Faith Vs Power

One declared loyalty to a blazing sun (henotheistic Atenism), the other to an unseen God. Fringe theories speculate on influence, but mainstream historians reject connections given the chronological gaps and distinct religious traditions.

Meet Moses

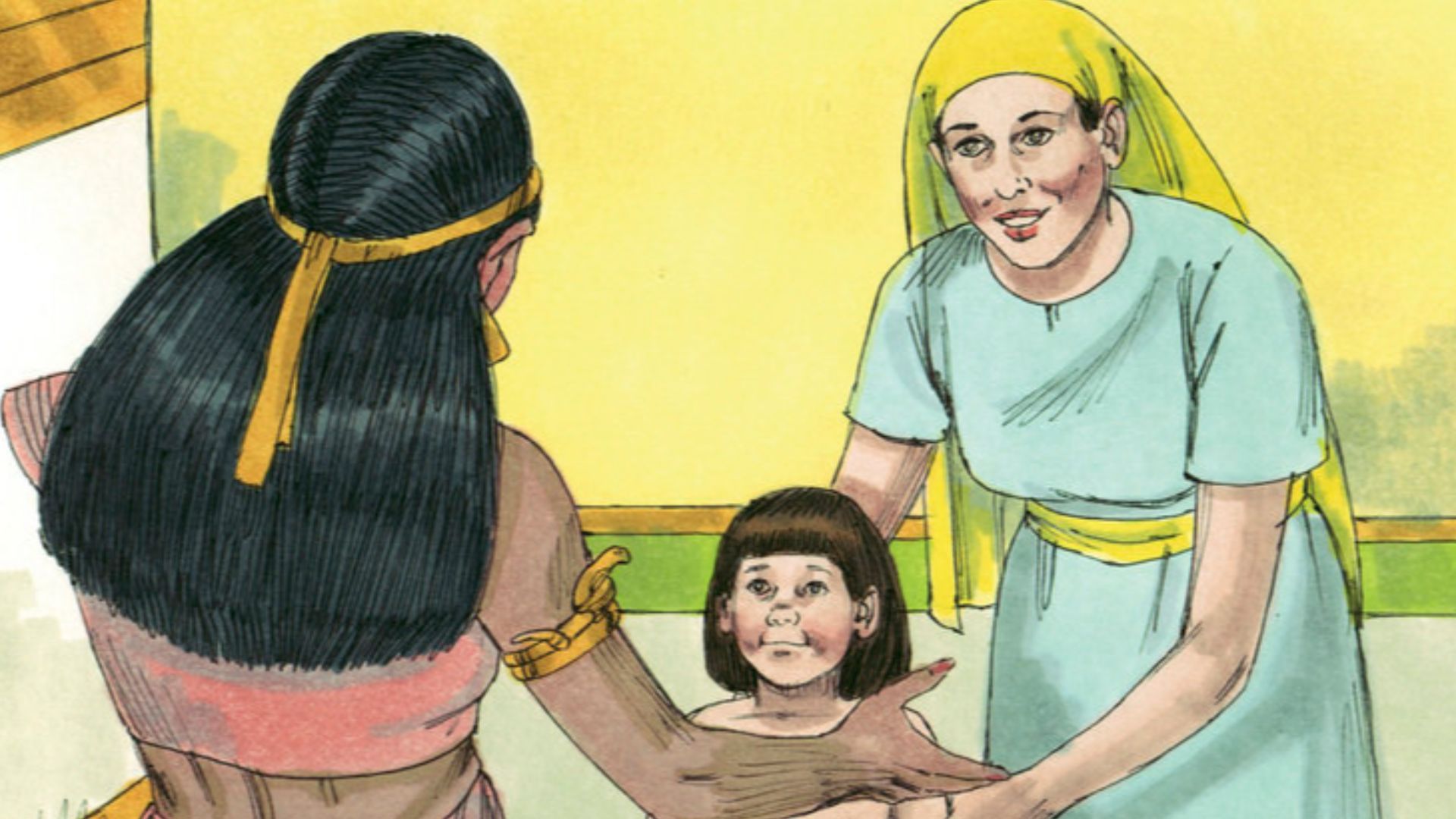

Exodus describes the birth of Moses to Amram and Jochebed, members of the Levite tribe. In those days, the Pharaoh at the time had ordered Hebrew boys killed, so his mother hid him in a basket on the Nile. Pharaoh’s daughter discovered him and raised him as her own.

James Tissot, Wikimedia Commons

James Tissot, Wikimedia Commons

Why Was The King Killing Hebrew Boys In The First Place?

Pharaoh’s harsh decree in Moses’s time came from fear, as recorded in the biblical tradition (Exodus 1:9–22), though modern scholarship views the Exodus as legendary with possible historical kernels. The Pharaoh’s response was enslavement and the chilling command that every newborn Hebrew boy be put to death.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

