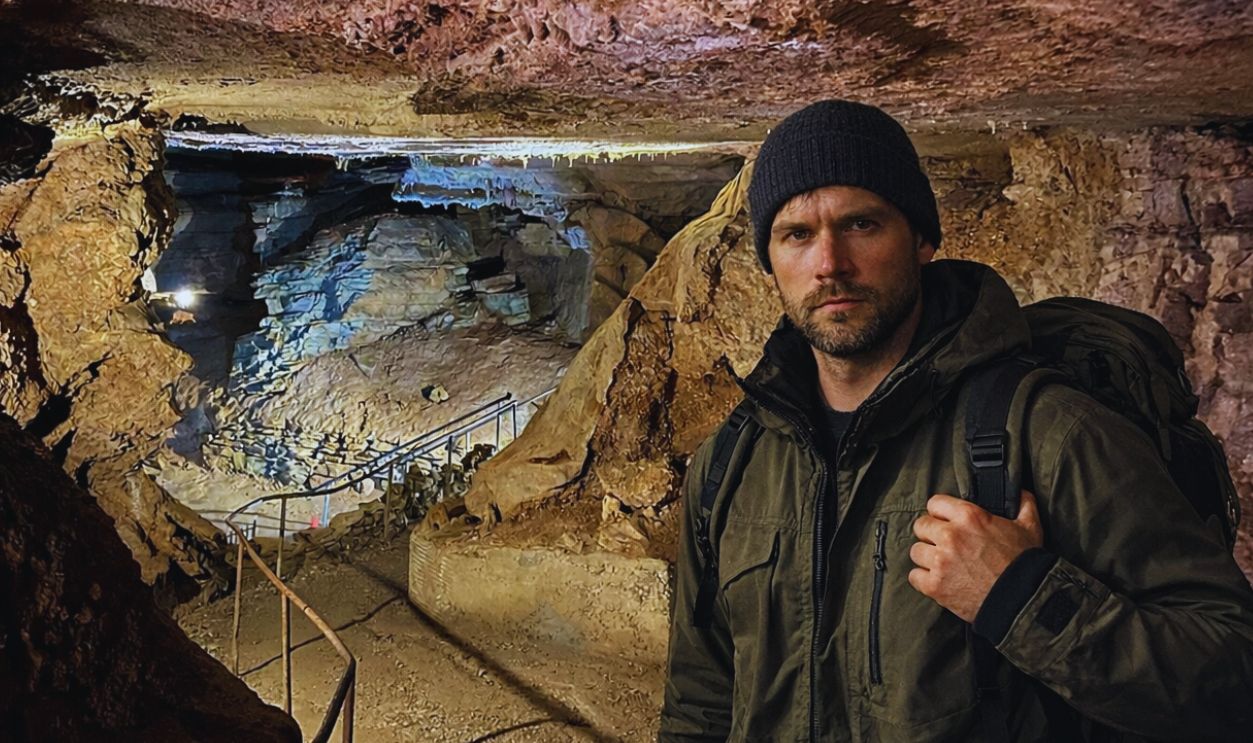

Cavecouple, Wikimedia Commons, Modified

Cavecouple, Wikimedia Commons, Modified

Located east of Malaga, Treasure Cave long attracted divers and visitors without revealing its deeper historical importance. That changed when researchers identified human footprints preserved in ancient sediment inside the cave. Formed by bare feet more than 40,000 years ago, these impressions survived as sea levels rose and shorelines shifted. Their age places them among the oldest known human footprints in the Mediterranean region. This discovery forced archaeologists to reassess early human activity along southern Europe’s coast and provided direct evidence of how early groups moved through and used coastal environments.

Footprints That Refused To Wash Away

Treasure Cave, known locally as Cueva del Tesoro, stands as one of Europe’s few marine caves formed by seawater rather than rivers. Located about 10 feet above present sea level in Rincon de la Victoria, it once opened directly onto the coast. Researchers identified fossilized human footprints preserved in hardened sediment layers inside chambers now partially flooded. Scientific analysis dates these impressions to over 40,000 years ago, placing them in the Upper Paleolithic period. Their size and spacing suggest adults and possibly adolescents walked through the cave, likely during brief visits rather than long-term shelter. Importantly, erosion patterns show the tracks formed before rising seas submerged sections of the cave, locking them safely beneath mineral deposits.

That shift in context draws attention from the footprints themselves to the timing. Around 40,000 years ago, modern humans were expanding across Europe while Neanderthals faded from the archaeological record. Southern Iberia has long been debated as one of the last regions where Neanderthals survived. These footprints push human presence along the Mediterranean coast further back than many coastal sites allow, largely because rising seas erased earlier evidence elsewhere. Here, nature did the opposite. Mineral-rich water sealed the prints like plaster. As a result, you are looking at movement frozen mid-step that offers a direct record of human activity rather than tools or bones left behind.

