Meet The Anasazi

The Anasazi, also the Ancestral Puebloans, were the ancestors of today’s Pueblo peoples of the American Southwest. The term “Anasazi” comes from a Navajo word meaning “ancient enemies” or “ancient outsiders”. They were doing so well, then….they supposedly vanished.

Who Are The Anasazi

The Anasazi resided in the Four Corners region, where the states of Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico meet. Their culture flourished from around 200 BCE to 1300 CE, with significant developments during the Basketmaker and Pueblo periods. Today, they are survived by modern Pueblo peoples, including the Hopi and Zuni.

Steve Shook, Wikimedia Commons

Steve Shook, Wikimedia Commons

Their Early Life Was Quite Simple

Early Ancestral Puebloans were hunters and gatherers. They lived in pithouses and moved seasonally. Daily life centered on survival and adapting to the arid land—long before pottery or complex rituals emerged. Here is how all that unfolded.

Thomas C. Gray, Wikimedia Commons

Thomas C. Gray, Wikimedia Commons

Their Move From Nomads To Farmers

Around 100 BCE, communities transitioned from a nomadic lifestyle to one of planting crops. The families would tend cornfields while weaving tightly woven baskets for storage. These farmers began settling in small clusters, laying the foundations of the Ancestral Puebloan civilization that would shape the region for centuries.

Their Crops Were Corn, Beans, And Squash

Called the “Three Sisters,” maize, beans, and squash were essential for survival. Corn-dominated diets provided the majority of the calories they needed. Beans added protein, squash offered vitamins, and together the waste enriched the soil as manure.

