Uncovering The Mysteries Of The Picts

The Picts first appeared in written history around 287 CE—then, just as mysteriously, vanished from it after 900 CE. But while their words faded, their presence never did. Across Scotland, their symbols still whisper from carved stones and linger in ancient place names. So who were these elusive people—and how did an entire nation simply disappear?

Where Did They Live?

The Picts lived in what we now call northern England and southern Scotland, with the bulk of their settlements being north of the Firth of Forth, in Scotland.

Historians call the territory “Pictland”, and though it started with only seven chiefdoms, it would later turn into one of Britain's most powerful kingdoms.

Their Name

The name “Pict” isn’t what the tribe originally called themselves. They took it on after years of being called “Picti” by the Romans.

“Picti” means “the painted ones” and refers to their practice of painting their bodies for battle.

The Caledonians

Before being known as Picts, they were called the Caledonians. The Caledonians were several different clans in northern Britain. They would band together to repel Roman attacks—and launch guerilla attacks of their own.

By the 3rd century CE, these tribes were a more unified political entity and the Romans called them “Picti”.

Mike Peel., CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Mike Peel., CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons

Their True Name

We still don’t know what exactly the Picts as a unified group called themselves, but some places names in Scotland offer a piece of the puzzle.

Many places that were once the site of ancient Pictish settlements begin with the word “Pit”—Pittodrie, Pitlochry, and Pittenweem are some examples.

The Guardian, King Arthur (2004)

The Guardian, King Arthur (2004)

Pictish Paint

Before charging into battle, the Picts transformed themselves into living works of paint—coating their bodies in a striking blue dye made from woad plants. The eerie color gave them a terrifying, almost otherworldly appearance on the battlefield and helped them recognize one another amid the chaos. As it turns out, their ritual wasn’t just for show—the woad’s natural antiseptic qualities also helped keep their wounds from festering after the fight.

Yatzek Photography, Shutterstock

Yatzek Photography, Shutterstock

Their Tattoos

The Picts were also known for their tattoos. Roman sources describe seeing them with tattoos all over their body, but the practice may not have been as common as we once thought.

Pictish stones depict reliefs of nobles and hunters without any visible tattoos.

Iantresman , Wikimedia Commons

Iantresman , Wikimedia Commons

Battle Uniforms

From Roman records, we know that the Picts usually fought with no clothes on.

While other tribes in history have done this, the Picts did it to show off their battle paint and tattoos, and strike fear into the hearts of their enemies.

First Encounters

The Picts’ first encounter with Rome occurred in 55 BC, when Julius Caesar invaded Britain. Caesar didn’t stay long, but in 43 CE, Emperor Claudius conquered much of the area, calling it the province of Britannia.

He couldn’t, however, maintain a foothold in the north—the Picts defended this land too fiercely.

Fierce Enemies

The Picts brought the fight to the Romans, and there are several historical accounts of them raiding Roman settlements in the British Isles.

They proved to be exceptional pirates, and often evaded counterattacks.

Good Business

Far from being the wild marauders Roman writers made them out to be, the Picts were savvy traders with connections that stretched far beyond their misty homeland. Archaeological finds suggest they played a role in trade routes reaching from Europe to the Middle East. In the Pictish stronghold of Rhynie, for instance, excavations have uncovered Mediterranean jugs and elegant glass beakers from France—clear proof that these so-called “barbarians” had a taste for the finer things.

Pictish Stones

Evidence of the Picts can be found in stone carvings all throughout Scotland.

Thus far, 300 Pictish Stones have been found, with most dating back to the 7th and 9th centuries.

Pictish Stones (cont’d)

The stones feature intricately carved designs and symbols. Some symbols depict unknown mythical beasts, while others show fearsome creatures like dragons.

Some also contain writing in Ogham, the ancient Irish alphabet.

The Pictish Beast

The Pictish Beast is a common motif on Pict Stones—40% of animal depictions are of the beast, so it must have been very important to the Picts.

When drawn upright, this unknown mythical animal looks like some sort of seahorse, or perhaps a dragon.

