The Ground Hiding Lifetimes

Locals walked it, crops grew on it, and nobody looked twice. But once archeologists showed up, the ground started giving up secrets that had been sleeping for centuries.

It All Began In A Remote Village

It All Began In A Remote Village

Crnobuki, a quiet village in North Macedonia, unknowingly stood on the shoulders of a buried city. Hidden beneath everyday fields lay Gradishte—a site first mentioned in 1966 but long dismissed. What looked like nothing more than the countryside held ancient foundations whispering of royalty and trade.

Dean Lazarevski, Wikimedia Commons

Dean Lazarevski, Wikimedia Commons

The Ruins Were Initially Thought To Be A Roman Watchpost

Until recently, scholars wrote off Gradishte as a simple third-century BCE military checkpoint. They believed it was built during King Philip V’s reign to defend against Roman incursion. No temples, no acropolis, just tactics and towers—so they thought. Turns out, this “outpost” predates Rome’s regional influence by hundreds of years.

Few Paid Attention To What Lay Beneath The Surface

For decades, Gradishte sat idle, tossed aside in academic footnotes, and overlooked in budgets. The ground gave no hint of what lay beneath. Many walked over the shattered remains of an ancient acropolis, utterly unaware of the grand drama sleeping below.

Excavations Began In Earnest Only Fifteen Years Ago

Only in the early 2010s did real archaeological exploration kick off at Crnobuki. Teams returned with better funding and sharper questions. Those initial shovels broke through centuries of indifference. Within the decade, trenches unveiled proof that Gradishte was ancient and central—a city long buried, finally breathing again.

The Team Comprised Of Two Institutions

North Macedonia’s National Institute and Museum–Bitola and California’s Cal Poly Humboldt joined forces to crack this historical riddle. Researchers, faculty, and students combined local knowledge with international resources. What emerged was a cultural handshake, reviving a city once forgotten by both its descendants and scholars alike.