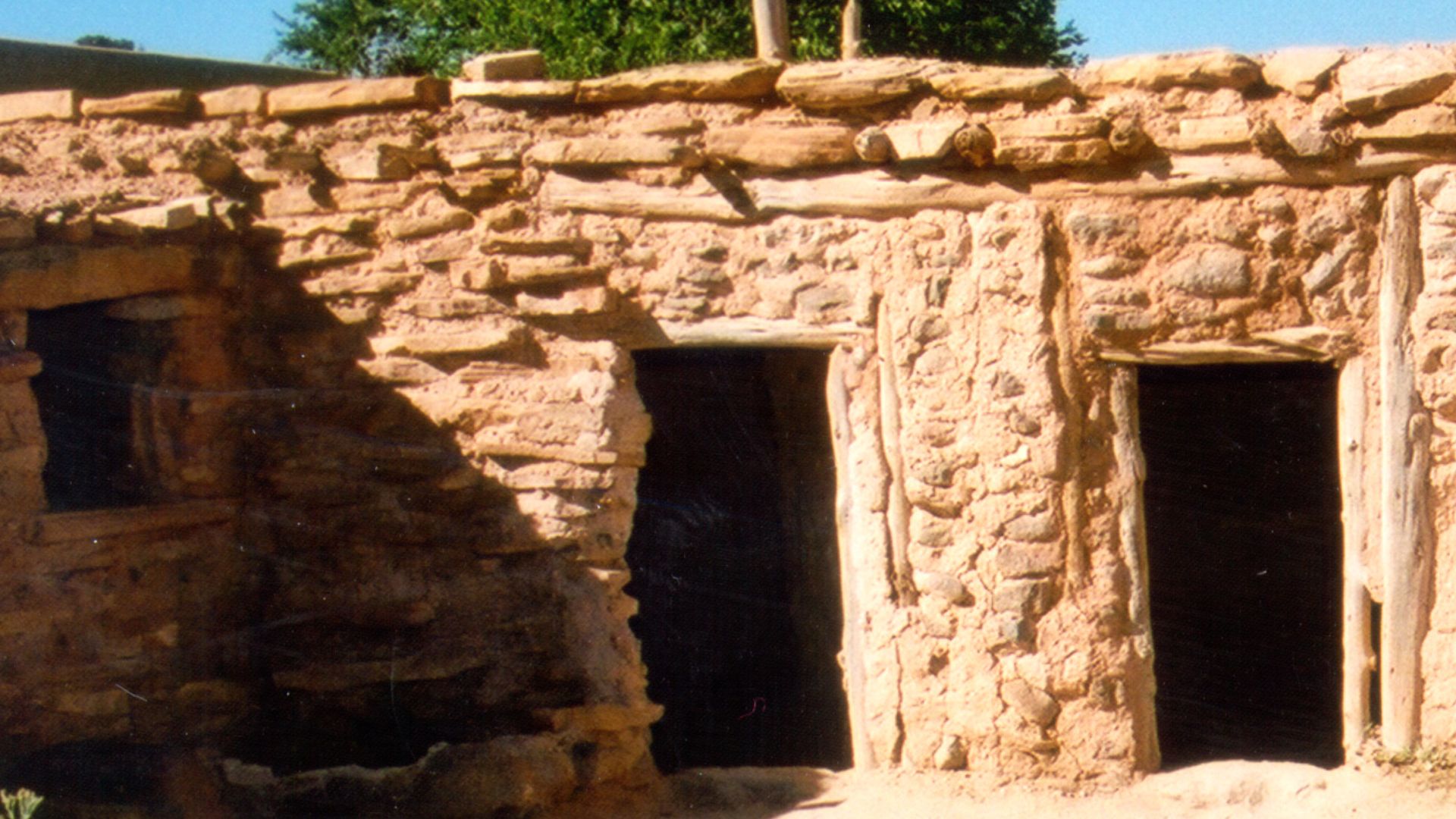

They Began Building Above Ground

Early families dug shallow pits, covering them with timber and adobe. Entry came through the roof ladders to create a cool shelter in summer and warmth in winter. Later, archaeologists discovered household items left behind, and they included bone awls and stone scrapers, all preserved in the earth for centuries.

James Q. Jacobs, Wikimedia Commons

James Q. Jacobs, Wikimedia Commons

Their Clay Vessels Changed Daily Life

Over time, pottery began to replace baskets as cooking and storage vessels. Coiled clay pots with black-on-white designs were both functional and artistic. With pottery also came new foods: stews, boiled corn, boiled beans, and preserved seeds. The result? A more diversified diet that strengthens long-term food security.

Ken Lund from Reno, Nevada, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Ken Lund from Reno, Nevada, USA, Wikimedia Commons

Farming In The Harsh Desert Southwest Wasn’t Easy

To grow corn in the desert, one needed mastery of water. The Anasazi had to think quickly, and they devised carved check dams to manage the water. Additionally, they built canals and created reservoirs to catch seasonal rain. These networks supported entire villages, and they transformed arid land into green patches.