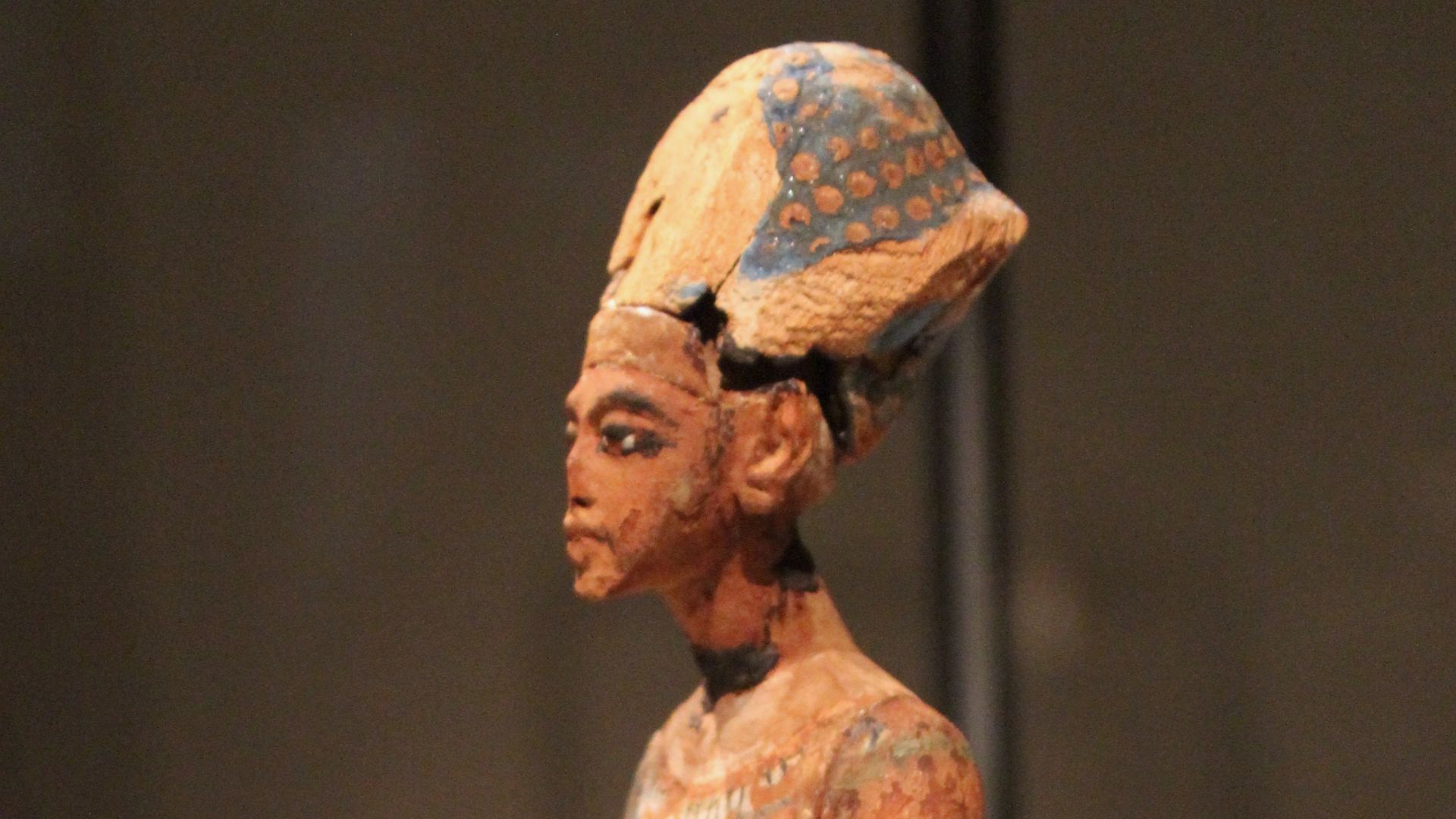

Meet Akhenaten

Akhenaten, originally named Amenhotep IV, was born in the royal palace at Thebes. His father was Pharaoh Amenhotep III, a ruler of immense wealth and influence, and his mother was Queen Tiye, a politically influential figure in her own right.