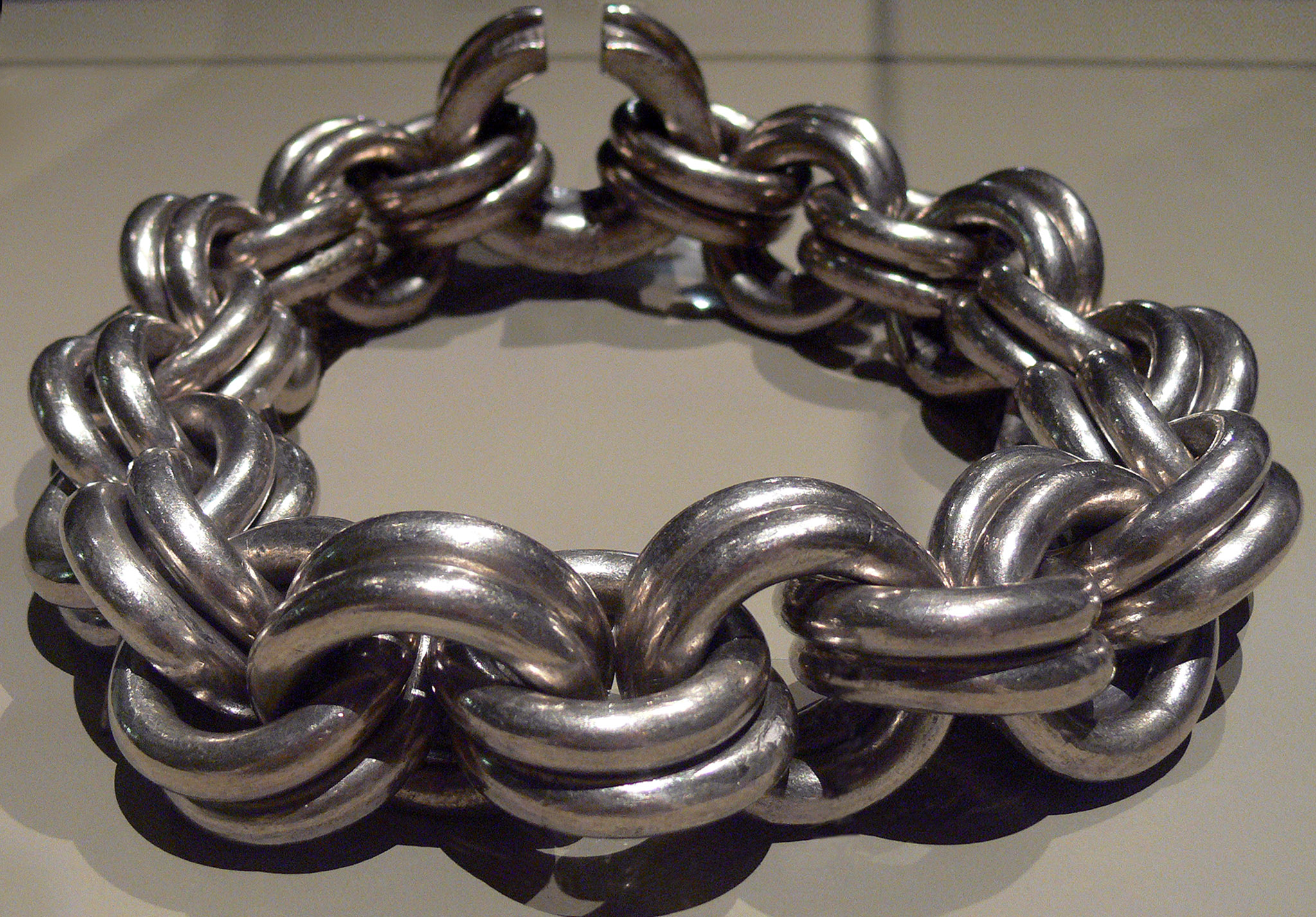

Pictish Metalwork

The Picts have also left behind some beautiful examples of metalwork. Silver chains, necklaces, plates, and broches are common finds in excavated Pictish settlements.

DNA Evidence

Modern science has revealed that the Picts never truly vanished—they just blended into the fabric of Scotland itself. A 2013 genetic study found that roughly 10% of Scottish men carry a Y-chromosome marker known as R1B-S530, a genetic signature unique to ancient Pictish communities. Even more striking, newer research shows that around 20% of people living in what was once Pict heartland—Tayside, Perthshire, Fife, and Angus—still carry traces of Pictish ancestry in their DNA.