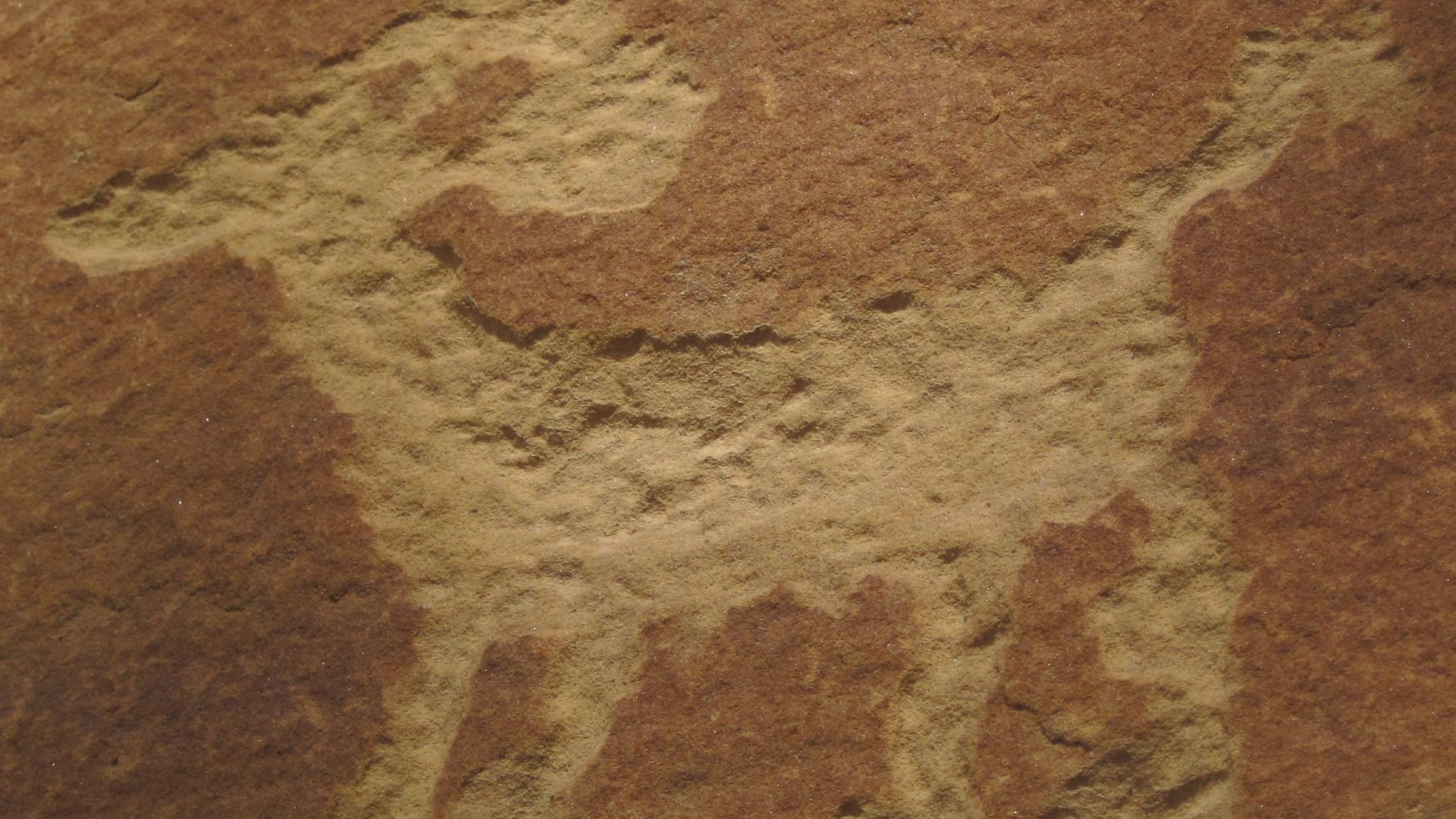

Basketmakers Also Made Rock Art

On canyon walls, hunters would carve graffiti—art and messages—in the form of spirals, animals, and figures. Some aligned with solar events, such as equinoxes. These may have been used to guide generations on planting cycles or tell of generational stories.

James St. John, Wikimedia Commons

James St. John, Wikimedia Commons

In The Transition To Pueblo I, The Villages Grow Larger And More Complex

By 750 CE, small clusters merged into larger pueblos. Communities built larger rectangular rooms above ground from stone and adobe. Dozens of families shared walls and worked side by side. These developments created stronger ties and marked the rise of towns.

The Rise Of Multi-Room Houses

The growing population needed new houses. And so, the people took an architectural leap by building multi-room compounds. Using sandstone blocks cemented with mud, people built structures two stories high. These complexes were so sophisticated that others had plazas and courtyards, where children played and elders taught traditions.

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

They Also Built Kivas, Sacred Spaces Underground

Kivas—circular, underground ceremonial chambers—emerged as cultural centers. Entered through ladders, they featured fire pits and sipapus, symbolic portals to the spirit world. Everything administrative and religious unfolded here. To date, the kiva remains one of the most recognizable and enduring Puebloan legacies.