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

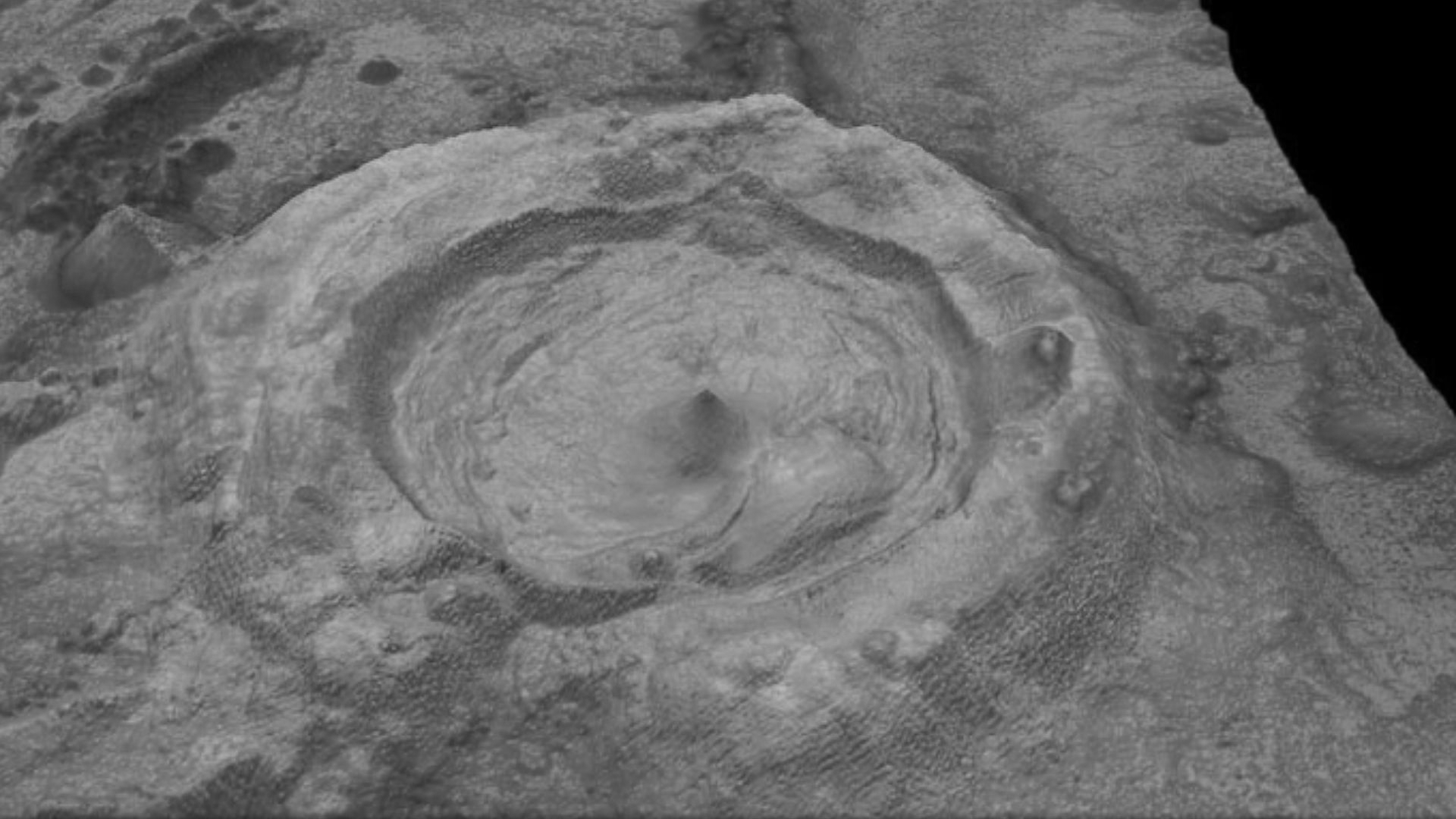

They Returned With The Latest Archaeological Technology

Ground-penetrating radar and LiDAR turned guesses into ground truth. Instead of scraping blindly, archeologists mapped everything from walls to roads in the buried architecture before touching a spade to the soil. These tools scanned 7 acres of the Acropolis beneath the village to reveal a complex cityscape.

The Charles Machine Works, Wikimedia Commons

The Charles Machine Works, Wikimedia Commons

LiDAR Aided In Plotting Ancient Borders

The LiDAR helped reveal settlement lines that the eye missed. Straight paths cut across hillsides, revealing city edges and perhaps ancient property lines. These high-tech eyes in the sky and on the ground turned archeologists into cartographers, redrawing the edges of a world thought long erased.

David Monniaux, Wikimedia Commons

David Monniaux, Wikimedia Commons

Layers Of Soil Began To Reveal A Forgotten Narrative

Each layer of excavation unearthed more than debris—it told time. From Bronze Age soil yielding stone axes to upper strata with coins and charcoal, every stratum became a timestamp. archeologists treated the site like a time tunnel, going backward through 3,000 years of evolving civilization.

Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, Wikimedia Commons

Gary Todd from Xinzheng, China, Wikimedia Commons

The Settlement Proved Far More Expansive Than Imagined

LiDAR imaging and manual digs revealed Gradishte as a 2.8-hectare city, twice as large as early estimates. This was definitely not a rest stop on history’s highway. The layout included industrial workshops, public spaces, and possibly a theater. A hidden urban heart of Upper Macedonia pulsed here.

NOAA Ocean Exploration & Research, Wikimedia Commons

NOAA Ocean Exploration & Research, Wikimedia Commons

Roads And Paths Emerged Through The Rubble

As layers of soil peeled back, patterns of worn stone paths came into view. These trails connected buildings with logical flow, suggesting a transport network for trade carts, animals, and humans. Urban arteries like these hint at high population density and organized movement across the settlement.

A Theater Was Among The First Clues

An unearthed clay theater token hinted at performances and civic gatherings, which is evidence of cultural sophistication. Entertainment, ritual, identity, and politics may have filled those stone seats. Even the structure’s alignment whispered North Macedonian design, aligning Gradishte with cities known for art and governance.

A Textile Workshop Spoke Of Economic Sophistication

They also found spindle whorls, loom weights, and dye traces that pointed to textile manufacturing. Gradishte likely produced garments for trade based on this. Imagine robes spun here, traveling to markets far across ancient trade routes. Threads woven in Crnobuki may have dressed diplomats and soldiers alike.

Peter van der Sluijs, Wikimedia Commons

Peter van der Sluijs, Wikimedia Commons

The Site May Have Welcomed Ancient Royalty And Soldiers

Gradishte’s infrastructure suggests more than farming and trade. It also had wide stone roads, gathering spaces, and civic buildings hinting at traffic from elites, perhaps even kings and generals. Could Queen Eurydice or Philip II have once walked these paths? In ancient Macedonia, royal visits were strategic.

Unknown artistUnknown artist, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown artistUnknown artist, Wikimedia Commons

A Coin Changed Everything About The Site’s Dating

In 2023, archeologists struck gold. A coin minted between 325 and 323 BCE emerged from the soil, and this was the era during Alexander the Great’s lifetime. Before this, scholars thought the city peaked under Philip V, but this single artifact rewrote the script.

How The Coin Looked Like

Minted between 325 and 323 BCE, Alexander the Great’s tetradrachms show him as Herakles on one side and Zeus seated on the other. Produced in Babylon, these coins included local mint marks and spread his authority across regions, blending political power with striking Greek iconography.

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Unknown authorUnknown author, Wikimedia Commons

Older Tools Pulled The Timeline Further Into The Past

Stone axes and ceramic shards, some dating back to 3300 BCE, added even more layers to the story. These were everyday tools from the Bronze Age. Someone must have farmed and carved these millennia before the Macedonian kings. But wait, why is the Bronze Age important?

