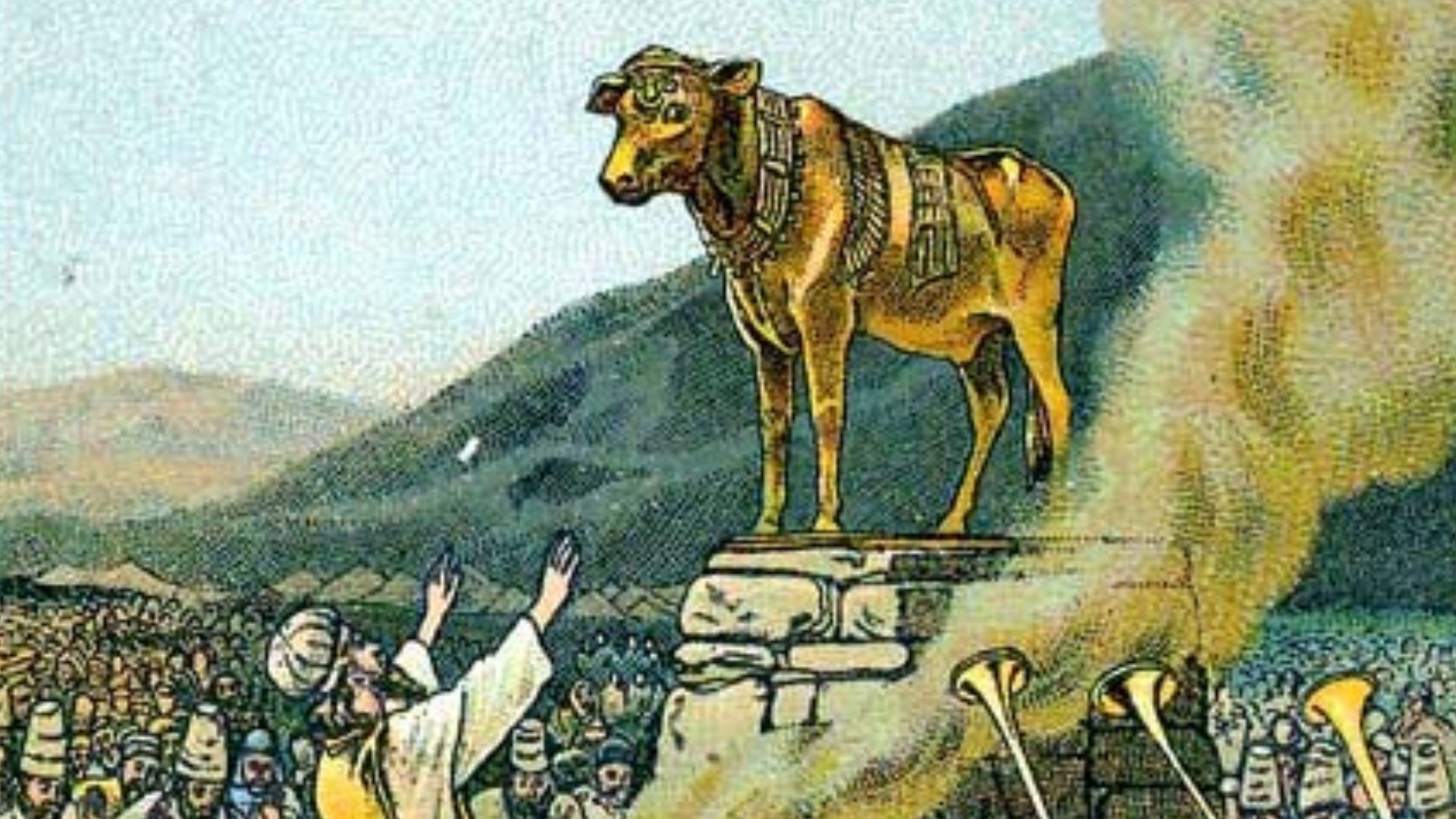

A New Form Of Worship Enters Israel

The picture shifts once the Levites join the wider tribes. They bring Yahweh worship with them, and that tradition meets Israel’s existing devotion to El. Together, the two streams begin shaping a shared religious identity built through gradual blending rather than replacement.

Nathaniel Ritmeyer, Wikimedia Commons

Nathaniel Ritmeyer, Wikimedia Commons

Two Deities Become One

Instead of keeping El and Yahweh separate, the Israelites eventually identify them as the same god. Levite-written passages like Exodus 3:15 and 6:2–3 reflect this merger, which becomes one of the earliest steps toward the monotheistic system later associated with Israel.