Trade Was Booming

The Anasazi traded across vast networks—from Mesoamerica to the Pacific. They acquired macaws, seashells, turquoise, and copper via intermediaries and regional allies like the Hohokam. Chaco Canyon facilitated this exchange, transforming exotic goods into cultural capital and connecting desert communities to distant civilizations through commerce.

Pueblo II: The Dawn Of Monumental Construction

Around 900 CE, something shifted. Stone masonry improved, and the multi-storied dwellings we just spoke about spread further across the land. This was no longer a scattering of villages—it was the era of monumental public works that hinted at an expanding social and spiritual order.

More Context On What Pueblo Means

Before we proceed, here is context on the term “Pueblo”. The names Pueblo I and Pueblo II originate from the Pecos Classification System, a chronological framework that archaeologists use to organize the cultural evolution of the Ancestral Puebloans. These labels mark distinct periods of everything from technological to social development.

Chaco Canyon Emerges As A Cultural Powerhouse

Among the Pueblo II structures was the Chaco Canyon, which became the beating heart of the Anasazi world. Great houses like Pueblo Bonito held hundreds of rooms. Roads radiated outward in straight lines across the desert. Think of it as a hub of ceremony and astronomy. Even centralized power.

Pueblo Bonito Was A Stone City Of 600 Rooms

Pueblo Bonito wasn’t just large—it was extraordinary. Four stories high, shaped like a giant “D,” it contained plazas, kivas, courtyards, and storerooms. With 600 rooms, it stood as the largest building in North America until the 19th century. What came next raised more eyebrows.

Highways Linking The Ancient Southwest

Straight as arrows, massive roads up to 30 feet wide cut through mesas— elevated flat-topped landforms that served as prime real estate for early settlements and deserts. Some stretched 60 miles without deviation. These trails were engineered thoroughfares connecting distant settlements. But why build such effort-demanding paths?

Infrogmation of New Orleans, Wikimedia Commons

Infrogmation of New Orleans, Wikimedia Commons

Ancient Astronomical Precision

High on Fajada Butte, slabs of stone cast dagger-shaped rays of light onto carved spirals. On solstices and equinoxes, they aligned perfectly. This solar calendar guided planting and ceremonies. Astronomy was engineered into architecture for these people, setting the stage for their marvels.