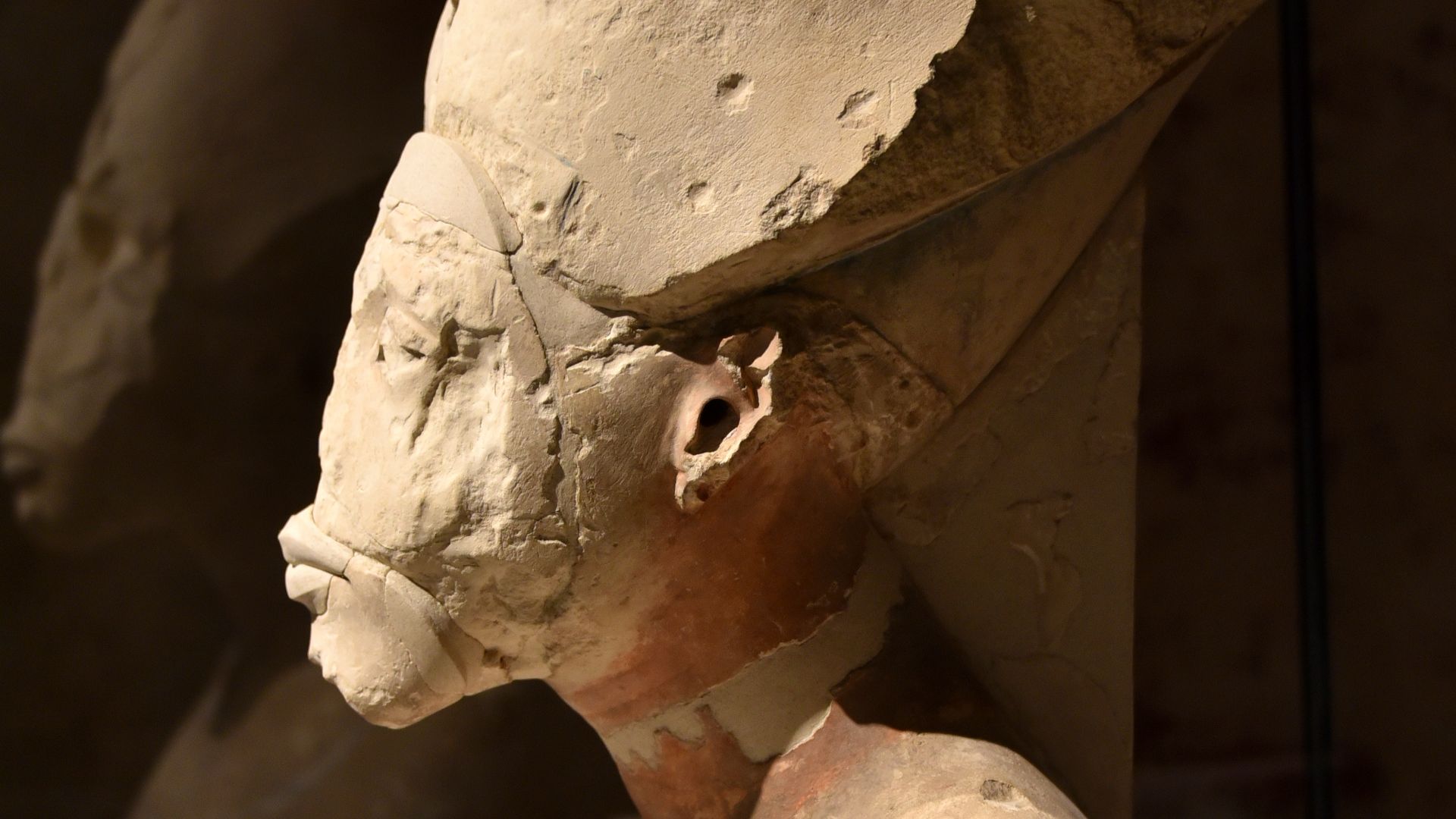

Akhenaten Had Some Peculiarities

Although rarely depicted in early art, Akhenaten's later portrayals during the Amarna period reveal elongated limbs, a narrow face, and wide hips—features that once sparked medical theories, such as Marfan syndrome (now ruled out) or endocrine disorders. These speculations are now seen as deliberate artistic symbols of Aten's androgyny.

Miguel Hermoso Cuesta, Wikimedia Commons

Miguel Hermoso Cuesta, Wikimedia Commons

Why People Think The Two Might Be Linked

Akhenaten shook Egypt’s order by lifting Aten above all gods. Moses led Israel into a covenant with one God. Both opposed powerful systems and lived in nearby eras. Another similarity? They both dramatically changed religion, which sparks curiosity about a possible connection. Let’s explore that, starting with Akhenaten’s story.

Ihab mohsen, Wikimedia Commons

Ihab mohsen, Wikimedia Commons

Akhenaten Steps Into Power

Akhenaten claimed the throne of Egypt around 1353 BC. His reign fell within the mighty Eighteenth Dynasty, an age of wealth, prestige, and imperial reach. You can still read his original titulary, carved deep into the limestone walls across Karnak.

René Hourdry, Wikimedia Commons

René Hourdry, Wikimedia Commons

A Pharaoh Changes His Name

In his early years, Akhenaten abandoned “Amenhotep,” meaning “Amun is satisfied,” and adopted “Akhenaten,” or “Effective for Aten”. Every Egyptian ruler’s name carried heavy symbolism, and this change marked his loyalty to a single divine force.

Prof. Mortel, Wikimedia Commons

Prof. Mortel, Wikimedia Commons

The Reason He Got The Name “Heretic Pharaoh”

This pharaoh earned the title “Heretic Pharaoh” because he defied Egypt’s deeply rooted religious traditions. For centuries, Egyptians worshiped a vast pantheon of gods. Akhenaten dismantled this system and declared Aten—the sun disk—the sole deity, and suppressed all others.

Jean-Pierre Dalbéra from Paris, France, Wikimedia Commons

Jean-Pierre Dalbéra from Paris, France, Wikimedia Commons

After That, Reforms Followed

The closing of temples that served other gods initiated the reforms, which erased references to rival gods. To replace them, he built Aten shrines inside the sacred precincts of Amun, which was seen as sacrilegious. By weakening the powerful Amun priesthood, he centralized religious authority under himself.

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

He Even Built A Brand-New Capital City

The leader even went so far as to construct Akhetaten (Amarna) in Middle Egypt. It stood midway between Memphis and Thebes, untouched by older cult centers. The city grew quickly, featuring open-air temples, palaces, and sprawling villas. Today, archaeologists uncover clay tablets known as the Amarna Letters there.

en:User:Markh, Wikimedia Commons

en:User:Markh, Wikimedia Commons

Things Took A Domino Effect

Centuries of tradition were swept away as Akhenaten ordered more temples of Amun to be sealed. Vast estates and wealth once belonging to the Theban cult were redirected to Aten. For everyday Egyptians, this meant changes to festivals and even burial rites.

Egypt’s Elite Grow Restless

Priests who lost influence under Atenism grew hostile. Because of this, monuments carved later show Pharaohs erasing Akhenaten’s name in retaliation. The backlash wasn’t swift, but it was fierce. These religious leaders were deeply offended, as they had lost land, authority, and their ancestral ties to the gods.

Georges Legrain (1865-1917), Wikimedia Commons

Georges Legrain (1865-1917), Wikimedia Commons

A Hebrew Child On The Nile

Now turn to the biblical account. Exodus records the birth of Moses under Pharaoh’s harsh decrees. His mother hid him in a papyrus basket coated with pitch. Pharaoh’s daughter discovered him among the reeds, and Moses grew up in Egypt’s royal household.

Illustrator of Bible, Wikimedia Commons

Illustrator of Bible, Wikimedia Commons

An Egyptian Court Education

Raised in the palace, Moses would have learned everything from writing to mathematics to diplomacy, just like a typical Egyptian noble. Exodus highlights his Hebrew roots, yet his education equipped him with the leadership skills necessary for his role.