Theology Through Migration

The merging of Yahweh and El demonstrates how migration reshapes belief. Levite arrival introduced concepts that blended with local worship. This blending formed a religious identity that would later define Israel as centered on one unified deity.

the Providence Lithograph Company, Wikimedia Commons

the Providence Lithograph Company, Wikimedia Commons

A Merger That Changed Everything

That blending of El and Yahweh marks a turning point. When Levite memory met tribal tradition, the result was a unified view of God that neither group held alone. Without that merger, Israel’s theological development might have moved in a very different direction.

Eickenberg at en.wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

Eickenberg at en.wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons

Beliefs Shift As People Move

The effects become even clearer when you look at how worship changed over time. If the Levites arrived from Egypt, they brought ideas that the tribes eventually accepted. The result isn’t a sudden overhaul but a slow convergence—two traditions growing toward one shared faith.

publishers of the 1890 Holman Bible, Wikimedia Commons

publishers of the 1890 Holman Bible, Wikimedia Commons

Memory That Lives Inside Theology

This merging reveals how cultural memory works. Two communities gradually align, and Levite experience folds into the wider tradition. Their background becomes one of the strands shaping how Israel comes to understand the divine.

Henri Felix Emmanuel Philippoteaux, Wikimedia Commons

Henri Felix Emmanuel Philippoteaux, Wikimedia Commons

A Shift Toward One God Begins

Israel’s move toward monotheism makes more sense once the Levites enter the picture. Their background brought ideas that nudged belief in a new direction. The merging of El and Yahweh didn’t arrive late—it acted as an early spark that reshaped Israel’s religious story.