National Park Service, Wikimedia Commons

National Park Service, Wikimedia Commons

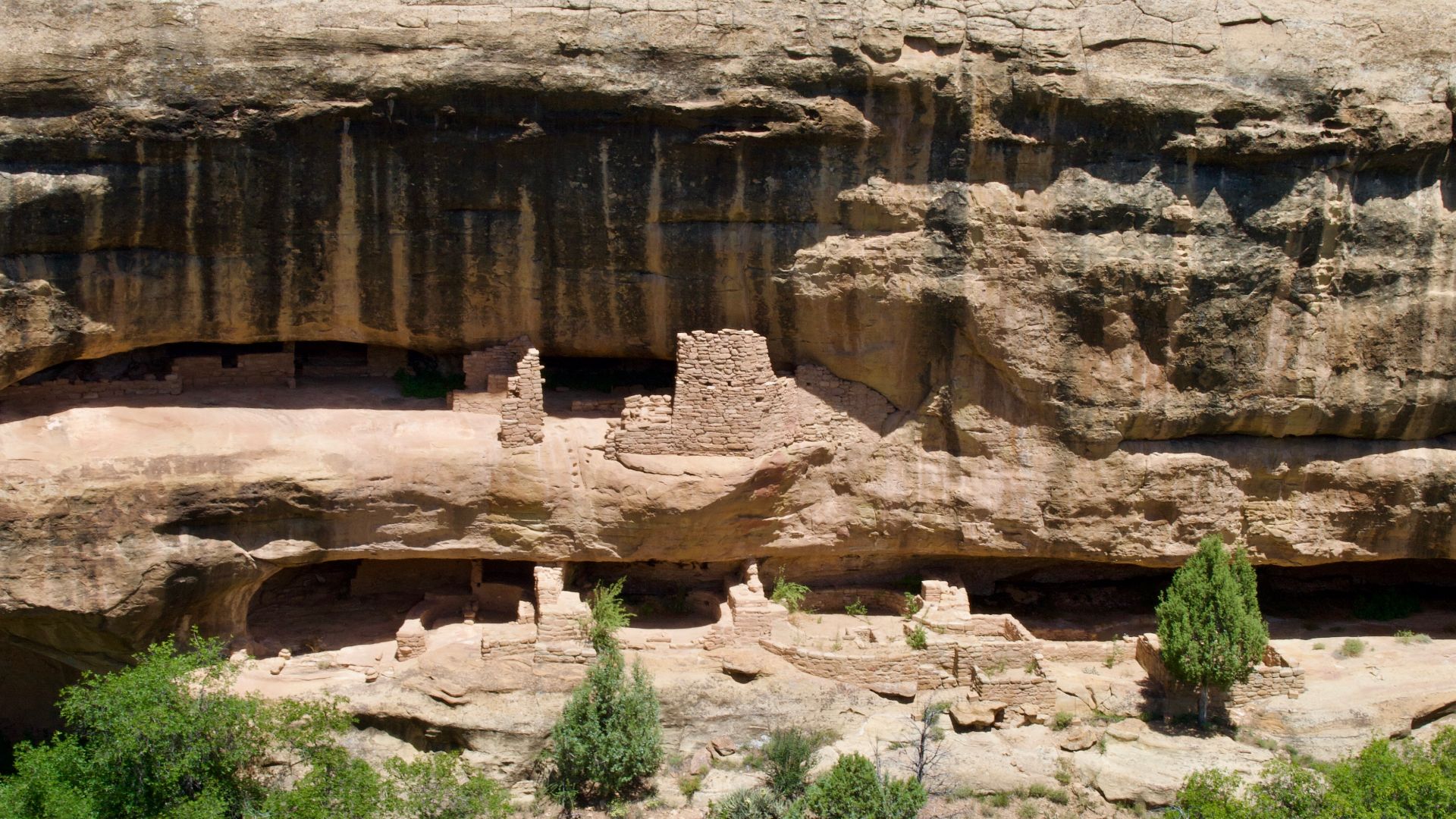

Mesa Verde’s First Cliff Settlements Appear

By 1100 CE, families turned canyon cliffs into homes. They carved dwellings into alcoves, stacked rooms vertically, and used ladders to reach them. These stone villages seemed like fortresses against time, though their real purpose became clearer as threats emerged later. FYI, Mesa Verde means “green table” in Spanish.

Terraces And Reservoirs Got More Advanced

Agriculture also kept advancing. The terraces they built slowed erosion. Then, the reservoirs captured run-off, and check dams maximized water. This adaptation allowed larger populations to thrive. However, survival in such a harsh land always came at a cost, and soon environmental stress began to knock at the door.

Infrogmation of New Orleans, Wikimedia Commons

Infrogmation of New Orleans, Wikimedia Commons

Enter Pueblo III: The Era Of Cliff Palaces

With the sky as the limit, the villages kept climbing even higher into cliffs. Entire palaces with hundreds of rooms, like Cliff Palace at Mesa Verde, towered above canyons. These complexes dazzled in size and sophistication. Yet, the shift to such hard-to-reach sites hinted at something unsettling.

Massimo Catarinella, Wikimedia Commons

Massimo Catarinella, Wikimedia Commons

Tower Kivas And Defensive Fortresses Multiply

Circular kivas rose into towers, and fortresses appeared on canyon rims. Construction choices reveal communities bracing for conflict. Burned timbers and defensive walls suggest more than architectural ambition. This was a society preparing for turbulent times—the storm was coming.