Chris Light, Wikimedia Commons

Chris Light, Wikimedia Commons

The Bronze Age Connection Suggests Continuous Occupation

Carbon-dated bones and charcoal samples found here also revealed something stunning: this site saw life from around 360 BCE to 670 CE. That’s a historical relay race across empires, and people kept coming back. Gradishte must have been a permanent beacon in Macedonia’s shifting landscape.

Yulia Kolosova, Wikimedia Commons

Yulia Kolosova, Wikimedia Commons

The Location Is On Strategic Trade Corridors

Now, here is the thing: Gradishte didn’t arise randomly. Its location near trade routes that once linked to Constantinople made it a prime hub for merchants and maybe even marching armies. This geography explains its growth, wealth, and military relevance.

An Archeologist Wondered If This Was A Lost Capital

Nick Angeloff, with Cal Poly Humboldt, posed a provocative idea: What if this site wasn’t just a city but a capital? That thought alone flips centuries of assumptions. For a kingdom like Lyncestis, which left little behind in stone or script, Gradishte could be the missing royal puzzle piece.

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

Lyncestis Was Once A Thriving Kingdom In Upper Macedonia

Lyncestis, ruled by local dynasties, resisted absorption into larger Macedonian domains until Philip II muscled in during the fourth century BCE. Historically independent, it bordered Illyria and was a known power center. If Gradishte was Lyncus, then these ruins cradle the heart of an ancient rebel kingdom.

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, Wikimedia Commons

Lyncestis Played A Vital Role On Macedonia’s Frontiers

Frontier regions like Lyncestis weren’t just military buffers. They were cultural intersections where Greek, Illyrian, and local Macedonian customs merged. Gradishte’s art and infrastructure suggest defense, diplomacy, hybrid identity, and frontier innovation.

Marcin Konsek, Wikimedia Commons

Marcin Konsek, Wikimedia Commons

This Could Be The Birthplace Of Queen Eurydice I

Some scholars now propose that this city may have cradled a royal cradle—Queen Eurydice I, Alexander the Great’s grandmother. She was a political architect who shaped dynasties. If true, her early life at Gradishte would add feminine leadership to a story dominated by conquerors.

𝑸𝒖𝒆𝒆𝒏 𝑶𝒍𝒚𝒎𝒑𝒊𝒂𝒔 - 𝑨𝒍𝒆𝒙𝒂𝒏𝒅𝒆𝒓 𝒕𝒉𝒆 𝑮𝒓𝒆𝒂𝒕'𝒔 𝑴𝒐𝒕𝒉𝒆𝒓 by The Gorgon

𝑸𝒖𝒆𝒆𝒏 𝑶𝒍𝒚𝒎𝒑𝒊𝒂𝒔 - 𝑨𝒍𝒆𝒙𝒂𝒏𝒅𝒆𝒓 𝒕𝒉𝒆 𝑮𝒓𝒆𝒂𝒕'𝒔 𝑴𝒐𝒕𝒉𝒆𝒓 by The Gorgon

Queen Eurydice Was Alexander The Great’s Grandmother

You’ve heard of Alexander the Great, but his power lineage traces back to Eurydice. This lady managed royal alliances and tutored her descendants in statecraft. Her potential connection to this site binds Gradishte to architecture and trade, as well as to the very bloodline that conquered half the ancient world.

𝑸𝒖𝒆𝒆𝒏 𝑶𝒍𝒚𝒎𝒑𝒊𝒂𝒔 - 𝑨𝒍𝒆𝒙𝒂𝒏𝒅𝒆𝒓 𝒕𝒉𝒆 𝑮𝒓𝒆𝒂𝒕'𝒔 𝑴𝒐𝒕𝒉𝒆𝒓 by The Gorgon

𝑸𝒖𝒆𝒆𝒏 𝑶𝒍𝒚𝒎𝒑𝒊𝒂𝒔 - 𝑨𝒍𝒆𝒙𝒂𝒏𝒅𝒆𝒓 𝒕𝒉𝒆 𝑮𝒓𝒆𝒂𝒕'𝒔 𝑴𝒐𝒕𝒉𝒆𝒓 by The Gorgon

Ceramics Showed Cultural Influences Beyond Macedonia

On the same site, archeologists also found pottery pieces that displayed hybrid styles—some local, others echoing Hellenistic design. Their markings, decorations, firing techniques, and even shapes bore signs of interaction with neighboring civilizations. The people of Gradishte probably borrowed and blended the arts.

New Maps Were Drawn From The Unearthed Foundations

With every wall exposed and street traced, archeologists updated their city maps. LIDAR scans provided accurate, three-dimensional models of urban layouts. These blueprints revealed zoning and a clear urban plan; others had uncanny symmetry.