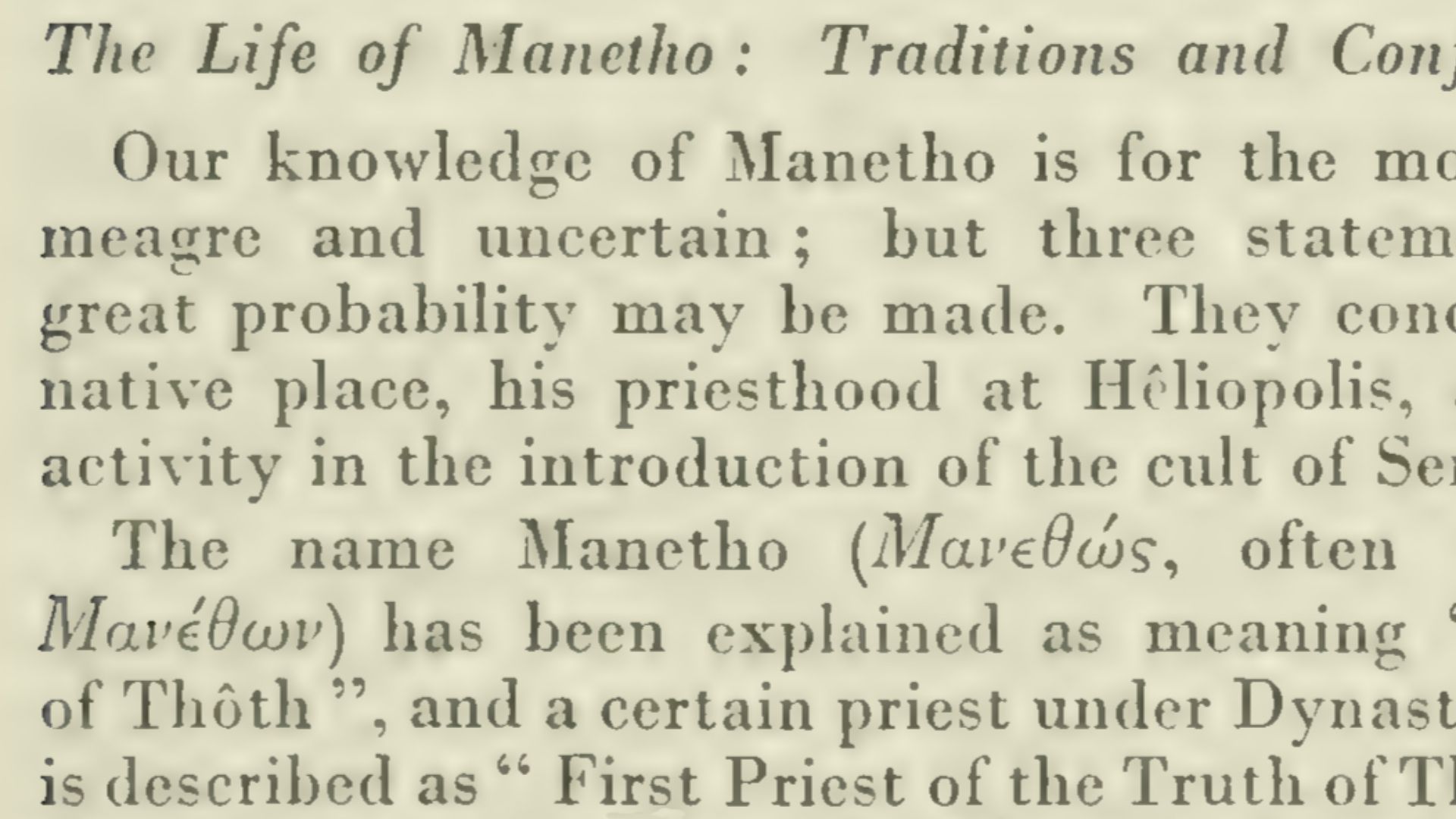

Egyptian Stories Sit In The Same Scene

When you step back, Egyptian texts describe a world that feels emotionally close to the Exodus setting. Manetho, the Harris Papyrus, and the Elephantine monument all recall foreign groups, upheaval, and sudden departures. They don’t copy Israel’s story, but they echo its atmosphere.

Waddell, W. G. (William Gillan), 1884-1945, Wikimedia Commons

Waddell, W. G. (William Gillan), 1884-1945, Wikimedia Commons

Familiar Story Shapes Reappear

Those Egyptian accounts also return to patterns you see in Biblical writing: internal struggle, outside support, and moments when authority loses its grip. Watching these shapes repeat across traditions helps scholars track how stories survive and shift without tying them to strict historical matches.

Thomas de Keyser, Wikimedia Commons

Thomas de Keyser, Wikimedia Commons

Evidence Works As A Cluster

It’s emphasized that no single object proves the Exodus. What matters instead is how certain themes gather across sources. When the same kinds of clues keep showing up, the value lies in the pattern rather than in a single, decisive find.

Bernard Trebacz (1869-1941), Wikimedia Commons

Bernard Trebacz (1869-1941), Wikimedia Commons

A Wider Picture Emerges From Fragments

Place pieces from Egypt, Israel, and early poetry together, and you don’t get a straight timeline—you get a mosaic. Each fragment holds a small part of the story. When read side by side, they create a deeper scene for understanding how the Exodus memory formed.

Son of Groucho from Scotland, Wikimedia Commons

Son of Groucho from Scotland, Wikimedia Commons

How A People Builds Its Story

The Exodus tradition works on two levels: it remembers early events and shapes identity. When Egyptian parallels join the conversation, scholars get fresh ways to see how communities describe hardship, departure, and purpose—moments that later define who they understand themselves to be.

School of Rembrandt, Wikimedia Commons

School of Rembrandt, Wikimedia Commons

Blended Cultures Form A Shared Memory

Evidence from names, customs, and theology points to a mix of Levite migrants and local tribes. That blending helps explain why the Exodus story eventually became a national narrative and not a narrow memory held by one group.

Architecture Remembers Too

The similarity between the Tabernacle and Rameses II’s field tent keeps the Egyptian thread alive. Those shared design cues place Israel’s sacred space inside a broader Egyptian-influenced world, giving the tradition more historical depth than a simple origin story might suggest.

Songs That Mark Different Eras

The Songs of Miriam and Deborah show two snapshots of Israel at very different stages. Their mismatched references point to communities joining the coalition over time, and those differences help scholars trace when certain groups—including the Levites—became part of the larger story.

12 tribus de Israel.svg: Translated by Kordas, Wikimedia Commons

12 tribus de Israel.svg: Translated by Kordas, Wikimedia Commons

Rise And Recovery As A Shared Rhythm

Egyptian texts like the Harris Papyrus and Elephantine inscriptions describe moments of collapse followed by restoration. Exodus follows a similar rhythm. The motifs appear across cultures, but their repetition doesn’t require shared origins—just shared experiences of instability and renewal.

Letter by Yedoniah; Photographer unknown, Wikimedia Commons

Letter by Yedoniah; Photographer unknown, Wikimedia Commons

A Fear That Keeps Returning

Both Exodus and Manetho highlight a Pharaoh worried about internal groups forming outside alliances. It’s a pattern you see whenever kingdoms face uncertainty: questions of loyalty become urgent, and leaders fear the pressure of ties beyond their control.

ArchaiOptix, Wikimedia Commons

ArchaiOptix, Wikimedia Commons

Familiar Leaders In Troubled Times

Figures like Haru and Osarseph appear in Egyptian records as foreign-backed challengers to royal authority. Their stories fit a recognizable pattern of uprisings that echo the tension in Exodus, offering context for how the Biblical narrative frames its central struggle.

Where Story And History Meet

You see the lines blur once you compare Egyptian inscriptions with Biblical stories. Both preserve partial memories of turbulent times, each shaped by the lens of its own community. When the fragments sit side by side, you start to notice how narrative becomes a tool for making sense of upheaval and divine involvement.