Rationalobserver, Wikimedia Commons

Rationalobserver, Wikimedia Commons

The Signs Of Social Strain Showed

Archaeologists often find sites that were suddenly deserted, only to be reoccupied nearby. Moving so frequently signaled stress. Food shortages or even social fractures may have triggered these shifts. Such patterns suggest that life was becoming increasingly unstable.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

The Great Drought Of 1276–1299 Begins

Then came the turning point. Tree rings show a drought lasting over two decades, one of the worst in recorded prehistory. Crops withered, water vanished, and survival became a desperate struggle. Every community felt the weight of the relentless sun pressing down year after year.

King of Hearts, Wikimedia Commons

King of Hearts, Wikimedia Commons

Scientific Proof Of Drought

Dendrochronology—the science of dating tree rings—reveals the exact years of drought. Rings narrowed dramatically during the late 1200s, confirming a catastrophic environmental event. Farmers couldn’t ignore such prolonged aridity. These rings provide hard proof that the Great Drought was no myth—it carved itself into wood.

English: NPS Photo , Wikimedia Commons

English: NPS Photo , Wikimedia Commons

Deforestation And Soil Depletion Spread

With a growing population, timber use increased significantly for building and firewood. As a result, forests near Chaco Canyon vanished, and this forced people to haul logs over 60 miles. The soil wore thin from overfarming, making it harder to grow crops. Environmental pressure piled on, something communities could not sustain.

AlisonRuthHughes, Wikimedia Commons

AlisonRuthHughes, Wikimedia Commons

Violence Was Also On The Rise

Excavations done much later expose skeletons with skull fractures. Others even had scalping marks. And they also discovered burned dwellings. These point to episodes of violence. Conflict may have erupted as resources began to dwindle. Tensions boiled over, and neighbors who once traded may have turned on each other.

U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, Wikimedia Commons

U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, Wikimedia Commons

Others Took Safety In Sheer Rock Walls

Why climb into cliffs for shelter? Safety. Remote alcoves provided defense against raids. Ladders could be pulled up, and narrow entries could be controlled. These fortresses were survival hideaways. Such drastic measures hint that insecurity dominated everyday life during the late 1200s.

There Were Evidence Of Raids

Some sites reveal massacres—entire families left where they fell. Raids likely came from migrating groups or rival factions competing for dwindling farmland. Fortifications and burned structures serve as chilling reminders of a time when trust eroded and survival meant constant vigilance.

Grand Canyon National Park, Wikimedia Commons

Grand Canyon National Park, Wikimedia Commons

Malnutrition And Disease Leave Their Mark On Skeletons

The bones from this time really tell the story—people stopped growing the way they should, because their skeletons showed holes and signs of anemia. Food was running out, villages were packed and stressed, and once disease hit, weakened bodies just couldn’t fight back.