Jim Padgett, Wikimedia Commons

Jim Padgett, Wikimedia Commons

All Seemed Well, Until He Took The Life Of Another Egyptian

After growing up in Pharaoh’s household, Moses witnessed an Egyptian taskmaster beating a Hebrew slave—“one of his own people” as per biblical narrative (Exodus 2:11–12), though seen as a legendary motif by scholars. Moved by outrage and a sense of justice, Moses struck the Egyptian dead.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

If No One Saw, He Was Safe, Right?

Wrong. The very next day, a Hebrew man confronted him, saying, “Are you going to kill me as you killed the Egyptian?” (Exodus 2:14), as per the biblical account, revealing that someone had learned of the incident. Pharaoh soon sought to punish him. He ran away.

In Midian, Life Started Afresh

After fleeing, Moses settled in Midian, where he lived as a shepherd and married Zipporah, daughter of the priest Jethro. He named his son Gershom, stating, “I have become a foreigner in a foreign land” (Exodus 2:22). For forty years (per tradition in Acts 7:30), Moses led a quiet life.

the Providence Lithograph Company, Wikimedia Commons

the Providence Lithograph Company, Wikimedia Commons

God Appeared To Him

Then, one day, according to the narration in Exodus 3, God appeared to him at Mount Horeb in a burning bush, commanding him to return to Egypt and free the Israelites. Though reluctant, Moses accepted the mission. His time in Midian transformed him from a royal fugitive into a humble leader.

Illustrators of the 1897 Bible Pictures and What They Teach Us by Charles Foster, Wikimedia Commons

Illustrators of the 1897 Bible Pictures and What They Teach Us by Charles Foster, Wikimedia Commons

Demands Before Pharaoh

According to Exodus, Moses returned to Egypt decades later. Standing in Pharaoh’s court, he demanded freedom for the Israelites. “Let my people go” became the repeated cry. Each refusal brought plagues on Egypt, from the waters turning to blood to locust swarms devouring crops.

James Tissot, Wikimedia Commons

James Tissot, Wikimedia Commons

The Final Plague Strikes

The climax came with the passing of Egypt’s firstborn sons. Israelites marked their doors with lamb’s blood, following Moses’s command. That night’s event became Passover, a cornerstone of Jewish tradition. Pharaoh, broken by grief, ordered the Hebrews to leave immediately.

Charles Sprague Pearce, Wikimedia Commons

Charles Sprague Pearce, Wikimedia Commons

The Red Sea Crossing

Exodus describes the Israelites's final escape from the Egyptians as the Red Sea waters parted miraculously. Egyptian chariots pursued because Pharaoh had changed his mind, but the sea closed upon them. Ancient hymns celebrate this deliverance: “Horse and rider He has hurled into the sea”.