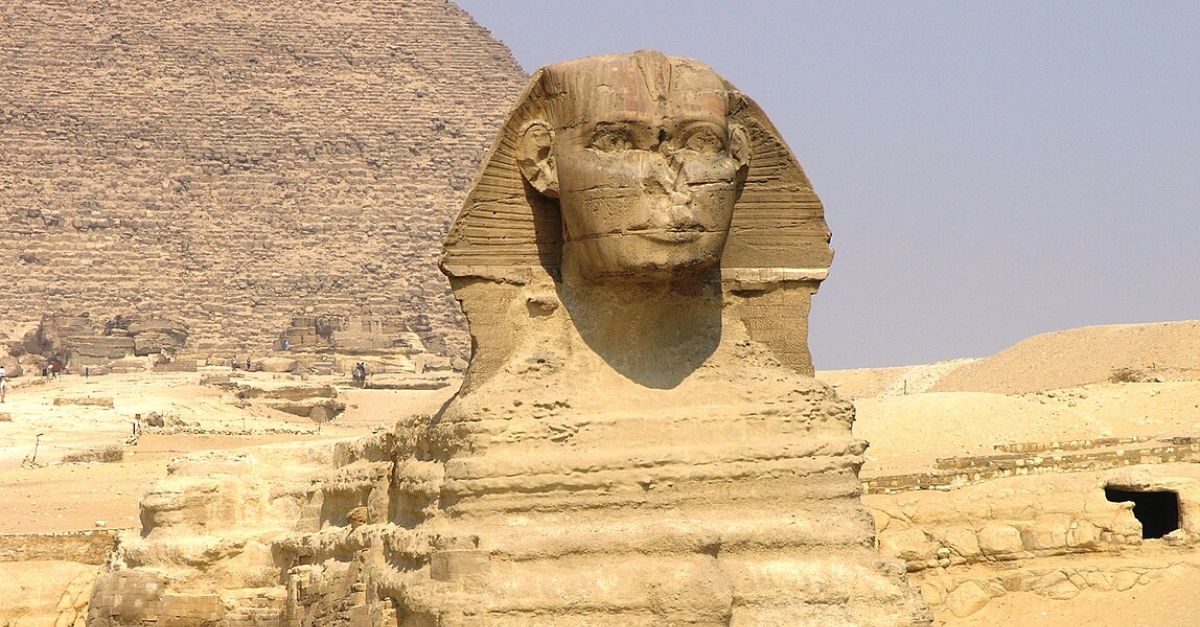

JamesNarmer, Wikimedia Commons

JamesNarmer, Wikimedia Commons

A Cave That Breaks The Usual Archaeology Rules

Unlike dry inland caves, Treasure Cave formed through marine erosion, with waves carving chambers over thousands of years. This matters because human traces inside sea caves rarely survive. Most coastal Paleolithic sites disappeared as ice ages ended and sea levels rose more than 300 feet. Treasure Cave escaped that fate due to its elevation and complex structure. According to geological studies, sections of the cave remained dry long enough for humans to enter, walk across soft sediment, and leave footprints before later flooding occurred. That sequence explains why prints survived while organic material did not.

Equally striking is what was not found. No hearths, no butchered bones. That absence suggests short visits, perhaps for shelter or ritual curiosity. Archaeologists caution against dramatic assumptions, yet the evidence supports a brief human presence rather than settlement. The footprints show direction changes and overlapping paths, indicating movement rather than rest. For readers used to dramatic cave art or skeletons, this site offers something quieter but arguably more powerful. It records behavior. You see how people walked, where they turned, and how groups moved together through unfamiliar terrain.

What These Steps Change About Mediterranean History

The implications extend beyond southern Spain. Coastal routes likely played a major role in early human migration, offering food, navigation landmarks, and milder climates. Yet physical proof along Mediterranean shores remains scarce. These footprints fill part of that gap, especially in a region where rising seas erased much earlier evidence. They confirm humans occupied coastal southern Iberia tens of thousands of years earlier than many shoreline sites suggest. That strengthens theories proposing that early humans followed coastlines rather than inland corridors as they spread westward across Europe.

This discovery also reframes how future research approaches submerged or partially flooded sites. Treasure Cave demonstrates that valuable evidence may survive where conditions align just right. For you as a reader, it sharpens an important point: history often hides in overlooked places. A cave once dismissed as a curiosity now anchors debates about human migration and coexistence with Neanderthals. Each footprint adds weight to the idea that coastal Europe hosted complex human activity far earlier than textbooks once claimed. The past does not always shout. Sometimes it leaves quiet tracks and waits patiently to be seen.

Jakub Hałun, Wikimedia Commons

Jakub Hałun, Wikimedia Commons