King of Hearts, Wikimedia Commons

King of Hearts, Wikimedia Commons

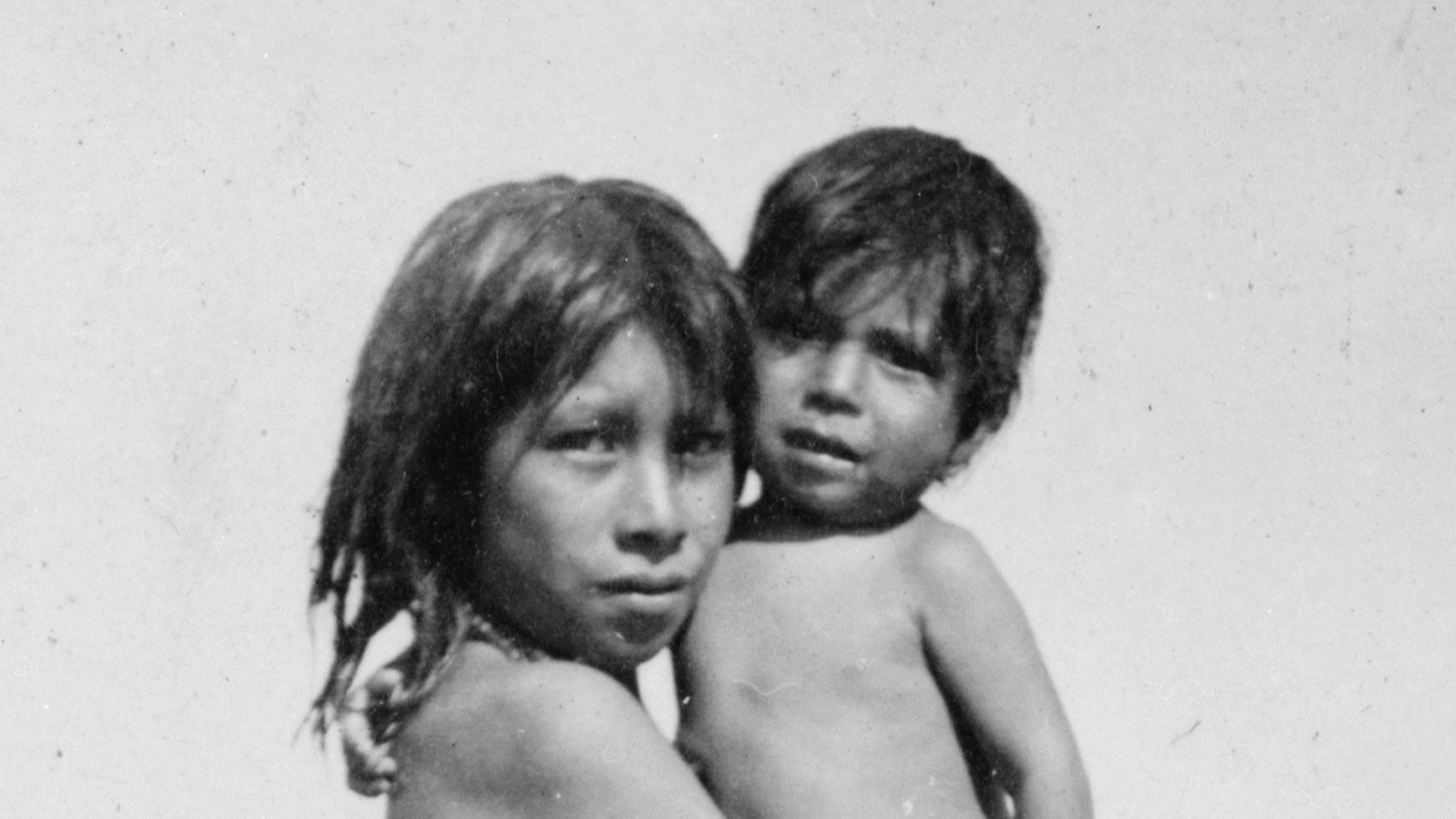

Infant Mortality Surges In The Late 13th Century

Burials say it all. More and more infants and young kids in the late 13th Century didn’t make it. Malnutrition and mothers weakened by drought all added to the toll. And every tiny grave wasn’t just a family’s loss; it was a community slowly coming apart.

Monsen, Frederick, 1865-1929, photographer., Wikimedia Commons

Monsen, Frederick, 1865-1929, photographer., Wikimedia Commons

Religious Shifts

Some great ceremonial towers were abandoned mid-construction. Their sudden halt points to shifting beliefs. Communities may have lost faith in old centers like Chaco, turning toward smaller, more local traditions. These changes mark the first visible steps toward a new cultural direction.

Chaco Canyon’s Influence Fades Into Silence

Once the heart of a vast network, Chaco Canyon fell quiet. Great houses emptied, roads no longer pulsed with travelers. Yet silence here was different because it signaled movement. People carried their traditions to new lands, where they reshaped them.

Settlements Emptied By 1300 CE

By the end of the 13th century, all the cliff palaces and sprawling pueblos stood deserted. But just don’t lose hope because the story didn’t end in ruin. Communities relocated, and they carried with them corn seeds, pottery styles, and spiritual practices to distant valleys. Migration was survival, not collapse.

They Sadly Could Not Carry Everything With Them

Later on, archaeologists uncovered pieces of grinding stones and entire homes that were abandoned as if the people had walked away in haste. However, the descendants tell a different story: items were left intentionally as a symbolic nod to closure. Leaving old places behind like sealed chapters.