the Providence Lithograph Company, Wikimedia Commons

the Providence Lithograph Company, Wikimedia Commons

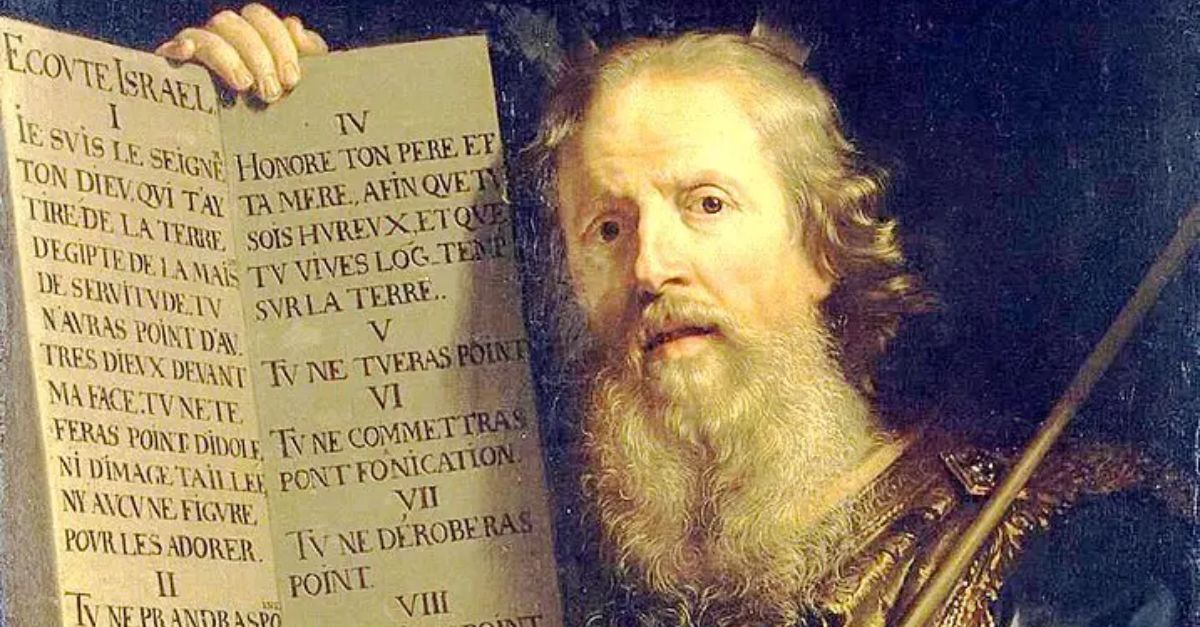

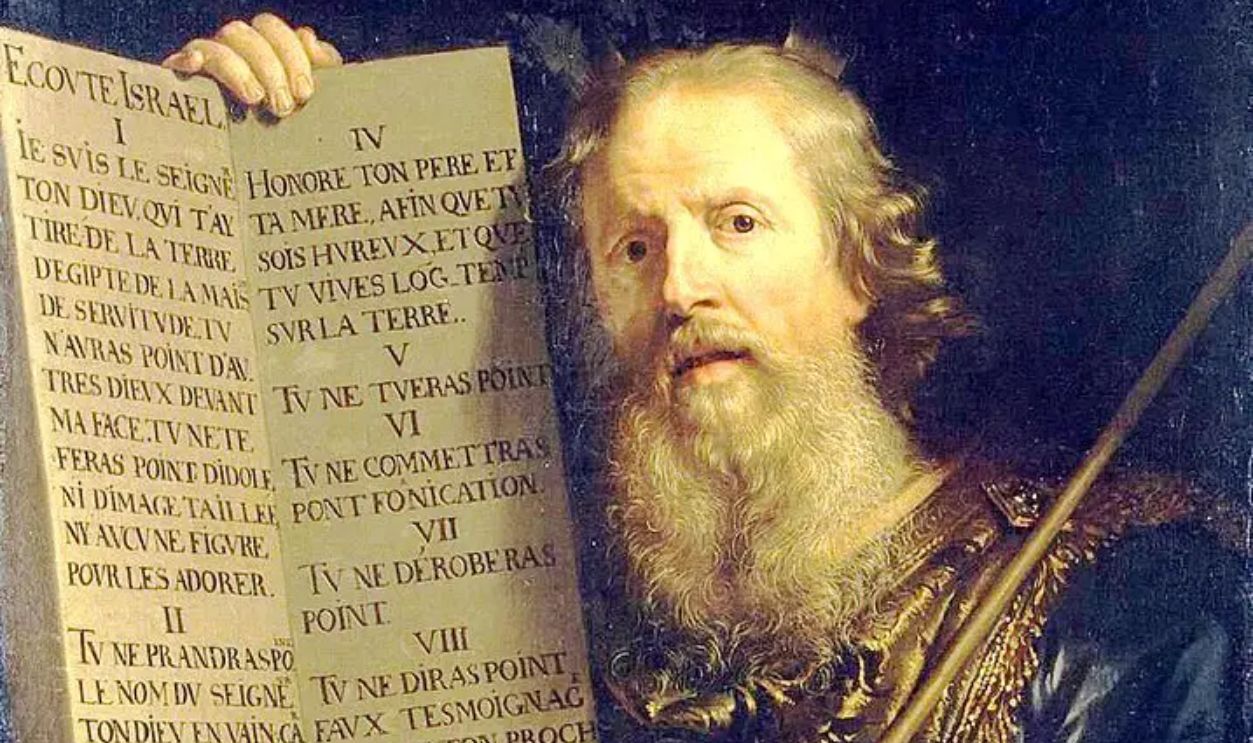

Law At Mount Sinai

In the wilderness, Moses climbed Mount Sinai. There, he received tablets inscribed with the Ten Commandments. Unlike Atenism’s solar focus, this covenant introduced moral and ethical codes—no theft, no murder, no false witness. Israel’s national life revolved around these divine laws.

A New Religious Community

Unlike Akhenaten’s reforms from above, Israel’s faith grew from a shared covenant. Every tribe pledged loyalty to Yahweh. Daily life involved sacrifices and festivals outlined in the Torah. The entire community carried responsibility, not just a royal household.

Dating The Exodus

Pinpointing the Exodus date remains debated. Exodus 1:11 ties it to the 13th century BC, while Judges 11:26 hints at a 15th-century event. The Merneptah Stele (c. 1208 BC) mentioning Israel in Canaan strengthens the case for a 13th-century Exodus under Ramesses II.

Olaf Tausch, Wikimedia Commons

Olaf Tausch, Wikimedia Commons

Chronology Versus Amarna

Akhenaten’s passing occurred around 1334 BC. Even using the earliest proposed dates, Moses’s story occurs decades later. Later timelines stretch that gap to over a century. Simply put, their lives do not overlap. Historical evidence separates them by at least one generation.

Anonymous (Egypt)Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Anonymous (Egypt)Unknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Different Origins, Different Paths

Moses was Hebrew by birth, Egyptian by upbringing. Akhenaten was Egyptian royalty from birth to death. One led slaves to covenant freedom, the other reigned as Pharaoh, enforcing new rituals. No records ever cross their names to link them in real history.

Carol M. Highsmith, Wikimedia Commons

Carol M. Highsmith, Wikimedia Commons

Egypt Records Silence

Egyptian scribes recorded triumphs and temple dedications, not humiliating defeats. That’s why events like the Exodus don’t appear in Egyptian archives. However, their silence doesn’t mean the events never happened—it reflects how official inscriptions functioned as propaganda to preserve only glory for posterity.