B4bees, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

B4bees, CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Their Rulers

Early Pictish society was made up a series of politically autonomous clans, and each clan was led by a chieftain.

From the Roman records, it seems that during times of war, the clans would come together and elect one chief to lead them in battle.

Pict Kingdoms

In the later centuries, the Picts adopted a system in which one, or sometimes, two kings would rule over their own kingdom.

Legends and historical records from the 11th and 13th centuries name seven Pictish kingdoms: Cait, Cé, Circin, Fib, Fidach, Fotla, and Fortriu.

Pict Kingdoms (cont’d)

There may have been a few smaller kingdoms, and archeological evidence suggests there was probably a minor Pictish kingdom in Orkney.

Regardless of how many there actually were, the kingdom of Fortriu was the most powerful.

Pictish Women

Women in Pictish society were highly respected, and the succession of chiefs was usually matrilineal.

From records of later Pictish kings, it seems that they could be succeeded by a brother or their mother’s nephew but could not pass leadership down from father to son.

Their Language

No written records of the Pictish language have survived, leaving their words lost to time. However, clues hidden in ancient place names and personal names suggest that the Picts spoke a Celtic tongue—one closely related to modern Breton, Welsh, and Cornish. Though the language itself has vanished, its echoes still ripple through the landscapes of Scotland.

Pictish Communities

Archaeological sites have given us a glimpse into what Pictish societies looked liked. Primarily, they were farmers who lived in small communities, or familial clans.

Their staple crops were grains like wheat, barley, and rye but they also would have grown vegetables like cabbage and beans, too.

Pictish Communities (cont’d)

Livestock were also very important to the Picts, with cattle and horses being signs of wealth and power.

Large flocks of sheep and pigs were also common and would have been vital for their wool and meat.

Ray Berry, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Ray Berry, CC BY-SA 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Pict Clothes

When they weren’t in battle, the Picts dressed in clothing made from wool, leather, and fur pelts. They also wove linen fabric from flax fibres.

Long tunics and cloaks seem to have been common dress for women and monks, while calf-length tunics and trousers were common among men.

Brochs

Some historians believe that the early Picts built large round structures called brochs.

We still don’t know what these buildings are for, but historians think they may have been defensive structures or houses for powerful clan members.

Colin Smith, CC BY-SA 2.0 , Wikimedia Commons

Colin Smith, CC BY-SA 2.0 , Wikimedia Commons

Crannogs

Crannogs existed long before the Picts ever appeared in written history—but these mysterious island homes were still part of their world. Built on lakes and waterways, crannogs were man-made islands topped with wooden dwellings, offering both protection and seclusion. Scotland still boasts around 389 of these ancient structures today, while Ireland has over 1,200—silent reminders of a time when people literally built their homes on the water.

Dave Morris , CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

Dave Morris , CC BY 2.0, Wikimedia Commons

A New Opponent

40 years after Emperor Claudius had secured most of Britannia under Roman control, a general named Julius Agricola decided the north needed to be brought to heel, too.

In 83 CE, he launched an invasion of the north, facing off with the Picts—who were then called Caledonians—in the Battle of Mons Graupius.

The Battle Of Mons Graupius

According to the ancient historian Tacitus, the Battle of Mons Graupius was a great victory for Rome which saw General Agricola face off against a Calgacus, a Caledonii chieftain.

The Caledonii were the last unconquered tribes in Britain—and though Rome won the battle, they could not say they ever truly defeated the Caledonii.

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown Author, Wikimedia Commons

The Battle Of Mons Graupius (cont’d)

The Romans were severely outnumbered, with Tacitus claiming that 11,000 auxiliaries defeated 30,000 Picts.

By the end of the fight, 10,000 Picts lay dead, while the Romans only lost 360 fighters. The Picts retreated into the forest, never to be seen again.

If all that sounds too good to be true, that’s probably because it is.

What Really Happened?

The truth of Tacitus’ account has been questioned by modern historians, with many believing that the battle never actually happened.

If they won, why didn't the Romans capitalize on the victory and press further north? And there are no records of any other successful battles against the Picts.