Hopi And Zuni Oral Traditions Recall The Journey

Oral histories preserved by Hopi and Zuni recount migrations from the north. These stories recall and retell the whole journey—one guided by spiritual duty and cycles of renewal. Their stories encode geography, seasonal rhythms, and sacred obligations, often aligning with archaeological evidence, such as settlement patterns and ceremonial architecture.

Miscellaneous Items in High Demand, PPOC, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Miscellaneous Items in High Demand, PPOC, Library of Congress, Wikimedia Commons

Migration To The Rio Grande

Evidence shows groups resettling along the Rio Grande. New pueblos rose with familiar designs like the kivas and communal storage. These settlements grew into thriving centers to prove that cultural continuity outweighed the loss of older homelands in the Four Corners.

Andreas F. Borchert, Wikimedia Commons

Andreas F. Borchert, Wikimedia Commons

Pueblo People Today Claim Direct Ancestry To The Anasazi

Modern Pueblo nations, including Hopi, Zuni, and Tewa, proudly trace their heritage to these ancestral builders. Ceremonies, farming techniques, and architectural traditions remain alive and well. Continuity here is a direct link from past to present, unbroken by centuries.

Einar E. Kvaran aka Carptrash (talk), Wikimedia Commons

Einar E. Kvaran aka Carptrash (talk), Wikimedia Commons

Archaeologists Reject The Word “Anasazi” As An Outsider’s Label

The term “Anasazi,” meaning “ancient enemies” in Navajo, misrepresents the identity of the ancient people. Today, “Ancestral Puebloans” better honors continuity with living Pueblo peoples. Language matters, and this shift acknowledges that these communities have adapted and continue to live on in today’s pueblos.

Unknown photographer, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown photographer, Wikimedia Commons

Fringe Theories: Aliens, Portals, And Lost Civilizations

Beyond science, wild ideas emerged to explain their “vanishing”—aliens abducted them, or portals spirited them away. These theories, found in pop culture, lack evidence but capture the public’s imagination. Enduring mysteries sometimes inspire speculation far removed from archaeology’s grounded discoveries.

Climate And Conflict Over Myth And Mystery

Archaeological science consistently indicates that drought, depleted resources, malnutrition, and conflict are key forces of change. Real people faced tangible struggles. Understanding these grounded causes gives richer respect for their resilience and places their story firmly in the history of human adaptation.

Grand Canyon National Park, Wikimedia Commons

Grand Canyon National Park, Wikimedia Commons

Mesa Verde Was Declared A National Park In 1906

Mesa Verde’s cliff dwellings gained protection in the early 20th century. Visitors today climb ladders into Cliff Palace or Balcony House, walking the same routes Ancestral Puebloans once used. These preserved spaces stand as monuments to ancient skill and enduring legacy.

Chaco Canyon Becomes A World Heritage Site

Chaco’s vast ruins, astronomical alignments, and massive great houses earned UNESCO World Heritage status in 1987. Recognition of its global significance ensures that this cultural heartland remains a place of study and respect for generations to come.

Gerd Eichmann, Wikimedia Commons

Gerd Eichmann, Wikimedia Commons

Ancient Sites Continue To Guide Astronomical Research

Even now, researchers continue to examine how sunlight and moonlight interact with the petroglyphs and the kivas they constructed. Ancient builders left astronomical records carved in stone at these sites, which continue to inform modern science.

Urban~commonswiki, Wikimedia Commons

Urban~commonswiki, Wikimedia Commons

The Mystery Endures

Despite decades of study, questions remain. Migration, drought, and conflict explain much, but gaps persist in the record. This uncertainty is part of the allure. The Ancestral Puebloans left behind not only ruins but an enduring mystery that continues to captivate.

National Park Service Digital Image Archives, Wikimedia Commons

National Park Service Digital Image Archives, Wikimedia Commons