Jon Bodsworth, Wikimedia Commons

Jon Bodsworth, Wikimedia Commons

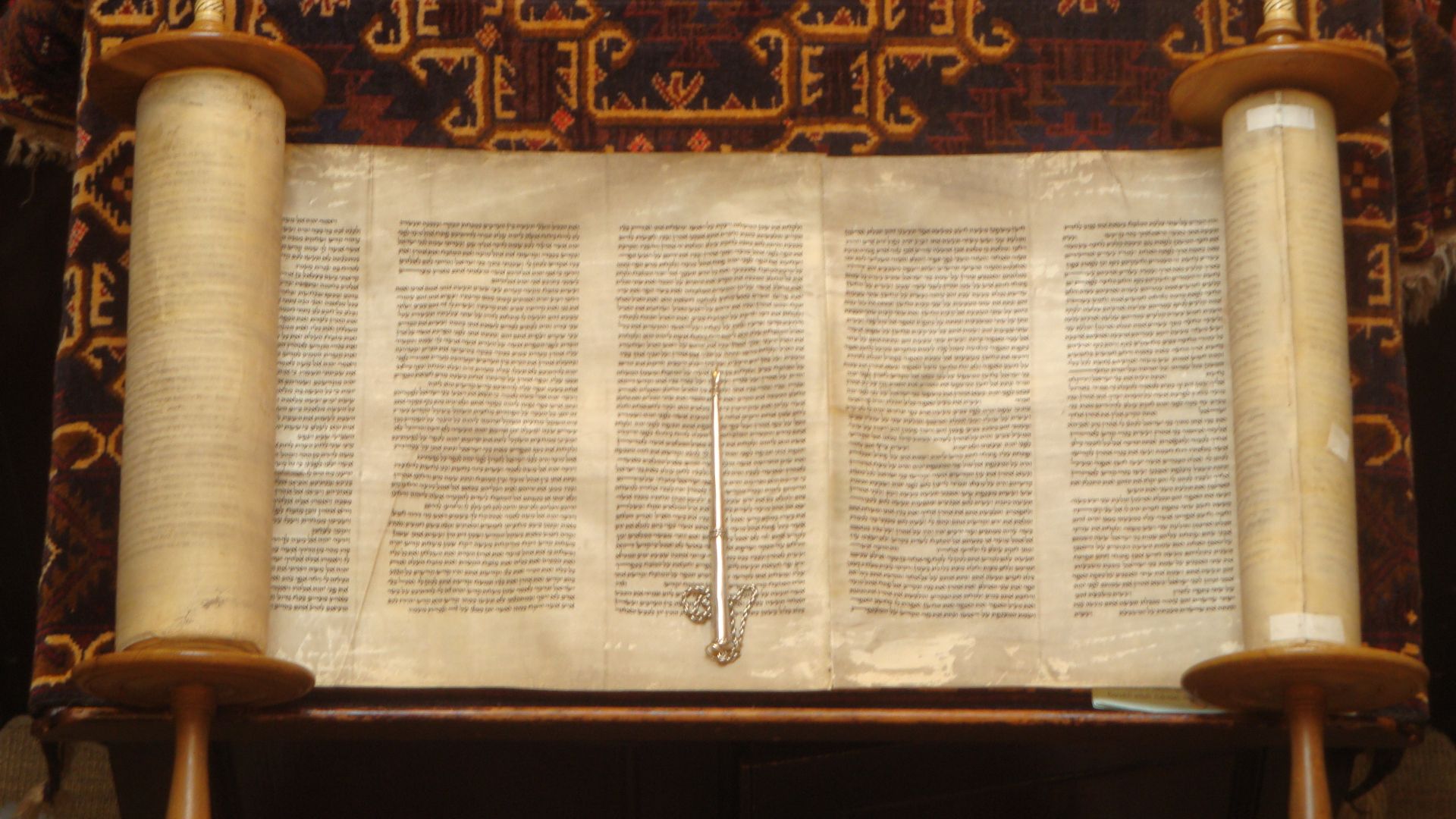

Memory Preserved In Scripture

While Akhenaten’s name nearly vanished from Egyptian history, Moses’s memory thrived through Israel’s sacred texts. Generations copied and read the Torah aloud. His story transcended Christianity and Islam, making him central to three global faiths practised by billions today.

Lawrie Cate, Wikimedia Commons

Lawrie Cate, Wikimedia Commons

Pharaohs And Building Projects

Exodus notes the Israelites building the cities of Pithom and Raamses. Pharaohs often conscripted labor forces for monumental works. Ramesses II, who ruled in the 13th century BC, left inscriptions boasting of grand cities and temples, which align with that biblical reference.

Unknown artistUnknown artist, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown artistUnknown artist, Wikimedia Commons

Judges Timeline Evidence

Centuries later, Judge Jephthah declared that Israel had lived in Canaan for 300 years. His statement, recorded in Judges 11:26, points toward an earlier Exodus. This makes historians weigh both internal biblical markers and Egyptian dynastic chronology carefully.

MartinPoulter, Wikimedia Commons

MartinPoulter, Wikimedia Commons

The Great Dating Debate

Some propose a 15th-century Exodus under Pharaoh Thutmose III. Others argue for a 13th-century date under Ramesses II. Each view has archaeological backers, yet both positions fall after Akhenaten’s reign ended. This alone makes linking Moses to him historically untenable.

Richard Mortel from Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, Wikimedia Commons

Richard Mortel from Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, Wikimedia Commons

Archaeological Separations

Archaeologists digging at Amarna uncover letters from foreign rulers begging Akhenaten for military aid. None directly mentions Hebrews, plagues, or mass migrations, though references to “Habiru” (nomadic outsiders possibly linked to early Hebrews in scholarly debate) appear in diplomatic contexts unrelated to Exodus events.

Akhenaten’s Passing Recorded

Ancient king lists confirm Akhenaten died around 1334 BC. His burial at Amarna left fragments of his passing. Later, his body was reburied. By contrast, Moses’s departure location, as stated in Deuteronomy 34:5, was in the plains of Moab, present-day Jordan. But the burial spot remains unknown.

the Providence Lithograph Company, Wikimedia Commons

the Providence Lithograph Company, Wikimedia Commons

Hebrew Identity Maintained

Despite his Egyptian schooling, Moses remained connected to his people. Exodus 2 recounts his defense of a Hebrew slave, a choice that cost him his position. His decision to align with Israel defined his destiny, unlike Akhenaten’s royal continuity in Egypt.