What Really Happened? (cont’d)

Historians now believe the Romans may have met their match in the Picts rather than overwhelming them as old accounts suggest. Both sides likely fielded armies of 15,000 to 30,000 soldiers, making the battles far more balanced than Roman historians—like Tacitus—claimed. While the Picts certainly took their share of losses, the evidence suggests their defeat was far less catastrophic than the Romans wanted the world to believe.

The Truth

Despite the truth of Tacitus’ account, it does seem that some kind of battle occurred, as in Rome, they proclaimed that Agricola had conquered all the tribes of Britain.

He was given another governorship and the Picts remained free.

William Brassey Hole, Wikimedia Commons

William Brassey Hole, Wikimedia Commons

The Wall

After years of skirmishes and failed attempts to gain ground in the north, the Romans switched tactics.

In 122 CE, Emperor Hadrian constructed his world-famous wall, separating Roman-controlled Britannia from the unconquered north, which we now call Scotland.

New Invaders

Rome recalled their forces from the British Isles in the early 5th century—Germanic tribes like the Franks and Visigoths were on their doorstep.

Over the next few centuries, Pictish settlements were routinely invaded by Scots and Gaels from Ireland.

Eventually, the land was divided with the Picts in the northeast and the Scots and Gaels in the west.

William Hole, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

William Hole, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

New Beliefs

The late 6th century saw a change in Pictish religious beliefs.

While they had previously been reviled as pagans by St. Patrick, two missionaries were successful in getting the Picts to embrace Christianity: St. Ninian and St. Columba.

Theodor de Bry, Wikimedia Commons

Theodor de Bry, Wikimedia Commons

St. Ninian And St. Columba

St. Ninian is said to have converted many of the southern Picts, while St. Columba introduced Christianity to the Pictish kings.

Archaeological evidence supports the existence of monasteries associated with St. Ninian, and records of the Pictish king Bridei I confirm his Christian faith at the time of Columbo’s mission.

William Hole, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

William Hole, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Fighting Northumbria

A new kingdom had also risen from the ashes of Roman Brittania.

The Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Northumbria became a dominant power in the 7th century, stretching across northern England and parts of southern Scotland.

The Pictish kingdoms became vassals to Northumbria—until one king decided to rebel.

Oliver Dixon, Wikimedia Commons

Oliver Dixon, Wikimedia Commons

King Bridei III

Bridei mac Beli, also known as King Bridei III, was the ruler of the Pictish kingdom of Fortriu.

In 685 CE, he faced off against the Northumbrians at the Battle of Dun Nechtain. This was a decisive victory for the Picts, and secured their freedom from Northumbria.

Taking It All

About a century after defeating the Northumbrians, Fortriu had become known as the Kingdom of the Picts, and they squared off against the Kingdom of Dál Riata, which controlled the western part of Scotland and the northeast of Ireland.

The Picts won that fight, and in 793 CE, King Constantin mac Fergal made his son Domnall the king of Dál Riata.

The Arrival Of The Vikings

The Viking Age marked another turning point in Pictish history, as they found themselves fending off Viking raiders.

They also found themselves facing threats from within.

One King To Rule Them All

In 843 CE, Kenneth MacAlpin—the king of Dál Riata—rose to power by conquering the Kingdom of the Picts. From there, he united the scattered clans under a single rule, laying the foundation for what would become the Kingdom of Scotland. By the time he passed in 858 CE, MacAlpin reigned over more land than any Scottish king before him—a legacy that marked the beginning of a new era.

The End Of The Picts

The reign of Kenneth MacAlpin signaled the decline of the Picts. His descendants assimilated the Picts and by the early 870s CE, there were no mentions of the Picts in Scottish chronicles.

Under Kenneth's grandson, King Caustantín mac Áeda, there was no Dál Riata or Kingdom of the Picts.

There was only the Kingdom of Alba, which went on to become Scotland as we know it.

Jacob de Wet II, Wikimedia Commons

Jacob de Wet II, Wikimedia Commons

The Legacy Of The Picts

By the mid-12th century, the Picts had become a page in the annals of history. The people of Alba were all Gaelic Scots, and the existence of the tribal Picts became the stuff of legend.

Today, we know that the Picts were more than legends. Remnants of their existence are etched into the land—and within the blood of their modern-day descendants.