James Tissot, Wikimedia Commons

James Tissot, Wikimedia Commons

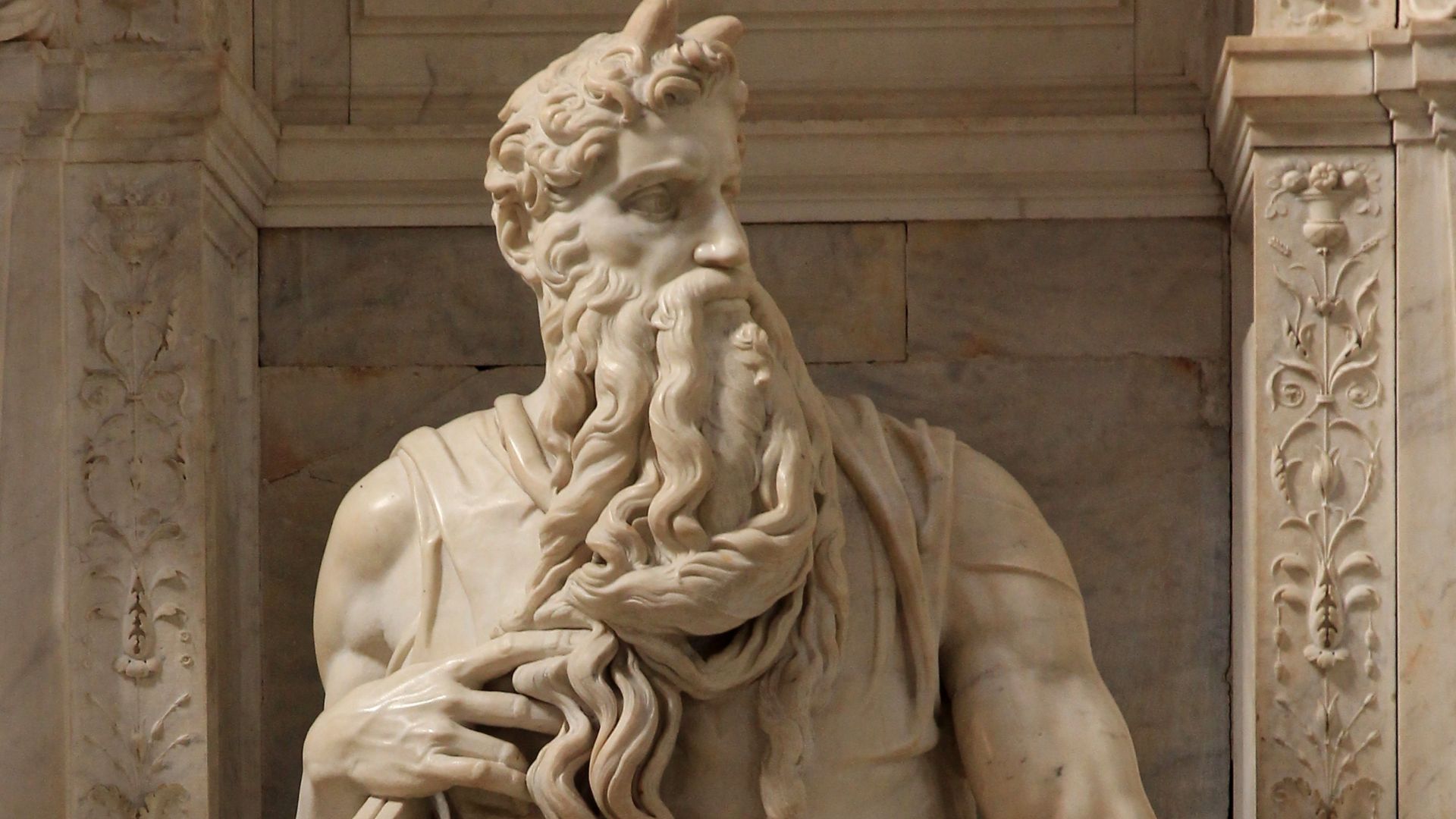

Prophetic Role, Not Royal

Moses never claimed kingship. Instead, he stood as prophet, mediator, and lawgiver. His leadership relied on signs and covenant, not palaces or armies. Akhenaten, in contrast, ruled from gilded halls, where he issued decrees that shaped religion from the top down.

Inscriptions And Reliefs

Reliefs at Amarna show Akhenaten with his wife Nefertiti and daughters worshiping Aten. Rays extend from the sun disk, ending in little hands offering life. Biblical inscriptions about Moses, however, survive only in texts—not carved monuments—but have become far more influential.

myself (Gerbil from de.wikipedia), Wikimedia Commons

myself (Gerbil from de.wikipedia), Wikimedia Commons

The Pharaoh As Mediator

In Atenism, only Akhenaten and his family stood between Aten and humanity. Ordinary Egyptians accessed divine favor through the royal household. This differs sharply from the covenant Moses introduced, where every Israelite shared responsibility in obeying divine law.

An Invisible God

Moses introduced a God who could not be seen or shaped. The Israelites were forbidden to make images. Egyptian religion, even Atenism, used visible symbols like the radiant sun disk. That contrast highlights one system based on physical form and another on transcendence.

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

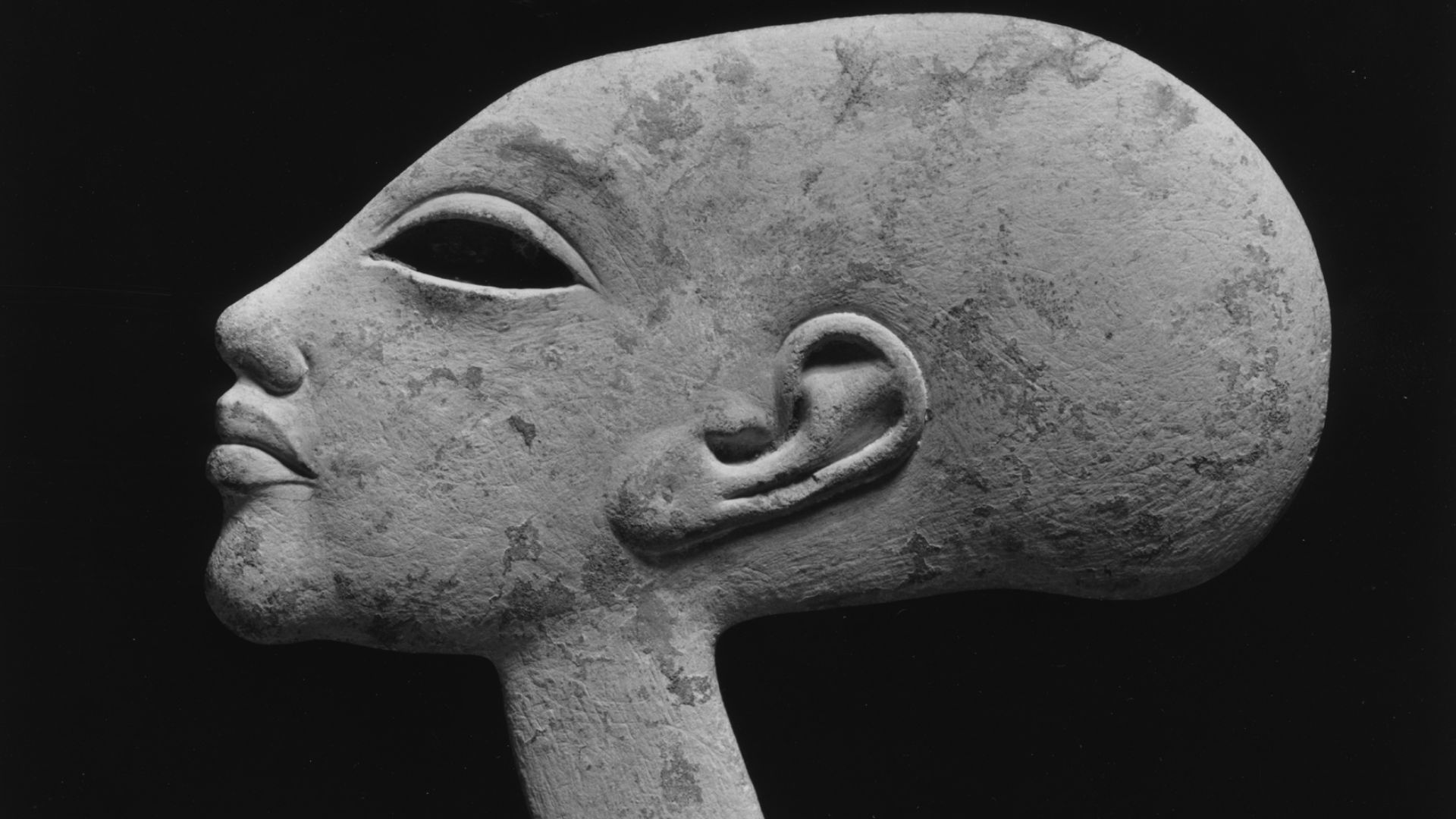

Tutankhaten (Tutankhamun) Succeeded Akhenaten

Born into Akhenaten’s court, the boy-king first carried the name Tutankhaten, “Living Image of Aten”. Advisors soon shifted his identity, changing it to Tutankhamun, “Living Image of Amun”. That symbolic renaming marked Egypt’s sharp turn away from Atenism.

Roland Unger, Wikimedia Commons

Roland Unger, Wikimedia Commons

Tutankhamun Restores Tradition

Once enthroned, Tutankhamun actively reinstated Egypt’s old religious system. Temples to Amun reopened, and priestly estates regained prominence. His burial treasures, decorated with Osiris and Horus imagery, show how Egypt fully embraced familiar gods and chose to leave Aten in the shadows.

Fading Reforms Vs Enduring Traditions

Atenism collapsed soon after Akhenaten’s passing, around 1336 BC, lasting less than two decades—proof of how fragile top-down reforms could be. In contrast, based on biblical text, Moses’s covenant endured centuries of exile. Festivals such as Passover and Sukkot kept identity alive.

Differing Global Legacies

Akhenaten became infamous as a “heretic Pharaoh,” nearly forgotten until 19th-century archaeologists uncovered the ruins of Amarna. By contrast, Moses is credited with shaping three major world religions. Judaism, Christianity, and Islam all revere him as a prophet and lawgiver.

Jörg Bittner Unna, Wikimedia Commons

Jörg Bittner Unna, Wikimedia Commons

Erased Vs Preserved Memories

Egypt sought to erase Akhenaten entirely. His name vanished from king lists at Abydos and Saqqara, and his cartouches were chiseled off monuments; statues smashed or recycled. Meanwhile, Moses’s memory was deliberately preserved. Hebrew scribes copied Torah scrolls, synagogues read his story aloud, and families passed it to children.

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), Wikimedia Commons

Worlds Apart In History

Both men influenced religion, yet evidence shows they lived in separate times, followed different callings, and left opposite legacies. Akhenaten reshaped Egypt briefly; Moses shaped the identity of Israel forever. History leaves them not united, but undeniably worlds apart.

illustrators of the 1890 Holman Bible, Wikimedia Commons

illustrators of the 1890 Holman Bible, Wikimedia Commons